Hacking Your Own Genes: A Recipe for Disaster

Employees of ODIN, a consumer genetic design and engineering company, working out of their Bay Area garage start-up lab in 2016.

Editor's Note: Our Big Moral Question this month is: "Where should we draw a line, if any, between the use of gene editing for the prevention and treatment of disease, and for cosmetic enhancement?" It is illegal in the U.S. to develop human trials for the latter, even though some people think it should be acceptable. The most outspoken supporter recently resorted to self-experimentation using CRISPR in his own makeshift lab. But critics argue that "biohackers" like him are recklessly courting harm. LeapsMag invited a leading intellectual from the Center for Genetics and Society to share her perspective.

"I want to democratize science," says biohacker extraordinaire Josiah Zayner.

This is certainly a worthy-sounding sentiment. And it is central to the ethos of biohacking, a term that's developed a bit of sprawl. Biohacking can mean non-profit community biology labs that promote "citizen science," or clever but not necessarily safe or innocuous garage-based experiments with computers and genetics, or efforts at biological self-optimization via techniques including cybernetic implants, drug supplements, and intermittent fasting.

They appear to have given little thought to whether curiosity should be bound in any way by care for social consequence.

Against that messy background, what should we make of Zayner? The thirty-something ex-NASA scientist, who describes himself as "a global leader in the BioHacker movement," put his interpretation of democracy on display last October during a CRISPR-yourself performance at a San Francisco biotech conference. In that episode, he dramatically jabbed himself with a long needle, injecting his left forearm with a home-made gene-editing concoction that he said would disrupt his myostatin genes and bulk up his muscles.

Zayner sees himself, and is seen by some fellow biohackers, as a rebel hero: an intrepid scientific adventurer willing to risk his own well-being in the tradition of self-experimentation, eager to push the boundaries of established science in the service of forging innovative modes of discovery, ready to stand up to those stodgy bureaucrats at the FDA in the name of biohacker freedom.

To others, including some in the biohacker community, he's a publicity-seeking stunt man, perhaps deluded by touches of toxic masculinity and techno-entrepreneurial ideology, peddling snake-oil with oozing ramifications.

Zayner is hardly coy about his goals being larger than Popeye-like muscles. "I want to live in a world where people are genetically modifying themselves," he told FastCompany. "I think this is, like, literally, a new era of human beings," he mused to CBS in November. "It's gonna create a whole new species of humans."

Nor does he deign to conceal his tactics. The webpage of the company he launched to sell DIY gene-editing kits (which is advised by celebrity geneticist George Church) says that Zayner is "constantly pushing the boundaries of Science outside traditional environments." He is more explicit when performing: "Yes I am a criminal. And my crime is that of curiosity," he said last August to a biohacker audience in Oakland, which according to Gizmodo erupted in applause.

Regrettably, Zayner, along with some other biohackers and their defenders in the mainstream scientific world, appear to have given little thought to whether curiosity should be bound in any way by care for social consequence.

In December, the FDA issued a brief statement warning against using DIY kits for self-administered gene editing.

Though what's most directly at risk in Zayner's self-enhancement hack is his own safety, his bad-boy celebrity status is likely to encourage emulation. A few weeks after his San Francisco performance, 27-year-old Tristan Roberts took to Facebook Live to give himself a DIY gene modification injection to keep his HIV infection in check, because he doesn't like taking the regular medications that prevent AIDS. Whatever it was that he put into his body was provided by a company that Gizmodo describes as a "mysterious biotech firm with transhumanist leanings."

Zayner doesn't outright provide DIY gene hacks to others. But among his company's offerings are a free DIY Human CRISPR Guide and a $20 CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid that targets the human myostatin gene – the one that Zayner said he was targeting to make his muscles grow. Presumably to fend off legal problems, the product page says: "This product is not injectable or meant for direct human use" – a label as toothless as the fine print on cigarette packages that breaks the news that smoking causes cancer.

Some scientists warn that Zayner's style of biohacking carries considerable dangers. Microbiologist Brian Hanley, himself a self-experimenter who now opposes "biohacking humans," focuses on the technical difficulty of purifying what's being injected. "Screwing up can kill you from endotoxin," he says. "If you get in trouble, call me. I will do my best to instruct the physician how to save your life….But I make no guarantees you will survive."

Hanley also commented on the likely effectiveness of Zayner's effort: "Either Josiah Zayner is ignorant or he is deliberately misleading people. What he suggests cannot work as advertised."

Ensuring the safety and effectiveness of medical drugs and devices is the mandate of the US Food and Drug Administration. In December, the agency issued a brief statement warning against using DIY kits for self-administered gene editing, and saying flat out that selling them is against the law.

The stem cell field provides an unfortunate model of what can go wrong.

Zayner is dismissive of the safety risks. He asks in a Buzzfeed article whether DIY CRISPR should be considered more harmful than smoking or chemotherapy, "legal and socially acceptable activities that damage your genes." This is a strange line of argument, given the decades-long battles with the tobacco industry to raise awareness about smoking's significant harms, and since the side effects of chemotherapy are typically not undertaken by choice.

But the implications of what Zayner, Roberts, and some of their fellow biohackers are promoting ripple well beyond direct harms to individuals. Their rhetoric and vision affect the larger project of biomedicine, and the fraught relationships among drug researchers, pharmaceutical companies, clinical trial subjects, patients, and the public. Writing in Scientific American, Eleanor Pauwels of the Wilson Center, who is sympathetic to biohacking, lists the down sides: "blurred boundaries between treatments and self-experimentation, peer pressure to participate in trials, exploitation of vulnerable individuals, lack of oversight concerning quality control and risk of harm, and more."

These prospects are germane to the current state of human gene editing. After decades of dashed hopes, including deaths of research subjects, "gene therapy" may now be close to deserving the promise in its name. But with safety and efficacy still being evaluated, it's especially crucial to be honest about limitations as well as possibilities.

The stem cell field provides an unfortunate model of what can go wrong. Fifteen years ago, scientists, patient advocates, and even politicians routinely indulged in wildly over-optimistic enthusiasm about the imminence of stem cell therapies. That binge of irresponsible promotion helped create the current situation of widespread stem cell fraud: hundreds of clinics in the US alone selling unproven treatments to unsuspecting and sometimes desperate patients. Many have had their wallets lightened; some have gone blind or developed strange tumors that doctors have never before seen. The FDA is scrambling to address this still-worsening situation.

Zayner-style biohacking and promotion may also impact the ongoing controversy about whether new gene editing tools should be used in human reproduction to pre-determine the traits of future children and generations. Much of the widespread opposition to "human germline modification" is grounded in concern that it would lead to a society in which real or purported genetic advantages, marketed by fertility clinics to affluent parents, would exacerbate our already shameful levels of inequality and discrimination.

With powerful new technologies increasingly shaping the world, there's a lot riding on our capacity to democratize science. But as a society we don't yet have much practice at it.

Yet Zayner is all for it. In an interview in The Guardian, he comments, "DNA defines what a species is, and I imagine it wouldn't be too long into the future when the human species almost becomes a new species because of these modifications." He notes in a blog post, "We want to grow as a species and maybe change as a species. Whether that is curing disease or immortality or mutant powers is up to you."

This brings us back to Zayner's claim that he is working to democratize science.

The conviction that gene editing involves social and political challenges, not just technical matters, has been voiced at all points on the spectrum of perspective and uncertainty. But Zayner says there's been enough talk. "I want people to stop arguing about whether it's okay to use CRISPR or not use CRISPR….It's too late: I already made the choice for you. Argument over. Let's get on with it now. Let's use this to help people. Or to give people purple skin." (Emphasis added, in case there's any doubt about Zayner's commitment to democracy.)

With powerful new technologies increasingly shaping the world, there's a lot riding on our capacity to democratize science. But as a society we don't yet have much practice at it. In fact, we're not very sure what it would look like. It would clearly mean, as Arizona State University political scientist David Guston puts it, "considering the societal outcomes of research at least as attentively as the scientific and technological outputs." It would need broad participation and demand hard work.

The involvement of serious citizen scientists in such efforts, biohackers included, could be a very good thing. But Zayner's contributions to date have not been helpful.

[Ed. Note: Check out Zayner's perspective: "Genetic Engineering for All: The Last Great Frontier of Human Freedom." Then follow LeapsMag on social media to share your opinion.]

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

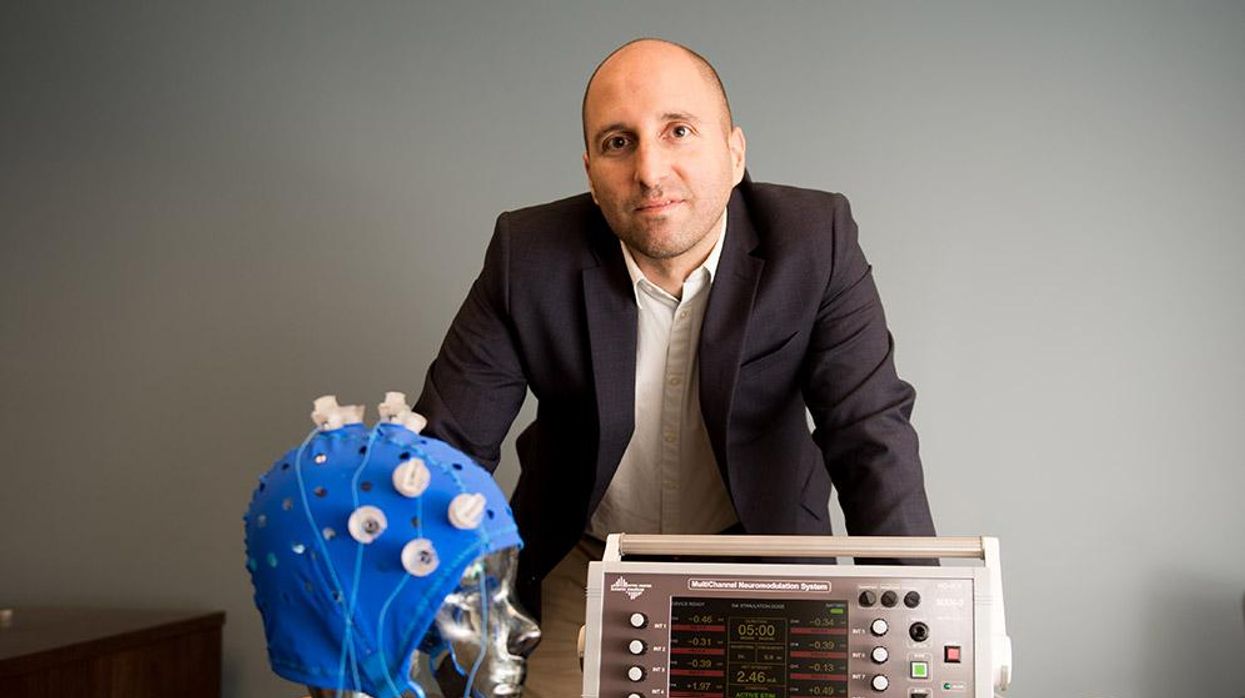

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”