Antibody Testing Alone is Not the Key to Re-Opening Society

Immunity tests have too many unknowns right now to make them very useful in determining protective antibody status.

[Editor's Note: We asked experts from different specialties to weigh in on a timely Big Question: "How should immunity testing play a role in re-opening society?" Below, a virologist offers her perspective.]

With the advent of serology testing and increased emphasis on "re-opening" America, public health officials have begun considering whether or not people who have recovered from COVID-19 can safely re-enter the workplace.

"Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known."

Conventional wisdom holds that people who have developed antibodies in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, are likely to be immune to reinfection.

For most acute viral infections, this is generally true. However, SARS-CoV-2 is a new pathogen, and there are currently many unanswered questions about immunity. Can recovered patients be reinfected or transmit the virus? Does symptom severity determine how protective responses will be after recovery? How long will protection last? Understanding these basic features is essential to phased re-opening of the government and economy for people who have recovered from COVID-19.

One mechanism that has been considered is issuing "immunity certificates" to individuals with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. These certificates would verify that individuals have already recovered from COVID-19, and thus have antibodies in their blood that will protect them against reinfection, enabling them to safely return to work and participate in society. Although this sounds reasonable in theory, there are many practical reasons why this is not a wise policy decision to ease off restrictive stay-home orders and distancing practices.

Too Many Scientific Unknowns

Serology tests measure antibodies in the serum—the liquid component of blood, which is where the antibodies are located. In this case, serology tests measure antibodies that specifically bind to SARS-CoV-2 virus particles. Usually when a person is infected with a virus, they develop antibodies that can "recognize" that virus, so the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies indicates that a person has been previously exposed to the virus. Broad serology testing is critical to knowing how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, since testing capacity for the virus itself has been so low.

Tests for the virus measure amounts of SARS-CoV-2 RNA—the virus's genetic material—directly, and thus will not detect the virus once a person has recovered. Thus, the majority of people who were not severely ill and did not require hospitalization, or did not have direct contact with a confirmed case, will not test positive for the virus weeks after they have recovered and can only determine if they had COVID-19 by testing for antibodies.

In most cases, for most pathogens, antibodies are also neutralizing, meaning they bind to the virus and render it incapable of infecting cells, and this protects against future infections. Immunity certificates are based on the assumption that people with antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 will be protected against reinfection. The problem is that we've only known that SARS-CoV-2 existed for a little over four months. Although studies so far indicate that most (but not all) patients with confirmed COVID-19 cases develop antibodies, we don't know the extent to which antibodies are protective against reinfection, or how long that protection will last. Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known.

The limited data so far is encouraging with regard to protective immunity. Most of the patient sera tested for antibodies show reasonable titers of IgG, the type of antibodies most likely to be neutralizing. Furthermore, studies have shown that these IgG antibodies are capable of neutralizing surrogate viruses as well as infectious SARS-CoV-2 in laboratory tests. In addition, rhesus monkeys that were experimentally infected with SARS-CoV-2 and allowed to recover were protected from reinfection after a subsequent experimental challenge. These data tentatively suggest that most people are likely to develop neutralizing IgG, and protective immunity, after being infected by SARS-CoV-2.

However, not all COVID-19 patients do produce high levels of antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2. A small number of patients in one study had no detectable neutralizing IgG. There have also been reports of patients in South Korea testing PCR positive after a prior negative test, indicating reinfection or reactivation. These cases may be explained by the sensitivity of the PCR test, and no data have been produced to indicate that these cases are genuine reinfection or recurrence of viral infection.

Complicating matters further, not all serology tests measure antibody titers. Some rapid serology tests are designed to be binary—the test can either detect antibodies or not, but does not give information about the amount of antibodies circulating. Based on our current knowledge, we cannot be certain that merely having any level of detectable antibodies alone guarantees protection from reinfection, or from a subclinical reinfection that might not cause a second case of COVID-19, but could still result in transmission to others. These unknowns remain problematic even with tests that accurately detect the presence of antibodies—which is not a given today, as many of the newly available tests are reportedly unreliable.

A Logistical and Ethical Quagmire

While most people are eager to cast off the isolation of physical distancing and resume their normal lives, mere desire to return to normality is not an indicator of whether those antibodies actually work, and no certificate can confer immune protection. Furthermore, immunity certificates could lead to some complicated logistical and ethical issues. If antibodies do not guarantee protective immunity, certifying that they do could give antibody-positive people a false sense of security, causing them to relax infection control practices such as distancing and hand hygiene.

"We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper."

Certificates could be forged, putting susceptible people at higher exposure risk. It's not clear who would issue them, what they would entitle the bearer to do or not do, or how certification would be verified or enforced. There are many ways in which such certificates could be used as a pretext to discriminate against people based on health status, in addition to disability, race, and socioeconomic status. Tracking people based on immune status raises further concerns about privacy and civil rights.

Rather than issuing documents confirming immune status, we should instead "re-open" society cautiously, with widespread virus and serology testing to accurately identify and isolate infected cases rapidly, with immediate contact tracing to safely quarantine and monitor those at exposure risk. Broad serosurveillance must be coupled with functional assays for neutralization activity to begin assessing how protective antibodies might actually be against SARS-CoV-2 infection. To understand how long immunity lasts, we should study antibodies, as well as the functional capabilities of other components of the larger immune system, such as T cells, in recovered COVID-19 patients over time.

We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper. Re-opening society, the government, and the economy depends not only on accurately determining how many people have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, but on a deeper understanding of how those antibodies work to provide protection.

A Rare Disease Just "Messed with the Wrong Mother." Now She's Fighting to Beat It Once and For All.

Amber Freed and Maxwell near their home in Denver, Colorado.

Amber Freed felt she was the happiest mother on earth when she gave birth to twins in March 2017. But that euphoric feeling began to fade over the next few months, as she realized her son wasn't making the same developmental milestones as his sister. "I had a perfect benchmark because they were twins, and I saw that Maxwell was floppy—he didn't have muscle tone and couldn't hold his neck up," she recalls. At first doctors placated her with statements that boys sometimes develop slower than girls, but the difference was just too drastic. At 10 month old, Maxwell had never reached to grab a toy. In fact, he had never even used his hands.

Thinking that perhaps Maxwell couldn't see well, Freed took him to an ophthalmologist who was the first to confirm her worst fears. He didn't find Maxwell to have vision problems, but he thought there was something wrong with the boy's brain. He had seen similar cases before and they always turned out to be rare disorders, and always fatal. "Start preparing yourself for your child not to live," he had said.

Getting the diagnosis took months of painful, invasive procedures, as well as fighting with the health insurance to get the genetic testing approved. Finally, in June 2018, doctors at the Children's Hospital Colorado gave the Freeds their son's diagnosis—a genetic mutation so rare it didn't even have a name, just a bunch of letters jammed together into a word SLC6A1—same as the name of the mutated gene. The mutation, with only 40 cases known worldwide at the time, caused developmental disabilities, movement and speech disorders, and a debilitating form of epilepsy.

The doctors didn't know much about the disorder, but they said that Maxwell would also regress in his development when he turned three or four. They couldn't tell how long he would live. "Hopefully you would become an expert and educate us about it," they said, as they gave Freed a five-page paper on the SLC6A1 and told her to start calling scientists if she wanted to help her son in any way. When she Googled the name, nothing came up. She felt horrified. "Our disease was too rare to care."

Freed's husband, a 6'2'' college football player broke down in sobs and she realized that if anything could be done to help Maxwell, she'd have be the one to do it. "I understood that I had to fight like a mother," she says. "And a determined mother can do a lot of things."

The Freed family.

Courtesy Amber Freed

She quit her job as an equity analyst the day of the diagnosis and became a full-time SLC6A1 citizen scientist looking for researchers studying mutations of this gene. In the wee hours of the morning, she called scientists in Europe. As the day progressed, she called researchers on the East Coast, followed by the West in the afternoon. In the evening, she switched to Asia and Australia. She asked them the same question. "Can you help explain my gene and how do we fix it?"

Scientists need money to do research, so Freed launched Milestones for Maxwell fundraising campaign, and a SLC6A1 Connect patient advocacy nonprofit, dedicated to improving the lives of children and families battling this rare condition. And then it became clear that the mutation wasn't as rare as it seemed. As other parents began to discover her nonprofit, the number of known cases rose from 40 to 100, and later to 400, Freed says. "The disease is only rare until it messes with the wrong mother."

It took one mother to find another to start looking into what's happening inside Maxwell's brain. Freed came across Jeanne Paz, a Gladstone Institutes researcher who studies epilepsy with particular interest in absence or silent seizures—those that don't manifest by convulsions, but rather make patients absently stare into space—and that's one type of seizures Maxwell has. "It's like a brief period of silence in the brain during which the person doesn't pay attention to what's happening, and as soon as they come out of the seizure they are back to life," Paz explains. "It's like a pause button on consciousness." She was working to understand the underlying biology.

To understand how seizures begin, spread and stop, Paz uses optogenetics in mice. From words "genetic" and "optikós," which means visible in Greek, the optogenetics technique involves two steps. First, scientists introduce a light-sensitive gene into a specific brain cell type—for example into excitatory neurons that release glutamate, a neurotransmitter, which activates other cells in the brain. Then they implant a very thin optical fiber into the brain area where they forged these light-sensitive neurons. As they shine the light through the optical fiber, researchers can make excitatory neurons to release glutamate—or instead tell them to stop being active and "shut up". The ability to control what these neurons of interest do, quite literally sheds light onto where seizures start, how they propagate and what cells are involved in stopping them.

"Let's say a seizure started and we shine the light that reduces the activity of specific neurons," Paz explains. "If that stops the seizure, we know that activating those cells was necessary to maintain the seizure." Likewise, shutting down their activity will make the seizure stop.

Freed reached out to Paz in 2019 and the two women had an instant connection. They were both passionate about brain and seizures research, even if for different reasons. Freed asked Paz if she would study her son's seizures and Paz agreed.

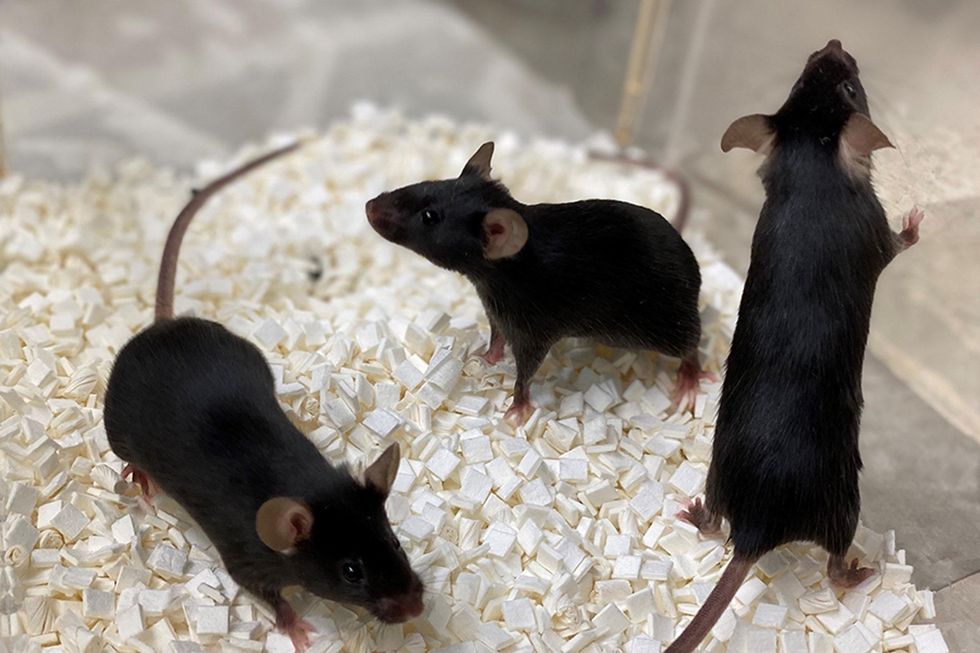

To do that, Paz needed mice that carried the SLC6A1 mutation, so Freed found a company in China that created them to specs. The company replaced a mouse SLC6A1 gene with a human mutated one and shipped them over to Paz's lab. "We call them Maxwell mice," Paz says, "and we are now implanting electrodes into them to see which brain regions generate seizures." That would help them understand what goes wrong and what brain cells are malfunctioning in the SLC6A1 mice—and help scientists better understand what might cause seizures in children.

Bred to carry SLC6A1 mutation, these "Maxwell mice" will help better understand this debilitating genetic disease. (These mice are from Vanderbilt University, where researchers are also studying SLC6A1.)

Courtesy Amber Freed

This information—along with other research Amber is funding in other institutions—will inform the development of a novel genetic treatment, in which scientists would deploy a harmless virus to deliver a healthy, working copy of the SLC6A1 gene into the mice brains. They would likely deliver the therapeutic via a spinal tap infusion, and if it works and doesn't produce side effects in mice, the human trials will follow.

In the meantime, Freed is raising money to fund other research of various stop-gap measures. On April 22, 2021, she updated her Milestone for Maxwell page with a post that her nonprofit is funding yet another effort. It is a trial at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, in which doctors will use an already FDA-approved drug, which was recently repurposed for the SLC6A1 condition to treat epilepsy in these children. "It will buy us time," Freed says—while the gene therapy effort progresses.

Freed is determined to beat SLC6A1 before it beats down her family. She hopes to put an end to this disease—and similar genetic diseases—once and for all. Her goal is not only to have scientists create a remedy, but also to add the mutation to a newborn screening panel. That way, children born with this condition in the future would receive gene therapy before they even leave the hospital.

"I don't want there to be another Maxwell Freed," she says, "and that's why I am fighting like a mother." The gene therapy trial still might be a few years away, but the Weill Cornell one aims to launch very soon—possibly around Mother's Day. This is yet another milestone for Maxwell, another baby step forward—and the best gift a mother can get.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

On May 13th, scientific and medical experts will discuss and answer questions about the vaccine for those under 16.

This virtual event convened leading scientific and medical experts to address the public's questions and concerns about Covid-19 vaccines in kids and teens. Highlight video below.

DATE:

Thursday, May 13th, 2021

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. EDT

Dr. H. Dele Davies, M.D., MHCM

Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Dean for Graduate Studies at the University of Nebraska Medical (UNMC). He is an internationally recognized expert in pediatric infectious diseases and a leader in community health.

Dr. Emily Oster, Ph.D.

Professor of Economics at Brown University. She is a best-selling author and parenting guru who has pioneered a method of assessing school safety.

Dr. Tina Q. Tan, M.D.

Professor of Pediatrics at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. She has been involved in several vaccine survey studies that examine the awareness, acceptance, barriers and utilization of recommended preventative vaccines.

Dr. Inci Yildirim, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc.

Associate Professor of Pediatrics (Infectious Disease); Medical Director, Transplant Infectious Diseases at Yale School of Medicine; Associate Professor of Global Health, Yale Institute for Global Health. She is an investigator for the multi-institutional COVID-19 Prevention Network's (CoVPN) Moderna mRNA-1273 clinical trial for children 6 months to 12 years of age.

About the Event Series

This event is the second of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.