Our devices are changing us

Tech-related injuries are becoming more common as many people depend on - and often develop addictions for - smart phones and computers.

In the 1990s, a mysterious virus spread throughout the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Lab—or that’s what the scientists who worked there thought. More of them rubbed their aching forearms and massaged their cricked necks as new computers were introduced to the AI Lab on a floor-by-floor basis. They realized their musculoskeletal issues coincided with the arrival of these new computers—some of which were mounted high up on lab benches in awkward positions—and the hours spent typing on them.

Today, these injuries have become more common in a society awash with smart devices, sleek computers, and other gadgets. And we don’t just get hurt from typing on desktop computers; we’re massaging our sore wrists from hours of texting and Facetiming on phones, especially as they get bigger in size.

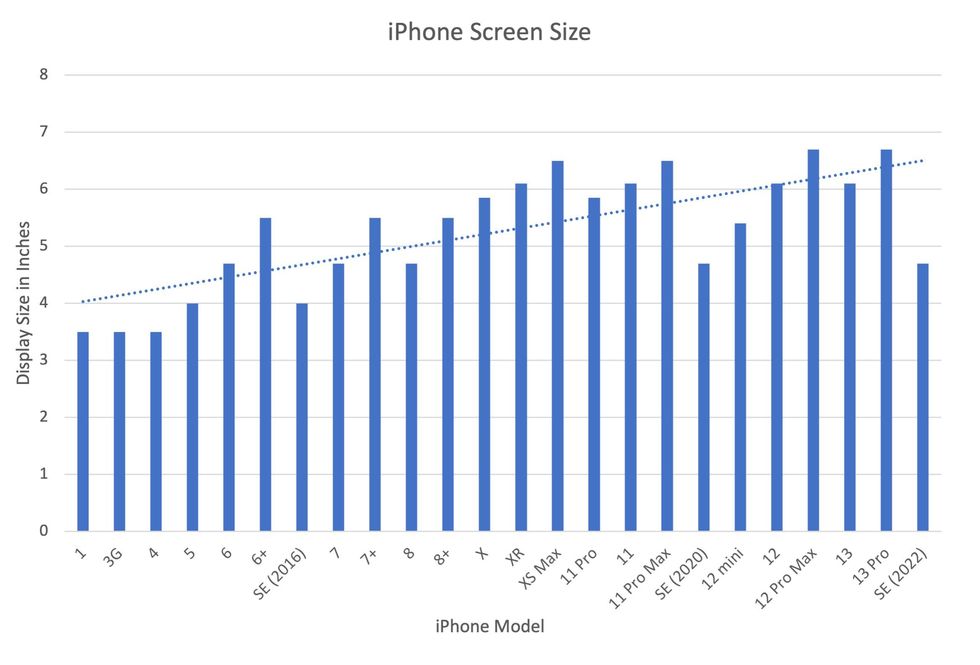

In 2007, the first iPhone measured 3.5-inches diagonally, a measurement known as the display size. That’s been nearly doubled by the newest iPhone 13 Pro, which has a 6.7-inch display. Other phones, too, like the Google Pixel 6 and the Samsung Galaxy S22, have bigger screens than their predecessors. Physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons have had to come up with names for a variety of new conditions: selfie elbow, tech neck, texting thumb. Orthopedic surgeon Sonya Sloan says she sees selfie elbow in younger kids and in women more often than men. She hears complaints related to technology once or twice a day.

The addictive quality of smartphones and social media means that people spend more time on their devices, which exacerbates injuries. According to Statista, 68 percent of those surveyed spent over three hours a day on their phone, and almost half spent five to six hours a day. Another report showed that people dedicate a third of their day to checking their phones, while the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has found that bigger screens, ideal for entertainment purposes, immerse their users more than smaller screens. Oversized screens also provide easier navigation and more space for those with bigger hands or trouble seeing.

But others with conditions like arthritis can benefit from smaller phones. In March of 2016, Apple released the iPhone SE with a display size of 4.7 inches—an inch smaller than the iPhone 7, released that September. Apple has since come out with two more versions of the diminutive iPhone SE, one in 2020 and another in 2022.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance science journalist, has the Google Pixel 6. She was drawn to the phone because Google marketed the Pixel 6’s camera as better at capturing different skin tones. But this phone boasts one of the largest display sizes on the market: 6.4 inches.

Senapathy was diagnosed with carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes in 2017 and fibromyalgia in 2019. She has had to create a curated ergonomic workplace setup, otherwise her wrists and hands get weak and tingly, and she’s had to adjust how she holds her phone to prevent pain flares.

Recently, Senapathy underwent an electromyography, or an EMG, in which doctors insert electrodes into muscles to measure their electrical activity. The electrical response of the muscles tells doctors whether the nerve cells and muscles are successfully communicating. Depending on her results, steroid shots and even surgery might be required. Senapathy wants to stick with her Pixel 6, but the pain she’s experiencing may push her to buy a smaller phone. Unfortunately, options for these modestly sized phones are more limited.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers like Senapathy to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable for creating addictive devices that lead to musculoskeletal injury?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance journalist, bought the Google Pixel 6 because of its high-quality camera, but she’s had to adjust how she holds the oversized phone to prevent pain flares.

Kavin Senapathy

A one-size-fits-all mentality for smartphones will continue to lead to injuries because every user has different wants and needs. S. Shyam Sundar, the founder of Penn State’s lab on media effects and a communications professor, says the needs for mobility and portability conflict with the desire for greater visibility. “The best thing a company can do is offer different sizes,” he says.

Joanna Bryson, an AI ethics expert and professor at The Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of the lack of choice we see comes from the fact that the markets have consolidated so much,” she says. “We want to make sure there’s sufficient diversity [of products].”

Consumers can still maintain some control despite the ubiquity of tech. Sloan, the orthopedic surgeon, has to pester her son to change his body positioning when using his tablet. Our heads get heavier as they bend forward: at rest, they weigh 12 pounds, but bent 60 degrees, they weigh 60. “I have to tell him, ‘Raise your head, son!’” she says. It’s important, Sloan explains, to consider that growth and development will affect ligaments and bones in the neck, potentially making kids even more vulnerable to injuries from misusing gadgets. She recommends that parents limit their kids’ tech time to alleviate strain. She also suggested that tech companies implement a timer to remind us to change our body positioning.

In 2017, Nan-Wei Gong, a former contractor for Google, founded Figur8, which uses wearable trackers to measure muscle function and joint movement. It’s like physical therapy with biofeedback. “Each unique injury has a different biomarker,” says Gong. “With Figur8, you are comparing yourself to yourself.” This allows an individual to self-monitor for wear and tear and strengthen an injury in a way that’s efficient and designed for their body. Gong noticed that the work-from-home model during the COVID-19 pandemic created a new set of ergonomic problems that resulted in injuries. Figur8 provides real-time data for these injuries because “behavioral change requires feedback.”

Gong worked on a project called Jacquard while at Google. Textile experts weave conductive thread into their fabric, and the result is a patch of the fabric—like the cuff of a Levi’s jacket—that responds to commands on your smartphone. One swipe can call your partner or check the weather. It was designed with cyclists in mind who can’t easily check their phones, and it’s part of a growing movement in the tech industry to deliver creative, hands-free design. Gong thinks that engineers at large corporations like Google have accessibility in mind; it’s part of what drives their decisions for new products.

Display sizes of iPhones have become larger over time.

Sourced from Screenrant https://screenrant.com/iphone-apple-release-chronological-order-smartphone/ and Apple Tech Specs: https://www.apple.com/iphone-se/specs/

Back in Germany, Joanna Bryson reminds us that products like smartphones should adhere to best practices. These rules may be especially important for phones and other products with AI that are addictive. Disclosure, accountability, and regulation are important for AI, she says. “The correct balance will keep changing. But we have responsibilities and obligations to each other.” She was on an AI Ethics Council at Google, but the committee was disbanded after only one week due to issues with one of their members.

Bryson was upset about the Council’s dissolution but has faith that other regulatory bodies will prevail. OECD.AI, and international nonprofit, has drafted policies to regulate AI, which countries can sign and implement. “As of July 2021, 46 governments have adhered to the AI principles,” their website reads.

Sundar, the media effects professor, also directs Penn State’s Center for Socially Responsible AI. He says that inclusivity is a crucial aspect of social responsibility and how devices using AI are designed. “We have to go beyond first designing technologies and then making them accessible,” he says. “Instead, we should be considering the issues potentially faced by all different kinds of users before even designing them.”

A new type of cancer therapy is shrinking deadly brain tumors with just one treatment

MRI scans after a new kind of immunotherapy for brain cancer show remarkable progress in one patient just days after the first treatment.

Few cancers are deadlier than glioblastomas—aggressive and lethal tumors that originate in the brain or spinal cord. Five years after diagnosis, less than five percent of glioblastoma patients are still alive—and more often, glioblastoma patients live just 14 months on average after receiving a diagnosis.

But an ongoing clinical trial at Mass General Cancer Center is giving new hope to glioblastoma patients and their families. The trial, called INCIPIENT, is meant to evaluate the effects of a special type of immune cell, called CAR-T cells, on patients with recurrent glioblastoma.

How CAR-T cell therapy works

CAR-T cell therapy is a type of cancer treatment called immunotherapy, where doctors modify a patient’s own immune system specifically to find and destroy cancer cells. In CAR-T cell therapy, doctors extract the patient’s T-cells, which are immune system cells that help fight off disease—particularly cancer. These T-cells are harvested from the patient and then genetically modified in a lab to produce proteins on their surface called chimeric antigen receptors (thus becoming CAR-T cells), which makes them able to bind to a specific protein on the patient’s cancer cells. Once modified, these CAR-T cells are grown in the lab for several weeks so that they can multiply into an army of millions. When enough cells have been grown, these super-charged T-cells are infused back into the patient where they can then seek out cancer cells, bind to them, and destroy them. CAR-T cell therapies have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat certain types of lymphomas and leukemias, as well as multiple myeloma, but haven’t been approved to treat glioblastomas—yet.

CAR-T cell therapies don’t always work against solid tumors, such as glioblastomas. Because solid tumors contain different kinds of cancer cells, some cells can evade the immune system’s detection even after CAR-T cell therapy, according to a press release from Massachusetts General Hospital. For the INCIPIENT trial, researchers modified the CAR-T cells even further in hopes of making them more effective against solid tumors. These second-generation CAR-T cells (called CARv3-TEAM-E T cells) contain special antibodies that attack EFGR, a protein expressed in the majority of glioblastoma tumors. Unlike other CAR-T cell therapies, these particular CAR-T cells were designed to be directly injected into the patient’s brain.

The INCIPIENT trial results

The INCIPIENT trial involved three patients who were enrolled in the study between March and July 2023. All three patients—a 72-year-old man, a 74-year-old man, and a 57-year-old woman—were treated with chemo and radiation and enrolled in the trial with CAR-T cells after their glioblastoma tumors came back.

The results, which were published earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), were called “rapid” and “dramatic” by doctors involved in the trial. After just a single infusion of the CAR-T cells, each patient experienced a significant reduction in their tumor sizes. Just two days after receiving the infusion, the glioblastoma tumor of the 72-year-old man decreased by nearly twenty percent. Just two months later the tumor had shrunk by an astonishing 60 percent, and the change was maintained for more than six months. The most dramatic result was in the 57-year-old female patient, whose tumor shrank nearly completely after just one infusion of the CAR-T cells.

The results of the INCIPIENT trial were unexpected and astonishing—but unfortunately, they were also temporary. For all three patients, the tumors eventually began to grow back regardless of the CAR-T cell infusions. According to the press release from MGH, the medical team is now considering treating each patient with multiple infusions or prefacing each treatment with chemotherapy to prolong the response.

While there is still “more to do,” says co-author of the study neuro-oncologist Dr. Elizabeth Gerstner, the results are still promising. If nothing else, these second-generation CAR-T cell infusions may someday be able to give patients more time than traditional treatments would allow.

“These results are exciting but they are also just the beginning,” says Dr. Marcela Maus, a doctor and professor of medicine at Mass General who was involved in the clinical trial. “They tell us that we are on the right track in pursuing a therapy that has the potential to change the outlook for this intractable disease.”

A recent study in The Lancet Oncology showed that AI found 20 percent more cancers on mammogram screens than radiologists alone.

Since the early 2000s, AI systems have eliminated more than 1.7 million jobs, and that number will only increase as AI improves. Some research estimates that by 2025, AI will eliminate more than 85 million jobs.

But for all the talk about job security, AI is also proving to be a powerful tool in healthcare—specifically, cancer detection. One recently published study has shown that, remarkably, artificial intelligence was able to detect 20 percent more cancers in imaging scans than radiologists alone.

Published in The Lancet Oncology, the study analyzed the scans of 80,000 Swedish women with a moderate hereditary risk of breast cancer who had undergone a mammogram between April 2021 and July 2022. Half of these scans were read by AI and then a radiologist to double-check the findings. The second group of scans was read by two researchers without the help of AI. (Currently, the standard of care across Europe is to have two radiologists analyze a scan before diagnosing a patient with breast cancer.)

The study showed that the AI group detected cancer in 6 out of every 1,000 scans, while the radiologists detected cancer in 5 per 1,000 scans. In other words, AI found 20 percent more cancers than the highly-trained radiologists.

But even though the AI was better able to pinpoint cancer on an image, it doesn’t mean radiologists will soon be out of a job. Dr. Laura Heacock, a breast radiologist at NYU, said in an interview with CNN that radiologists do much more than simply screening mammograms, and that even well-trained technology can make errors. “These tools work best when paired with highly-trained radiologists who make the final call on your mammogram. Think of it as a tool like a stethoscope for a cardiologist.”

AI is still an emerging technology, but more and more doctors are using them to detect different cancers. For example, researchers at MIT have developed a program called MIRAI, which looks at patterns in patient mammograms across a series of scans and uses an algorithm to model a patient's risk of developing breast cancer over time. The program was "trained" with more than 200,000 breast imaging scans from Massachusetts General Hospital and has been tested on over 100,000 women in different hospitals across the world. According to MIT, MIRAI "has been shown to be more accurate in predicting the risk for developing breast cancer in the short term (over a 3-year period) compared to traditional tools." It has also been able to detect breast cancer up to five years before a patient receives a diagnosis.

The challenges for cancer-detecting AI tools now is not just accuracy. AI tools are also being challenged to perform consistently well across different ages, races, and breast density profiles, particularly given the increased risks that different women face. For example, Black women are 42 percent more likely than white women to die from breast cancer, despite having nearly the same rates of breast cancer as white women. Recently, an FDA-approved AI device for screening breast cancer has come under fire for wrongly detecting cancer in Black patients significantly more often than white patients.

As AI technology improves, radiologists will be able to accurately scan a more diverse set of patients at a larger volume than ever before, potentially saving more lives than ever.