Its strength is in its lack of size.

Using materials on the minuscule scale of nanometers (billionths of a meter), nanomedicines have the ability to provide treatment more precise than any other form of medicine. Under optimal circumstances, they can target specific cells and perform feats like altering the expression of proteins in tumors so that the tumors shrink.

Another appealing concept about nanomedicine is that treatment on a nano-scale, which is smaller yet than individual cells, can greatly decrease exposure to parts of the body outside the target area, thereby mitigating side effects.

But this young field's huge potential has met with an ongoing obstacle: the recipient's immune system tends to regard incoming nanomedicines as a threat and launches a complement protein attack. These complement proteins, which act together through a wave of reactions to get rid of troubling microorganisms, have had more than 500 million years to refine their craft, so they are highly effective.

Seeking to overcome a half-billion-year disadvantage, nanomaterials engineers have tried such strategies as creating so-called stealth nanoparticles.

“All new technologies face technical barriers, and it is the job of innovators to engineer solutions to them,” Brenner says.

Despite these clever attempts, nanomedicines largely keep failing to arrive at their intended destinations. According to the most comprehensive meta-analysis of nanomedicines in oncology, fewer than 1 percent of nanoparticles manage to reach their targets. The remaining 99-plus percent are expelled to the liver, spleen, or lungs – thereby squandering their therapeutic potential. Though these numbers seem discouraging, systems biologist Jacob Brenner remains undaunted. “All new technologies face technical barriers, and it is the job of innovators to engineer solutions to them,” he says.

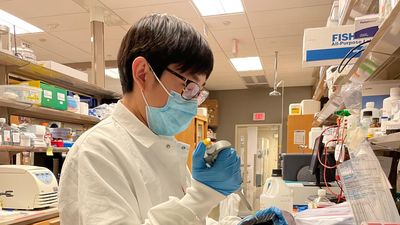

Brenner and his fellow researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have recently devised a method that, in a study published in late 2021 involving sepsis-afflicted mice, saw a longer half-life of nanoparticles in the bloodstream. This effect is crucial because “the longer our nanoparticles circulate, the more time they have to reach their target organs,” says Brenner, the study's co-principal investigator. He works as a critical care physician at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, where he also serves as an assistant professor of medicine.

The method used by Brenner's lab involves coating nanoparticles with natural suppressors that safeguard against a complement attack from the recipient's immune system. For this idea, he credits bacteria. “They are so much smarter than us,” he says.

Brenner points out that many species of bacteria have learned to coat themselves in a natural complement suppressor known as Factor H in order to protect against a complement attack.

Humans also have Factor H, along with an additional suppressor called Factor I, both of which flow through our blood. These natural suppressors “are recruited to the surface of our own cells to prevent complement [proteins] from attacking our own cells,” says Brenner.

Coating nanoparticles with a natural suppressor is a “very creative approach that can help tone and improve the activity of nanotechnology medicines inside the body,” says Avi Schroeder, an associate professor at Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, where he also serves as Head of the Targeted Drug Delivery and Personalized Medicine Group.

Schroeder explains that “being able to tone [down] the immune response to nanoparticles enhances their circulation time and improves their targeting capacity to diseased organs inside the body.” He adds how the approach taken by the Penn Med researchers “shows that tailoring the surface of the nanoparticles can help control the interactions the nanoparticles undergo in the body, allowing wider and more accurate therapeutic activity.”

Brenner says he and his research team are “working on the engineering details” to streamline the process. Such improvements could further subdue the complement protein attacks which for decades have proven the bane of nanomedical engineers.

Though these attacks have limited nanomedicine's effectiveness, the field has managed some noteworthy successes, such as the chemotherapy drugs Abraxane and Doxil, the first FDA-approved nanomedicine.

And amid the COVID-19 pandemic, nanomedicines became almost universally relevant with the vast circulation of the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, both of which consist of lipid nanoparticles. “Without the nanoparticle, the mRNA would not enter the cells effectively and would not carry out the therapeutic goal,” Schroeder explains.

These vaccines, though, are “just the start of the potential transformation that nanomedicine will bring to the world,” says Brenner. He relates how nanomedicine is “joining forces with a number of other technological innovations,” such as cell therapies in which nanoparticles aim to reprogram T-cells to attack cancer.

With a similar degree of optimism, Schroeder says, “We will see further growing impact of nanotechnologies in the clinic, mainly by enabling gene therapy for treating and even curing diseases that were incurable in the past.”

Brenner says that in the next 10 to 15 years, “nanomedicine is likely to impact patients” contending with a “huge diversity” of conditions. “I can't wait to see how it plays out.”