I'm a Healthy Young Woman: Here's Why I Would Get Tested for Alzheimer's Now

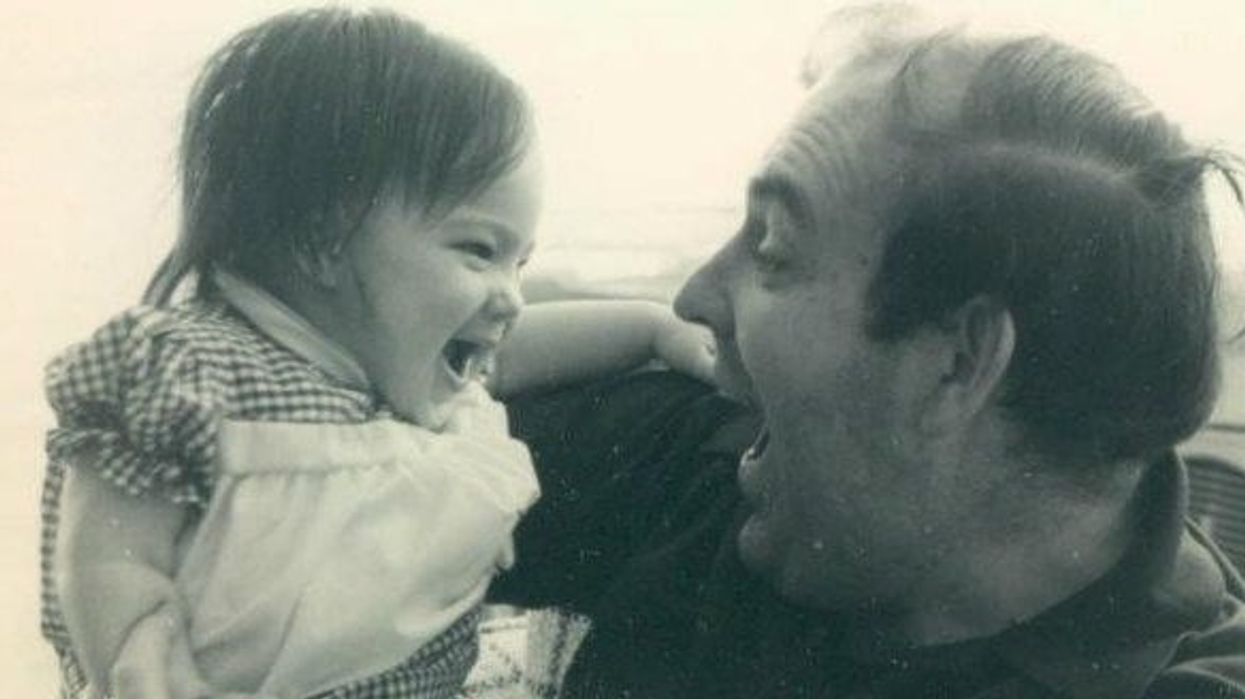

The author as a child with her father in 1981, before he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's.

Editor's Note: A team of researchers in Italy recently used artificial intelligence and machine learning to diagnose Alzheimer's disease on a brain scan an entire decade before symptoms show up in the patient. While some people argue that early detection is critical, others believe the knowledge would do more harm than good. LeapsMag invited contributors with opposite opinions to share their perspectives.

Alzheimer's doesn't run in my family. When my father was diagnosed at the age of 58, we looked at his familial history. Both his parents lived into their late 80's. All of their surviving siblings were similarly long-lived and none had had Alzheimer's or any related dementias. My dad had spent 20 years working for the United Nations in the 60's and 70's in Africa. He was convinced that the Alzheimer's had come from his time spent in dodgy mines where he was exposed without the proper protections to all kinds of chemical processes.

Maybe that was true. Maybe it wasn't. The theory that metals, particularly aluminum, is an environmental factor leading to Alzheimer's has been around for a while. It's mostly been debunked, but clearly something is causing this epidemic as the vast majority of the cases in the world today are age-related. But no one knows what the trigger is, nor are we close to knowing.

If my father had had the Alzheimer's gene, I would go get myself checked for it. If some new MRI were commercially available to scan my brain and let me know if I was developing Alzheimer's, I would also take that test. There are four reasons why.

First, studies have shown that lifestyle has a major impact on the disease. I already run three miles a day. I eat relatively healthily. But like anyone, I don't live strictly on boiled chicken and broccoli. And I definitely enjoy a glass of wine or two. If I knew I had a propensity for the disease, or was developing it, I would be more diligent. I would eat my broccoli and cut out my wine. Life would be less fun, but I'd get more life and that's what's important.

The last picture taken of the author with her father before his death, in 2015.

Secondly, I would also have time to create an end-of-life plan the way my father did not. He told me repeatedly early on in his diagnosis that he did not want to live when he no longer knew me, when he became a burden, when he couldn't feed or bathe himself. I did my best in his final years to help him die quicker: I know that was what he wanted. But, given U.S. laws, all that meant was taking him off his heart and stroke medications and letting him eat anything he wanted, no matter how unhealthy. Knowing what's to come, having seen him go through it, I might consider moving to Belgium, which has begun to allow assisted suicide of those living with Alzheimer's and dementia if they can clearly state their intentions early on in the disease when they still have clarity of mind.

Next, I could help. Right now, there are dozens of Alzheimer's and dementia studies in the works. They are short thousands of willing test subjects. One of the top barriers to learning what's triggering the disease, and finding a cure, is populating these studies. So, knowing would make me a stronger candidate and would potentially help others down the road.

Finally, it would change my priorities. My father died the longest death possible: he succumbed last year more than 15 years after his diagnosis. My mother died the quickest possible way: she had a stress-related brain aneurysm 10 years after my father's diagnosis. Caring for him was too much for her and aneurysms ran in her family; her mother died of one as well. I already get a scan once every five years to see if I'm developing a brain aneurysm. If I am, odds are only 66% that they can operate on it—some aneurysms develop much too deep in the brain to operate, like my mother's.

Would she have wanted to know? Even though the aneurysm in her case was inoperable? I'm not sure. But I imagine if she had known, she would've lived her final years differently. She might have taken that trip to Alaska that she debated but thought was too expensive. She might have gotten organized earlier to make out a will so I wasn't left with chaos in the wake of her death; we'd planned for my father's death, knowing he was ill, but not my mother's. And she might have finally gotten around to dictating her story to me, as she'd always promised me she would when she found the time.

Telling my father's story at the end of his life helped his care.

With my startup MemoryWell, I spend my life now collecting senior stories before they are lost, in part because telling my father's story at the end of his life helped his care. But it's also in part for the story I lost with my mother.

If I knew that my time was limited, I'd not worry so much about saving for retirement. I'd make progress on my bucket list: hike Machu Picchu, scuba dive the Maldives, or raft the Grand Canyon. I'd tell my loved ones as much as I can in my time remaining how much they mean to me. And I would spend more time writing my own story to pass it down—finally finishing the book I've been working on. Maybe it's the writer in me, or maybe it's that I don't have kids of my own yet to carry on a legacy, but I'd want my story to be known, to have others learn from my experiences. And that's the biggest gift knowing would give me.

Editor's Note: Consider the other side of the argument here.

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.