3 Futuristic Biotech Programs the U.S. Government Is Funding Right Now

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Biomedical engineer Kevin Zhao has a sensor in his arm and his chest that monitors his oxygen level in those tissues in real time.

Last month, at a conference celebrating DARPA, the research arm of the Defense Department, FBI Special Agent Edward You declared, "The 21st century will be the revolution of the life sciences."

Biomedical engineer Kevin Zhao has a sensor in his arm and chest that monitors his oxygen level in real time.

Indeed, four years ago, the agency dedicated a new office solely to advancing biotechnology. Its primary goal is to combat bioterrorism, protect U.S. forces, and promote warfighter readiness. But its research could also carry over to improve health care for the general public.

With an annual budget of about $3 billion, DARPA's employees oversee about 250 research and development programs, working with contractors from corporations, universities, and government labs to bring new technologies to life.

Check out these three current programs:

1) IMPLANTABLE SENSORS TO MEASURE OXYGEN, LACTATE, AND GLUCOSE LEVELS IN REAL TIME

Biomedical engineer Kevin Zhao has a sensor in his arm and his chest that monitors his oxygen level in those tissues in real time. With funding from DARPA for the program "In Vivo Nanoplatforms," he developed soft, flexible hydrogels that are injected just beneath the skin to perform the monitoring and that sync to a smartphone app to give the user immediate health insights.

A first-in-man trial for the glucose sensor is now underway in Europe for monitoring diabetics, according to Zhao. Volunteers eat sugary food to spike their glucose levels and prompt the monitor to register the changes.

"If this pans out, with approval from FDA, then consumers could get the sensors implanted in their core to measure their levels of glucose, oxygen, and lactate," Zhao said.

Lactate, especially, interests DARPA because it's a first responder molecule to the onset of trauma, sepsis, and potentially infection.

"The sensor could potentially detect rise of these [body chemistry numbers] and alert the user to prevent onset of dangerous illness."

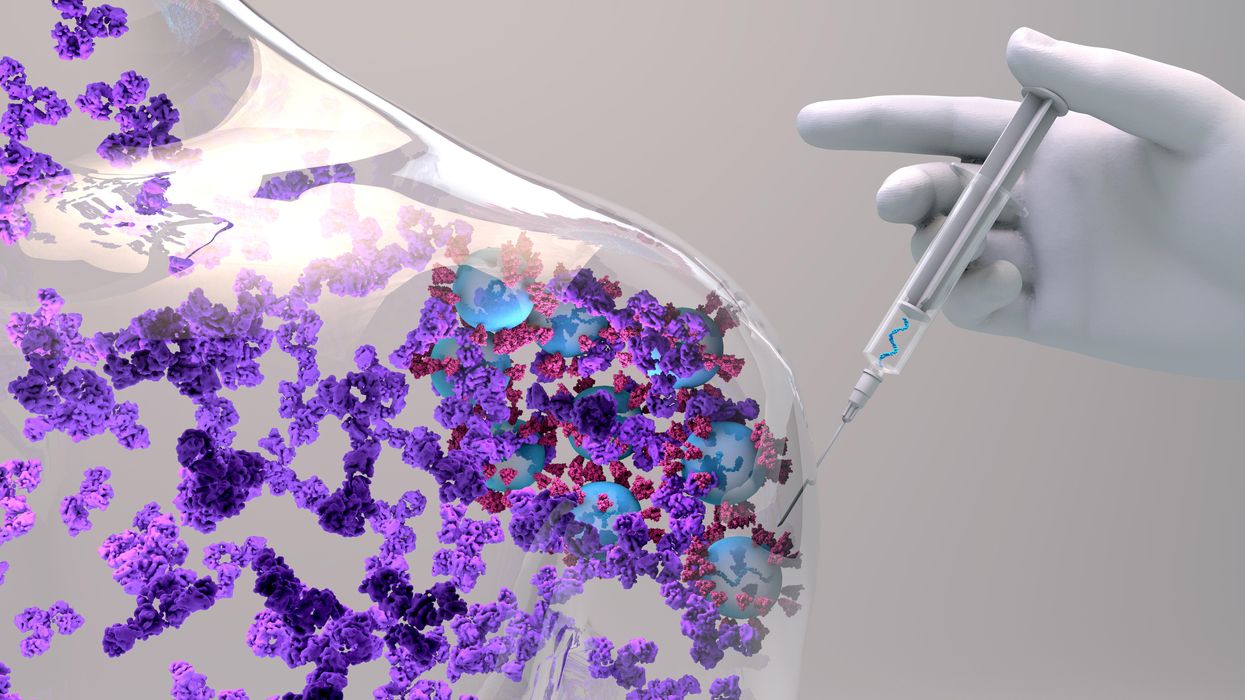

2) NEAR INSTANTANEOUS VACCINE PROTECTION DURING A PANDEMIC

Traditional vaccines can take months or years to develop, then weeks to become effective once you get it. But when an unknown virus emerges, there's no time to waste.

This program, called P3, envisions a much more ambitious approach to stop a pandemic in its tracks.

"We want to confer near instantaneous protection by doing it a different way – enlist the body as a bioreactor to produce therapeutics," said Col. Matthew Hepburn, the program manager.

So how would it work?

To fight a pandemic, we will need 20,000 doses of a vaccine in 60 days.

If you have antibodies against a certain infection, you'll be protected against that infection. This idea is to discover the genetic code for the antibody to a specific pathogen, manufacture those pieces of DNA and RNA, and then inject the code into a person's arm so the muscle cells will begin producing the required antibodies.

"The amazing thing is that it actually works, at least in animal models," said Hepburn. "The mouse muscles made enough protective antibodies so that the mice were protected."

The next step is to test the approach in humans, which the program will do over the next two years.

But the hard part is actually not discovering the genetic code for highly potent antibodies, according to Hepburn. In fact, researchers already have been able to do so in two to four weeks' time.

"The hard part is once I have an antibody, a large pharma company will say in 2 years, I can make 100-200 doses. Give us 4 years to get to 20,000 doses. That's not good enough," Hepburn said.

To fight a pandemic, we will need 20,000 doses of a vaccine in 60 days.

"We have to fundamentally change the idea that it takes a billion dollars and ten years to make a drug," he concluded. "We're going to do something radically different."

3) RAPID DIAGNOSING OF PATHOGEN EXPOSURE THROUGH EPIGENETICS

Imagine that you come down with a mysterious illness. It could be caused by a virus, bacteria, or in the most extreme catastrophe, a biological agent from a weapon of mass destruction.

What if a portable device existed that could identify--within 30 minutes—which pathogen you have been exposed to and when? It would be pretty remarkable for soldiers in the field, but also for civilians seeking medical treatment.

This is the lofty ambition of a DARPA program called Epigenetic Characterization and Observation, or ECHO.

Its success depends on a biological phenomenon known as the epigenome. While your DNA is relatively immutable, your environment can modify how your DNA is expressed, leaving marks of exposure that register within seconds to minutes; these marks can persist for decades. It's thanks to the epigenome that identical twins – who share identical DNA – can differ in health, temperament, and appearance.

These three mice are genetically identical. Epigenetic differences, however, result in vastly different observed characteristics.

Reading your epigenetic marks could theoretically reveal a time-stamped history of your body's environmental exposures.

Researchers in the ECHO program plan to create a database of signatures for exposure events, so that their envisioned device will be able to quickly scan someone's epigenome and refer to the database to sort out a diagnosis.

"One difficult part is to put a timestamp on this result, in addition to the sign of which exposure it was -- to tell us when this exposure happened," says Thomas Thomou, a contract scientist who is providing technical assistance to the ECHO program manager.

Other questions that remain up in the air for now: Do all humans have the same epigenetic response to the same exposure events? Is it possible to distinguish viral from bacterial exposures? Does dose and duration of exposure affect the signature of epigenome modification?

The program will kick off in January 2019 and is planned to last four years, as long as certain milestones of development are reached along the way. The desired prototype would be a simple device that any untrained person could operate by taking a swab or a fingerprick.

"In an outbreak," says Dr. Thomou, "it will help everyone on the ground immediately to have a rapidly deployable machine that will give you very quick answers to issues that could have far-reaching ramifications for public health safety."

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

The future of non-hormonal birth control: Antibodies can stop sperm in their tracks

Many women want non-hormonal birth control. A 22-year-old's findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

Unwanted pregnancy can now be added to the list of preventions that antibodies may be fighting in the near future. For decades, really since the 1980s, engineered monoclonal antibodies have been knocking out invading germs — preventing everything from cancer to COVID. Sperm, which have some of the same properties as germs, may be next.

Not only is there an unmet need on the market for alternatives to hormonal contraceptives, the genesis for the original research was personal for the then 22-year-old scientist who led it. Her findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

The genesis

It’s Suruchi Shrestha’s research — published in Science Translational Medicine in August 2021 and conducted as part of her dissertation while she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — that could change the future of contraception for many women worldwide. According to a Guttmacher Institute report, in the U.S. alone, there were 46 million sexually active women of reproductive age (15–49) who did not want to get pregnant in 2018. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade this year, Shrestha’s research could, indeed, be life changing for millions of American women and their families.

Now a scientist with NextVivo, Shrestha is not directly involved in the development of the contraceptive that is based on her research. But, back in 2016 when she was going through her own problems with hormonal contraceptives, she “was very personally invested” in her research project, Shrestha says. She was coping with a long list of negative effects from an implanted hormonal IUD. According to the Mayo Clinic, those can include severe pelvic pain, headaches, acute acne, breast tenderness, irregular bleeding and mood swings. After a year, she had the IUD removed, but it took another full year before all the side effects finally subsided; she also watched her sister suffer the “same tribulations” after trying a hormonal IUD, she says.

For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, Shrestha says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

Shrestha unshelved antibody research that had been sitting idle for decades. It was in the late 80s that scientists in Japan first tried to develop anti-sperm antibodies for contraceptive use. But, 35 years ago, “Antibody production had not been streamlined as it is now, so antibodies were very expensive,” Shrestha explains. So, they shifted away from birth control, opting to focus on developing antibodies for vaccines.

Over the course of the last three decades, different teams of researchers have been working to make the antibody more effective, bringing the cost down, though it’s still expensive, according to Shrestha. For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, she says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

The problem

The problem with contraceptives for women, Shrestha says, is that all but a few of them are hormone-based or have other negative side effects. In fact, some studies and reports show that millions of women risk unintended pregnancy because of medical contraindications with hormone-based contraceptives or to avoid the risks and side effects. While there are about a dozen contraceptive choices for women, there are two for men: the condom, considered 98% effective if used correctly, and vasectomy, 99% effective. Neither of these choices are hormone-based.

On the non-hormonal side for women, there is the diaphragm which is considered only 87 percent effective. It works better with the addition of spermicides — Nonoxynol-9, or N-9 — however, they are detergents; they not only kill the sperm, they also erode the vaginal epithelium. And, there’s the non-hormonal IUD which is 99% effective. However, the IUD needs to be inserted by a medical professional, and it has a number of negative side effects, including painful cramping at a higher frequency and extremely heavy or “abnormal” and unpredictable menstrual flows.

The hormonal version of the IUD, also considered 99% effective, is the one Shrestha used which caused her two years of pain. Of course, there’s the pill, which needs to be taken daily, and the birth control ring which is worn 24/7. Both cause side effects similar to the other hormonal contraceptives on the market. The ring is considered 93% effective mostly because of user error; the pill is considered 99% effective if taken correctly.

“That’s where we saw this opening or gap for women. We want a safe, non-hormonal contraceptive,” Shrestha says. Compounding the lack of good choices, is poor access to quality sex education and family planning information, according to the non-profit Urban Institute. A focus group survey suggested that the sex education women received “often lacked substance, leaving them feeling unprepared to make smart decisions about their sexual health and safety,” wrote the authors of the Urban Institute report. In fact, nearly half (45%, or 2.8 million) of the pregnancies that occur each year in the US are unintended, reports the Guttmacher Institute. Globally the numbers are similar. According to a new report by the United Nations, each year there are 121 million unintended pregnancies, worldwide.

The science

The early work on antibodies as a contraceptive had been inspired by women with infertility. It turns out that 9 to 12 percent of women who are treated for infertility have antibodies that develop naturally and work against sperm. Shrestha was encouraged that the antibodies were specific to the target — sperm — and therefore “very safe to use in women.” She aimed to make the antibodies more stable, more effective and less expensive so they could be more easily manufactured.

Since antibodies tend to stick to things that you tell them to stick to, the idea was, basically, to engineer antibodies to stick to sperm so they would stop swimming. Shrestha and her colleagues took the binding arm of an antibody that they’d isolated from an infertile woman. Then, targeting a unique surface antigen present on human sperm, they engineered a panel of antibodies with as many as six to 10 binding arms — “almost like tongs with prongs on the tongs, that bind the sperm,” explains Shrestha. “We decided to add those grabbers on top of it, behind it. So it went from having two prongs to almost 10. And the whole goal was to have so many arms binding the sperm that it clumps it” into a “dollop,” explains Shrestha, who earned a patent on her research.

Suruchi Shrestha works in the lab with a colleague. In 2016, her research on antibodies for birth control was inspired by her own experience with side effects from an implanted hormonal IUD.

UNC - Chapel Hill

The sperm stays right where it met the antibody, never reaching the egg for fertilization. Eventually, and naturally, “Our vaginal system will just flush it out,” Shrestha explains.

“She showed in her early studies that [she] definitely got the sperm immotile, so they didn't move. And that was a really promising start,” says Jasmine Edelstein, a scientist with an expertise in antibody engineering who was not involved in this research. Shrestha’s team at UNC reproduced the effect in the sheep, notes Edelstein, who works at the startup Be Biopharma. In fact, Shrestha’s anti-sperm antibodies that caused the sperm to agglutinate, or clump together, were 99.9% effective when delivered topically to the sheep’s reproductive tracts.

The future

Going forward, Shrestha thinks the ideal approach would be delivering the antibodies through a vaginal ring. “We want to use it at the source of the spark,” Shrestha says, as opposed to less direct methods, such as taking a pill. The ring would dissolve after one month, she explains, “and then you get another one.”

Engineered to have a long shelf life, the anti-sperm antibody ring could be purchased without a prescription, and women could insert it themselves, without a doctor. “That's our hope, so that it is accessible,” Shrestha says. “Anybody can just go and grab it and not worry about pregnancy or unintended pregnancy.”

Her patented research has been licensed by several biotech companies for clinical trials. A number of Shrestha’s co-authors, including her lab advisor, Sam Lai, have launched a company, Mucommune, to continue developing the contraceptives based on these antibodies.

And, results from a small clinical trial run by researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine show that a dissolvable vaginal film with antibodies was safe when tested on healthy women of reproductive age. That same group of researchers earlier this year received a $7.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health for further research on monoclonal antibody-based contraceptives, which have also been shown to block transmission of viruses, like HIV.

“As the costs come down, this becomes a more realistic option potentially for women,” says Edelstein. “The impact could be tremendous.”

The Friday Five: An mRNA vaccine works against cancer, new research suggests

In this week's Friday Five, an mRNA vaccine works against cancer for the first time. Plus, these cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power, a new theory for what causes aging, bacteria that could get you excited to work out, and a reason for sex differences in Alzheimer's.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- An mRNA vaccine that works against cancer

- These cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power

- A new theory for what causes aging

- Can bacteria make you excited to work out?

- Why women get Alzheimer's more often than men