Scientists fight to avoid a perfect storm of fungal infections

Doctors worry that fungal pathogens may cause the next pandemic.

Bacterial antibiotic resistance has been a concern in the medical field for several years. Now a new, similar threat is arising: drug-resistant fungal infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers antifungal and antimicrobial resistance to be among the world’s greatest public health challenges.

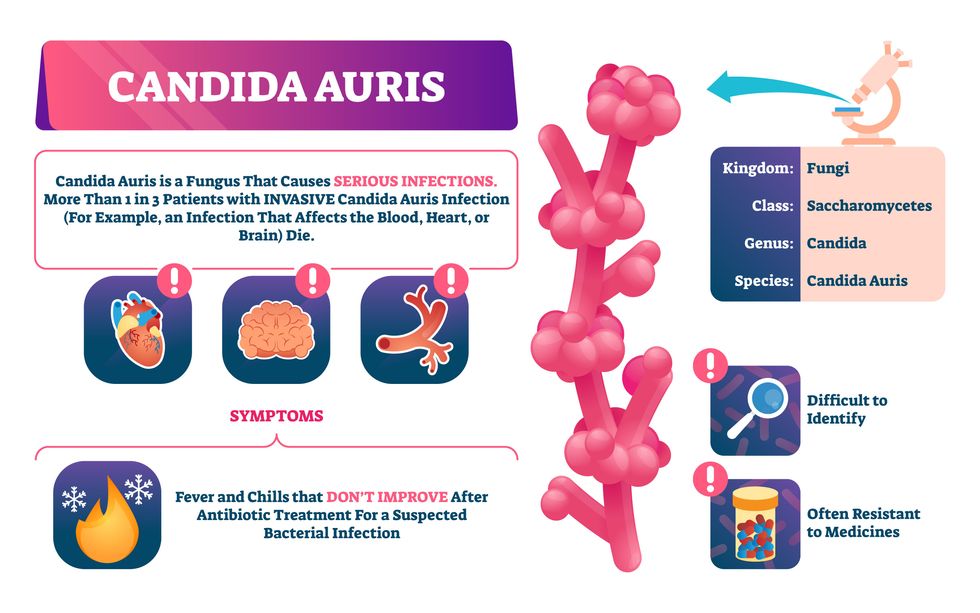

One particular type of fungal infection caused by Candida auris is escalating rapidly throughout the world. And to make matters worse, C. auris is becoming increasingly resistant to current antifungal medications, which means that if you develop a C. auris infection, the drugs your doctor prescribes may not work. “We’re effectively out of medicines,” says Thomas Walsh, founding director of the Center for Innovative Therapeutics and Diagnostics, a translational research center dedicated to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem. Walsh spoke about the challenges at a Demy-Colton Virtual Salon, one in a series of interactive discussions among life science thought leaders.

Although C. auris typically doesn’t sicken healthy people, it afflicts immunocompromised hospital patients and may cause severe infections that can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which the overwhelmed immune system begins to attack the body’s own organs. Between 30 and 60 percent of patients who contract a C. auris infection die from it, according to the CDC. People who are undergoing stem cell transplants, have catheters or have taken antifungal or antibiotic medicines are at highest risk. “We’re coming to a perfect storm of increasing resistance rates, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed patients worldwide and a bug that is adapting to higher temperatures as the climate changes,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the National BioDefense Science Board.

Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures.

Although medical professionals aren’t concerned at this point about C. auris evolving to affect healthy people, they worry that its presence in hospitals can turn routine surgeries into life-threatening calamities. “It’s coming,” says Fernandes. “It’s just a matter of time.”

An emerging global threat

“Fungi are found in the environment,” explains Fernandes, so Candida spores can easily wind up on people’s skin. In hospitals, they can be transferred from contact with healthcare workers or contaminated surfaces. Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures. It can enter the body during medical treatments that break the skin—and cause an infection. Overall, fungal infections cost some $48 billion in the U.S. each year. And infection rates are increasing because, in an ironic twist, advanced medical therapies are enabling severely ill patients to live longer and, therefore, be exposed to this pathogen.

The first-ever case of a C. auris infection was reported in Japan in 2009, although an analysis of Candida samples dated the earliest strain to a 1996 sample from South Korea. Since then, five separate varieties – called clades, which are similar to strains among bacteria – developed independently in different geographies: South Asia, East Asia, South Africa, South America and, recently, Iran. So far, C. auris infections have been reported in 35 countries.

In the U.S., the first infection was reported in 2016, and the CDC started tracking it nationally two years later. During that time, 5,654 cases have been reported to the CDC, which only tracks U.S. data.

What’s more notable than the number of cases is their rate of increase. In 2016, new cases increased by 175 percent and, on average, they have approximately doubled every year. From 2016 through 2022, the number of infections jumped from 63 to 2,377, a roughly 37-fold increase.

“This reminds me of what we saw with epidemics from 2013 through 2020… with Ebola, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Robin Robinson, CEO of Spriovas and founding director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These epidemics started with a hockey stick trajectory, Robinson says—a gradual growth leading to a sharp spike, just like the shape of a hockey stick.

Another challenge is that right now medics don’t have rapid diagnostic tests for fungal infections. Currently, patients are often misdiagnosed because C. auris resembles several other easily treated fungi. Or they are diagnosed long after the infection begins and is harder to treat.

The problem is that existing diagnostics tests can only identify C. auris once it reaches the bloodstream. Yet, because this pathogen infects bodily tissues first, it should be possible to catch it much earlier before it becomes life-threatening. “We have to diagnose it before it reaches the bloodstream,” Walsh says.

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics.

“We need to focus on rapid diagnostic tests that do not rely on a positive blood culture,” says John Sperzel, president and CEO of T2 Biosystems, a company specializing in diagnostics solutions. Blood cultures typically take two to three days for the concentration of Candida to become large enough to detect. The company’s novel test detects about 90 percent of Candida species within three to five hours—thanks to its ability to spot minute quantities of the pathogen in blood samples instead of waiting for them to incubate and proliferate.

Unlike other Candida species C. auris thrives at human body temperatures

Adobe Stock

Tackling the resistance challenge

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics. The number of cases that stopped responding to echinocandin, the first-line therapy for most Candida infections, tripled in 2020, according to a study by the CDC.

Now, each of the first four clades shows varying levels of resistance to all three commonly prescribed classes of antifungal medications, such as azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. For example, 97 percent of infections from C. auris Clade I are resistant to fluconazole, 54 percent to voriconazole and 30 percent of amphotericin. Nearly half are resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. Even with Clade II fungi, which has the least resistance of all the clades, 11 to 14 percent have become resistant to fluconazole.

Anti-fungal therapies typically target specific chemical compounds present on fungi’s cell membranes, but not on human cells—otherwise the medicine would cause damage to our own tissues. Fluconazole and other azole antifungals target a compound called ergosterol, preventing the fungal cells from replicating. Over the years, however, C. auris evolved to resist it, so existing fungal medications don’t work as well anymore.

A newer class of drugs called echinocandins targets a different part of the fungal cell. “The echinocandins – like caspofungin – inhibit (a part of the fungi) involved in making glucan, which is an essential component of the fungal cell wall and is not found in human cells,” Fernandes says. New antifungal treatments are needed, she adds, but there are only a few magic bullets that will hit just the fungus and not the human cells.

Research to fight infections also has been challenged by a lack of government support. That is changing now that BARDA is requesting proposals to develop novel antifungals. “The scope includes C. auris, as well as antifungals following a radiological/nuclear emergency, says BARDA spokesperson Elleen Kane.

The remaining challenge is the number of patients available to participate in clinical trials. Large numbers are needed, but the available patients are quite sick and often die before trials can be completed. Consequently, few biopharmaceutical companies are developing new treatments for C. auris.

ClinicalTrials.gov reports only two drugs in development for invasive C. auris infections—those than can spread throughout the body rather than localize in one particular area, like throat or vaginal infections: ibrexafungerp by Scynexis, Inc., fosmanogepix, by Pfizer.

Scynexis’ ibrexafungerp appears active against C. auris and other emerging, drug-resistant pathogens. The FDA recently approved it as a therapy for vaginal yeast infections and it is undergoing Phase III clinical trials against invasive candidiasis in an attempt to keep the infection from spreading.

“Ibreafungerp is structurally different from other echinocandins,” Fernandes says, because it targets a different part of the fungus. “We’re lucky it has activity against C. auris.”

Pfizer’s fosmanogepix is in Phase II clinical trials for patients with invasive fungal infections caused by multiple Candida species. Results are showing significantly better survival rates for people taking fosmanogepix.

Although C. auris does pose a serious threat to healthcare worldwide, scientists try to stay optimistic—because they recognized the problem early enough, they might have solutions in place before the perfect storm hits. “There is a bit of hope,” says Robinson. “BARDA has finally been able to fund the development of new antifungal agents and, hopefully, this year we can get several new classes of antifungals into development.”

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.