Anti-Aging Pioneer Aubrey de Grey: “People in Middle Age Now Have a Fair Chance”

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Aubrey de Grey at the World Stem Cell Summit in Miami on January 25, 2018.

Aging is not a mystery, says famed researcher Dr. Aubrey de Grey, perhaps the world's foremost advocate of the provocative view that medical technology will one day allow humans to control the aging process and live healthily into our hundreds—or even thousands.

"The cultural attitudes toward all of this are going to be completely turned upside down by sufficiently promising results in the lab, in mice."

He likens aging to a car wearing down over time; as the body operates normally, it accumulates damage which can be tolerated for a while, but eventually sends us into steep decline. The most promising way to escape this biological reality, he says, is to repair the damage as needed with precise scientific tools.

The bad news is that doing this groundbreaking research takes a long time and a lot of money, which has not always been readily available, in part due to a cultural phenomenon he terms "the pro-aging trance." Cultural attitudes have long been fatalistic about the inevitability of aging; many people balk at the seemingly implausible prospect of indefinite longevity.

But the good news for de Grey—and those who are cheering him on—is that his view is becoming less radical these days. Both the academic and private sectors are racing to tackle aging; his own SENS Research Foundation, for one, has spun out into five different companies. Defeating aging, he says, "is not just a future industry; it's an industry now that will be both profitable and extremely good for your health."

De Grey sat down with Editor-in-Chief Kira Peikoff at the World Stem Cell Summit in Miami to give LeapsMag the latest scoop on his work. Here is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Since your book Ending Aging was published a decade ago, scientific breakthroughs in stem cell research, genome editing, and other fields have taken the world by storm. Which of these have most affected your research?

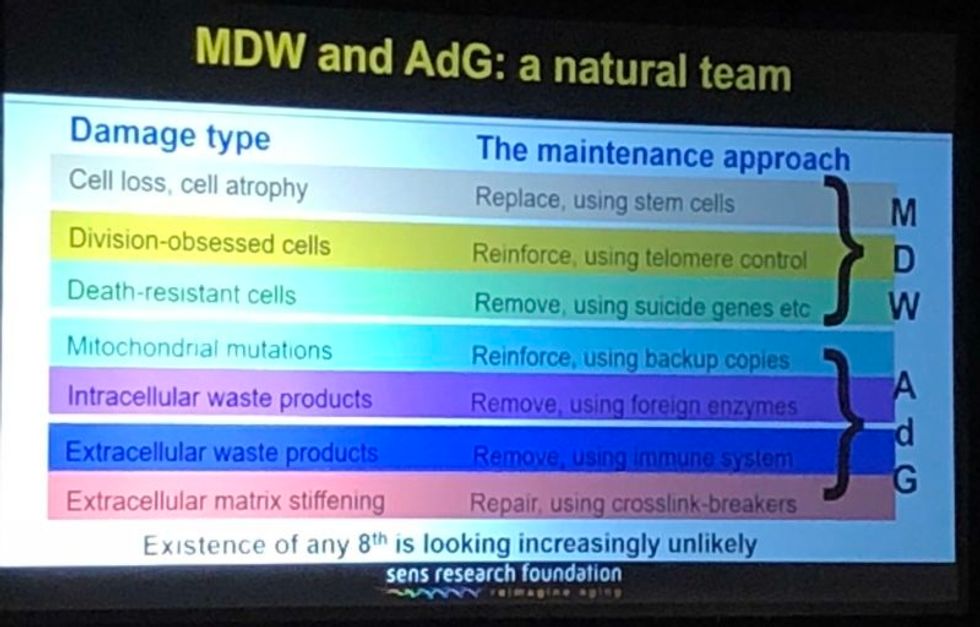

They have all affected it a lot in one way, and hardly at all in another way. They have speeded it up--facilitated short cuts, ways to get where we're already trying to go. What they have not done is identified any fundamental changes to the overall strategy. In the book, we described the seven major types of damage, and particular ways of going about fixing each of them, and that hasn't changed.

"Repair at the microscopic level, one would be able to expect to do without surgery, just by injecting the right kind of stem cells."

Has any breakthrough specifically made the biggest impact?

It's not just the obvious things, like iPS (induced pluripotent stem cells) and CRISPR (a precise tool for editing genes). It's also the more esoteric things that applied specifically to certain of our areas, but most people don't really know about them. For example, the identification of how to control something called co-translational mitochondrial protein import.

How much of the future of anti-aging treatments will involve regeneration of old tissue, or wholesale growth of new organs?

The more large-scale ones, regenerating whole new organs, are probably only going to play a role in the short-term and will be phased out relatively rapidly, simply because, in order to be useful, one has to employ surgery, which is really invasive. We'll want to try to get around that, but it seems quite likely that in the very early stages, the techniques we have for repairing things at the molecular and cellular level in situ will be insufficiently comprehensive, and so we will need to do the more sledgehammer approach of building a whole new organ and sticking it in.

Every time you are in a position where you're replacing an organ, you have the option, in principle, of repairing the organ, without replacing it. And repair at the microscopic level, one would be able to expect to do without surgery, just by injecting the right kind of stem cells or whatever. That would be something one would expect to be able to apply to someone much closer to death's door and much more safely in general, and probably much more cheaply. One would expect that subsequent generations of these therapies would move in that direction.

Your foundation is working on an initiative requiring $50 million in funding—

Well, if we had $50 million per year in funding, we could go about three times faster than we are on $5 million per year.

And you're looking at a 2021 timeframe to start human trials?

That's approximate. Remember, because we accumulate in the body so many different types of damage, that means we have many different types of therapy to repair that damage. And of course, each of those types has to be developed independently. It's very much a divide and conquer therapy. The therapies interact with each other to some extent; the repair of one type of damage may slow down the creation of another type of damage, but still that's how it's going to be.

And some of these therapies are much easier to implement than others. The easier components of what we need to do are already in clinical trials—stem cell therapies especially, and immunotherapy against amyloid in the brain, for example. Even in phase III clinical trials in some cases. So when I talk about a timeframe like 2021, or early 20s shall we say, I'm really talking about the most difficult components.

What recent strides are you most excited about?

Looking back over the past couple of years, I'm particularly proud of the successes we've had in the very most difficult areas. If you go through the 7 components of SENS, there are two that have absolutely been stuck in a rut and have gotten nowhere for 15 to 20 years, and we basically fixed that in both cases. We published two years ago in Science magazine that essentially showed a way forward against the stiffening of the extracellular matrix, which is responsible for things like wrinkles and hypertension. And then a year ago, we published a real breakthrough paper with regard to placing copies of the mitochondria DNA in the nuclear DNA modified in such a way that they still work, which is an idea that had been around for 30 years; everyone had given up on it, some a long time ago, and we basically revived it.

A slide presented by Aubrey de Grey, referencing his collaboration with Mike West at AgeX, showing the 7 types of damage that he believes must be repaired to end aging.

(Courtesy Kira Peikoff)

That's exciting. What do you think are the biggest barriers to defeating aging today: the technological challenges, the regulatory framework, the cost, or the cultural attitude of the "pro-aging" trance?

One can't really address those independently of each other. The technological side is one thing; it's hard, but we know where we're going, we've got a plan. The other ones are very intertwined with each other. A lot of people are inclined to say, the regulatory hurdle will be completely insurmountable, plus people don't recognize aging as a disease, so it's going to be a complete nonstarter. I think that's nonsense. And the reason is because the cultural attitudes toward all of this are going to be completely turned upside down before we have to worry about the regulatory hurdles. In other words, they're going to be turned upside down by sufficiently promising results in the lab, in mice. Once we get to be able to rejuvenate actually old mice really well so they live substantially longer than they otherwise would have done, in a healthy state, everyone's going to know about it and everyone's going to demand – it's not going to be possible to get re-elected unless you have a manifesto commitment to turn the FDA completely upside down and make sure this happens without any kind of regulatory obstacle.

I've been struggling away all these years trying to bring little bits of money in the door, and the reason I have is because of the skepticism as to regards whether this could actually work, combined with the pro-aging trance, which is a product of the skepticism – people not wanting to get their hopes up, so finding excuses about aging being a blessing in disguise, so they don't have to think about it. All of that will literally disintegrate pretty much overnight when we have the right kind of sufficiently impressive progress in the lab. Therefore, the availability of money will also [open up]. It's already cracking: we're already seeing the beginnings of the actual rejuvenation biotechnology industry that I've been talking about with a twinkle in my eye for some years.

"For humans, a 50-50 chance would be twenty years at this point, and there's a 10 percent chance that we won't get there for a hundred years."

Why do you think the culture is starting to shift?

There's no one thing yet. There will be that tipping point I mentioned, perhaps five years from now when we get a real breakthrough, decisive results in mice that make it simply impossible to carry on being fatalistic about all this. Prior to that, what we're already seeing is the impact of sheer old-school repeat advertising—me going out there, banging away and saying the same fucking thing again and again, and nobody saying anything that persuasively knocks me down. … And it's also the fact that we are making incremental amounts of progress, not just ourselves, but the scientific community generally. It has become incrementally more plausible that what I say might be true.

I'm sure you hate getting the timeline question, but if we're five years away from this breakthrough in mice, it's hard to resist asking—how far is that in terms of a human cure?

When I give any kind of timeframes, the only real care I have to take is to emphasize the variance. In this case I think we have got a 50-50 chance of getting to that tipping point in mice within five years from now, certainly it could be 10 or 15 years if we get unlucky. Similarly, for humans, a 50-50 chance would be twenty years at this point, and there's a 10 percent chance that we won't get there for a hundred years.

"I don't get people coming to me saying, well I don't think medicine for the elderly should be done because if it worked it would be a bad thing. People like to ignore this contradiction."

What would you tell skeptical people are the biggest benefits of a very long-lived population?

Any question about the longevity of people is the wrong question. Because the longevity that people fixate about so much will only ever occur as a side effect of health. However long ago you were born or however recently, if you're sick, you're likely to die fairly soon unless we can stop you being sick. Whereas if you're healthy, you're not. So if we do as well as we think we can do in terms of keeping people healthy and youthful however long ago they were born, then the side effect in terms of longevity and life expectancy is likely to be very large. But it's still a side effect, so the way that people actually ought to be—in fact have a requirement to be—thinking, is about whether they want people to be healthy.

Now I don't get people coming to me saying, well I don't think medicine for the elderly should be done because if it worked it would be a bad thing. People like to ignore this contradiction, they like to sweep it under the carpet and say, oh yeah, aging is totally a good thing.

People will never actually admit to the fact that what they are fundamentally saying is medicine for the elderly, if it actually works, would be bad, but still that is what they are saying.

Shifting gears a bit, I'm curious to find out which other radical visionaries in science and tech today you most admire?

Fair question. One is Mike West. I have the great privilege that I now work for him part-time with Age X. I have looked up to him very much for the past ten years, because what he did over the past 20 years starting with Geron is unimaginable today. He was working in an environment where I would not have dreamt of the possibility of getting any private money, any actual investment, in something that far out, that far ahead of its time, and he did it, again and again. It's insane what he managed to do.

What about someone like Elon Musk?

Sure, he's another one. He is totally impervious to the caution and criticism and conservatism that pervades humanity, and he's getting on making these bloody self-driving cars, space tourism, and so on, making them happen. He's thinking just the way I'm thinking really.

"You can just choose how frequently and how thoroughly you repair the damage. And you can make a different choice next time."

You famously said ten years ago that you think the first person to live to 1000 is already alive. Do you think that's still the case?

Definitely, yeah. I can't see how it could not be. Again, it's a probabilistic thing. I said there's at least a 10 percent chance that we won't get to what I call Longevity Escape Velocity for 100 years and if that's true, then the statement about 1000 years being alive already is not going to be the case. But for sure, I believe that the beneficiaries of what we may as well call SENS 1.0, the point where we get to LEV, those people are exceptionally unlikely ever to suffer from any kind of ill health correlated with their age. Because we will never fall below Longevity Escape Velocity once we attain it.

Could someone who was just born today expect—

I would say people in middle age now have a fair chance. Remember – a 50/50 chance of getting to LEV within 20 years, and when you get there, you don't just stay at biologically 70 or 80, you are rejuvenated back to biologically 30 or 40 and you stay there, so your risk of death each year is not related to how long ago you were born, it's the same as a young adult. Today, that's less than 1 in 1000 per year, and that number is going to go down as we get self-driving cars and all that, so actually 1000 is a very conservative number.

So you would be able to choose what age you wanted to go back to?

Oh sure, of course, it's just like a car. What you're doing is you're repairing damage, and the damage is still being created by the body's metabolism, so you can just choose how frequently and how thoroughly you repair the damage. And you can make a different choice next time.

What would be your perfect age?

I have no idea. That's something I don't have an opinion about, because I could change it whenever I like.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Important findings are starting to emerge from research on how genes shape the human response to the Covid virus.

From infections with no symptoms to why men are more likely to be hospitalized in the ICU and die of COVID-19, new research shows that your genes play a significant role

Early in the pandemic, genetic research focused on the virus because it was readily available. Plus, the virus contains only 30,000 bases in a dozen functional genes, so it's relatively easy and affordable to sequence. Additionally, the rapid mutation of the virus and its ability to escape antibody control fueled waves of different variants and provided a reason to follow viral genetics.

In comparison, there are many more genes of the human immune system and cellular functions that affect viral replication, with about 3.2 billion base pairs. Human studies require samples from large numbers of people, the analysis of each sample is vastly more complex, and sophisticated computer analysis often is required to make sense of the raw data. All of this takes time and large amounts of money, but important findings are beginning to emerge.

Asymptomatics

About half the people exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease, never develop symptoms of this disease, or their symptoms are so mild they often go unnoticed. One piece of understanding the phenomena came when researchers showed that exposure to OC43, a common coronavirus that results in symptoms of a cold, generates immune system T cells that also help protect against SARS-CoV-2.

Jill Hollenbach, an immunologist at the University of California at San Francisco, sought to identify the gene behind that immune protection. Most COVID-19 genetic studies are done with the most seriously ill patients because they are hospitalized and thus available. “But 99 percent of people who get it will never see the inside of a hospital for COVID-19,” she says. “They are home, they are not interacting with the health care system.”

Early in the pandemic, when most labs were shut down, she tapped into the National Bone Marrow Donor Program database. It contains detailed information on donor human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), key genes in the immune system that must match up between donor and recipient for successful transplants of marrow or organs. Each HLA can contain alleles, slight molecular differences in the DNA of the HLA, which can affect its function. Potential HLA combinations can number in the tens of thousands across the world, says Hollenbach, but each person has a smaller number of those possible variants.

She teamed up with the COVID-19 Citizen Science Study a smartphone-based study to track COVID-19 symptoms and outcomes, to ask persons in the bone marrow donor registry about COVID-19. The study enlisted more than 30,000 volunteers. Those volunteers already had their HLAs annotated by the registry, and 1,428 tested positive for the virus.

Analyzing five key HLAs, she found an allele in the gene HLA-B*15:01 that was significantly overrepresented in people who didn’t have any symptoms. The effect was even stronger if a person had inherited the allele from both parents; these persons were “more than eight times more likely to remain asymptomatic than persons who did not carry the genetic variant,” she says. Altogether this HLA was present in about 10 percent of the general European population but double that percentage in the asymptomatic group. Hollenbach and her colleagues were able confirm this in other different groups of patients.

What made the allele so potent against SARS-CoV-2? Part of the answer came from x-ray crystallography. A key element was the molecular shape of parts of the cold virus OC43 and SARS-CoV-2. They were virtually identical, and the allele could bind very tightly to them, present their molecular antigens to T cells, and generate an extremely potent T cell response to the viruses. And “for whatever reasons that generated a lot of memory T cells that are going to stick around for a long time,” says Hollenbach. “This T cell response is very early in infection and ramps up very quickly, even before the antibody response.”

Understanding the genetics of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is important because it provides clues into the conditions of T cells and antigens that support a response without any symptoms, she says. “It gives us an opportunity to think about whether this might be a vaccine design strategy.”

Dead men

A researcher at the Leibniz Institute of Virology in Hamburg Germany, Guelsah Gabriel, was drawn to a question at the other end of the COVID-19 spectrum: why men more likely to be hospitalized and die from the infection. It wasn't that men were any more likely to be exposed to the virus but more likely, how their immune system reacted to it

Several studies had noted that testosterone levels were significantly lower in men hospitalized with COVID-19. And, in general, the lower the testosterone, the worse the prognosis. A year after recovery, about 30 percent of men still had lower than normal levels of testosterone, a condition known as hypogonadism. Most of the men also had elevated levels of estradiol, a female hormone (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34402750/).

Every cell has a sex, expressing receptors for male and female hormones on their surface. Hormones docking with these receptors affect the cells' internal function and the signals they send to other cells. The number and role of these receptors varies from tissue to tissue.

Gabriel began her search by examining whole exome sequences, the protein-coding part of the genome, for key enzymes involved in the metabolism of sex hormones. The research team quickly zeroed in on CYP19A1, an enzyme that converts testosterone to estradiol. The gene that produces this enzyme has a number of different alleles, the molecular variants that affect the enzyme's rate of metabolizing the sex hormones. One genetic variant, CYP19A1 (Thr201Met), is typically found in 6.2 percent of all people, both men and women, but remarkably, they found it in 68.7 percent of men who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

Lung surprise

Lungs are the tissue most affected in COVID-19 disease. Gabriel wondered if the virus might be affecting expression of their target gene in the lung so that it produces more of the enzyme that converts testosterone to estradiol. Studying cells in a petri dish, they saw no change in gene expression when they infected cells of lung tissue with influenza and the original SARS-CoV viruses that caused the SARS outbreak in 2002. But exposure to SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, increased gene expression up to 40-fold, Gabriel says.

Did the same thing happen in humans? Autopsy examination of patients in three different cites found that “CYP19A1 was abundantly expressed in the lungs of COVID-19 males but not those who died of other respiratory infections,” says Gabriel. This increased enzyme production led likely to higher levels of estradiol in the lungs of men, which “is highly inflammatory, damages the tissue, and can result in fibrosis or scarring that inhibits lung function and repair long after the virus itself has disappeared.” Somehow the virus had acquired the capacity to upregulate expression of CYP19A1.

Only two COVID-19 positive females showed increased expression of this gene. The menopause status of these women, or whether they were on hormone replacement therapy was not known. That could be important because female hormones have a protective effect for cardiovascular disease, which women often lose after going through menopause, especially if they don’t start hormone replacement therapy. That sex-specific protection might also extend to COVID-19 and merits further study.

The team was able to confirm their findings in golden hamsters, the animal model of choice for studying COVID-19. Testosterone levels in male animals dropped 5-fold three days after infection and began to recover as viral levels declined. CYP19A1 transcription increased up to 15-fold in the lungs of the male but not the females. The study authors wrote, “Virus replication in the male lungs was negatively associated with testosterone levels.”

The medical community studying COVID-19 has slowly come to recognize the importance of adipose tissue, or fat cells. They are known to express abundant levels of CYP19A1 and play a significant role as metabolic tissue in COVID-19. Gabriel adds, “One of the key findings of our study is that upon SARS-CoV-2 infection, the lung suddenly turns into a metabolic organ by highly expressing” CYP19A1.

She also found evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can infect the gonads of hamsters, thereby likely depressing circulating levels of sex hormones. The researchers did not have autopsy samples to confirm this in humans, but others have shown that the virus can replicate in those tissues.

A possible treatment

Back in the lab, substituting low and high doses of testosterone in SARS-COV-2 infected male hamsters had opposite effects depending on testosterone dosage used. Gabriel says that hormone levels can vary so much, depending on health status and age and even may change throughout the day, that “it probably is much better to inhibit the enzyme” produced by CYP19A1 than try to balance the hormones.

Results were better with letrozole, a drug approved to treat hypogonadism in males, which reduces estradiol levels. The drug also showed benefit in male hamsters in terms of less severe disease and faster recovery. She says more details need to be worked out in using letrozole to treat COVID-19, but they are talking with hospitals about clinical trials of the drug.

Gabriel has proposed a four hit explanation of how COVID-19 can be so deadly for men: the metabolic quartet. First is the genetic risk factor of CYP19A1 (Thr201Met), then comes SARS-CoV-2 infection that induces even greater expression of this gene and the deleterious increase of estradiol in the lung. Age-related hypogonadism and the heightened inflammation of obesity, known to affect CYP19A1 activity, are contributing factors in this deadly perfect storm of events.

Studying host genetics, says Gabriel, can reveal new mechanisms that yield promising avenues for further study. It’s also uniting different fields of science into a new, collaborative approach they’re calling “infection endocrinology,” she says.

New device finds breast cancer like earthquake detection

Jessica Fitzjohn, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Canterbury, demonstrates the novel breast cancer screening device.

Mammograms are necessary breast cancer checks for women as they reach the recommended screening age between 40 and 50 years. Yet, many find the procedure uncomfortable. “I have large breasts, and to be able to image the full breast, the radiographer had to manipulate my breast within the machine, which took time and was quite uncomfortable,” recalls Angela, who preferred not to disclose her last name.

Breast cancer is the most widespread cancer in the world, affecting 2.3 million women in 2020. Screening exams such as mammograms can help find breast cancer early, leading to timely diagnosis and treatment. If this type of cancer is detected before the disease has spread, the 5-year survival rate is 99 percent. But some women forgo mammograms due to concerns about radiation or painful compression of breasts. Other issues, such as low income and a lack of access to healthcare, can also serve as barriers, especially for underserved populations.

Researchers at the University of Canterbury and startup Tiro Medical in Christchurch, New Zealand are hoping their new device—which doesn’t involve any radiation or compression of the breasts—could increase the accuracy of breast cancer screening, broaden access and encourage more women to get checked. They’re digging into clues from the way buildings move in an earthquake to help detect more cases of this disease.

Earthquake engineering inspires new breast cancer screening tech

What’s underneath a surface affects how it vibrates. Earthquake engineers look at the vibrations of swaying buildings to identify the underlying soil and tissue properties. “As the vibration wave travels, it reflects the stiffness of the material between that wave and the surface,” says Geoff Chase, professor of engineering at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Chase is applying this same concept to breasts. Analyzing the surface motion of the breast as it vibrates could reveal the stiffness of the tissues underneath. Regions of high stiffness could point to cancer, given that cancerous breast tissue can be up to 20 times stiffer than normal tissue. “If in essence every woman’s breast is soft soil, then if you have some granite rocks in there, we’re going to see that on the surface,” explains Chase.

The earthquake-inspired device exceeds the 87 percent sensitivity of a 3D mammogram.

That notion underpins a new breast screening device, the brainchild of Chase. Women lie face down, with their breast being screened inside a circular hole and the nipple resting on a small disc called an actuator. The actuator moves up and down, between one and two millimeters, so there’s a small vibration, “almost like having your phone vibrate on your nipple,” says Jessica Fitzjohn, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Canterbury who collaborated on the device design with Chase.

Cameras surrounding the device take photos of the breast surface motion as it vibrates. The photos are fed into image processing algorithms that convert them into data points. Then, diagnostic algorithms analyze those data points to find any differences in the breast tissue. “We’re looking for that stiffness contrast which could indicate a tumor,” Fitzjohn says.

A nascent yet promising technology

The device has been tested in a clinical trial of 14 women: one with healthy breasts and 13 with a tumor in one breast. The cohort was small but diverse, varying in age, breast volume and tumor size.

Results from the trial yielded a sensitivity rate, or the likelihood of correctly detecting breast cancer, of 85 percent. Meanwhile, the device’s specificity rate, or the probability of diagnosing healthy breasts, was 77 percent. By combining and optimizing certain diagnostic algorithms, the device reached between 92 and 100 percent sensitivity and between 80 and 86 percent specificity, which is comparable to the latest 3D mammogram technology. Called tomosynthesis, these 3D mammograms take a number of sharper, clearer and more detailed 3D images compared to the single 2D image of a conventional mammogram, and have a specificity score of 92 percent. Although the earthquake-inspired device’s specificity is lower, it exceeds the 87 percent sensitivity of a 3D mammogram.

The team hopes that cameras with better resolution can help improve the numbers. And with a limited amount of data in the first trial, the researchers are looking into funding for another clinical trial to validate their results on a larger cohort size.

Additionally, during the trial, the device correctly identified one woman’s breast as healthy, while her prior mammogram gave a false positive. The device correctly identified it as being healthy tissue. It was also able to capture the tiniest tumor at 7 millimeters—around a third of an inch or half as long as an aspirin tablet.

Diagnostic findings from the device are immediate.

When using the earthquake-inspired device, women lie face down, with their breast being screened inside circular holes.

University of Canterbury.

But more testing is needed to “prove the device’s ability to pick up small breast cancers less than 10 to 15 millimeters in size, as we know that finding cancers when they are small is the best way of improving outcomes,” says Richard Annand, a radiologist at Pacific Radiology in New Zealand. He explains that mammography already detects most precancerous lesions, so if the device will only be able to find large masses or lumps it won’t be particularly useful. While not directly involved in administering the clinical trial for the device, Annand was a director at the time for Canterbury Breastcare, where the trial occurred.

Meanwhile, Monique Gary, a breast surgical oncologist and medical director of the Grand View Health Cancer program in Pennsylvania, U.S., is excited to see new technologies advancing breast cancer screening and early detection. But she notes that the device may be challenging for “patients who are unable to lay prone, such as pregnant women as well as those who are differently abled, and this machine might exclude them.” She adds that it would also be interesting to explore how breast implants would impact the device’s vibrational frequency.

Diagnostic findings from the device are immediate, with the results available “before you put your clothes back on,” Chase says. The absence of any radiation is another benefit, though Annand considers it a minor edge “as we know the radiation dose used in mammography is minimal, and the advantages of having a mammogram far outweigh the potential risk of radiation.”

The researchers also conducted a separate ergonomic trial with 40 women to assess the device’s comfort, safety and ease of use. Angela was part of that trial and described the experience as “easy, quick, painless and required no manual intervention from an operator.” And if a person is uncomfortable being topless or having their breasts touched by someone else, “this type of device would make them more comfortable and less exposed,” she says.

While mammograms remain “the ‘gold standard’ in breast imaging, particularly screening, physicians need an option that can be used in combination with mammography.

Fitzjohn acknowledges that “at the moment, it’s quite a crude prototype—it’s just a block that you lie on.” The team prioritized function over form initially, but they’re now planning a few design improvements, including more cushioning for the breasts and the surface where the women lie on.

While mammograms remains “the ‘gold standard’ in breast imaging, particularly screening, physicians need an option that is good at excluding breast cancer when used in combination with mammography, has good availability, is easy to use and is affordable. There is the possibility that the device could fill this role,” Annand says.

Indeed, the researchers envision their new breast screening device as complementary to mammograms—a prescreening tool that could make breast cancer checks widely available. As the device is portable and doesn’t require specialized knowledge to operate, it can be used in clinics, pop-up screening facilities and rural communities. “If it was easily accessible, particularly as part of a checkup with a [general practitioner] or done in a practice the patient is familiar with, it may encourage more women to access this service,” Angela says. For those who find regular mammograms uncomfortable or can’t afford them, the earthquake-inspired device may be an option—and an even better one.

Broadening access could prompt more women to go for screenings, particularly younger women at higher risk of getting breast cancer because of a family history of the disease or specific gene mutations. “If we can provide an option for them then we can catch those cancers earlier,” Fitzjohn syas. “By taking screening to people, we’re increasing patient-centric care.”

With the team aiming to lower the device’s cost to somewhere between five and eight times less than mammography equipment, it would also be valuable for low-to-middle-income nations that are challenged to afford the infrastructure for mammograms or may not have enough skilled radiologists.

For Fitzjohn, the ultimate goal is to “increase equity in breast screening and catch cancer early so we have better outcomes for women who are diagnosed with breast cancer.”