Food Poisoning Outbreaks Are Still A Problem. Powerful Tech Is Fighting Back.

The latest tools, like whole genome sequencing, are allowing food outbreaks to be identified and stopped more quickly.

With the pandemic at the forefront of everyone's minds, many people have wondered if food could be a source of coronavirus transmission. Luckily, that "seems unlikely," according to the CDC, but foodborne illnesses do still sicken a whopping 48 million people per year.

Whole genome sequencing is like "going from an eight-bit image—maybe like what you would see in Minecraft—to a high definition image."

In normal times, when there isn't a historic global health crisis infecting millions and affecting the lives of billions, foodborne outbreaks are real and frightening, potentially deadly, and can cause widespread fear of particular foods. Think of Romaine lettuce spreading E. coli last year— an outbreak that infected more than 500 people and killed eight—or peanut butter spreading salmonella in 2008, which infected 167 people.

The technologies available to detect and prevent the next foodborne disease outbreak have improved greatly over the past 30-plus years, particularly during the past decade, and better, more nimble technologies are being developed, according to experts in government, academia, and private industry. The key to advancing detection of harmful foodborne pathogens, they say, is increasing speed and portability of detection, and the precision of that detection.

Getting to Rapid Results

Researchers at Purdue University have recently developed a lateral flow assay that, with the help of a laser, can detect toxins and pathogenic E. coli. Lateral flow assays are cheap and easy to use; a good example is a home pregnancy test. You place a liquid or liquefied sample on a piece of paper designed to detect a single substance and soon after you get the results in the form of a colored line: yes or no.

"They're a great portable tool for us for food contaminant detection," says Carmen Gondhalekar, a fifth-year biomedical engineering graduate student at Purdue. "But one of the areas where paper-based lateral flow assays could use improvement is in multiplexing capability and their sensitivity."

J. Paul Robinson, a professor in Purdue's Colleges of Veterinary Medicine and Engineering, and Gondhalekar's advisor, agrees. "One of the fundamental problems that we have in detection is that it is hard to identify pathogens in complex samples," he says.

When it comes to foodborne disease outbreaks, you don't always know what substance you're looking for, so an assay made to detect only a single substance isn't always effective. The goal of the project at Purdue is to make assays that can detect multiple substances at once.

These assays would be more complex than a pregnancy test. As detailed in Gondhalekar's recent paper, a laser pulse helps create a spectral signal from the sample on the assay paper, and the spectral signal is then used to determine if any unique wavelengths associated with one of several toxins or pathogens are present in the sample. Though the handheld technology has yet to be built, the idea is that the results would be given on the spot. So someone in the field trying to track the source of a Salmonella infection could, for instance, put a suspected lettuce sample on the assay and see if it has the pathogen on it.

"What our technology is designed to do is to give you a rapid assessment of the sample," says Robinson. "The goal here is speed."

Seeing the Pathogen in "High-Def"

"One in six Americans will get a foodborne illness every year," according to Dr. Heather Carleton, a microbiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Enteric Diseases Laboratory Branch. But not every foodborne outbreak makes the news. In 2017 alone, the CDC monitored between 18 and 37 foodborne poison clusters per week and investigated 200 multi-state clusters. Hardboiled eggs, ground beef, chopped salad kits, raw oysters, frozen tuna, and pre-cut melon are just a taste of the foods that were investigated last year for different strains of listeria, salmonella, and E. coli.

At the heart of the CDC investigations is PulseNet, a national network of laboratories that uses DNA fingerprinting to detect outbreaks at local and regional levels. This is how it works: When a patient gets sick—with symptoms like vomiting and fever, for instance—they will go to a hospital or clinic for treatment. Since we're talking about foodborne illnesses, a clinician will likely take a stool sample from the patient and send it off to a laboratory to see if there is a foodborne pathogen, like salmonella, E. Coli, or another one. If it does contain a potentially harmful pathogen, then a bacterial isolate of that identified sample is sent to a regional public health lab so that whole genome sequencing can be performed.

Whole genome sequencing can differentiate "virtually all" strains of foodborne pathogens, no matter the species, according to the FDA.

Whole genome sequencing is a method for reading the entire genome of a bacterial isolate (or from any organism, for that matter). Instead of working with a couple dozen data points, now you're working with millions of base pairs. Carleton likes to describe it as "going from an eight-bit image—maybe like what you would see in Minecraft—to a high definition image," she says. "It's really an evolution of how we detect foodborne illnesses and identify outbreaks."

If the bacterial isolate matches another in the CDC's database, this means there could be a potential outbreak and an investigation may be started, with the goal of tracking the pathogen to its source.

Whole genome sequencing has been a relatively recent shift in foodborne disease detection. For more than 20 years, the standard technique for analyzing pathogens in foodborne disease outbreaks was pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. This method creates a DNA fingerprint for each sample in the form of a pattern of about 15-30 "bands," with each band representing a piece of DNA. Researchers like Carleton can use this fingerprint to see if two samples are from the same bacteria. The problem is that 15-30 bands are not enough to differentiate all isolates. Some isolates whose bands look very similar may actually come from different sources and some whose bands look different may be from the same source. But if you can see the entire DNA fingerprint, then you don't have that issue. That's where whole genome sequencing comes in.

Although the PulseNet team had piloted whole genome sequencing as early as 2013, it wasn't until July of last year that the transition to using whole genome sequencing for all pathogens was complete. Though whole genome sequencing requires far more computing power to generate, analyze, and compare those millions of data points, the payoff is huge.

Stopping Outbreaks Sooner

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acquired their first whole genome sequencers in 2008, according to Dr. Eric Brown, the Director of the Division of Microbiology in the FDA's Office of Regulatory Science. Since then, through their GenomeTrakr program, a network of more than 60 domestic and international labs, the FDA has sequenced and publicly shared more than 400,000 isolates. "The impact of what whole genome sequencing could do to resolve a foodborne outbreak event was no less impactful than when NASA turned on the Hubble Telescope for the first time," says Brown.

Whole genome sequencing has helped identify strains of Salmonella that prior methods were unable to differentiate. In fact, whole genome sequencing can differentiate "virtually all" strains of foodborne pathogens, no matter the species, according to the FDA. This means it takes fewer clinical cases—fewer sick people—to detect and end an outbreak.

And perhaps the largest benefit of whole genome sequencing is that these detailed sequences—the millions of base pairs—can imply geographic location. The genomic information of bacterial strains can be different depending on the area of the country, helping these public health agencies eventually track the source of outbreaks—a restaurant, a farm, a food-processing center.

Coming Soon: "Lab in a Backpack"

Now that whole genome sequencing has become the go-to technology of choice for analyzing foodborne pathogens, the next step is making the process nimbler and more portable. Putting "the lab in a backpack," as Brown says.

The CDC's Carleton agrees. "Right now, the sequencer we use is a fairly big box that weighs about 60 pounds," she says. "We can't take it into the field."

A company called Oxford Nanopore Technologies is developing handheld sequencers. Their devices are meant to "enable the sequencing of anything by anyone anywhere," according to Dan Turner, the VP of Applications at Oxford Nanopore.

"The sooner that we can see linkages…the sooner the FDA gets in action to mitigate the problem and put in some kind of preventative control."

"Right now, sequencing is very much something that is done by people in white coats in laboratories that are set up for that purpose," says Turner. Oxford Nanopore would like to create a new, democratized paradigm.

The FDA is currently testing these types of portable sequencers. "We're very excited about it. We've done some pilots, to be able to do that sequencing in the field. To actually do it at a pond, at a river, at a canal. To do it on site right there," says Brown. "This, of course, is huge because it means we can have real-time sequencing capability to stay in step with an actual laboratory investigation in the field."

"The timeliness of this information is critical," says Marc Allard, a senior biomedical research officer and Brown's colleague at the FDA. "The sooner that we can see linkages…the sooner the FDA gets in action to mitigate the problem and put in some kind of preventative control."

At the moment, the world is rightly focused on COVID-19. But as the danger of one virus subsides, it's only a matter of time before another pathogen strikes. Hopefully, with new and advancing technology like whole genome sequencing, we can stop the next deadly outbreak before it really gets going.

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

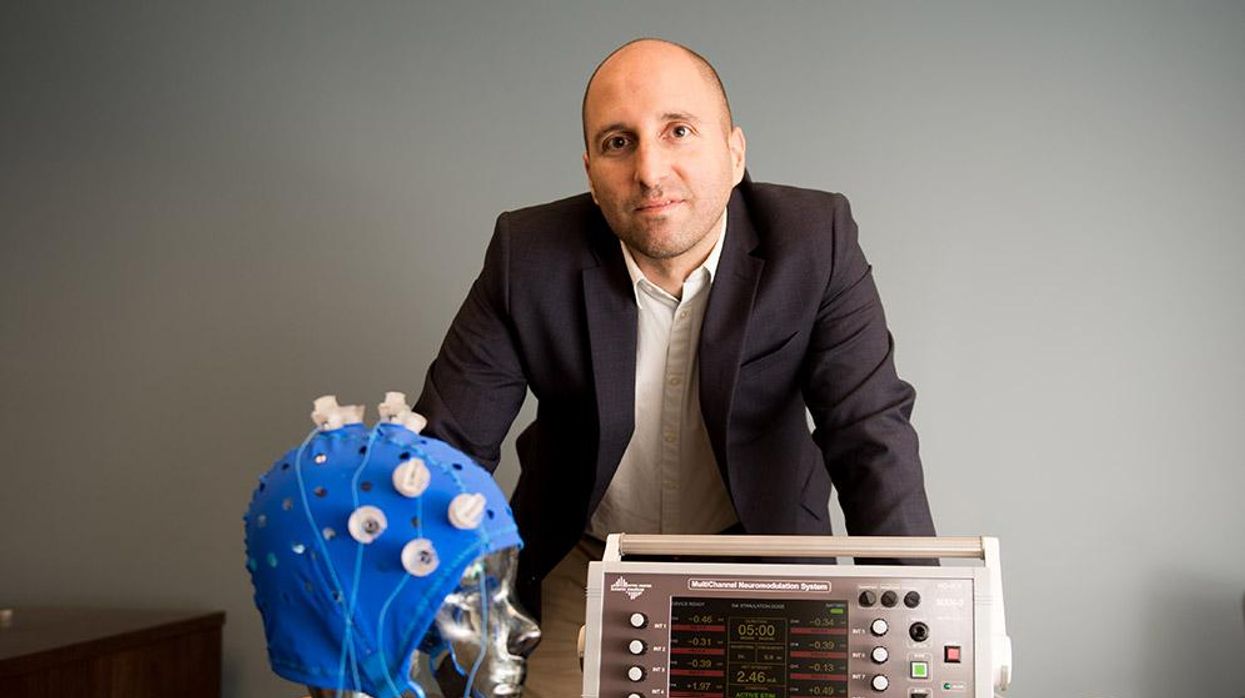

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”