Two Conservative Icons Gave Opposite Advice on COVID-19. Those Misinformed Died in Higher Numbers, New Study Reports.

Sean Hannity (left) and Tucker Carlson each told their audience opposite information about the threat of COVID-19, with serious consequences for those misinformed.

The news sources that you consume can kill you - or save you. That's the fundamental insight of a powerful new study about the impact of watching either Sean Hannity's news show Hannity or Tucker Carlson's Tucker Carlson Tonight. One saved lives and the other resulted in more deaths, due to how each host covered COVID-19.

Carlson took the threat of COVID-19 seriously early on, more so than most media figures on the right or left.

This research illustrates the danger of falling for health-related misinformation due to judgment errors known as cognitive biases. These dangerous mental blindspots stem from the fact that our gut reactions evolved for the ancient savanna environment, not the modern world; yet the vast majority of advice on decision making is to "go with your gut," despite the fact that doing so leads to so many disastrous outcomes. These mental blind spots impact all areas of our life, from health to politics and even shopping, as a survey by a comparison purchasing website reveals. We need to be wary of cognitive biases in order to survive and thrive during this pandemic.

Sean Hannity vs. Tucker Carlson Coverage of COVID-19

Hannity and Tucker Carlson Tonight are the top two U.S. cable news shows, both on Fox News. Hannity and Carlson share very similar ideological profiles and have similar viewership demographics: older adults who lean conservative.

One notable difference, however, relates to how both approached coverage of COVID-19, especially in February and early March 2020. Researchers at the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago decided to study the health consequences of this difference.

Carlson took the threat of COVID-19 seriously early on, more so than most media figures on the right or left. Already on January 28, way earlier than most, Carlson spent a significant part of his show highlighting the serious dangers of a global pandemic. He continued his warnings throughout February. On February 25, Carlson told his viewers: "In this country, more than a million would die."

By contrast, Hannity was one of the Fox News hosts who took a more extreme position in downplaying COVID-19, frequently comparing it to the flu. On February 27, he said "And today, thankfully, zero people in the United States of America have died from the coronavirus. Zero. Now, let's put this in perspective. In 2017, 61,000 people in this country died from influenza, the flu. Common flu." Moreover, Hannity explicitly politicized COVID-19, claiming that "[Democrats] are now using the natural fear of a virus as a political weapon. And we have all the evidence to prove it, a shameful politicizing, weaponizing of, yes, the coronavirus."

However, after President Donald Trump declared COVID-19 a national emergency in mid-March, Hannity -- and other Fox News hosts -- changed their tune to align more with Carlson's, acknowledging the serious dangers of the virus.

The Behavior and Health Consequences

The Becker Friedman Institute researchers investigated whether the difference in coverage impacted behaviors. They conducted a nationally representative survey of over 1,000 people who watch Fox News at least once a week, evaluating both viewership and behavior changes in response to the pandemic, such as social distancing and improving hygiene.

Next, the study compared people's behavior changes to viewing patterns. The researchers found that "viewers of Hannity changed their behavior five days later than viewers of other shows, while viewers of Tucker Carlson Tonight changed their behavior three days earlier than viewers of other shows." The statistical difference was more than enough to demonstrate significance; in other words, it was extremely unlikely to occur by chance -- so unlikely as to be negligible.

Did these behavior changes lead to grave consequences? Indeed.

The paper compared the popularity of each show in specific counties to data on COVID-19 infections and deaths. Controlling for a wide variety of potential confounding variables, the study found that areas of the country where Hannity is more popular had more cases and deaths two weeks later, the time that it would take for the virus to start manifesting itself. By March 21st, the researchers found, there were 11 percent more deaths among Hannity's viewership than among Carlson's, again with a high degree of statistical significance.

The study's authors concluded: "Our findings indicate that provision of misinformation in the early stages of a pandemic can have important consequences for health outcomes."

Such outcomes stem from excessive trust that our minds tend to give those we see as having authority, even if they don't possess expertise in the relevant subject era.

Cognitive Biases and COVID-19 Misinformation

It's critically important to recognize that the study's authors did not seek to score any ideological points, given the broadly similar ideological profiles of the two hosts. The researchers simply explored the impact of accurate and inaccurate information about COVID-19 on the viewership. Clearly, the false information had deadly consequences.

Such outcomes stem from excessive trust that our minds tend to give those we see as having authority, even if they don't possess expertise in the relevant subject era -- such as media figures that we follow. This excessive trust - and consequent obedience - is called the "authority bias."

A related mental pattern is called "emotional contagion," in which we are unwittingly infected with the emotions of those we see as leaders. Emotions can motivate action even in the absence of formal authority, and are particularly important for those with informal authority, including thought leaders like Carlson and Hannity.

Thus, Hannity telling his audience that Democrats used anxiety about the virus as a political weapon led his audience to reject fears of COVID-19, even though such a reaction and consequent behavioral changes were the right response. Carlson's emphasis on the deadly nature of this illness motivated his audience to take appropriate precautions.

Authority bias and emotional contagion facilitate the spread of misinformation and its dangers, at least when we don't take the steps necessary to figure out the facts. Such steps can range from following best fact-checking practices to getting your information from news sources that commit publicly to being held accountable for truthfulness. Remember, the more important and impactful such information may be for your life, the more important it is to take the time to evaluate it accurately to help you make the best decisions.

What Will Make the Public Trust a COVID-19 Vaccine?

A successful deployment of an eventual vaccine will mean grappling with ongoing cultural tensions.

With a brighter future hanging on the hopes of an approved COVID-19 vaccine, is it possible to win over the minds of fearful citizens who challenge the value or safety of vaccination?

Globally, nine COVID-19 vaccines so far are being tested for safety in early phase human clinical trials.

It's a decades-old practice. With a dose injected into the arm of a healthy patient, doctors aim to prevent illness with a vaccine shot designed to trigger a person's immune system to fight serious infection without getting the disease.

This week, in fact, the U.S. frontrunner vaccine candidate, developed by Moderna, safely produced an immune response in the first eight healthy volunteers, the company announced. A large efficacy trial is planned to start in July. But if positive signals for safety and efficacy result from that trial, will that be enough to convince the public to broadly embrace a new vaccine?

"Throughout the history of vaccines there has always been a small vocal minority who don't believe vaccines work or don't trust the science," says sociologist and researcher Jennifer Reich, a professor at the University of Colorado in Denver and author of Calling the Shots: Why Parents Reject Vaccines.

Research indicates that only about 2 percent of the population say vaccines aren't necessary under any circumstance. Remarkably, a quarter to one third of American parents delay or reject the shots, not because they are anti-vaccine, but because they disapprove of the recommended timing or administration, says Reich.

Additionally, addressing distrust about how they come to market is key when talking to parents, workers or anyone targeted for a new vaccine, she says.

"When I talk to parents about why they reject vaccines for their kids, a lot of them say that they don't fully trust the process by which vaccines are regulated and tested," says Reich. "They don't trust that vaccine manufacturers -- which are for-profit companies -- are looking out for public health."

Balancing Act

Globally, nine COVID-19 vaccine candidates so far are being tested for safety in early phase human clinical trials and more than 100 are under development as scientists hustle to curtail the disease. Creating a new vaccine at a record pace requires a delicate balance of benefit and risk, says vaccinology expert Dr. Kathryn Edwards, professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn.

"We take safety very seriously," says Dr. Edwards. "We don't want something bad to happen, but we also realize that we have a terrible outbreak and we have a lot of people dying. We want to figure out how we can stop this."

In the U.S., all vaccine clinical trials have a data safety board of experts who monitor results for adverse reactions and red flags that should halt a study, notes Dr. Edwards. Any candidate that succeeds through safety and efficacy trials still requires review and approval by the Food and Drug Administration before a public launch.

Community vs. Individual

A major challenge to the deployment of a safe and effective coronavirus vaccine goes beyond the technical realm. A persistent all-out anti-vaccine sentiment has found a home and growing community on social media where conspiracies thrive. Main tenets of the movement are that vaccines are ineffective, unsafe and cause autism, despite abundant scientific evidence to the contrary.

Best-case scenario, more than one successful vaccine ascends with competing methods to achieve the same goal of preventing or lessening the severity of the COVID-19 virus.

In fact, widespread use of vaccines is considered by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention to be one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th Century. The World Health Organization estimates that between two million to three million deaths are avoided each year through immunization campaigns that employ vaccination to control life-threatening infectious diseases.

Most people reluctant to give their children vaccines, however, don't oppose them for everyone, but believe that they are a personal choice, says Reich.

"They think that vaccines are one strategy in personal health optimization, but they shouldn't be mandated for participation in any part of civil society," she says.

Vaccine hesitancy, like the teeter totter of social distancing acceptance, reflects the push and pull of individual versus community values, says Reich.

"A lot of people are saying, 'I take personal responsibility for my own health and I don't want a city or a county or state telling me what I should and shouldn't do,'" says Reich. "Then we also see calls for collective responsibility that says 'It's not your personal choice. This is about helping health systems function. This is about making sure vulnerable people are protected.'"

These same debates are likely to continue if a vaccine comes to market, she says.

Building Public Confidence

Reich offers solutions to address the conflict between embedded American norms and widespread embrace of an approved COVID-19 vaccine. Long-term goals: Stop blaming people when they get sick, treat illness as a community responsibility, make sick leave common for all workers, and improve public health systems.

"In the shorter run," says Reich, "health authorities and companies that might bring a vaccine to market need to work very hard to explain to the public why they should trust this vaccine and why they should use it."

The rush for a viable vaccine raises questions for consumers. To build public confidence, it's up to FDA reviewers, institutions and pharmaceutical companies to explain "what steps were skipped. What steps moved forward. How rigorous was safety testing. And to make that information clear to the public," says Reich.

Dr. Edwards says clinical trial timelines accelerated to test vaccines in humans make all the safeguards involved in the process that more compelling and important.

"There's no question we need a vaccine," she says. "But we also have to make sure that we don't harm people."

The Road Ahead

Think of manufacturing and distribution as key pitstops to keep the race for a vaccine on the road to the finish line. Both elements require substantial effort and consideration.

The speed of getting a vaccine to those who need it could hinge on the type of technology used to create it. Best-case scenario, more than one successful vaccine ascends with competing methods to achieve the same goal of preventing or lessening the severity of the COVID-19 virus.

Technological platforms fall into two basic camps, those that are proven and licensed for other viruses, and experimental approaches that may hold great promise but lack regulatory approval, says Maria Elena Bottazzi, co-director of Texas Children's Center for Vaccine Development at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Moderna, for instance, employs an experimental technology called messenger RNA (mRNA) that has produced the encouraging early results in human safety trials, although some researchers criticized the company for not making the data public. The mRNA vaccine instructs cells to make copies of the key COVID-19 spike protein, with the goal of then triggering production of immune cells that can recognize and attack the virus if it ever invades the body.

"We were already seeing a lot of dissent around questions of individual freedoms and community responsibilities."

Scientists always look for ways to incorporate new technologies into drug development, says Bottazzi. On the other hand, the more basic and generic the technology, theoretically, the faster production could ramp up if a vaccine proves successful through all phases of clinical trials, she says.

"I don't want to develop a vaccine in my lab, but then I don't have anybody to hand it off to because my process is not suitable" for manufacturing or scalability, says Bottazzi.

Researchers at the Baylor lab hope to repurpose a shelved vaccine developed for the genetically similar SARS virus, with a strategy to leverage what is already known instead of "starting from scratch" to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. A recombinant protein technology similar to that used for an approved Hepatitis B vaccine lets scientists focus on identifying a suitable vaccine target without the added worry of a novel platform, says Bottazzi.

The Finish Line

If and when a COVID-19 vaccine is approved is anyone's guess. Announcing a plan to hasten vaccine development via a program dubbed Operation Warp Speed, President Trump said recently one could be available "hopefully" by the end of the year or early 2021.

Scientists urge caution, noting that safe vaccines can take 10 years or more to develop. If a rushed vaccine turns out to have safety and efficacy issues, that could add ammunition to the anti-vaccine lobby.

Emergence of a successful vaccine requires an "enormous effort" with many complex systems from the lab all the way to manufacturing enough capacity to handle a pandemic, says Bottazzi.

"At the same time, you're developing it, you're really carefully assessing its safety and ability to be effective," she says, so it's important "not to get discouraged" if it takes longer than a year or more.

To gauge if a vaccine works on a broad scale, it would have to be delivered into communities where the virus is active. There are examples in history of life-saving vaccines going first to people who could pay for them and not to those who needed them most, says Reich.

"Agencies are going to have to think about how those distribution decisions are going to be made and who is going to make them and that will go a certain way toward reassuring the public," says Reich.

A Gallup survey last year found that vaccine confidence, in general, remains high, with 86 percent of Americans believing that vaccines are safer than the diseases that they are designed to prevent. Still, recent news organization polls indicate that roughly 20 to 25 percent of Americans say they won't or are unlikely to get a COVID-19 vaccine if one becomes available.

Until the 1980s, every vaccine to hit the market was appreciated; a culture of questioning science didn't exist in the same way as today, notes Reich. Time passed and attitudes changed.

"We were already having robust arguments nationally about what counts as an expert, what's the role of the government in daily life," says Reich. "We were already seeing a lot of dissent around questions of individual freedoms and community responsibilities. COVID-19 did not create those conflicts, but they've definitely become more visible since we've moved into this pandemic."

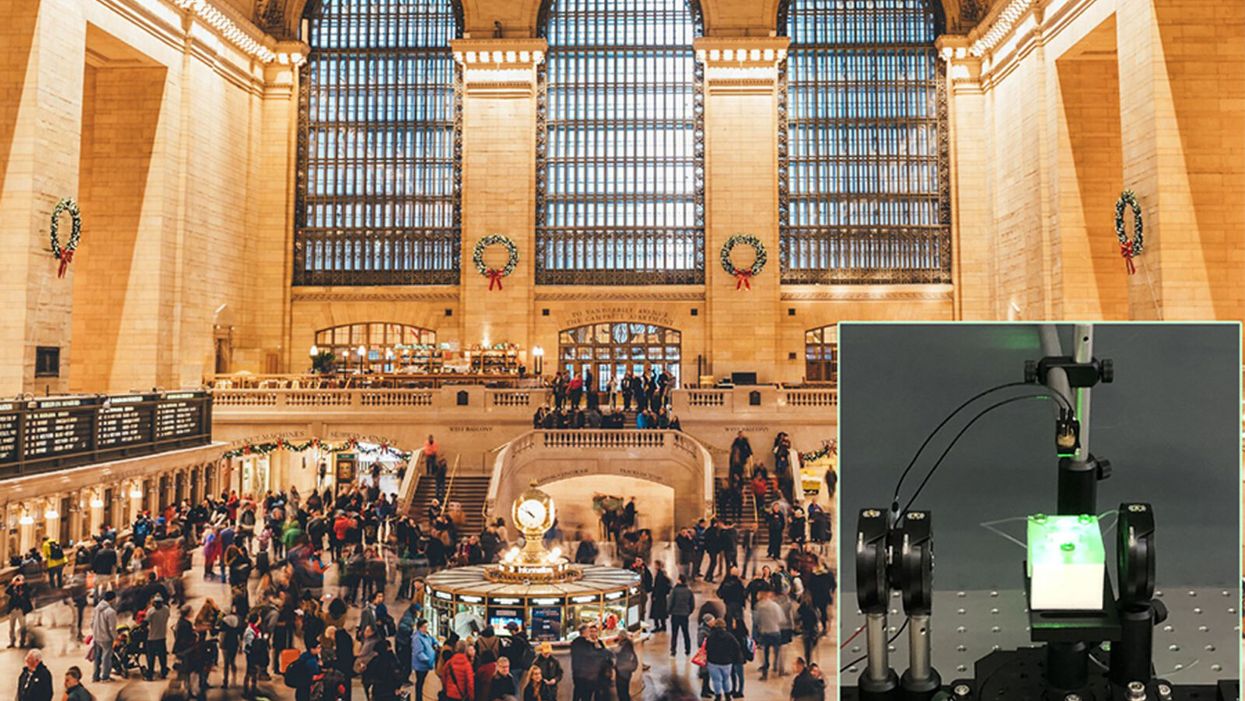

A biosensor in development (inset) could potentially be used to detect novel viruses in transit hubs like Grand Central Station in New York City.

The unprecedented scale and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused scientists and engineers around the world to stop whatever they were working on and shift their research toward understanding a novel virus instead.

"We have confidence that we can use our system in the next pandemic."

For Guangyu Qiu, normally an environmental engineer at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, that means finding a clever way to take his work on detecting pollution in the air and apply it to living pathogens instead. He's developing a new type of biosensor to make disease diagnostics and detection faster and more accurate than what's currently available.

But even though this pandemic was the impetus for designing a new biosensor, Qiu actually has his eye on future disease outbreaks. He admits that it's unlikely his device will play a role in quelling this virus, but says researchers already need to be thinking about how to make better tools to fight the next one — because there will be a next one.

"In the last 20 years, there [have been] three different coronavirus [outbreaks] ... so we have to prepare for the coming one," Qiu says. "We have confidence that we can use our system in the next pandemic."

"A Really, Really Neat Idea"

His main concern is the diagnostic tool that's currently front and center for testing patients for SARS-Cov-2, the virus causing the novel coronavirus disease. The tool, called PCR (short for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction), is the gold standard because it excels at detecting viruses in even very small samples of mucus. PCR can amplify genetic material in the limited sample and look for a genetic code matching the virus in question. But in many parts of the world, mucus samples have to be sent out to laboratories for that work, and results can take days to return. PCR is also notoriously prone to false positives and negatives.

"I read a lot of newspapers that report[ed] ... a lot of false negative or false positive results at the very beginning of the outbreak," Qiu says. "It's not good for protecting people to prevent further transmission of the disease."

So he set out to build a more sensitive device—one that's less likely to give you a false result. Qiu's biosensor relies on an idea similar to the dual-factor authentication required of anyone trying to access a secure webpage. Instead of verifying that a virus is really present by using one way of detecting genetic code, as with PCR, this biosensor asks for two forms of ID.

SARS-CoV-2 is what's called an RNA virus, which means it has a single strand of genetic code, unlike double-stranded DNA. Inside Qiu's biosensor are receptors with the complementary code for this particular virus' RNA; if the virus is present, its RNA will bind with the receptors, locking together like velcro. The biosensor also contains a prism and a laser that work together to verify that this RNA really belongs to SARS-CoV-2 by looking for a specific wavelength of light and temperature.

If the biosensor doesn't detect either, or only registers a match for one and not the other, then it can't produce a positive result. This multi-step authentication process helps make sure that the RNA binding with the receptors isn't a genetically similar coronavirus like SARS-CoV, known for its 2003 outbreak, or MERS-CoV, which caused an epidemic in 2012.

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The dual-feature design of this biosensor "is a really, really neat idea that I have not seen before with other sensor technology," says Erin Bromage, a professor of infection and immunology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth; he was not involved in designing or testing Qiu's biosensor. "It makes you feel more secure that when you have a positive, you've really got a positive."

The light and temperature sensors are not in themselves new inventions, but the combination is a first. The part of the device that uses light to detect particles is actually central to Qiu's normal stream of environmental research, and is a versatile tool he's been working with for a long time to detect aerosols in the atmosphere and heavy metals in drinking water.

Bromage says this is a plus. "It's not high-risk in the sense that how they do this is unique, or not validated. They've taken aspects of really proven technology and sort of combined it together."

This new biosensor is still a prototype that will take at least another 12 months to validate in real world scenarios, though. The device is sound from a biological perspective and is sensitive enough to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 — and to not be tricked by genetically similar viruses like SARS-CoV — but there is still a lot of engineering work that needs to be done in order for it to work outside the lab. Qiu says it's unlikely that the sensor will help minimize the impact of this pandemic, but the RNA receptors, prism, and laser inside the device can be customized to detect other viruses that may crop up in the future.

"If we choose another sequence—like SARS, like MERS, or like normal seasonal flu—we can detect other viruses, or even bacteria," Qiu says. "This device is very flexible."

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The Long-Term Vision: Hospitals and Transit Hubs

The device has been designed to connect with two other systems: an air sampler and a microprocessor because the goal is to make it portable, and able to pick up samples from the air in hospitals or public areas like train stations or airports. A virus could hopefully be detected before it silently spreads and erupts into another global pandemic. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been conflicting research about whether or not the virus is truly airborne (though it can be spread by droplets that briefly move through the air after a cough or sneeze), whereas the highly contagious RNA virus that causes measles can remain in the air for up to two hours.

"They've got a lot on the front end to work out," Bromage says. "They've got to work out how to capture and concentrate a virus, extract the RNA from the virus, and then get it onto the sensor. That's some pretty big hurdles, and may take some engineering that doesn't exist right now. But, if they can do that, then that works out really quite well."

One of the major obstacles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic has been in deploying accurate, quick tools that can be used for early detection of a virus outbreak and for later tracing its spread. That will still be true the next time a novel virus rears its head, and it's why Qiu feels that even if his biosensor can't help just yet, the research is still worth the effort.

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The dual-feature design of this biosensor "is a really, really neat idea that I have not seen before with other sensor technology," says Erin Bromage, a professor of infection and immunology at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth; he was not involved in designing or testing Qiu's biosensor. "It makes you feel more secure that when you have a positive, you've really got a positive."

The light and temperature sensors are not in themselves new inventions, but the combination is a first. The part of the device that uses light to detect particles is actually central to Qiu's normal stream of environmental research, and is a versatile tool he's been working with for a long time to detect aerosols in the atmosphere and heavy metals in drinking water.

Bromage says this is a plus. "It's not high-risk in the sense that how they do this is unique, or not validated. They've taken aspects of really proven technology and sort of combined it together."

This new biosensor is still a prototype that will take at least another 12 months to validate in real world scenarios, though. The device is sound from a biological perspective and is sensitive enough to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 — and to not be tricked by genetically similar viruses like SARS-CoV — but there is still a lot of engineering work that needs to be done in order for it to work outside the lab. Qiu says it's unlikely that the sensor will help minimize the impact of this pandemic, but the RNA receptors, prism, and laser inside the device can be customized to detect other viruses that may crop up in the future.

"If we choose another sequence—like SARS, like MERS, or like normal seasonal flu—we can detect other viruses, or even bacteria," Qiu says. "This device is very flexible."

It could also be fitted to detect future novel viruses once their genomes are sequenced.

The Long-Term Vision: Hospitals and Transit Hubs

The device has been designed to connect with two other systems: an air sampler and a microprocessor because the goal is to make it portable, and able to pick up samples from the air in hospitals or public areas like train stations or airports. A virus could hopefully be detected before it silently spreads and erupts into another global pandemic. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been conflicting research about whether or not the virus is truly airborne (though it can be spread by droplets that briefly move through the air after a cough or sneeze), whereas the highly contagious RNA virus that causes measles can remain in the air for up to two hours.

"They've got a lot on the front end to work out," Bromage says. "They've got to work out how to capture and concentrate a virus, extract the RNA from the virus, and then get it onto the sensor. That's some pretty big hurdles, and may take some engineering that doesn't exist right now. But, if they can do that, then that works out really quite well."

One of the major obstacles in containing the COVID-19 pandemic has been in deploying accurate, quick tools that can be used for early detection of a virus outbreak and for later tracing its spread. That will still be true the next time a novel virus rears its head, and it's why Qiu feels that even if his biosensor can't help just yet, the research is still worth the effort.