How a Nobel-Prize Winner Fought Her Family, Nazis, and Bombs to Change our Understanding of Cells Forever

Rita Levi-Montalcini survived the Nazis and eventually won a Nobel Prize for her work to understand why certain cells grow so quickly.

When Rita Levi-Montalcini decided to become a scientist, she was determined that nothing would stand in her way. And from the beginning, that determination was put to the test. Before Levi-Montalcini became a Nobel Prize-winning neurobiologist, the first to discover and isolate a crucial chemical called Neural Growth Factor (NGF), she would have to battle both the sexism within her own family as well as the racism and fascism that was slowly engulfing her country

Levi-Montalcini was born to two loving parents in Turin, Italy at the turn of the 20th century. She and her twin sister, Paola, were the youngest of the family's four children, and Levi-Montalcini described her childhood as "filled with love and reciprocal devotion." But while her parents were loving, supportive and "highly cultured," her father refused to let his three daughters engage in any schooling beyond the basics. "He loved us and had a great respect for women," she later explained, "but he believed that a professional career would interfere with the duties of a wife and mother."

At age 20, Levi-Montalcini had finally had enough. "I realized that I could not possibly adjust to a feminine role as conceived by my father," she is quoted as saying, and asked his permission to finish high school and pursue a career in medicine. When her father reluctantly agreed, Levi-Montalcini was ecstatic: In just under a year, she managed to catch up on her mathematics, graduate high school, and enroll in medical school in Turin.

By 1936, Levi-Montalcini had graduated medical school at the top of her class and decided to stay on at the University of Turin as a research assistant for histologist and human anatomy professor Guiseppe Levi. Levi-Montalcini started studying nerve cells and nerve fibers – the tiny, slender tendrils that are threaded throughout our nerves and that determine what information each nerve can transmit. But it wasn't long before another enormous obstacle to her scientific career reared its head.

Science Under a Fascist Regime

Two years into her research assistant position, Levi-Montalcini was fired, along with every other "non-Aryan Italian" who held an academic or professional career, thanks to a series of antisemitic laws passed by Italy's then-leader Benito Mussolini. Forced out of her academic position, Levi-Montalcini went to Belgium for a fellowship at a neurological institute in Brussels – but then was forced back to Turin when the German army invaded.

Levi-Montalcini decided to keep researching. She and Guiseppe Levi built a makeshift lab in Levi-Montalcini's apartment, borrowing chicken eggs from local farmers and using sewing needles to dissect them. By dissecting the chicken embryos from her bedroom laboratory, she was able to see how nerve fibers formed and died. The two continued this research until they were interrupted again – this time, by British air raids. Levi-Montalcini fled to a country cottage to continue her research, and then two years later was forced into hiding when the German army invaded Italy. Levi-Montalcini and her family assumed different identities and lived with non-Jewish friends in Florence to survive the Holocaust. Despite all of this, Levi-Montalcini continued her work, dissecting chicken embryos from her hiding place until the end of the war.

"The discovery of NGF really changed the world in which we live, because now we knew that cells talk to other cells, and that they use soluble factors. It was hugely important."

A Post-War Discovery

Several years after the war, when Levi-Montalcini was once again working at the University of Turin, a German embryologist named Viktor Hamburger invited her to Washington University in St. Louis. Hamburger was impressed by Levi-Montalcini's research with her chicken embryos, and secured an opportunity for her to continue her work in America. The invitation would "change the course of my life," Levi-Montalcini would later recall.

During her fellowship, Montalcini grew tumors in mice and then transferred them to chick embryos in order to see how it would affect the chickens. To her surprise, she noticed that introducing the tumor samples would cause nerve fibers to grow rapidly. From this, Levi-Montalcini discovered and was able to isolate a protein that she determined was able to cause this rapid growth. She later named this Nerve Growth Factor, or NGF.

From there, Levi-Montalcini and her team launched new experiments to test NGF, injecting it and repressing it to see the effect it had in a test subject's body. When the team injected NGF into embryonic mice, they observed nerve growth, as well as the mouse pups developing faster – their eyes opening earlier and their teeth coming in sooner – than the untreated group. When the team purified the NGF extract, however, it had no effect, leading the team to believe that something else in the crude extract of NGF was influencing the growth of the newborn mice. Stanley Cohen, Levi-Montalcini's colleague, identified another growth factor called EGF – epidermal growth factor – that caused the mouse pups' eyes and teeth to grow so quickly.

Levi-Montalcini continued to experiment with NGF for the next several decades at Washington University, illuminating how NGF works in our body. When Levi-Montalcini injected newborn mice with an antiserum for NGF, for example, her team found that it "almost completely deprived the animals of a sympathetic nervous system." Other experiments done by Levi-Montalcini and her colleagues helped show the role that NGF plays in other important biological processes, such as the regulation of our immune system and ovulation.

"The discovery of NGF really changed the world in which we live, because now we knew that cells talk to other cells, and that they use soluble factors. It was hugely important," said Bill Mobley, Chair of the Department of Neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

Her Lasting Legacy

After years of setbacks, Levi-Montalcini's groundbreaking work was recognized in 1986, when she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her discovery of NGF (Cohen, her colleague who discovered EGF, shared the prize). Researchers continue to study NGF even to this day, and the continued research has been able to increase our understanding of diseases like HIV and Alzheimer's.

Levi-Montalcini never stopped researching either: In January 2012, at the age of 102, Levi-Montalcini published her last research paper in the journal PNAS, making her the oldest member of the National Academy of Science to do so. Before she died in December 2012, she encouraged other scientists who would suffer setbacks in their careers to keep pursuing their passions. "Don't fear the difficult moments," Levi-Montalcini is quoted as saying. "The best comes from them."

Researchers advance drugs that treat pain without addiction

New therapies are using creative approaches that target the body’s sensory neurons, which send pain signals to the brain.

Opioids are one of the most common ways to treat pain. They can be effective but are also highly addictive, an issue that has fueled the ongoing opioid crisis. In 2020, an estimated 2.3 million Americans were dependent on prescription opioids.

Opioids bind to receptors at the end of nerve cells in the brain and body to prevent pain signals. In the process, they trigger endorphins, so the brain constantly craves more. There is a huge risk of addiction in patients using opioids for chronic long-term pain. Even patients using the drugs for acute short-term pain can become dependent on them.

Scientists have been looking for non-addictive drugs to target pain for over 30 years, but their attempts have been largely ineffective. “We desperately need alternatives for pain management,” says Stephen E. Nadeau, a professor of neurology at the University of Florida.

A “dimmer switch” for pain

Paul Blum is a professor of biological sciences at the University of Nebraska. He and his team at Neurocarrus have created a drug called N-001 for acute short-term pain. N-001 is made up of specially engineered bacterial proteins that target the body’s sensory neurons, which send pain signals to the brain. The proteins in N-001 turn down pain signals, but they’re too large to cross the blood-brain barrier, so they don’t trigger the release of endorphins. There is no chance of addiction.

When sensory neurons detect pain, they become overactive and send pain signals to the brain. “We wanted a way to tone down sensory neurons but not turn them off completely,” Blum reveals. The proteins in N-001 act “like a dimmer switch, and that's key because pain is sensation overstimulated.”

Blum spent six years developing the drug. He finally managed to identify two proteins that form what’s called a C2C complex that changes the structure of a subunit of axons, the parts of neurons that transmit electrical signals of pain. Changing the structure reduces pain signaling.

“It will be a long path to get to a successful clinical trial in humans," says Stephen E. Nadeau, professor of neurology at the University of Florida. "But it presents a very novel approach to pain reduction.”

Blum is currently focusing on pain after knee and ankle surgery. Typically, patients are treated with anesthetics for a short time after surgery. But anesthetics usually only last for 4 to 6 hours, and long-term use is toxic. For some, the pain subsides. Others continue to suffer after the anesthetics have worn off and start taking opioids.

N-001 numbs sensation. It lasts for up to 7 days, much longer than any anesthetic. “Our goal is to prolong the time before patients have to start opioids,” Blum says. “The hope is that they can switch from an anesthetic to our drug and thereby decrease the likelihood they're going to take the opioid in the first place.”

Their latest animal trial showed promising results. In mice, N-001 reduced pain-like behaviour by 90 percent compared to the control group. One dose became effective in two hours and lasted a week. A high dose had pain-relieving effects similar to an opioid.

Professor Stephen P. Cohen, director of pain operations at John Hopkins, believes the Neurocarrus approach has potential but highlights the need to go beyond animal testing. “While I think it's promising, it's an uphill battle,” he says. “They have shown some efficacy comparable to opioids, but animal studies don't translate well to people.”

Nadeau, the University of Florida neurologist, agrees. “It will be a long path to get to a successful clinical trial in humans. But it presents a very novel approach to pain reduction.”

Blum is now awaiting approval for phase I clinical trials for acute pain. He also hopes to start testing the drug's effect on chronic pain.

Learning from people who feel no pain

Like Blum, a pharmaceutical company called Vertex is focusing on treating acute pain after surgery. But they’re doing this in a different way, by targeting a sodium channel that plays a critical role in transmitting pain signals.

In 2004, Stephen Waxman, a neurology professor at Yale, led a search for genetic pain anomalies and found that biologically related people who felt no pain despite fractures, burns and even childbirth had mutations in the Nav1.7 sodium channel. Further studies in other families who experienced no pain showed similar mutations in the Nav1.8 sodium channel.

Scientists set out to modify these channels. Many unsuccessful efforts followed, but Vertex has now developed VX-548, a medicine to inhibit Nav1.8. Typically, sodium ions flow through sodium channels to generate rapid changes in voltage which create electrical pulses. When pain is detected, these pulses in the Nav1.8 channel transmit pain signals. VX-548 uses small molecules to inhibit the channel from opening. This blocks the flow of sodium ions and the pain signal. Because Nav1.8 operates only in peripheral nerves, located outside the brain, VX-548 can relieve pain without any risk of addiction.

"Frankly we need drugs for chronic pain more than acute pain," says Waxman.

The team just finished phase II clinical trials for patients following abdominoplasty surgery and bunionectomy surgery.

After abdominoplasty surgery, 76 patients were treated with a high dose of VX-548. Researchers then measured its effectiveness in reducing pain over 48 hours, using the SPID48 scale, in which higher scores are desirable. The score for Vertex’s drug was 110.5 compared to 72.7 in the placebo group, whereas the score for patients taking an opioid was 85.2. The study involving bunionectomy surgery showed positive results as well.

Waxman, who has been at the forefront of studies into Nav1.7 and Nav1.8, believes that Vertex's results are promising, though he highlights the need for further clinical trials.

“Blocking Nav1.8 is an attractive target,” he says. “[Vertex is] studying pain that is relatively simple and uniform, and that's key to having a drug trial that is informative. But the study needs to be replicated and frankly we need drugs for chronic pain more than acute pain. If this is borne out by additional studies, it's one important step in a journey.”

Vertex will be launching phase III trials later this year.

Finding just the right amount of Nerve Growth Factor

Whereas Neurocarrus and Vertex are targeting short-term pain, a company called Levicept is concentrating on relieving chronic osteoarthritis pain. Around 32.5 million Americans suffer from osteoarthritis. Patients commonly take NSAIDs, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but they cannot be taken long-term. Some take opioids but they aren't very effective.

Levicept’s drug, Levi-04, is designed to modify a signaling pathway associated with pain. Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) is a neurotrophin: it’s involved in nerve growth and function. NGF signals by attaching to receptors. In pain there are excess neurotrophins attaching to receptors and activating pain signals.

“What Levi-04 does is it returns the natural equilibrium of neurotrophins,” says Simon Westbrook, the CEO and founder of Levicept. It stabilizes excess neurotrophins so that the NGF pathway does not signal pain. Levi-04 isn't addictive since it works within joints and in nerves outside the brain.

Westbrook was initially involved in creating an anti-NGF molecule for Pfizer called Tanezumab. At first, Tanezumab seemed effective in clinical trials and other companies even started developing their own versions. However, a problem emerged. Tanezumab caused rapidly progressive osteoarthritis, or RPOA, in some patients because it completely removed NGF from the system. NGF is not just involved in pain signalling, it’s also involved in bone growth and maintenance.

Levicept has found a way to modify the NGF pathway without completely removing NGF. They have now finished a small-scale phase I trial mainly designed to test safety rather than efficacy. “We demonstrated that Levi-04 is safe and that it bound to its target, NGF,” says Westbrook. It has not caused RPOA.

Professor Philip Conaghan, director of the Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, believes that Levi-04 has potential but urges the need for caution. “At this early stage of development, their molecule looks promising for osteoarthritis pain,” he says. “They will have to watch out for RPOA which is a potential problem.”

Westbrook starts phase II trials with 500 patients this summer to check for potential side effects and test the drug’s efficacy.

There is a real push to find an effective alternative to opioids. “We have a lot of work to do,” says Professor Waxman. “But I am confident that we will be able to develop new, much more effective pain therapies.”

Tech-related injuries are becoming more common as many people depend on - and often develop addictions for - smart phones and computers.

In the 1990s, a mysterious virus spread throughout the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Lab—or that’s what the scientists who worked there thought. More of them rubbed their aching forearms and massaged their cricked necks as new computers were introduced to the AI Lab on a floor-by-floor basis. They realized their musculoskeletal issues coincided with the arrival of these new computers—some of which were mounted high up on lab benches in awkward positions—and the hours spent typing on them.

Today, these injuries have become more common in a society awash with smart devices, sleek computers, and other gadgets. And we don’t just get hurt from typing on desktop computers; we’re massaging our sore wrists from hours of texting and Facetiming on phones, especially as they get bigger in size.

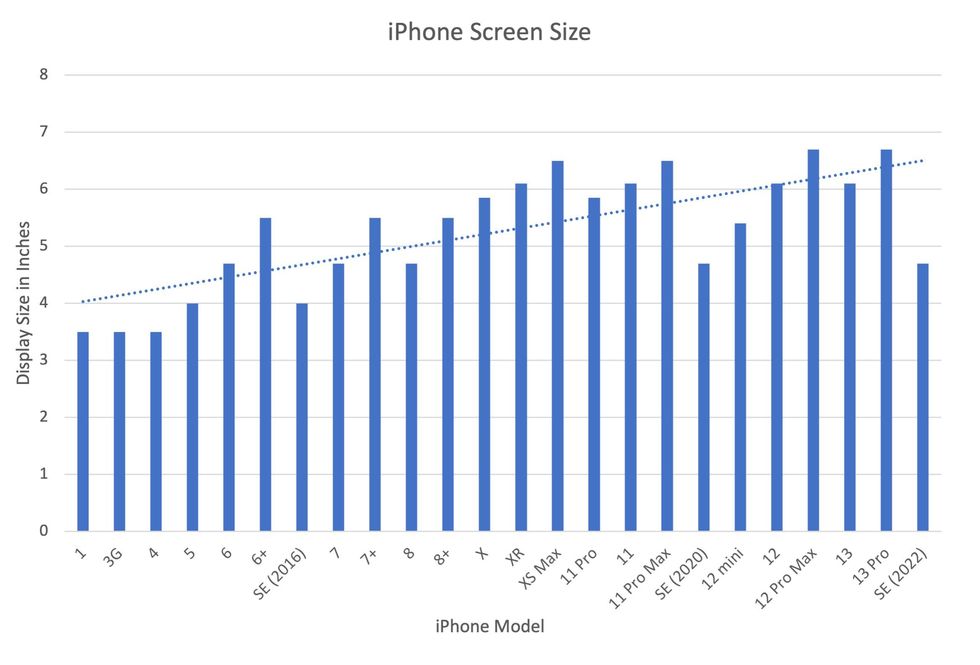

In 2007, the first iPhone measured 3.5-inches diagonally, a measurement known as the display size. That’s been nearly doubled by the newest iPhone 13 Pro, which has a 6.7-inch display. Other phones, too, like the Google Pixel 6 and the Samsung Galaxy S22, have bigger screens than their predecessors. Physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons have had to come up with names for a variety of new conditions: selfie elbow, tech neck, texting thumb. Orthopedic surgeon Sonya Sloan says she sees selfie elbow in younger kids and in women more often than men. She hears complaints related to technology once or twice a day.

The addictive quality of smartphones and social media means that people spend more time on their devices, which exacerbates injuries. According to Statista, 68 percent of those surveyed spent over three hours a day on their phone, and almost half spent five to six hours a day. Another report showed that people dedicate a third of their day to checking their phones, while the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has found that bigger screens, ideal for entertainment purposes, immerse their users more than smaller screens. Oversized screens also provide easier navigation and more space for those with bigger hands or trouble seeing.

But others with conditions like arthritis can benefit from smaller phones. In March of 2016, Apple released the iPhone SE with a display size of 4.7 inches—an inch smaller than the iPhone 7, released that September. Apple has since come out with two more versions of the diminutive iPhone SE, one in 2020 and another in 2022.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance science journalist, has the Google Pixel 6. She was drawn to the phone because Google marketed the Pixel 6’s camera as better at capturing different skin tones. But this phone boasts one of the largest display sizes on the market: 6.4 inches.

Senapathy was diagnosed with carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes in 2017 and fibromyalgia in 2019. She has had to create a curated ergonomic workplace setup, otherwise her wrists and hands get weak and tingly, and she’s had to adjust how she holds her phone to prevent pain flares.

Recently, Senapathy underwent an electromyography, or an EMG, in which doctors insert electrodes into muscles to measure their electrical activity. The electrical response of the muscles tells doctors whether the nerve cells and muscles are successfully communicating. Depending on her results, steroid shots and even surgery might be required. Senapathy wants to stick with her Pixel 6, but the pain she’s experiencing may push her to buy a smaller phone. Unfortunately, options for these modestly sized phones are more limited.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers like Senapathy to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable for creating addictive devices that lead to musculoskeletal injury?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance journalist, bought the Google Pixel 6 because of its high-quality camera, but she’s had to adjust how she holds the oversized phone to prevent pain flares.

Kavin Senapathy

A one-size-fits-all mentality for smartphones will continue to lead to injuries because every user has different wants and needs. S. Shyam Sundar, the founder of Penn State’s lab on media effects and a communications professor, says the needs for mobility and portability conflict with the desire for greater visibility. “The best thing a company can do is offer different sizes,” he says.

Joanna Bryson, an AI ethics expert and professor at The Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of the lack of choice we see comes from the fact that the markets have consolidated so much,” she says. “We want to make sure there’s sufficient diversity [of products].”

Consumers can still maintain some control despite the ubiquity of tech. Sloan, the orthopedic surgeon, has to pester her son to change his body positioning when using his tablet. Our heads get heavier as they bend forward: at rest, they weigh 12 pounds, but bent 60 degrees, they weigh 60. “I have to tell him, ‘Raise your head, son!’” she says. It’s important, Sloan explains, to consider that growth and development will affect ligaments and bones in the neck, potentially making kids even more vulnerable to injuries from misusing gadgets. She recommends that parents limit their kids’ tech time to alleviate strain. She also suggested that tech companies implement a timer to remind us to change our body positioning.

In 2017, Nan-Wei Gong, a former contractor for Google, founded Figur8, which uses wearable trackers to measure muscle function and joint movement. It’s like physical therapy with biofeedback. “Each unique injury has a different biomarker,” says Gong. “With Figur8, you are comparing yourself to yourself.” This allows an individual to self-monitor for wear and tear and strengthen an injury in a way that’s efficient and designed for their body. Gong noticed that the work-from-home model during the COVID-19 pandemic created a new set of ergonomic problems that resulted in injuries. Figur8 provides real-time data for these injuries because “behavioral change requires feedback.”

Gong worked on a project called Jacquard while at Google. Textile experts weave conductive thread into their fabric, and the result is a patch of the fabric—like the cuff of a Levi’s jacket—that responds to commands on your smartphone. One swipe can call your partner or check the weather. It was designed with cyclists in mind who can’t easily check their phones, and it’s part of a growing movement in the tech industry to deliver creative, hands-free design. Gong thinks that engineers at large corporations like Google have accessibility in mind; it’s part of what drives their decisions for new products.

Display sizes of iPhones have become larger over time.

Sourced from Screenrant https://screenrant.com/iphone-apple-release-chronological-order-smartphone/ and Apple Tech Specs: https://www.apple.com/iphone-se/specs/

Back in Germany, Joanna Bryson reminds us that products like smartphones should adhere to best practices. These rules may be especially important for phones and other products with AI that are addictive. Disclosure, accountability, and regulation are important for AI, she says. “The correct balance will keep changing. But we have responsibilities and obligations to each other.” She was on an AI Ethics Council at Google, but the committee was disbanded after only one week due to issues with one of their members.

Bryson was upset about the Council’s dissolution but has faith that other regulatory bodies will prevail. OECD.AI, and international nonprofit, has drafted policies to regulate AI, which countries can sign and implement. “As of July 2021, 46 governments have adhered to the AI principles,” their website reads.

Sundar, the media effects professor, also directs Penn State’s Center for Socially Responsible AI. He says that inclusivity is a crucial aspect of social responsibility and how devices using AI are designed. “We have to go beyond first designing technologies and then making them accessible,” he says. “Instead, we should be considering the issues potentially faced by all different kinds of users before even designing them.”