Scientists fight to avoid a perfect storm of fungal infections

Doctors worry that fungal pathogens may cause the next pandemic.

Bacterial antibiotic resistance has been a concern in the medical field for several years. Now a new, similar threat is arising: drug-resistant fungal infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers antifungal and antimicrobial resistance to be among the world’s greatest public health challenges.

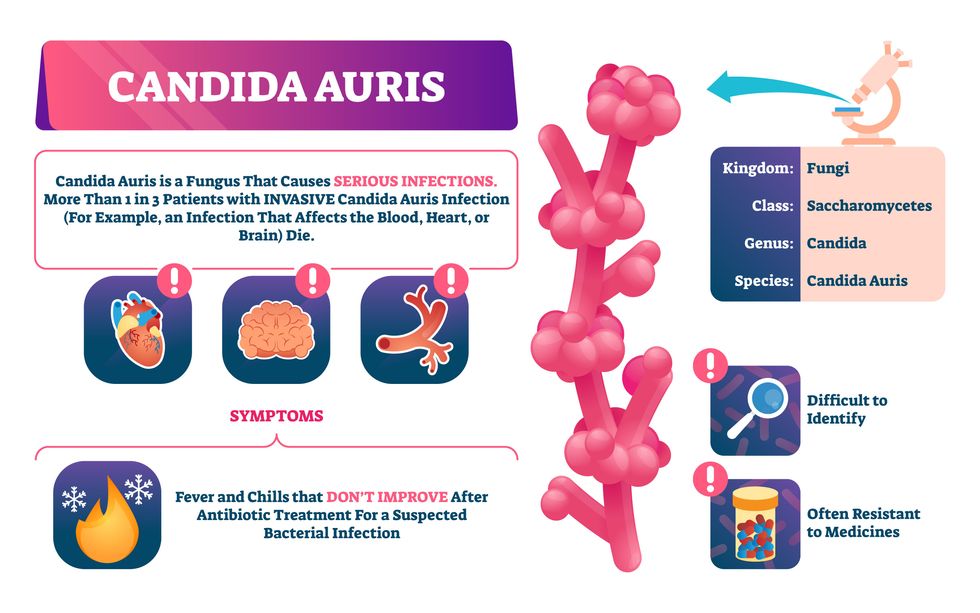

One particular type of fungal infection caused by Candida auris is escalating rapidly throughout the world. And to make matters worse, C. auris is becoming increasingly resistant to current antifungal medications, which means that if you develop a C. auris infection, the drugs your doctor prescribes may not work. “We’re effectively out of medicines,” says Thomas Walsh, founding director of the Center for Innovative Therapeutics and Diagnostics, a translational research center dedicated to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem. Walsh spoke about the challenges at a Demy-Colton Virtual Salon, one in a series of interactive discussions among life science thought leaders.

Although C. auris typically doesn’t sicken healthy people, it afflicts immunocompromised hospital patients and may cause severe infections that can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which the overwhelmed immune system begins to attack the body’s own organs. Between 30 and 60 percent of patients who contract a C. auris infection die from it, according to the CDC. People who are undergoing stem cell transplants, have catheters or have taken antifungal or antibiotic medicines are at highest risk. “We’re coming to a perfect storm of increasing resistance rates, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed patients worldwide and a bug that is adapting to higher temperatures as the climate changes,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the National BioDefense Science Board.

Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures.

Although medical professionals aren’t concerned at this point about C. auris evolving to affect healthy people, they worry that its presence in hospitals can turn routine surgeries into life-threatening calamities. “It’s coming,” says Fernandes. “It’s just a matter of time.”

An emerging global threat

“Fungi are found in the environment,” explains Fernandes, so Candida spores can easily wind up on people’s skin. In hospitals, they can be transferred from contact with healthcare workers or contaminated surfaces. Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures. It can enter the body during medical treatments that break the skin—and cause an infection. Overall, fungal infections cost some $48 billion in the U.S. each year. And infection rates are increasing because, in an ironic twist, advanced medical therapies are enabling severely ill patients to live longer and, therefore, be exposed to this pathogen.

The first-ever case of a C. auris infection was reported in Japan in 2009, although an analysis of Candida samples dated the earliest strain to a 1996 sample from South Korea. Since then, five separate varieties – called clades, which are similar to strains among bacteria – developed independently in different geographies: South Asia, East Asia, South Africa, South America and, recently, Iran. So far, C. auris infections have been reported in 35 countries.

In the U.S., the first infection was reported in 2016, and the CDC started tracking it nationally two years later. During that time, 5,654 cases have been reported to the CDC, which only tracks U.S. data.

What’s more notable than the number of cases is their rate of increase. In 2016, new cases increased by 175 percent and, on average, they have approximately doubled every year. From 2016 through 2022, the number of infections jumped from 63 to 2,377, a roughly 37-fold increase.

“This reminds me of what we saw with epidemics from 2013 through 2020… with Ebola, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Robin Robinson, CEO of Spriovas and founding director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These epidemics started with a hockey stick trajectory, Robinson says—a gradual growth leading to a sharp spike, just like the shape of a hockey stick.

Another challenge is that right now medics don’t have rapid diagnostic tests for fungal infections. Currently, patients are often misdiagnosed because C. auris resembles several other easily treated fungi. Or they are diagnosed long after the infection begins and is harder to treat.

The problem is that existing diagnostics tests can only identify C. auris once it reaches the bloodstream. Yet, because this pathogen infects bodily tissues first, it should be possible to catch it much earlier before it becomes life-threatening. “We have to diagnose it before it reaches the bloodstream,” Walsh says.

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics.

“We need to focus on rapid diagnostic tests that do not rely on a positive blood culture,” says John Sperzel, president and CEO of T2 Biosystems, a company specializing in diagnostics solutions. Blood cultures typically take two to three days for the concentration of Candida to become large enough to detect. The company’s novel test detects about 90 percent of Candida species within three to five hours—thanks to its ability to spot minute quantities of the pathogen in blood samples instead of waiting for them to incubate and proliferate.

Unlike other Candida species C. auris thrives at human body temperatures

Adobe Stock

Tackling the resistance challenge

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics. The number of cases that stopped responding to echinocandin, the first-line therapy for most Candida infections, tripled in 2020, according to a study by the CDC.

Now, each of the first four clades shows varying levels of resistance to all three commonly prescribed classes of antifungal medications, such as azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. For example, 97 percent of infections from C. auris Clade I are resistant to fluconazole, 54 percent to voriconazole and 30 percent of amphotericin. Nearly half are resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. Even with Clade II fungi, which has the least resistance of all the clades, 11 to 14 percent have become resistant to fluconazole.

Anti-fungal therapies typically target specific chemical compounds present on fungi’s cell membranes, but not on human cells—otherwise the medicine would cause damage to our own tissues. Fluconazole and other azole antifungals target a compound called ergosterol, preventing the fungal cells from replicating. Over the years, however, C. auris evolved to resist it, so existing fungal medications don’t work as well anymore.

A newer class of drugs called echinocandins targets a different part of the fungal cell. “The echinocandins – like caspofungin – inhibit (a part of the fungi) involved in making glucan, which is an essential component of the fungal cell wall and is not found in human cells,” Fernandes says. New antifungal treatments are needed, she adds, but there are only a few magic bullets that will hit just the fungus and not the human cells.

Research to fight infections also has been challenged by a lack of government support. That is changing now that BARDA is requesting proposals to develop novel antifungals. “The scope includes C. auris, as well as antifungals following a radiological/nuclear emergency, says BARDA spokesperson Elleen Kane.

The remaining challenge is the number of patients available to participate in clinical trials. Large numbers are needed, but the available patients are quite sick and often die before trials can be completed. Consequently, few biopharmaceutical companies are developing new treatments for C. auris.

ClinicalTrials.gov reports only two drugs in development for invasive C. auris infections—those than can spread throughout the body rather than localize in one particular area, like throat or vaginal infections: ibrexafungerp by Scynexis, Inc., fosmanogepix, by Pfizer.

Scynexis’ ibrexafungerp appears active against C. auris and other emerging, drug-resistant pathogens. The FDA recently approved it as a therapy for vaginal yeast infections and it is undergoing Phase III clinical trials against invasive candidiasis in an attempt to keep the infection from spreading.

“Ibreafungerp is structurally different from other echinocandins,” Fernandes says, because it targets a different part of the fungus. “We’re lucky it has activity against C. auris.”

Pfizer’s fosmanogepix is in Phase II clinical trials for patients with invasive fungal infections caused by multiple Candida species. Results are showing significantly better survival rates for people taking fosmanogepix.

Although C. auris does pose a serious threat to healthcare worldwide, scientists try to stay optimistic—because they recognized the problem early enough, they might have solutions in place before the perfect storm hits. “There is a bit of hope,” says Robinson. “BARDA has finally been able to fund the development of new antifungal agents and, hopefully, this year we can get several new classes of antifungals into development.”

A new type of cancer therapy is shrinking deadly brain tumors with just one treatment

MRI scans after a new kind of immunotherapy for brain cancer show remarkable progress in one patient just days after the first treatment.

Few cancers are deadlier than glioblastomas—aggressive and lethal tumors that originate in the brain or spinal cord. Five years after diagnosis, less than five percent of glioblastoma patients are still alive—and more often, glioblastoma patients live just 14 months on average after receiving a diagnosis.

But an ongoing clinical trial at Mass General Cancer Center is giving new hope to glioblastoma patients and their families. The trial, called INCIPIENT, is meant to evaluate the effects of a special type of immune cell, called CAR-T cells, on patients with recurrent glioblastoma.

How CAR-T cell therapy works

CAR-T cell therapy is a type of cancer treatment called immunotherapy, where doctors modify a patient’s own immune system specifically to find and destroy cancer cells. In CAR-T cell therapy, doctors extract the patient’s T-cells, which are immune system cells that help fight off disease—particularly cancer. These T-cells are harvested from the patient and then genetically modified in a lab to produce proteins on their surface called chimeric antigen receptors (thus becoming CAR-T cells), which makes them able to bind to a specific protein on the patient’s cancer cells. Once modified, these CAR-T cells are grown in the lab for several weeks so that they can multiply into an army of millions. When enough cells have been grown, these super-charged T-cells are infused back into the patient where they can then seek out cancer cells, bind to them, and destroy them. CAR-T cell therapies have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat certain types of lymphomas and leukemias, as well as multiple myeloma, but haven’t been approved to treat glioblastomas—yet.

CAR-T cell therapies don’t always work against solid tumors, such as glioblastomas. Because solid tumors contain different kinds of cancer cells, some cells can evade the immune system’s detection even after CAR-T cell therapy, according to a press release from Massachusetts General Hospital. For the INCIPIENT trial, researchers modified the CAR-T cells even further in hopes of making them more effective against solid tumors. These second-generation CAR-T cells (called CARv3-TEAM-E T cells) contain special antibodies that attack EFGR, a protein expressed in the majority of glioblastoma tumors. Unlike other CAR-T cell therapies, these particular CAR-T cells were designed to be directly injected into the patient’s brain.

The INCIPIENT trial results

The INCIPIENT trial involved three patients who were enrolled in the study between March and July 2023. All three patients—a 72-year-old man, a 74-year-old man, and a 57-year-old woman—were treated with chemo and radiation and enrolled in the trial with CAR-T cells after their glioblastoma tumors came back.

The results, which were published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), were called “rapid” and “dramatic” by doctors involved in the trial. After just a single infusion of the CAR-T cells, each patient experienced a significant reduction in their tumor sizes. Just two days after receiving the infusion, the glioblastoma tumor of the 72-year-old man decreased by nearly twenty percent. Just two months later the tumor had shrunk by an astonishing 60 percent, and the change was maintained for more than six months. The most dramatic result was in the 57-year-old female patient, whose tumor shrank nearly completely after just one infusion of the CAR-T cells.

The results of the INCIPIENT trial were unexpected and astonishing—but unfortunately, they were also temporary. For all three patients, the tumors eventually began to grow back regardless of the CAR-T cell infusions. According to the press release from MGH, the medical team is now considering treating each patient with multiple infusions or prefacing each treatment with chemotherapy to prolong the response.

While there is still “more to do,” says co-author of the study neuro-oncologist Dr. Elizabeth Gerstner, the results are still promising. If nothing else, these second-generation CAR-T cell infusions may someday be able to give patients more time than traditional treatments would allow.

“These results are exciting but they are also just the beginning,” says Dr. Marcela Maus, a doctor and professor of medicine at Mass General who was involved in the clinical trial. “They tell us that we are on the right track in pursuing a therapy that has the potential to change the outlook for this intractable disease.”

A recent study in The Lancet Oncology showed that AI found 20 percent more cancers on mammogram screens than radiologists alone.

Since the early 2000s, AI systems have eliminated more than 1.7 million jobs, and that number will only increase as AI improves. Some research estimates that by 2025, AI will eliminate more than 85 million jobs.

But for all the talk about job security, AI is also proving to be a powerful tool in healthcare—specifically, cancer detection. One recently published study has shown that, remarkably, artificial intelligence was able to detect 20 percent more cancers in imaging scans than radiologists alone.

Published in The Lancet Oncology, the study analyzed the scans of 80,000 Swedish women with a moderate hereditary risk of breast cancer who had undergone a mammogram between April 2021 and July 2022. Half of these scans were read by AI and then a radiologist to double-check the findings. The second group of scans was read by two researchers without the help of AI. (Currently, the standard of care across Europe is to have two radiologists analyze a scan before diagnosing a patient with breast cancer.)

The study showed that the AI group detected cancer in 6 out of every 1,000 scans, while the radiologists detected cancer in 5 per 1,000 scans. In other words, AI found 20 percent more cancers than the highly-trained radiologists.

But even though the AI was better able to pinpoint cancer on an image, it doesn’t mean radiologists will soon be out of a job. Dr. Laura Heacock, a breast radiologist at NYU, said in an interview with CNN that radiologists do much more than simply screening mammograms, and that even well-trained technology can make errors. “These tools work best when paired with highly-trained radiologists who make the final call on your mammogram. Think of it as a tool like a stethoscope for a cardiologist.”

AI is still an emerging technology, but more and more doctors are using them to detect different cancers. For example, researchers at MIT have developed a program called MIRAI, which looks at patterns in patient mammograms across a series of scans and uses an algorithm to model a patient's risk of developing breast cancer over time. The program was "trained" with more than 200,000 breast imaging scans from Massachusetts General Hospital and has been tested on over 100,000 women in different hospitals across the world. According to MIT, MIRAI "has been shown to be more accurate in predicting the risk for developing breast cancer in the short term (over a 3-year period) compared to traditional tools." It has also been able to detect breast cancer up to five years before a patient receives a diagnosis.

The challenges for cancer-detecting AI tools now is not just accuracy. AI tools are also being challenged to perform consistently well across different ages, races, and breast density profiles, particularly given the increased risks that different women face. For example, Black women are 42 percent more likely than white women to die from breast cancer, despite having nearly the same rates of breast cancer as white women. Recently, an FDA-approved AI device for screening breast cancer has come under fire for wrongly detecting cancer in Black patients significantly more often than white patients.

As AI technology improves, radiologists will be able to accurately scan a more diverse set of patients at a larger volume than ever before, potentially saving more lives than ever.