A New Test Aims to Objectively Measure Pain. It Could Help Legitimate Sufferers Access the Meds They Need.

"That throbbing you feel for the first minute after a door slams on your finger."

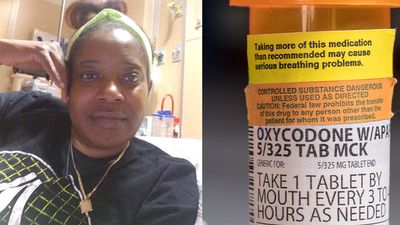

This is how Central Florida resident Bridgett Willkie describes the attacks of pain caused by her sickle cell anemia – a genetic blood disorder in which a patient's red blood cells become shaped like sickles and get stuck in blood vessels, thereby obstructing the flow of blood and oxygen.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was."

Willkie's lifelong battle with the condition has led to avascular necrosis in both of her shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. This means that her bone tissue is dying due to insufficient blood supply (sickle cell anemia is among the medical conditions that can decrease blood flow to one's bones).

"That adds to the pain significantly," she says. "Every time my heart beats, it hurts. And the pain moves. It follows the path of circulation. I liken it to a traffic jam in my veins."

For more than a decade, she received prescriptions for Oxycontin. Then, four years ago, her hematologist – who had been her doctor for 18 years – suffered a fatal heart attack. She says her longtime doctor's replacement lacked experience treating sickle cell patients and was uncomfortable writing her a prescription for opioids. What's more, this new doctor wanted to place her in a drug rehab facility.

"Because I refused to go, he stopped writing my scripts," she says. The ensuing three months were spent at home, detoxing. She describes the pain as unbearable. "Sometimes I just wanted to die."

One of the effects of the opioid epidemic is that many legitimate pain patients have seen their opioids significantly reduced or downright discontinued because of their doctors' fears of over-prescribing addictive medications.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was...Being treated like a drug-seeking patient is degrading and humiliating," says Willkie, who adds that when she is at the hospital, "it's exhausting arguing with the doctors...You dread them making their rounds because every day they come in talking about weaning you off your meds."

Situations such as these are fraught with tension between patients and doctors, who must remain wary about the risk of over-prescribing powerful and addictive medications. Adding to the complexity is that it can be very difficult to reliably assess a patient's level of physical pain.

However, this difficulty may soon decline, as Indiana University School of Medicine researchers, led by Dr. Alexander B. Niculescu, have reportedly devised a way to objectively assess physical pain by analyzing biomarkers in a patient's blood sample. The results of a study involving more than 300 participants were published earlier this year in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Niculescu – who is both a professor of psychiatry and medical neuroscience at the IU School of Medicine – explains that, when someone is in severe physical pain, a blood sample will show biomarkers related to intracellular adhesion and cell-signaling mechanisms. He adds that some of these biomarkers "have prior convergent evidence from animal or human studies for involvement in pain."

Aside from reliably measuring pain severity, Niculescu says blood biomarkers can measure the degree of one's response to treatment and also assess the risk of future recurrences of pain. He believes this new method's greatest benefit, however, might be the ability to identify a number of non-opioid medications that a particular patient is likely to respond to, based on his or her biomarker profile.

Clearly, such a method could be a gamechanger for pain patients and the professionals who treat them. As of yet, health workers have been forced to make crucial decisions based on their clinical impressions of patients; such impressions are invariably subjective. A method that enables people to prove the extent of their pain could remove the stigma that many legitimate pain patients face when seeking to obtain their needed medicine. It would also improve their chances of receiving sufficient treatment.

Niculescu says it's "theoretically possible" that there are some conditions which, despite being severe, might not reveal themselves through his testing method. But he also says that, "even if the same molecular markers that are involved in the pain process are not reflected in the blood, there are other indirect markers that should reflect the distress."

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years.

Willkie says she would welcome a reliable pain assessment method. Well-aware that she is not alone in her plight, she has more than 500 Facebook friends with sickle cell disease, and she says that "all of their opioid meds have been restricted or cut" as a result of the opioid crisis. Some now feel compelled to find their opioids "on the streets." She says she personally has never obtained opioids this way. Instead, she relies on marijuana to mitigate her pain.

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years: "It takes a while for things to translate from a lab setting to a commercial testing arena."

In the meantime, for Willkie and other patients, "we have to convince doctors and nurses that we're in pain."