How Can We Decide If a Biomedical Advance Is Ethical?

A newborn in the maternity ward. (© rufous/Fotolia)

"All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned…"

On July 25, 1978, Louise Brown was born in Oldham, England, the first human born through in vitro fertilization, through the work of Patrick Steptoe, a gynecologist, and Robert Edwards, a physiologist. Her birth was greeted with strong (though not universal) expressions of ethical dismay. Yet in 2016, the latest year for which we have data, nearly two percent of the babies born in the United States – and around the same percentage throughout the developed world – were the result of IVF. Few, if any, think of these children as unnatural, monsters, or freaks or of their parents as anything other than fortunate.

How should we view Dr. He today, knowing that the world's eventual verdict on the ethics of biomedical technologies often changes?

On November 25, 2018, news broke that Chinese scientist, Dr. He Jiankui, claimed to have edited the genomes of embryos, two of whom had recently become the new babies, Lulu and Nana. The response was immediate and overwhelmingly negative.

Times change. So do views. How will Dr. He be viewed in 40 years? And, more importantly, how should we view him today, knowing that the world's eventual verdict on the ethics of biomedical technologies often changes? And when what biomedicine can do changes with vertiginous frequency?

How to determine what is and isn't ethical is above my pay grade. I'm a simple law professor – I can't claim any deeper insight into how to live a moral life than the millennia of religious leaders, philosophers, ethicists, and ordinary people trying to do the right thing. But I can point out some ways to think about these questions that may be helpful.

First, consider two different kinds of ethical commands. Some are quite specific – "thou shalt not kill," for example. Others are more general – two of them are "do unto others as you would have done to you" or "seek the greatest good for the greatest number."

Biomedicine in the last two centuries has often surprised us with new possibilities, situations that cultures, religions, and bodies of ethical thought had not previously had to consider, from vaccination to anesthesia for women in labor to genome editing. Sometimes these possibilities will violate important and deeply accepted precepts for a group or a person. The rise of blood transfusions around World War I created new problems for Jehovah's Witnesses, who believe that the Bible prohibits ingesting blood. The 20th century developments of artificial insemination and IVF both ran afoul of Catholic doctrine prohibiting methods other than "traditional" marital intercourse for conceiving children. If you subscribe to an ethical or moral code that contains prohibitions that modern biomedicine violates, the issue for you is stark – adhere to those beliefs or renounce them.

If the harms seem to outweigh the benefits, it's easy to conclude "this is worrisome."

But many biomedical changes violate no clear moral teachings. Is it ethical or not to edit the DNA of embryos? Not surprisingly, the sacred texts of various religions – few of which were created after, at the latest, the early 19th century, say nothing specific about this. There may be hints, precedents, leanings that could argue one way or another, but no "commandments." In that case, I recommend, at least as a starting point, asking "what are the likely consequences of these actions?"

Will people be, on balance, harmed or helped by them? "Consequentialist" approaches, of various types, are a vast branch of ethical theories. Personally I find a completely consequentialist approach unacceptable – I could not accept, for example, torturing an innocent child even in order to save many lives. But, in the absence of a clear rule, looking at the consequences is a great place to start. If the harms seem to outweigh the benefits, it's easy to conclude "this is worrisome."

Let's use that starting place to look at a few bioethical issues. IVF, for example, once proven (relatively) safe seems to harm no one and to help many, notably the more than 8 million children worldwide born through IVF since 1978 – and their 16 million parents. On the other hand, giving unknowing, and unconsenting, intellectually disabled children hepatitis A harmed them, for an uncertain gain for science. And freezing the heads of the dead seems unlikely to harm anyone alive (except financially) but it also seems almost certain not to benefit anyone. (Those frozen dead heads are not coming back to life.)

Now let's look at two different kinds of biomedical advances. Some are controversial just because they are new; others are controversial because they cut close to the bone – whether or not they violate pre-established ethical or moral norms, they clearly relate to them.

Consider anesthesia during childbirth. When first used, it was controversial. After all, said critics, in Genesis, the Bible says God told Eve, "I will greatly multiply Your pain in childbirth, In pain you will bring forth children." But it did not clearly prohibit pain relief and from the advent of ether on, anesthesia has been common, though not universal, in childbirth in western societies. The pre-existing ethical precepts were not clear and the consequences weighed heavily in favor of anesthesia. Similarly, vaccination seems to violate no deep moral principle. It was, and for some people, still is just strange, and unnatural. The same was true of IVF initially. Opposition to all of these has faded with time and familiarity. It has not disappeared – some people continue to find moral or philosophical problems with "unnatural" childbirth, vaccination, and IVF – but far fewer.

On the other hand, human embryonic stem cell research touches deeper issues. Human embryos are destroyed to make those stem cells. Reasonable people disagree on the moral status of the human embryo, and the moral weight of its destruction, but it does at least bring into play clear and broadly accepted moral precepts, such as "Thou shalt not kill." So, at the far side of an individual's time, does euthanasia. More exposure to, and familiarity with, these practices will not necessarily lead to broad acceptance as the objections involve more than novelty.

The first is "what would I do?" The second – what should my government, culture, religion allow or forbid?

Finally, all this ethical analysis must work at two levels. The first is "what would I do?" The second – what should my government, culture, religion allow or forbid? There are many things I would not do that I don't think should be banned – because I think other people may reasonably have different views from mine. I would not get cosmetic surgery, but I would not ban it – and will try not to think ill of those who choose it

So, how should we assess the ethics of new biomedical procedures when we know that society's views may change? More specifically, what should we think of He Jiankui's experiment with human babies?

First, look to see whether the procedure in question violates, at least fairly clearly, some rule in your ethical or moral code. If so, your choice may not be difficult. But if the procedure is unmentioned in your moral code, probably because it was inconceivable to the code's creators, examine the consequences of the act.

If the procedure is just novel, and not something that touches on important moral concerns, looking at the likely consequences may be enough for your ethical analysis –though it is always worth remembering that predicting consequences perfectly is impossible and predicting them well is never certain. If it does touch on morally significant issues, you need to think those issues through. The consequences may be important to your conclusions but they may not be determinative.

And, then, if you conclude that it is not ethical from your perspective, you need to take yet another step and consider whether it should be banned for people who do not share your perspective. Sometimes the answer will be yes – that psychopaths may not view murder as immoral does not mean we have to let them kill – but sometimes it will be no.

What does this say about He Jiankui's experiment? I have no qualms in condemning it, unequivocally. The potential risks to the babies grossly outweighed any benefits to them, and to science. And his secret work, against a near universal scientific consensus, privileged his own ethical conclusions without giving anyone else a vote, or even a voice.

But if, in ten or twenty years, genome editing of human embryos is shown to be safe (enough) and it is proposed to be used for good reasons – say, to relieve human suffering that could not be treated in other good ways – and with good consents from those directly involved as well as from the relevant society and government – my answer might well change. Yours may not. Bioethics is a process for approaching questions; it is not a set of universal answers.

This article opened with a quotation from the 1848 Communist Manifesto, referring to the dizzying pace of change from industrialization and modernity. You don't need to be a Marxist to appreciate that sentiment. Change – especially in the biosciences – keeps accelerating. How should we assess the ethics of new biotechnologies? The best we can, with what we know, at the time we inhabit. And, in the face of vast uncertainty, with humility.

Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

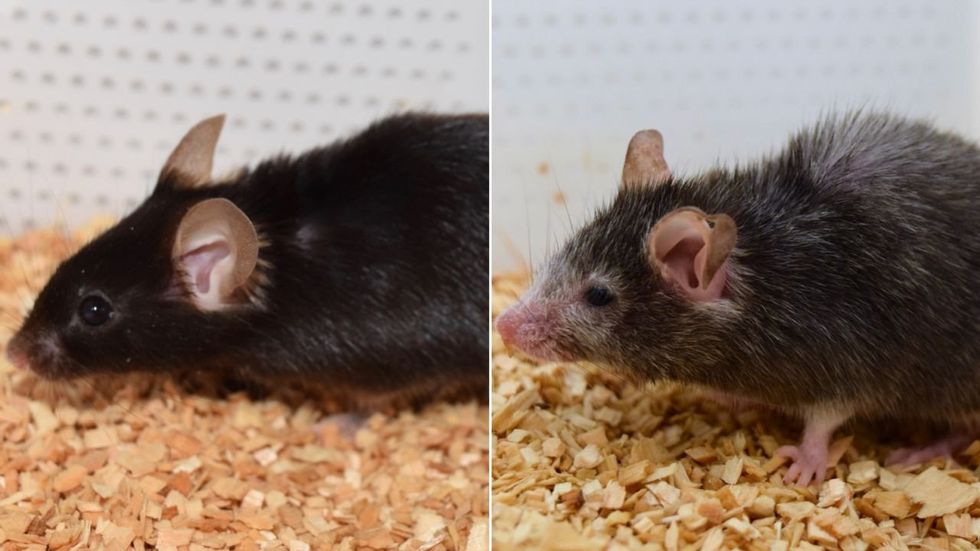

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School