Is Finding Out Your Baby’s Genetics A New Responsibility of Parenting?

A doctor pricks the heel of a newborn for a blood test.

Hours after a baby is born, its heel is pricked with a lancet. Drops of the infant's blood are collected on a porous card, which is then mailed to a state laboratory. The dried blood spots are screened for around thirty conditions, including phenylketonuria (PKU), the metabolic disorder that kick-started this kind of newborn screening over 60 years ago. In the U.S., parents are not asked for permission to screen their child. Newborn screening programs are public health programs, and the assumption is that no good parent would refuse a screening test that could identify a serious yet treatable condition in their baby.

Learning as much as you can about your child's health might seem like a natural obligation of parenting. But it's an assumption that I think needs to be much more closely examined.

Today, with the introduction of genome sequencing into clinical medicine, some are asking whether newborn screening goes far enough. As the cost of sequencing falls, should parents take a more expansive look at their children's health, learning not just whether they have a rare but treatable childhood condition, but also whether they are at risk for untreatable conditions or for diseases that, if they occur at all, will strike only in adulthood? Should genome sequencing be a part of every newborn's care?

It's an idea that appeals to Anne Wojcicki, the founder and CEO of the direct-to-consumer genetic testing company 23andMe, who in a 2016 interview with The Guardian newspaper predicted that having newborns tested would soon be considered standard practice—"as critical as testing your cholesterol"—and a new responsibility of parenting. Wojcicki isn't the only one excited to see everyone's genes examined at birth. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health and perhaps the most prominent advocate of genomics in the United States, has written that he is "almost certain … that whole-genome sequencing will become part of new-born screening in the next few years." Whether that would happen through state-mandated screening programs, or as part of routine pediatric care—or perhaps as a direct-to-consumer service that parents purchase at birth or receive as a baby-shower gift—is not clear.

Learning as much as you can about your child's health might seem like a natural obligation of parenting. But it's an assumption that I think needs to be much more closely examined, both because the results that genome sequencing can return are more complex and more uncertain than one might expect, and because parents are not actually responsible for their child's lifelong health and well-being.

What is a parent supposed to do about such a risk except worry?

Existing newborn screening tests look for the presence of rare conditions that, if identified early in life, before the child shows any symptoms, can be effectively treated. Sequencing could identify many of these same kinds of conditions (and it might be a good tool if it could be targeted to those conditions alone), but it would also identify gene variants that confer an increased risk rather than a certainty of disease. Occasionally that increased risk will be significant. About 12 percent of women in the general population will develop breast cancer during their lives, while those who have a harmful BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene variant have around a 70 percent chance of developing the disease. But for many—perhaps most—conditions, the increased risk associated with a particular gene variant will be very small. Researchers have identified over 600 genes that appear to be associated with schizophrenia, for example, but any one of those confers only a tiny increase in risk for the disorder. What is a parent supposed to do about such a risk except worry?

Sequencing results are uncertain in other important ways as well. While we now have the ability to map the genome—to create a read-out of the pairs of genetic letters that make up a person's DNA—we are still learning what most of it means for a person's health and well-being. Researchers even have a name for gene variants they think might be associated with a disease or disorder, but for which they don't have enough evidence to be sure. They are called "variants of unknown (or uncertain) significance (VUS), and they pop up in most people's sequencing results. In cancer genetics, where much research has been done, about 1 in 5 gene variants are reclassified over time. Most are downgraded, which means that a good number of VUS are eventually designated benign.

While one parent might reasonably decide to learn about their child's risk for a condition about which nothing can be done medically, a different, yet still thoroughly reasonable, parent might prefer to remain ignorant so that they can enjoy the time before their child is afflicted.

Then there's the puzzle of what to do about results that show increased risk or even certainty for a condition that we have no idea how to prevent. Some genomics advocates argue that even if a result is not "medically actionable," it might have "personal utility" because it allows parents to plan for their child's future needs, to enroll them in research, or to connect with other families whose children carry the same genetic marker.

Finding a certain gene variant in one child might inform parents' decisions about whether to have another—and if they do, about whether to use reproductive technologies or prenatal testing to select against that variant in a future child. I have no doubt that for some parents these personal utility arguments are persuasive, but notice how far we've now strayed from the serious yet treatable conditions that motivated governments to set up newborn screening programs, and to mandate such testing for all.

Which brings me to the other problem with the call for sequencing newborn babies: the idea that even if it's not what the law requires, it's what good parents should do. That idea is very compelling when we're talking about sequencing results that show a serious threat to the child's health, especially when interventions are available to prevent or treat that condition. But as I have shown, many sequencing results are not of this type.

While one parent might reasonably decide to learn about their child's risk for a condition about which nothing can be done medically, a different, yet still thoroughly reasonable, parent might prefer to remain ignorant so that they can enjoy the time before their child is afflicted. This parent might decide that the worry—and the hypervigilence it could inspire in them—is not in their child's best interest, or indeed in their own. This parent might also think that it should be up to the child, when he or she is older, to decide whether to learn about his or her risk for adult-onset conditions, especially given that many adults at high familial risk for conditions like Alzheimer's or Huntington's disease choose never to be tested. This parent will value the child's future autonomy and right not to know more than they value the chance to prepare for a health risk that won't strike the child until 40 or 50 years in the future.

Parents are not obligated to learn about their children's risk for a condition that cannot be prevented, has a small risk of occurring, or that would appear only in adulthood.

Contemporary understandings of parenting are famously demanding. We are asked to do everything within our power to advance our children's health and well-being—to act always in our children's best interests. Against that backdrop, the need to sequence every newborn baby's genome might seem obvious. But we should be skeptical. Many sequencing results are complex and uncertain. Parents are not obligated to learn about their children's risk for a condition that cannot be prevented, has a small risk of occurring, or that would appear only in adulthood. To suggest otherwise is to stretch parental responsibilities beyond the realm of childhood and beyond factors that parents can control.

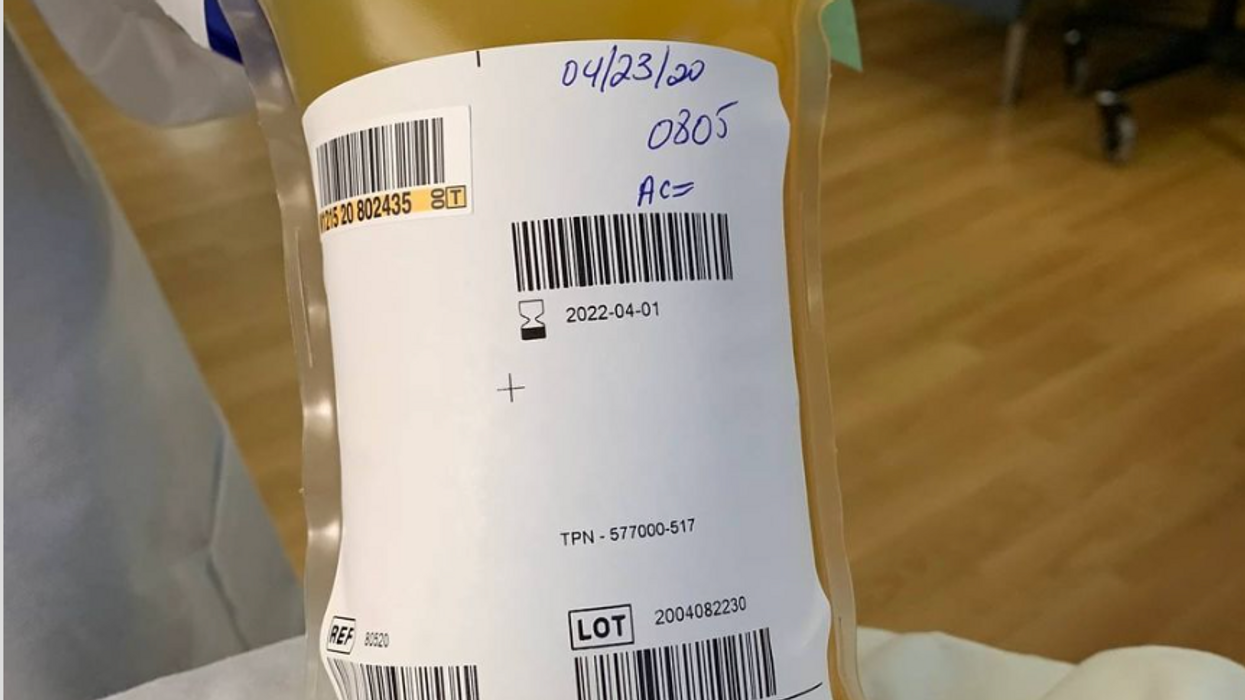

Blood Money: Paying for Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19

A bag of plasma that Tom Hanks donated back in April 2020 after his coronavirus infection. (He was not paid to donate.)

Convalescent plasma – first used to treat diphtheria in 1890 – has been dusted off the shelf to treat COVID-19. Does it work? Should we rely strictly on the altruism of donors or should people be paid for it?

The biologic theory is that a person who has recovered from a disease has chemicals in their blood, most likely antibodies, that contributed to their recovery, and transferring those to a person who is sick might aid their recovery. Whole blood won't work because there are too few antibodies in a single unit of blood and the body can hold only so much of it.

Plasma comprises about 55 percent of whole blood and is what's left once you take out the red blood cells that carry oxygen and the white blood cells of the immune system. Most of it is water but the rest is a complex mix of fats, salts, signaling molecules and proteins produced by the immune system, including antibodies.

A process called apheresis circulates the donors' blood through a machine that separates out the desired parts of blood and returns the rest to the donor. It takes several times the length of a regular whole blood donation to cycle through enough blood for the process. The end product is a yellowish concentration called convalescent plasma.

Recent History

It was used extensively during the great influenza epidemic off 1918 but fell out of favor with the development of antibiotics. Still, whenever a new disease emerges – SARS, MERS, Ebola, even antibiotic-resistant bacteria – doctors turn to convalescent plasma, often as a stopgap until more effective antibiotic and antiviral drugs are developed. The process is certainly safe when standard procedures for handling blood products are followed, and historically it does seem to be beneficial in at least some patients if administered early enough in the disease.

With few good treatment options for COVID-19, doctors have given convalescent plasma to more than a hundred thousand Americans and tens of thousand of people elsewhere, to mixed results. Placebo-controlled trials could give a clearer picture of plasma's value but it is difficult to enroll patients facing possible death when the flip of a coin will determine who will receive a saline solution or plasma.

And the plasma itself isn't some uniform pill stamped out in a factory, it's a natural product that is shaped by the immune history of the donor's body and its encounter not just with SARS-CoV-2 but a lifetime of exposure to different pathogens.

Researchers believe antibodies in plasma are a key factor in directly fighting the virus. But the variety and quantity of antibodies vary from donor to donor, and even over time from the same donor because once the immune system has cleared the virus from the body, it stops putting out antibodies to fight the virus. Often the quality and quantity of antibodies being given to a patient are not measured, making it somewhat hit or miss, which is why several companies have recently developed monoclonal antibodies, a single type of antibody found in blood that is effective against SARS-CoV-2 and that is multiplied in the lab for use as therapy.

Plasma may also contain other unknown factors that contribute to fighting disease, say perhaps signaling molecules that affect gene expression, which might affect the movement of immune cells, their production of antiviral molecules, or the regulation of inflammation. The complexity and lack of standardization makes it difficult to evaluate what might be working or not with a convalescent plasma treatment. Thus researchers are left with few clues about how to make it more effective.

Industrializing Plasma

Many Americans living along the border with Mexico regularly head south to purchase prescription drugs at a significant discount. Less known is the medical traffic the other way, Mexicans who regularly head north to be paid for plasma donations, which are prohibited in their country; the U.S. allows payment for plasma donations but not whole blood. A typical payment is about $35 for a donation but the sudden demand for convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19 commands a premium price, sometimes as high as $200. These donors are part of a fast-growing plasma industry that surpassed $25 billion in 2018. The U.S. supplies about three-quarters of the world's needs for plasma.

Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free.

The pharmaceutical industry has shied away from natural products they cannot patent but they have identified simpler components from plasma, such as clotting factors and immunoglobulins, that have been turned into useful drugs from this raw material of plasma. While some companies have retooled to provide convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19, often paying those donors who have recovered a premium of several times the normal rate, most convalescent plasma has come as donations through traditional blood centers.

In April the Mayo Clinic, in cooperation with the FDA, created an expanded access program for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. It was meant to reduce the paperwork associated with gaining access to a treatment not yet approved by the FDA for that disease. Initially it was supposed to be for 5000 units but it quickly grew to more than twenty times that size. Michael Joyner, the head of the program, discussed that experience in an extended interview in September.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also created associated reimbursement codes, which became permanent in August.

Mayo published an analysis of the first 35,000 patients as a preprint in August. It concluded, "The relationships between mortality and both time to plasma transfusion, and antibody levels provide a signature that is consistent with efficacy for the use of convalescent plasma in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients."

It seemed to work best when given early in infection and in larger doses; a similar pattern has been seen in studies of monoclonal antibodies. A revised version will soon be published in a major medical journal. Some criticized the findings as not being from a randomized clinical trial.

Convalescent plasma is not the only intervention that seems to work better when used earlier in the course of disease. Recently the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly stopped a clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody in hospitalized COVID-19 patients when it became apparent it wasn't helping. It is continuing trials for patients who are less sick and begin treatment earlier, as well as in persons who have been exposed to the virus but not yet diagnosed as infected, to see if it might prevent infection. In November the FDA eased access to this drug outside of clinical trials, though it is not yet approved for sale.

Show Me the Money

The antibodies that seem to give plasma its curative powers are fragile proteins that the body produces to fight the virus. Production shuts down once the virus is cleared and the remaining antibodies survive only for a few weeks before the levels fade. [Vaccines are used to train immune cells to produce antibodies and other defenses to respond to exposure to future pathogens.] So they can be usefully harvested from a recovered patient for only a few short weeks or months before they decline precipitously. The question becomes, how does one mobilize this resource in that short window of opportunity?

The program run by the Mayo Clinic explains the process and criteria for donating convalescent plasma for COVID-19, as well as links to local blood centers equipped to handle those free donations. Commercial plasma centers also are advertising and paying for donations.

A majority of countries prohibit paying donors for blood or blood products, including India. But an investigation by India Today touted a black market of people willing to donate convalescent plasma for the equivalent of several hundred dollars. Officials vowed to prosecute, saying donations should be selfless.

But that enforcement threat seemed to be undercut when the health minister of the state of Assam declared "plasma donors will get preference in several government schemes including the government job interview." It appeared to be a form of compensation that far surpassed simple cash.

The small city of Rexburg, Idaho, with a population a bit over 50,000, overwhelmingly Mormon and home to a campus of Brigham Young University, at one point had one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19 in the current wave of infection. Rumors circulated that some students were intentionally trying to become infected so they could later sell their plasma for top dollar, potentially as much as $200 a visit.

Troubled university officials investigated the allegations but could come up with nothing definitive; how does one prove intentionality with such an omnipresent yet elusive virus? They chalked it up to idle chatter, perhaps an urban legend, which might be associated with alcohol use on some other campus.

Doctors, hospitals, and drug companies are all rightly praised for their altruism in the fight against COVID-19, but they also get paid. Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free. "Why do we expect the donors [of convalescent plasma] to be the only uncompensated people in the process? It really makes no sense," argues Mark Yarborough, an ethicist at the UC Davis School of Medicine in Sacramento.

"When I was in grad school, two of my closest friends, at least once a week they went and gave plasma. That was their weekend spending money," Yarborough recalls. He says upper and middle-income people may have the luxury of donating blood products but prohibiting people from selling their plasma is a bit paternalistic and doesn't do anything to improve the economic status of poor people.

"Asking people to dedicate two hours a week for an entire year in exchange for cookies and milk is demonstrably asking too much," says Peter Jaworski, an ethicist who teaches at Georgetown University.

He notes that companies that pay plasma donors have much lower total costs than do operations that rely solely on uncompensated donations. The companies have to spend less to recruit and retain donors because they increase payments to encourage regular repeat donations. They are able to more rationally schedule visits to maximize use of expensive apheresis equipment and medical personnel used for the collection.

It seems that COVID-19 has been with us forever, but in reality it is less than a year. We have learned much over that short time, can now better manage the disease, and have lower mortality rates to prove it. Just how much convalescent plasma may have contributed to that remains an open question. Access to vaccines is months away for many people, and even then some people will continue to get sick. Given the lack of proven treatments, it makes sense to keep plasma as part of the mix, and not close the door to any legitimate means to obtain it.

Vaccines Without Vaccinations Won’t End the Pandemic

In this 2020 photograph, a bandage is placed on a patient who has just received a vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccine development has advanced at a record-setting pace, thanks to our nation's longstanding support for basic vaccine science coupled with massive public and private sector investments.

Yet, policymakers aren't according anywhere near the same level of priority to investments in the social, behavioral, and data science needed to better understand who and what influences vaccination decision-making. "If we want to be sure vaccines become vaccinations, this is exactly the kind of work that's urgently needed," says Dr. Bruce Gellin, President of Global Immunization at the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

Simply put: it's possible vaccines will remain in refrigerators and not be delivered to the arms of rolled-up sleeves if we don't quickly ramp up vaccine confidence research and broadly disseminate the findings.

According to the most recent Gallup poll, the share of U.S. adults who say they would get a COVID-19 vaccine rose to 58 percent this month from 50 percent in September, with non-white Americans and those ages 45-65 even less willing to be vaccinated. While there is still much we don't understand about COVID-19, we do know that without high levels of immunity in the population, a return to some semblance of normalcy is wishful thinking.

Research from prior vaccination campaigns such as H1N1, HPV, and the annual flu points us in the right direction. Key components of successful vaccination efforts require 1) Identifying the concerns of particular segments of the population; 2) Tailoring messages and incentives to address those concerns, and 3) Reaching out through trusted sources – health care providers, public health departments, and others in the community.

Research during the H1N1 flu found preparing people for some uncertainty actually improved trust, according to Dr. Sandra Crouse Quinn, professor and chair, Family Science, University of Maryland. Dr. Crouse Quinn's research during that period also underscored the need to address the specific vaccine concerns of racial and ethnic groups.

The stunning scientific achievement of COVID-19 vaccines anticipated to be ready in record time needs to be backed up by an equally ambitious and evidence-based effort to build the public's confidence in the vaccines.

Data science has provided crucial insight about the social media universe. Dr. Neil Johnson, a scientist at George Washington University, found that despite having fewer followers, anti-vaccination pages are more numerous and growing faster than pro-vaccination pages. They are more often linked to in discussions on other Facebook pages – such as school parent associations – where people are undecided about vaccination.

We've learned about building vaccine confidence from earlier campaigns. Now, however, we are faced with a unique and challenging set of obstacles to unpack quickly: How do we communicate the importance of eventual COVID-19 vaccines to Americans in light of the muddled-to-poor messaging from political leaders, the weaponizing of relatively simple public health recommendations, the enormous disproportionate toll on people of color, and the torrent of online misinformation? We urgently need data reflective of today's circumstances along with the policy to ensure it is quickly and effectively disseminated to the public health and clinical workforce.

Last year prompted in part by the measles outbreaks, Reps. Michael C. Burgess (R-TX) and Kim Shrier (D-WA), both physicians, introduced the bipartisan Vaccines Act to develop a national surveillance system to monitor vaccination rates and conduct a national campaign to increase awareness of the importance of vaccines. Unfortunately, that legislation wasn't passed. In response to COVID-19, Senate HELP Committee Ranking member Patty Murray (D-WA) has sought funds to strengthen vaccine confidence and combat misinformation with federally supported communication, research, and outreach efforts. Leading experts outside of Congress have called for this type of research, including the Sabin-Aspen Vaccine Science Policy Institute. Most recently, the National Academy of Sciences, in its report regarding the equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine, included as one of its recommendations the need for "a rapid-response program to advance the science behind vaccine confidence."

Addressing trust in vaccination has never been as challenging nor as consequential. The stunning scientific achievement of COVID-19 vaccines anticipated to be ready in record time needs to be backed up by an equally ambitious and evidence-based effort to build the public's confidence in the vaccines. In its remaining days, the Trump Administration should invest in building vaccine confidence with current resources, targeting efforts to ensure COVID vaccines reduce rather than exacerbate racial and ethnic health disparities. Congress must also act to provide the additional research and outreach resources needed as well as pass the Vaccines Act so we are better prepared in the future.

If we don't succeed, COVID-19 will continue wreaking havoc on our health, our society, and our economy. We will also permanently jeopardize public trust in vaccines – one of the most successful medical interventions in human history.