Hacking Your Own Genes: A Recipe for Disaster

Employees of ODIN, a consumer genetic design and engineering company, working out of their Bay Area garage start-up lab in 2016.

Editor's Note: Our Big Moral Question this month is: "Where should we draw a line, if any, between the use of gene editing for the prevention and treatment of disease, and for cosmetic enhancement?" It is illegal in the U.S. to develop human trials for the latter, even though some people think it should be acceptable. The most outspoken supporter recently resorted to self-experimentation using CRISPR in his own makeshift lab. But critics argue that "biohackers" like him are recklessly courting harm. LeapsMag invited a leading intellectual from the Center for Genetics and Society to share her perspective.

"I want to democratize science," says biohacker extraordinaire Josiah Zayner.

This is certainly a worthy-sounding sentiment. And it is central to the ethos of biohacking, a term that's developed a bit of sprawl. Biohacking can mean non-profit community biology labs that promote "citizen science," or clever but not necessarily safe or innocuous garage-based experiments with computers and genetics, or efforts at biological self-optimization via techniques including cybernetic implants, drug supplements, and intermittent fasting.

They appear to have given little thought to whether curiosity should be bound in any way by care for social consequence.

Against that messy background, what should we make of Zayner? The thirty-something ex-NASA scientist, who describes himself as "a global leader in the BioHacker movement," put his interpretation of democracy on display last October during a CRISPR-yourself performance at a San Francisco biotech conference. In that episode, he dramatically jabbed himself with a long needle, injecting his left forearm with a home-made gene-editing concoction that he said would disrupt his myostatin genes and bulk up his muscles.

Zayner sees himself, and is seen by some fellow biohackers, as a rebel hero: an intrepid scientific adventurer willing to risk his own well-being in the tradition of self-experimentation, eager to push the boundaries of established science in the service of forging innovative modes of discovery, ready to stand up to those stodgy bureaucrats at the FDA in the name of biohacker freedom.

To others, including some in the biohacker community, he's a publicity-seeking stunt man, perhaps deluded by touches of toxic masculinity and techno-entrepreneurial ideology, peddling snake-oil with oozing ramifications.

Zayner is hardly coy about his goals being larger than Popeye-like muscles. "I want to live in a world where people are genetically modifying themselves," he told FastCompany. "I think this is, like, literally, a new era of human beings," he mused to CBS in November. "It's gonna create a whole new species of humans."

Nor does he deign to conceal his tactics. The webpage of the company he launched to sell DIY gene-editing kits (which is advised by celebrity geneticist George Church) says that Zayner is "constantly pushing the boundaries of Science outside traditional environments." He is more explicit when performing: "Yes I am a criminal. And my crime is that of curiosity," he said last August to a biohacker audience in Oakland, which according to Gizmodo erupted in applause.

Regrettably, Zayner, along with some other biohackers and their defenders in the mainstream scientific world, appear to have given little thought to whether curiosity should be bound in any way by care for social consequence.

In December, the FDA issued a brief statement warning against using DIY kits for self-administered gene editing.

Though what's most directly at risk in Zayner's self-enhancement hack is his own safety, his bad-boy celebrity status is likely to encourage emulation. A few weeks after his San Francisco performance, 27-year-old Tristan Roberts took to Facebook Live to give himself a DIY gene modification injection to keep his HIV infection in check, because he doesn't like taking the regular medications that prevent AIDS. Whatever it was that he put into his body was provided by a company that Gizmodo describes as a "mysterious biotech firm with transhumanist leanings."

Zayner doesn't outright provide DIY gene hacks to others. But among his company's offerings are a free DIY Human CRISPR Guide and a $20 CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid that targets the human myostatin gene – the one that Zayner said he was targeting to make his muscles grow. Presumably to fend off legal problems, the product page says: "This product is not injectable or meant for direct human use" – a label as toothless as the fine print on cigarette packages that breaks the news that smoking causes cancer.

Some scientists warn that Zayner's style of biohacking carries considerable dangers. Microbiologist Brian Hanley, himself a self-experimenter who now opposes "biohacking humans," focuses on the technical difficulty of purifying what's being injected. "Screwing up can kill you from endotoxin," he says. "If you get in trouble, call me. I will do my best to instruct the physician how to save your life….But I make no guarantees you will survive."

Hanley also commented on the likely effectiveness of Zayner's effort: "Either Josiah Zayner is ignorant or he is deliberately misleading people. What he suggests cannot work as advertised."

Ensuring the safety and effectiveness of medical drugs and devices is the mandate of the US Food and Drug Administration. In December, the agency issued a brief statement warning against using DIY kits for self-administered gene editing, and saying flat out that selling them is against the law.

The stem cell field provides an unfortunate model of what can go wrong.

Zayner is dismissive of the safety risks. He asks in a Buzzfeed article whether DIY CRISPR should be considered more harmful than smoking or chemotherapy, "legal and socially acceptable activities that damage your genes." This is a strange line of argument, given the decades-long battles with the tobacco industry to raise awareness about smoking's significant harms, and since the side effects of chemotherapy are typically not undertaken by choice.

But the implications of what Zayner, Roberts, and some of their fellow biohackers are promoting ripple well beyond direct harms to individuals. Their rhetoric and vision affect the larger project of biomedicine, and the fraught relationships among drug researchers, pharmaceutical companies, clinical trial subjects, patients, and the public. Writing in Scientific American, Eleanor Pauwels of the Wilson Center, who is sympathetic to biohacking, lists the down sides: "blurred boundaries between treatments and self-experimentation, peer pressure to participate in trials, exploitation of vulnerable individuals, lack of oversight concerning quality control and risk of harm, and more."

These prospects are germane to the current state of human gene editing. After decades of dashed hopes, including deaths of research subjects, "gene therapy" may now be close to deserving the promise in its name. But with safety and efficacy still being evaluated, it's especially crucial to be honest about limitations as well as possibilities.

The stem cell field provides an unfortunate model of what can go wrong. Fifteen years ago, scientists, patient advocates, and even politicians routinely indulged in wildly over-optimistic enthusiasm about the imminence of stem cell therapies. That binge of irresponsible promotion helped create the current situation of widespread stem cell fraud: hundreds of clinics in the US alone selling unproven treatments to unsuspecting and sometimes desperate patients. Many have had their wallets lightened; some have gone blind or developed strange tumors that doctors have never before seen. The FDA is scrambling to address this still-worsening situation.

Zayner-style biohacking and promotion may also impact the ongoing controversy about whether new gene editing tools should be used in human reproduction to pre-determine the traits of future children and generations. Much of the widespread opposition to "human germline modification" is grounded in concern that it would lead to a society in which real or purported genetic advantages, marketed by fertility clinics to affluent parents, would exacerbate our already shameful levels of inequality and discrimination.

With powerful new technologies increasingly shaping the world, there's a lot riding on our capacity to democratize science. But as a society we don't yet have much practice at it.

Yet Zayner is all for it. In an interview in The Guardian, he comments, "DNA defines what a species is, and I imagine it wouldn't be too long into the future when the human species almost becomes a new species because of these modifications." He notes in a blog post, "We want to grow as a species and maybe change as a species. Whether that is curing disease or immortality or mutant powers is up to you."

This brings us back to Zayner's claim that he is working to democratize science.

The conviction that gene editing involves social and political challenges, not just technical matters, has been voiced at all points on the spectrum of perspective and uncertainty. But Zayner says there's been enough talk. "I want people to stop arguing about whether it's okay to use CRISPR or not use CRISPR….It's too late: I already made the choice for you. Argument over. Let's get on with it now. Let's use this to help people. Or to give people purple skin." (Emphasis added, in case there's any doubt about Zayner's commitment to democracy.)

With powerful new technologies increasingly shaping the world, there's a lot riding on our capacity to democratize science. But as a society we don't yet have much practice at it. In fact, we're not very sure what it would look like. It would clearly mean, as Arizona State University political scientist David Guston puts it, "considering the societal outcomes of research at least as attentively as the scientific and technological outputs." It would need broad participation and demand hard work.

The involvement of serious citizen scientists in such efforts, biohackers included, could be a very good thing. But Zayner's contributions to date have not been helpful.

[Ed. Note: Check out Zayner's perspective: "Genetic Engineering for All: The Last Great Frontier of Human Freedom." Then follow LeapsMag on social media to share your opinion.]

Scientists Are Working to Decipher the Puzzle of ‘Broken Heart Syndrome’

Elaine Kamil had just returned home after a few days of business meetings in 2013 when she started having chest pains. At first Kamil, then 66, wasn't worried—she had had some chest pain before and recently went to a cardiologist to do a stress test, which was normal.

"I can't be having a heart attack because I just got checked," she thought, attributing the discomfort to stress and high demands of her job. A pediatric nephrologist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, she takes care of critically ill children who are on dialysis or are kidney transplant patients. Supporting families through difficult times and answering calls at odd hours is part of her daily routine, and often leaves her exhausted.

She figured the pain would go away. But instead, it intensified that night. Kamil's husband drove her to the Cedars-Sinai hospital, where she was admitted to the coronary care unit. It turned out she wasn't having a heart attack after all. Instead, she was diagnosed with a much less common but nonetheless dangerous heart condition called takotsubo syndrome, or broken heart syndrome.

A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart is obstructed—such as when an artery is blocked—causing heart muscle tissue to die. In takotsubo syndrome, the blood flow isn't blocked, but the heart doesn't pump it properly. The heart changes its shape and starts to resemble a Japanese fishing device called tako-tsubo, a clay pot with a wider body and narrower mouth, used to catch octopus.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks," explains Noel Bairey Merz, the cardiologist at Cedar Sinai who Kamil went to see after she was discharged.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks."

But even though the heart isn't permanently damaged, mortality rates due to takotsubo syndrome are comparable to those of a heart attack, Merz notes—about 4-5 percent of patients die from the attack, and 20 percent within the next five years. "It's as bad as a heart attack," Merz says—only it's much less known, even to doctors. The condition affects only about 1 percent of people, and there are around 15,000 new cases annually. It's diagnosed using a cardiac ventriculogram, an imaging test that allows doctors to see how the heart pumps blood.

Scientists don't fully understand what causes Takotsubo syndrome, but it usually occurs after extreme emotional or physical stress. Doctors think it's triggered by a so-called catecholamine storm, a phenomenon in which the body releases too much catecholamines—hormones involved in the fight-or-flight response. Evolutionarily, when early humans lived in savannas or forests and had to either fight off predators or flee from them, these hormones gave our ancestors the needed strength and stamina to take either action. Released by nerve endings and by the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys, these hormones still flood our bodies in moments of stress, but an overabundance of them could sometimes be damaging.

Elaine Kamil

A study by scientists at Harvard Medical School linked increased risk of takotsubo to higher activity in the amygdala, a brain region responsible for emotions that's involved in responses to stress. The scientists believe that chronic stress makes people more susceptible to the syndrome. Notably, one small study suggested that the number of Takotsubo cases increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are no specific drugs to treat takotsubo, so doctors rely on supportive therapies, which include medications typically used for high blood pressure and heart failure. In most cases, the heart returns to its normal shape within a few weeks. "It's a spontaneous recovery—the catecholamine storm is resolved, the injury trigger is removed and the heart heals itself because our bodies have an amazing healing capacity," Merz says. It also helps that tissues remain intact. 'The heart cells don't die, they just aren't functioning properly for some time."

That's the good news. The bad news is that takotsubo is likely to strike again—in 5-20 percent of patients the condition comes back, sometimes more severe than before.

That's exactly what happened to Kamil. After getting her diagnosis in 2013, she realized that she actually had a previous takotsubo episode. In 2010, she experienced similar symptoms after her son died. "The night after he died, I was having severe chest pain at night, but I was too overwhelmed with grief to do anything about it," she recalls. After a while, the pain subsided and didn't return until three years later.

For weeks after her second attack, she felt exhausted, listless and anxious. "You lose confidence in your body," she says. "You have these little twinges on your chest, or if you start having arrhythmia, and you wonder if this is another episode coming up. It's really unnerving because you don't know how to read these cues." And that's very typical, Merz says. Even when the heart muscle appears to recover, patients don't return to normal right away. They have shortens of breath, they can't exercise, and they stay anxious and worried for a while.

Women over the age of 50 are diagnosed with takotsubo more often than other demographics. However, it happens in men too, although it typically strikes after physical stress, such as a triathlon or an exhausting day of cycling. Young people can also get takotsubo. Older patients are hospitalized more often, but younger people tend to have more severe complications. It could be because an older person may go for a jog while younger one may run a marathon, which would take a stronger toll on the body of a person who's predisposed to the condition.

Notably, the emotional stressors don't always have to be negative—the heart muscle can get out of shape from good emotions, too. "There have been case reports of takotsubo at weddings," Merz says. Moreover, one out of three or four takotsubo patients experience no apparent stress, she adds. "So it could be that it's not so much the catecholamine storm itself, but the body's reaction to it—the physiological reaction deeply embedded into out physiology," she explains.

Merz and her team are working to understand what makes people predisposed to takotsubo. They think a person's genetics play a role, but they haven't yet pinpointed genes that seem to be responsible. Genes code for proteins, which affect how the body metabolizes various compounds, which, in turn, affect the body's response to stress. Pinning down the protein involved in takotsubo susceptibility would allow doctors to develop screening tests and identify those prone to severe repeating attacks. It will also help develop medications that can either prevent it or treat it better than just waiting for the body to heal itself.

Researchers at the Imperial College London found that elevated levels of certain types of microRNAs—molecules involved in protein production—increase the chances of developing takotsubo.

In one study, researchers tried treating takotsubo in mice with a drug called suberanilohydroxamic acid, or SAHA, typically used for cancer treatment. The drug improved cardiac health and reversed the broken heart in rodents. It remains to be seen if the drug would have a similar effect on humans. But identifying a drug that shows promise is progress, Merz says. "I'm glad that there's research in this area."

This article was originally published by Leaps.org on July 28, 2021.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Did Anton the AI find a new treatment for a deadly cancer?

Researchers used a supercomputer to learn about the subtle movement of a cancer-causing molecule, and then they found the precise drug that can recognize that motion.

Bile duct cancer is a rare and aggressive form of cancer that is often difficult to diagnose. Patients with advanced forms of the disease have an average life expectancy of less than two years.

Many patients who get cancer in their bile ducts – the tubes that carry digestive fluid from the liver to the small intestine – have mutations in the protein FGFR2, which leads cells to grow uncontrollably. One treatment option is chemotherapy, but it’s toxic to both cancer cells and healthy cells, failing to distinguish between the two. Increasingly, cancer researchers are focusing on biomarker directed therapy, or making drugs that target a particular molecule that causes the disease – FGFR2, in the case of bile duct cancer.

A problem is that in targeting FGFR2, these drugs inadvertently inhibit the FGFR1 protein, which looks almost identical. This causes elevated phosphate levels, which is a sign of kidney damage, so doses are often limited to prevent complications.

In recent years, though, a company called Relay has taken a unique approach to picking out FGFR2, using a powerful supercomputer to simulate how proteins move and change shape. The team, leveraging this AI capability, discovered that FGFR2 and FGFR1 move differently, which enabled them to create a more precise drug.

Preliminary studies have shown robust activity of this drug, called RLY-4008, in FGFR2 altered tumors, especially in bile duct cancer. The drug did not inhibit FGFR1 or cause significant side effects. “RLY-4008 is a prime example of a precision oncology therapeutic with its highly selective and potent targeting of FGFR2 genetic alterations and resistance mutations,” says Lipika Goyal, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is a principal investigator of Relay’s phase 1-2 clinical trial.

Boosts from AI and a billionaire

Traditional drug design has been very much a case of trial and error, as scientists investigate many molecules to see which ones bind to the intended target and bind less to other targets.

“It’s being done almost blindly, without really being guided by structure, so it fails very often,” says Olivier Elemento, associate director of the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Cornell. “The issue is that they are not sampling enough molecules to cover some of the chemical space that would be specific to the target of interest and not specific to others.”

Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

Some scientists have tried to use X-rays of crystallized proteins to look at the structure of proteins and design better drugs. But they have failed to account for an important factor: proteins are moving and constantly folding into different shapes.

David Shaw, a hedge fund billionaire, wanted to help improve drug discovery and understood that a key obstacle was that computer models of molecular dynamics were limited; they simulated motion for less than 10 millionths of a second.

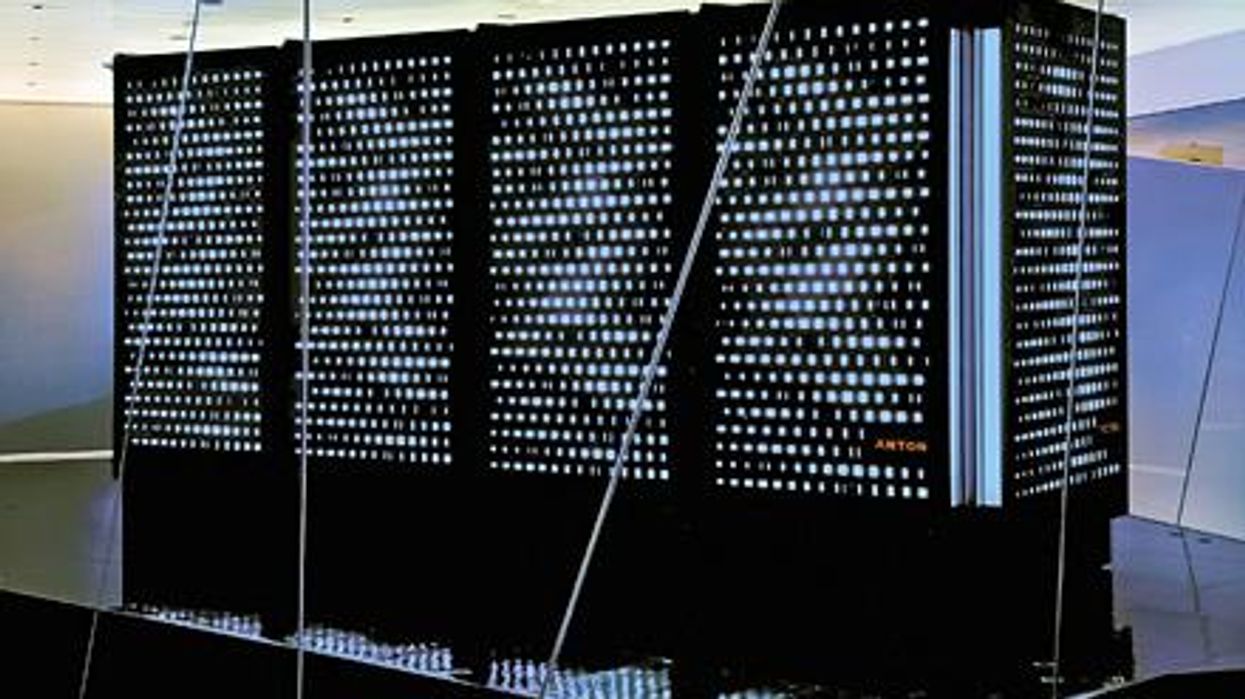

In 2001, Shaw set up his own research facility, D.E. Shaw Research, to create a supercomputer that would be specifically designed to simulate protein motion. Seven years later, he succeeded in firing up a supercomputer that can now conduct high speed simulations roughly 100 times faster than others. Called Anton, it has special computer chips to enable this speed, and its software is powered by AI to conduct many simulations.

After creating the supercomputer, Shaw teamed up with leading scientists who were interested in molecular motion, and they founded Relay Therapeutics.

Elemento believes that Relay’s approach is highly beneficial in designing a better drug for bile duct cancer. “Relay Therapeutics has a cutting-edge approach for molecular dynamics that I don’t believe any other companies have, at least not as advanced.” Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

How it works

Relay used both experimental and computational approaches to design RLY-4008. The team started out by taking X-rays of crystallized versions of both their intended target, FGFR2, and the almost identical FGFR1. This enabled them to get a 3D snapshot of each of their structures. They then fed the X-rays into the Anton supercomputer to simulate how the proteins were likely to move.

Anton’s simulations showed that the FGFR1 protein had a flap that moved more frequently than FGFR2. Based on this distinct motion, the team tried to design a compound that would recognize this flap shifting around and bind to FGFR2 while steering away from its more active lookalike.

For that, they went back Anton, using the supercomputer to simulate the behavior of thousands of potential molecules for over a year, looking at what made a particular molecule selective to the target versus another molecule that wasn’t. These insights led them to determine the best compounds to make and test in the lab and, ultimately, they found that RLY-4008 was the most effective.

Promising results so far

Relay began phase 1-2 trials in 2020 and will continue until 2024. Preliminary results showed that, in the 17 patients taking a 70 mg dose of RLY-4008, the drug worked to shrink tumors in 88 percent of patients. This was a significant increase compared to other FGFR inhibitors. For instance, Futibatinib, which recently got FDA approval, had a response rate of only 42 percent.

Across all dose levels, RLY-4008 shrank tumors by 63 percent in 38 patients. In more good news, the drug didn’t elevate their phosphate levels, which suggests that it could be taken without increasing patients’ risk for kidney disease.

“Objectively, this is pretty remarkable,” says Elemento. “In a small patient study, you have a molecule that is able to shrink tumors in such a high fraction of patients. It is unusual to see such good results in a phase 1-2 trial.”

A simulated future

The research team is continuing to use molecular dynamic simulations to develop other new drug, such as one that is being studied in patients with solid tumors and breast cancer.

As for their bile duct cancer drug, RLY-4008, Relay plans by 2024 to have tested it in around 440 patients. “The mature results of the phase 1-2 trial are highly anticipated,” says Goyal, the principal investigator of the trial.

Sameek Roychowdhury, an oncologist and associate professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University, highlights the need for caution. “This has early signs of benefit, but we will look forward to seeing longer term results for benefit and side effect profiles. We need to think a few more steps ahead - these treatments are like the ’Whack-a-Mole game’ where cancer finds a way to become resistant to each subsequent drug.”

“I think the issue is going to be how durable are the responses to the drug and what are the mechanisms of resistance,” says Raymond Wadlow, an oncologist at the Inova Medical Group who specializes in gastrointestinal and haematological cancer. “But the results look promising. It is a much more selective inhibitor of the FGFR protein and less toxic. It’s been an exciting development.”