Scientists experiment with burning iron as a fuel source

Sparklers produce a beautiful display of light and heat by burning metal dust, which contains iron. The recent work of Canadian and Dutch researchers suggests we can use iron as a cheap, carbon-free fuel.

Story by Freethink

Try burning an iron metal ingot and you’ll have to wait a long time — but grind it into a powder and it will readily burst into flames. That’s how sparklers work: metal dust burning in a beautiful display of light and heat. But could we burn iron for more than fun? Could this simple material become a cheap, clean, carbon-free fuel?

In new experiments — conducted on rockets, in microgravity — Canadian and Dutch researchers are looking at ways of boosting the efficiency of burning iron, with a view to turning this abundant material — the fourth most common in the Earth’s crust, about about 5% of its mass — into an alternative energy source.

Iron as a fuel

Iron is abundantly available and cheap. More importantly, the byproduct of burning iron is rust (iron oxide), a solid material that is easy to collect and recycle. Neither burning iron nor converting its oxide back produces any carbon in the process.

Iron oxide is potentially renewable by reacting with electricity or hydrogen to become iron again.

Iron has a high energy density: it requires almost the same volume as gasoline to produce the same amount of energy. However, iron has poor specific energy: it’s a lot heavier than gas to produce the same amount of energy. (Think of picking up a jug of gasoline, and then imagine trying to pick up a similar sized chunk of iron.) Therefore, its weight is prohibitive for many applications. Burning iron to run a car isn’t very practical if the iron fuel weighs as much as the car itself.

In its powdered form, however, iron offers more promise as a high-density energy carrier or storage system. Iron-burning furnaces could provide direct heat for industry, home heating, or to generate electricity.

Plus, iron oxide is potentially renewable by reacting with electricity or hydrogen to become iron again (as long as you’ve got a source of clean electricity or green hydrogen). When there’s excess electricity available from renewables like solar and wind, for example, rust could be converted back into iron powder, and then burned on demand to release that energy again.

However, these methods of recycling rust are very energy intensive and inefficient, currently, so improvements to the efficiency of burning iron itself may be crucial to making such a circular system viable.

The science of discrete burning

Powdered particles have a high surface area to volume ratio, which means it is easier to ignite them. This is true for metals as well.

Under the right circumstances, powdered iron can burn in a manner known as discrete burning. In its most ideal form, the flame completely consumes one particle before the heat radiating from it combusts other particles in its vicinity. By studying this process, researchers can better understand and model how iron combusts, allowing them to design better iron-burning furnaces.

Discrete burning is difficult to achieve on Earth. Perfect discrete burning requires a specific particle density and oxygen concentration. When the particles are too close and compacted, the fire jumps to neighboring particles before fully consuming a particle, resulting in a more chaotic and less controlled burn.

Presently, the rate at which powdered iron particles burn or how they release heat in different conditions is poorly understood. This hinders the development of technologies to efficiently utilize iron as a large-scale fuel.

Burning metal in microgravity

In April, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a suborbital “sounding” rocket, carrying three experimental setups. As the rocket traced its parabolic trajectory through the atmosphere, the experiments got a few minutes in free fall, simulating microgravity.

One of the experiments on this mission studied how iron powder burns in the absence of gravity.

In microgravity, particles float in a more uniformly distributed cloud. This allows researchers to model the flow of iron particles and how a flame propagates through a cloud of iron particles in different oxygen concentrations.

Existing fossil fuel power plants could potentially be retrofitted to run on iron fuel.

Insights into how flames propagate through iron powder under different conditions could help design much more efficient iron-burning furnaces.

Clean and carbon-free energy on Earth

Various businesses are looking at ways to incorporate iron fuels into their processes. In particular, it could serve as a cleaner way to supply industrial heat by burning iron to heat water.

For example, Dutch brewery Swinkels Family Brewers, in collaboration with the Eindhoven University of Technology, switched to iron fuel as the heat source to power its brewing process, accounting for 15 million glasses of beer annually. Dutch startup RIFT is running proof-of-concept iron fuel power plants in Helmond and Arnhem.

As researchers continue to improve the efficiency of burning iron, its applicability will extend to other use cases as well. But is the infrastructure in place for this transition?

Often, the transition to new energy sources is slowed by the need to create new infrastructure to utilize them. Fortunately, this isn’t the case with switching from fossil fuels to iron. Since the ideal temperature to burn iron is similar to that for hydrocarbons, existing fossil fuel power plants could potentially be retrofitted to run on iron fuel.

This article originally appeared on Freethink, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

A company in England has made a test that picks out the compounds from breath that reveal if people have liver disease.

Every year, around two million people worldwide die of liver disease. While some people inherit the disease, it’s most commonly caused by hepatitis, obesity and alcoholism. These underlying conditions kill liver cells, causing scar tissue to form until eventually the liver cannot function properly. Since 1979, deaths due to liver disease have increased by 400 percent.

The sooner the disease is detected, the more effective treatment can be. But once symptoms appear, the liver is already damaged. Around 50 percent of cases are diagnosed only after the disease has reached the final stages, when treatment is largely ineffective.

To address this problem, Owlstone Medical, a biotech company in England, has developed a breath test that can detect liver disease earlier than conventional approaches. Human breath contains volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that change in the first stages of liver disease. Owlstone’s breath test can reliably collect, store and detect VOCs, while picking out the specific compounds that reveal liver disease.

“There’s a need to screen more broadly for people with early-stage liver disease,” says Owlstone’s CEO Billy Boyle. “Equally important is having a test that's non-invasive, cost effective and can be deployed in a primary care setting.”

The standard tool for detection is a biopsy. It is invasive and expensive, making it impractical to use for people who aren't yet symptomatic. Meanwhile, blood tests are less invasive, but they can be inaccurate and can’t discriminate between different stages of the disease.

In the past, breath tests have not been widely used because of the difficulties of reliably collecting and storing breath. But Owlstone’s technology could help change that.

The team is testing patients in the early stages of advanced liver disease, or cirrhosis, to identify and detect these biomarkers. In an initial study, Owlstone’s breathalyzer was able to pick out patients who had early cirrhosis with 83 percent sensitivity.

Boyle’s work is personally motivated. His wife died of colorectal cancer after she was diagnosed with a progressed form of the disease. “That was a big impetus for me to see if this technology could work in early detection,” he says. “As a company, Owlstone is interested in early detection across a range of diseases because we think that's a way to save lives and a way to save costs.”

How it works

In the past, breath tests have not been widely used because of the difficulties of reliably collecting and storing breath. But Owlstone’s technology could help change that.

Study participants breathe into a mouthpiece attached to a breath sampler developed by Owlstone. It has cartridges are designed and optimized to collect gases. The sampler specifically targets VOCs, extracting them from atmospheric gases in breath, to ensure that even low levels of these compounds are captured.

The sampler can store compounds stably before they are assessed through a method called mass spectrometry, in which compounds are converted into charged atoms, before electromagnetic fields filter and identify even the tiniest amounts of charged atoms according to their weight and charge.

The top four compounds in our breath

In an initial study, Owlstone captured VOCs in breath to see which ones could help them tell the difference between people with and without liver disease. They tested the breath of 46 patients with liver disease - most of them in the earlier stages of cirrhosis - and 42 healthy people. Using this data, they were able to create a diagnostic model. Individually, compounds like 2-Pentanone and limonene performed well as markers for liver disease. Owlstone achieved even better performance by examining the levels of the top four compounds together, distinguishing between liver disease cases and controls with 95 percent accuracy.

“It was a good proof of principle since it looks like there are breath biomarkers that can discriminate between diseases,” Boyle says. “That was a bit of a stepping stone for us to say, taking those identified, let’s try and dose with specific concentrations of probes. It's part of building the evidence and steering the clinical trials to get to liver disease sensitivity.”

Sabine Szunerits, a professor of chemistry in Institute of Electronics at the University of Lille, sees the potential of Owlstone’s technology.

“Breath analysis is showing real promise as a clinical diagnostic tool,” says Szunerits, who has no ties with the company. “Owlstone Medical’s technology is extremely effective in collecting small volatile organic biomarkers in the breath. In combination with pattern recognition it can give an answer on liver disease severity. I see it as a very promising way to give patients novel chances to be cured.”

Improving the breath sampling process

Challenges remain. With more than one thousand VOCs found in the breath, it can be difficult to identify markers for liver disease that are consistent across many patients.

Julian Gardner is a professor of electrical engineering at Warwick University who researches electronic sensing devices. “Everyone’s breath has different levels of VOCs and different ones according to gender, diet, age etc,” Gardner says. “It is indeed very challenging to selectively detect the biomarkers in the breath for liver disease.”

So Owlstone is putting chemicals in the body that they know interact differently with patients with liver disease, and then using the breath sampler to measure these specific VOCs. The chemicals they administer are called Exogenous Volatile Organic Compound) probes, or EVOCs.

Most recently, they used limonene as an EVOC probe, testing 29 patients with early cirrhosis and 29 controls. They gave the limonene to subjects at specific doses to measure how its concentrations change in breath. The aim was to try and see what was happening in their livers.

“They are proposing to use drugs to enhance the signal as they are concerned about the sensitivity and selectivity of their method,” Gardner says. “The approach of EVOC probes is probably necessary as you can then eliminate the person-to-person variation that will be considerable in the soup of VOCs in our breath.”

Through these probes, Owlstone could identify patients with liver disease with 83 percent sensitivity. By targeting what they knew was a disease mechanism, they were able to amplify the signal. The company is starting a larger clinical trial, and the plan is to eventually use a panel of EVOC probes to make sure they can see diverging VOCs more clearly.

“I think the approach of using probes to amplify the VOC signal will ultimately increase the specificity of any VOC breath tests, and improve their practical usability,” says Roger Yazbek, who leads the South Australian Breath Analysis Research (SABAR) laboratory in Flinders University. “Whilst the findings are interesting, it still is only a small cohort of patients in one location.”

The future of breath diagnosis

Owlstone wants to partner with pharmaceutical companies looking to learn if their drugs have an effect on liver disease. They’ve also developed a microchip, a miniaturized version of mass spectrometry instruments, that can be used with the breathalyzer. It is less sensitive but will enable faster detection.

Boyle says the company's mission is for their tests to save 100,000 lives. "There are lots of risks and lots of challenges. I think there's an opportunity to really establish breath as a new diagnostic class.”

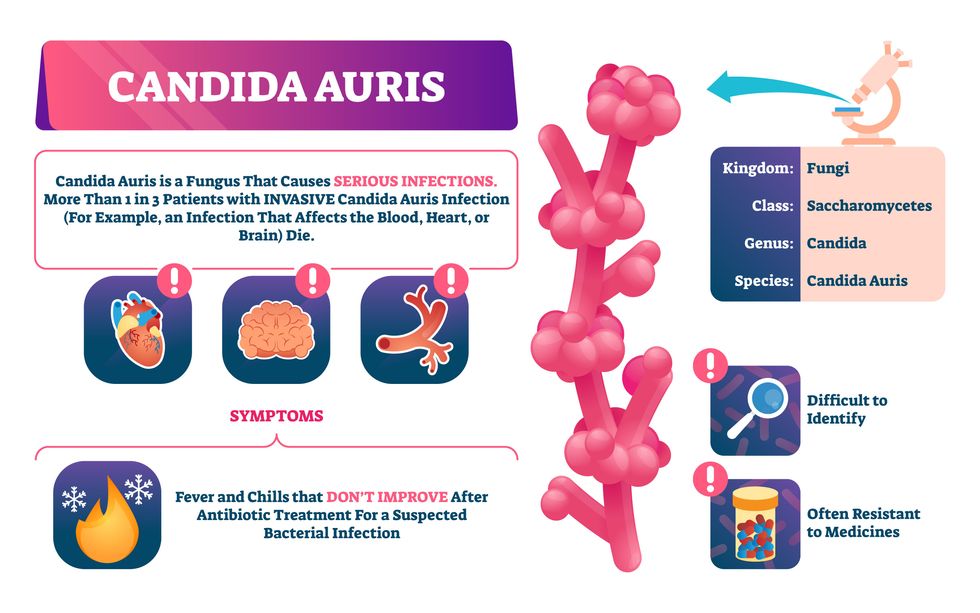

Doctors worry that fungal pathogens may cause the next pandemic.

Bacterial antibiotic resistance has been a concern in the medical field for several years. Now a new, similar threat is arising: drug-resistant fungal infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers antifungal and antimicrobial resistance to be among the world’s greatest public health challenges.

One particular type of fungal infection caused by Candida auris is escalating rapidly throughout the world. And to make matters worse, C. auris is becoming increasingly resistant to current antifungal medications, which means that if you develop a C. auris infection, the drugs your doctor prescribes may not work. “We’re effectively out of medicines,” says Thomas Walsh, founding director of the Center for Innovative Therapeutics and Diagnostics, a translational research center dedicated to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem. Walsh spoke about the challenges at a Demy-Colton Virtual Salon, one in a series of interactive discussions among life science thought leaders.

Although C. auris typically doesn’t sicken healthy people, it afflicts immunocompromised hospital patients and may cause severe infections that can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which the overwhelmed immune system begins to attack the body’s own organs. Between 30 and 60 percent of patients who contract a C. auris infection die from it, according to the CDC. People who are undergoing stem cell transplants, have catheters or have taken antifungal or antibiotic medicines are at highest risk. “We’re coming to a perfect storm of increasing resistance rates, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed patients worldwide and a bug that is adapting to higher temperatures as the climate changes,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the National BioDefense Science Board.

Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures.

Although medical professionals aren’t concerned at this point about C. auris evolving to affect healthy people, they worry that its presence in hospitals can turn routine surgeries into life-threatening calamities. “It’s coming,” says Fernandes. “It’s just a matter of time.”

An emerging global threat

“Fungi are found in the environment,” explains Fernandes, so Candida spores can easily wind up on people’s skin. In hospitals, they can be transferred from contact with healthcare workers or contaminated surfaces. Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures. It can enter the body during medical treatments that break the skin—and cause an infection. Overall, fungal infections cost some $48 billion in the U.S. each year. And infection rates are increasing because, in an ironic twist, advanced medical therapies are enabling severely ill patients to live longer and, therefore, be exposed to this pathogen.

The first-ever case of a C. auris infection was reported in Japan in 2009, although an analysis of Candida samples dated the earliest strain to a 1996 sample from South Korea. Since then, five separate varieties – called clades, which are similar to strains among bacteria – developed independently in different geographies: South Asia, East Asia, South Africa, South America and, recently, Iran. So far, C. auris infections have been reported in 35 countries.

In the U.S., the first infection was reported in 2016, and the CDC started tracking it nationally two years later. During that time, 5,654 cases have been reported to the CDC, which only tracks U.S. data.

What’s more notable than the number of cases is their rate of increase. In 2016, new cases increased by 175 percent and, on average, they have approximately doubled every year. From 2016 through 2022, the number of infections jumped from 63 to 2,377, a roughly 37-fold increase.

“This reminds me of what we saw with epidemics from 2013 through 2020… with Ebola, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Robin Robinson, CEO of Spriovas and founding director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These epidemics started with a hockey stick trajectory, Robinson says—a gradual growth leading to a sharp spike, just like the shape of a hockey stick.

Another challenge is that right now medics don’t have rapid diagnostic tests for fungal infections. Currently, patients are often misdiagnosed because C. auris resembles several other easily treated fungi. Or they are diagnosed long after the infection begins and is harder to treat.

The problem is that existing diagnostics tests can only identify C. auris once it reaches the bloodstream. Yet, because this pathogen infects bodily tissues first, it should be possible to catch it much earlier before it becomes life-threatening. “We have to diagnose it before it reaches the bloodstream,” Walsh says.

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics.

“We need to focus on rapid diagnostic tests that do not rely on a positive blood culture,” says John Sperzel, president and CEO of T2 Biosystems, a company specializing in diagnostics solutions. Blood cultures typically take two to three days for the concentration of Candida to become large enough to detect. The company’s novel test detects about 90 percent of Candida species within three to five hours—thanks to its ability to spot minute quantities of the pathogen in blood samples instead of waiting for them to incubate and proliferate.

Unlike other Candida species C. auris thrives at human body temperatures

Adobe Stock

Tackling the resistance challenge

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics. The number of cases that stopped responding to echinocandin, the first-line therapy for most Candida infections, tripled in 2020, according to a study by the CDC.

Now, each of the first four clades shows varying levels of resistance to all three commonly prescribed classes of antifungal medications, such as azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. For example, 97 percent of infections from C. auris Clade I are resistant to fluconazole, 54 percent to voriconazole and 30 percent of amphotericin. Nearly half are resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. Even with Clade II fungi, which has the least resistance of all the clades, 11 to 14 percent have become resistant to fluconazole.

Anti-fungal therapies typically target specific chemical compounds present on fungi’s cell membranes, but not on human cells—otherwise the medicine would cause damage to our own tissues. Fluconazole and other azole antifungals target a compound called ergosterol, preventing the fungal cells from replicating. Over the years, however, C. auris evolved to resist it, so existing fungal medications don’t work as well anymore.

A newer class of drugs called echinocandins targets a different part of the fungal cell. “The echinocandins – like caspofungin – inhibit (a part of the fungi) involved in making glucan, which is an essential component of the fungal cell wall and is not found in human cells,” Fernandes says. New antifungal treatments are needed, she adds, but there are only a few magic bullets that will hit just the fungus and not the human cells.

Research to fight infections also has been challenged by a lack of government support. That is changing now that BARDA is requesting proposals to develop novel antifungals. “The scope includes C. auris, as well as antifungals following a radiological/nuclear emergency, says BARDA spokesperson Elleen Kane.

The remaining challenge is the number of patients available to participate in clinical trials. Large numbers are needed, but the available patients are quite sick and often die before trials can be completed. Consequently, few biopharmaceutical companies are developing new treatments for C. auris.

ClinicalTrials.gov reports only two drugs in development for invasive C. auris infections—those than can spread throughout the body rather than localize in one particular area, like throat or vaginal infections: ibrexafungerp by Scynexis, Inc., fosmanogepix, by Pfizer.

Scynexis’ ibrexafungerp appears active against C. auris and other emerging, drug-resistant pathogens. The FDA recently approved it as a therapy for vaginal yeast infections and it is undergoing Phase III clinical trials against invasive candidiasis in an attempt to keep the infection from spreading.

“Ibreafungerp is structurally different from other echinocandins,” Fernandes says, because it targets a different part of the fungus. “We’re lucky it has activity against C. auris.”

Pfizer’s fosmanogepix is in Phase II clinical trials for patients with invasive fungal infections caused by multiple Candida species. Results are showing significantly better survival rates for people taking fosmanogepix.

Although C. auris does pose a serious threat to healthcare worldwide, scientists try to stay optimistic—because they recognized the problem early enough, they might have solutions in place before the perfect storm hits. “There is a bit of hope,” says Robinson. “BARDA has finally been able to fund the development of new antifungal agents and, hopefully, this year we can get several new classes of antifungals into development.”