Scientists forecast new disease outbreaks

A mosquito under the microscope.

Two years, six million deaths and still counting, scientists are searching for answers to prevent another COVID-19-like tragedy from ever occurring again. And it’s a gargantuan task.

Our disturbed ecosystems are creating more favorable conditions for the spread of infectious disease. Global warming, deforestation, rising sea levels and flooding have contributed to a rise in mosquito-borne infections and longer tick seasons. Disease-carrying animals are in closer range to other species and humans as they migrate to escape the heat. Bats are thought to have carried the SARS-CoV-2 virus to Wuhan, either directly or through another host animal, but thousands of novel viruses are lurking within other wild creatures.

Understanding how climate change contributes to the spread of disease is critical in predicting and thwarting future calamities. But the problem is that predictive models aren’t yet where they need to be for forecasting with certainty beyond the next year, as we could for weather, for instance.

The association between climate and infectious disease is poorly understood, says Irina Tezaur, a computational scientist at Sandia National Laboratories. “Correlations have been observed but it’s not known if these correlations translate to causal relationships.”

To make accurate longer-term predictions, scientists need more empirical data, multiple datasets specific to locations and diseases, and the ability to calculate risks that depend on unpredictable nature and human behavior. Another obstacle is that climate scientists and epidemiologists are not collaborating effectively, so some researchers are calling for a multidisciplinary approach, a new field called Outbreak Science.

Climate scientists are far ahead of epidemiologists in gathering essential data.

Earth System Models—combining the interactions of atmosphere, ocean, land, ice and biosphere—have been in place for two decades to monitor the effects of global climate change. These models must be combined with epidemiological and human model research, areas that are easily skewed by unpredictable elements, from extreme weather events to public environmental policy shifts.

“There is never just one driver in tracking the impact of climate on infectious disease,” says Joacim Rocklöv, a professor at the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health & Heidelberg Interdisciplinary Centre for Scientific Computing in Germany. Rocklöv has studied how climate affects vector-borne diseases—those transmitted to humans by mosquitoes, ticks or fleas. “You need to disentangle the variables to find out how much difference climate makes to the outcome and how much is other factors.” Determinants from deforestation to population density to lack of healthcare access influence the spread of disease.

Even though climate change is not the primary driver of infectious disease today, it poses a major threat to public health in the future, says Rocklöv.

The promise of predictive modeling

“Models are simplifications of a system we’re trying to understand,” says Jeremy Hess, who directs the Center for Health and the Global Environment at University of Washington in Seattle. “They’re tools for learning that improve over time with new observations.”

Accurate predictions depend on high-quality, long-term observational data but models must start with assumptions. “It’s not possible to apply an evidence-based approach for the next 40 years,” says Rocklöv. “Using models to experiment and learn is the only way to figure out what climate means for infectious disease. We collect data and analyze what already happened. What we do today will not make a difference for several decades.”

To improve accuracy, scientists develop and draw on thousands of models to cover as many scenarios as possible. One model may capture the dynamics of disease transmission while another focuses on immunity data or ocean influences or seasonal components of a virus. Further, each model needs to be disease-specific and often location-specific to be useful.

“All models have biases so it’s important to use a suite of models,” Tezaur stresses.

The modeling scientist chooses the drivers of change and parameters based on the question explored. The drivers could be increased precipitation, poverty or mosquito prevalence, for instance. Later, the scientist may need to isolate the effect of one driver so that will require another model.

There have been some related successes, such as the latest models for mosquito-borne diseases like Dengue, Zika and malaria as well as those for flu and tick-borne diseases, says Hess.

Rocklöv was part of a research team that used test data from 2018 and 2019 to identify regions at risk for West Nile virus outbreaks. Using AI, scientists were able to forecast outbreaks of the virus for the entire transmission season in Europe. “In the end, we want data-driven models; that’s what AI can accomplish,” says Rocklöv. Other researchers are making an important headway in creating a framework to predict novel host–parasite interactions.

Modeling studies can run months, years or decades. “The scientist is working with layers of data. The challenge is how to transform and couple different models together on a planetary scale,” says Jeanne Fair, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, Biosecurity and Public Health, in New Mexico.

Disease forecasting will require a significant investment into the infrastructure needed to collect data about the environment, vectors, and hosts a tall spatial and temporal resolutions.

And it’s a constantly changing picture. A modeling study in an April 2022 issue of Nature predicted that thousands of animals will migrate to cooler locales as temperatures rise. This means that various species will come into closer contact with people and other mammals for the first time. This is likely to increase the risk of emerging infectious disease transmitted from animals to humans, especially in Africa and Asia.

Other things can happen too. Global warming could precipitate viral mutations or new infectious diseases that don’t respond to antimicrobial treatments. Insecticide-resistant mosquitoes could evolve. Weather-related food insecurity could increase malnutrition and weaken people’s immune systems. And the impact of an epidemic will be worse if it co-occurs during a heatwave, flood, or drought, says Hess.

The devil is in the climate variables

Solid predictions about the future of climate and disease are not possible with so many uncertainties. Difficult-to-measure drivers must be added to the empirical model mix, such as land and water use, ecosystem changes or the public’s willingness to accept a vaccine or practice social distancing. Nor is there any precedent for calculating the effect of climate changes that are accelerating at a faster speed than ever before.

The most critical climate variables thought to influence disease spread are temperature, precipitation, humidity, sunshine and wind, according to Tezaur’s research. And then there are variables within variables. Influenza scientists, for example, found that warm winters were predictors of the most severe flu seasons in the following year.

The human factor may be the most challenging determinant. To what degree will people curtail greenhouse gas emissions, if at all? The swift development of effective COVID-19 vaccines was a game-changer, but will scientists be able to repeat it during the next pandemic? Plus, no model could predict the amount of internet-fueled COVID-19 misinformation, Fair noted. To tackle this issue, infectious disease teams are looking to include more sociologists and political scientists in their modeling.

Addressing the gaps

Currently, researchers are focusing on the near future, predicting for next year, says Fair. “When it comes to long-term, that’s where we have the most work to do.” While scientists cannot foresee how political influences and misinformation spread will affect models, they are positioned to make headway in collecting and assessing new data streams that have never been merged.

Disease forecasting will require a significant investment into the infrastructure needed to collect data about the environment, vectors, and hosts at all spatial and temporal resolutions, Fair and her co-authors stated in their recent study. For example real-time data on mosquito prevalence and diversity in various settings and times is limited or non-existent. Fair also would like to see standards set in mosquito data collection in every country. “Standardizing across the US would be a huge accomplishment,” she says.

Understanding how climate change contributes to the spread of disease is critical for thwarting future calamities.

Jeanne Fair

Hess points to a dearth of data in local and regional datasets about how extreme weather events play out in different geographic locations. His research indicates that Africa and the Middle East experienced substantial climate shifts, for example, but are unrepresented in the evidentiary database, which limits conclusions. “A model for dengue may be good in Singapore but not necessarily in Port-au-Prince,” Hess explains. And, he adds, scientists need a way of evaluating models for how effective they are.

The hope, Rocklöv says, is that in the future we will have data-driven models rather than theoretical ones. In turn, sharper statistical analyses can inform resource allocation and intervention strategies to prevent outbreaks.

Most of all, experts emphasize that epidemiologists and climate scientists must stop working in silos. If scientists can successfully merge epidemiological data with climatic, biological, environmental, ecological and demographic data, they will make better predictions about complex disease patterns. Modeling “cross talk” and among disciplines and, in some cases, refusal to release data between countries is hindering discovery and advances.

It’s time for bold transdisciplinary action, says Hess. He points to initiatives that need funding in disease surveillance and control; developing and testing interventions; community education and social mobilization; decision-support analytics to predict when and where infections will emerge; advanced methodologies to improve modeling; training scientists in data management and integrated surveillance.

Establishing a new field of Outbreak Science to coordinate collaboration would accelerate progress. Investment in decision-support modeling tools for public health teams, policy makers, and other long-term planning stakeholders is imperative, too. We need to invest in programs that encourage people from climate modeling and epidemiology to work together in a cohesive fashion, says Tezaur. Joining forces is the only way to solve the formidable challenges ahead.

This article originally appeared in One Health/One Planet, a single-issue magazine that explores how climate change and other environmental shifts are increasing vulnerabilities to infectious diseases by land and by sea. The magazine probes how scientists are making progress with leaders in other fields toward solutions that embrace diverse perspectives and the interconnectedness of all lifeforms and the planet.

Doctors worry that fungal pathogens may cause the next pandemic.

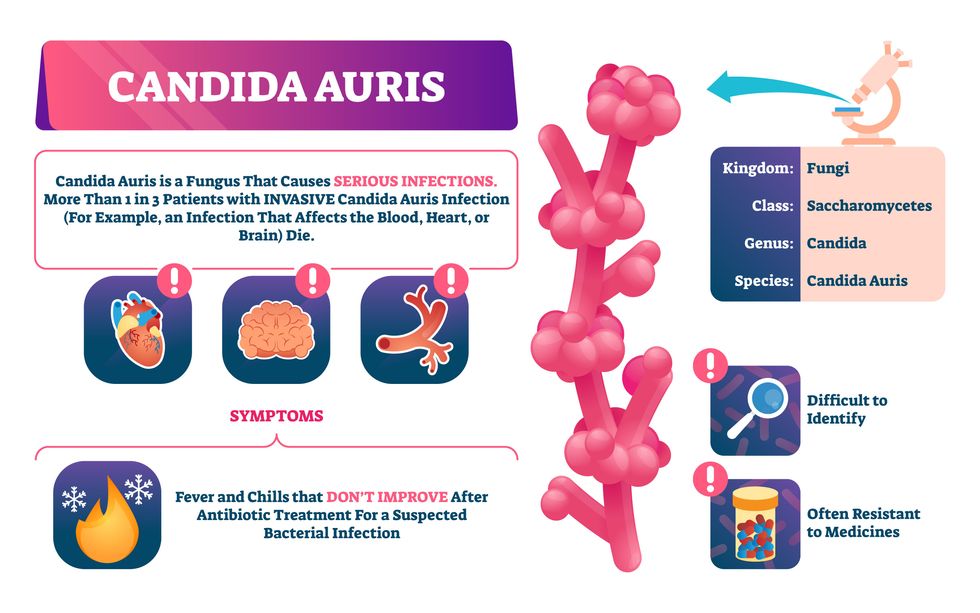

Bacterial antibiotic resistance has been a concern in the medical field for several years. Now a new, similar threat is arising: drug-resistant fungal infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers antifungal and antimicrobial resistance to be among the world’s greatest public health challenges.

One particular type of fungal infection caused by Candida auris is escalating rapidly throughout the world. And to make matters worse, C. auris is becoming increasingly resistant to current antifungal medications, which means that if you develop a C. auris infection, the drugs your doctor prescribes may not work. “We’re effectively out of medicines,” says Thomas Walsh, founding director of the Center for Innovative Therapeutics and Diagnostics, a translational research center dedicated to solving the antimicrobial resistance problem. Walsh spoke about the challenges at a Demy-Colton Virtual Salon, one in a series of interactive discussions among life science thought leaders.

Although C. auris typically doesn’t sicken healthy people, it afflicts immunocompromised hospital patients and may cause severe infections that can lead to sepsis, a life-threatening condition in which the overwhelmed immune system begins to attack the body’s own organs. Between 30 and 60 percent of patients who contract a C. auris infection die from it, according to the CDC. People who are undergoing stem cell transplants, have catheters or have taken antifungal or antibiotic medicines are at highest risk. “We’re coming to a perfect storm of increasing resistance rates, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed patients worldwide and a bug that is adapting to higher temperatures as the climate changes,” says Prabhavathi Fernandes, chair of the National BioDefense Science Board.

Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures.

Although medical professionals aren’t concerned at this point about C. auris evolving to affect healthy people, they worry that its presence in hospitals can turn routine surgeries into life-threatening calamities. “It’s coming,” says Fernandes. “It’s just a matter of time.”

An emerging global threat

“Fungi are found in the environment,” explains Fernandes, so Candida spores can easily wind up on people’s skin. In hospitals, they can be transferred from contact with healthcare workers or contaminated surfaces. Most Candida species aren’t well-adapted to our body temperatures so they aren’t a threat. C. auris, however, thrives at human body temperatures. It can enter the body during medical treatments that break the skin—and cause an infection. Overall, fungal infections cost some $48 billion in the U.S. each year. And infection rates are increasing because, in an ironic twist, advanced medical therapies are enabling severely ill patients to live longer and, therefore, be exposed to this pathogen.

The first-ever case of a C. auris infection was reported in Japan in 2009, although an analysis of Candida samples dated the earliest strain to a 1996 sample from South Korea. Since then, five separate varieties – called clades, which are similar to strains among bacteria – developed independently in different geographies: South Asia, East Asia, South Africa, South America and, recently, Iran. So far, C. auris infections have been reported in 35 countries.

In the U.S., the first infection was reported in 2016, and the CDC started tracking it nationally two years later. During that time, 5,654 cases have been reported to the CDC, which only tracks U.S. data.

What’s more notable than the number of cases is their rate of increase. In 2016, new cases increased by 175 percent and, on average, they have approximately doubled every year. From 2016 through 2022, the number of infections jumped from 63 to 2,377, a roughly 37-fold increase.

“This reminds me of what we saw with epidemics from 2013 through 2020… with Ebola, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Robin Robinson, CEO of Spriovas and founding director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These epidemics started with a hockey stick trajectory, Robinson says—a gradual growth leading to a sharp spike, just like the shape of a hockey stick.

Another challenge is that right now medics don’t have rapid diagnostic tests for fungal infections. Currently, patients are often misdiagnosed because C. auris resembles several other easily treated fungi. Or they are diagnosed long after the infection begins and is harder to treat.

The problem is that existing diagnostics tests can only identify C. auris once it reaches the bloodstream. Yet, because this pathogen infects bodily tissues first, it should be possible to catch it much earlier before it becomes life-threatening. “We have to diagnose it before it reaches the bloodstream,” Walsh says.

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics.

“We need to focus on rapid diagnostic tests that do not rely on a positive blood culture,” says John Sperzel, president and CEO of T2 Biosystems, a company specializing in diagnostics solutions. Blood cultures typically take two to three days for the concentration of Candida to become large enough to detect. The company’s novel test detects about 90 percent of Candida species within three to five hours—thanks to its ability to spot minute quantities of the pathogen in blood samples instead of waiting for them to incubate and proliferate.

Unlike other Candida species C. auris thrives at human body temperatures

Adobe Stock

Tackling the resistance challenge

The most alarming fact is that some Candida infections no longer respond to standard therapeutics. The number of cases that stopped responding to echinocandin, the first-line therapy for most Candida infections, tripled in 2020, according to a study by the CDC.

Now, each of the first four clades shows varying levels of resistance to all three commonly prescribed classes of antifungal medications, such as azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes. For example, 97 percent of infections from C. auris Clade I are resistant to fluconazole, 54 percent to voriconazole and 30 percent of amphotericin. Nearly half are resistant to multiple antifungal drugs. Even with Clade II fungi, which has the least resistance of all the clades, 11 to 14 percent have become resistant to fluconazole.

Anti-fungal therapies typically target specific chemical compounds present on fungi’s cell membranes, but not on human cells—otherwise the medicine would cause damage to our own tissues. Fluconazole and other azole antifungals target a compound called ergosterol, preventing the fungal cells from replicating. Over the years, however, C. auris evolved to resist it, so existing fungal medications don’t work as well anymore.

A newer class of drugs called echinocandins targets a different part of the fungal cell. “The echinocandins – like caspofungin – inhibit (a part of the fungi) involved in making glucan, which is an essential component of the fungal cell wall and is not found in human cells,” Fernandes says. New antifungal treatments are needed, she adds, but there are only a few magic bullets that will hit just the fungus and not the human cells.

Research to fight infections also has been challenged by a lack of government support. That is changing now that BARDA is requesting proposals to develop novel antifungals. “The scope includes C. auris, as well as antifungals following a radiological/nuclear emergency, says BARDA spokesperson Elleen Kane.

The remaining challenge is the number of patients available to participate in clinical trials. Large numbers are needed, but the available patients are quite sick and often die before trials can be completed. Consequently, few biopharmaceutical companies are developing new treatments for C. auris.

ClinicalTrials.gov reports only two drugs in development for invasive C. auris infections—those than can spread throughout the body rather than localize in one particular area, like throat or vaginal infections: ibrexafungerp by Scynexis, Inc., fosmanogepix, by Pfizer.

Scynexis’ ibrexafungerp appears active against C. auris and other emerging, drug-resistant pathogens. The FDA recently approved it as a therapy for vaginal yeast infections and it is undergoing Phase III clinical trials against invasive candidiasis in an attempt to keep the infection from spreading.

“Ibreafungerp is structurally different from other echinocandins,” Fernandes says, because it targets a different part of the fungus. “We’re lucky it has activity against C. auris.”

Pfizer’s fosmanogepix is in Phase II clinical trials for patients with invasive fungal infections caused by multiple Candida species. Results are showing significantly better survival rates for people taking fosmanogepix.

Although C. auris does pose a serious threat to healthcare worldwide, scientists try to stay optimistic—because they recognized the problem early enough, they might have solutions in place before the perfect storm hits. “There is a bit of hope,” says Robinson. “BARDA has finally been able to fund the development of new antifungal agents and, hopefully, this year we can get several new classes of antifungals into development.”

New elevators could lift up our access to space

A space elevator would be cheaper and cleaner than using rockets

Story by Big Think

When people first started exploring space in the 1960s, it cost upwards of $80,000 (adjusted for inflation) to put a single pound of payload into low-Earth orbit.

A major reason for this high cost was the need to build a new, expensive rocket for every launch. That really started to change when SpaceX began making cheap, reusable rockets, and today, the company is ferrying customer payloads to LEO at a price of just $1,300 per pound.

This is making space accessible to scientists, startups, and tourists who never could have afforded it previously, but the cheapest way to reach orbit might not be a rocket at all — it could be an elevator.

The space elevator

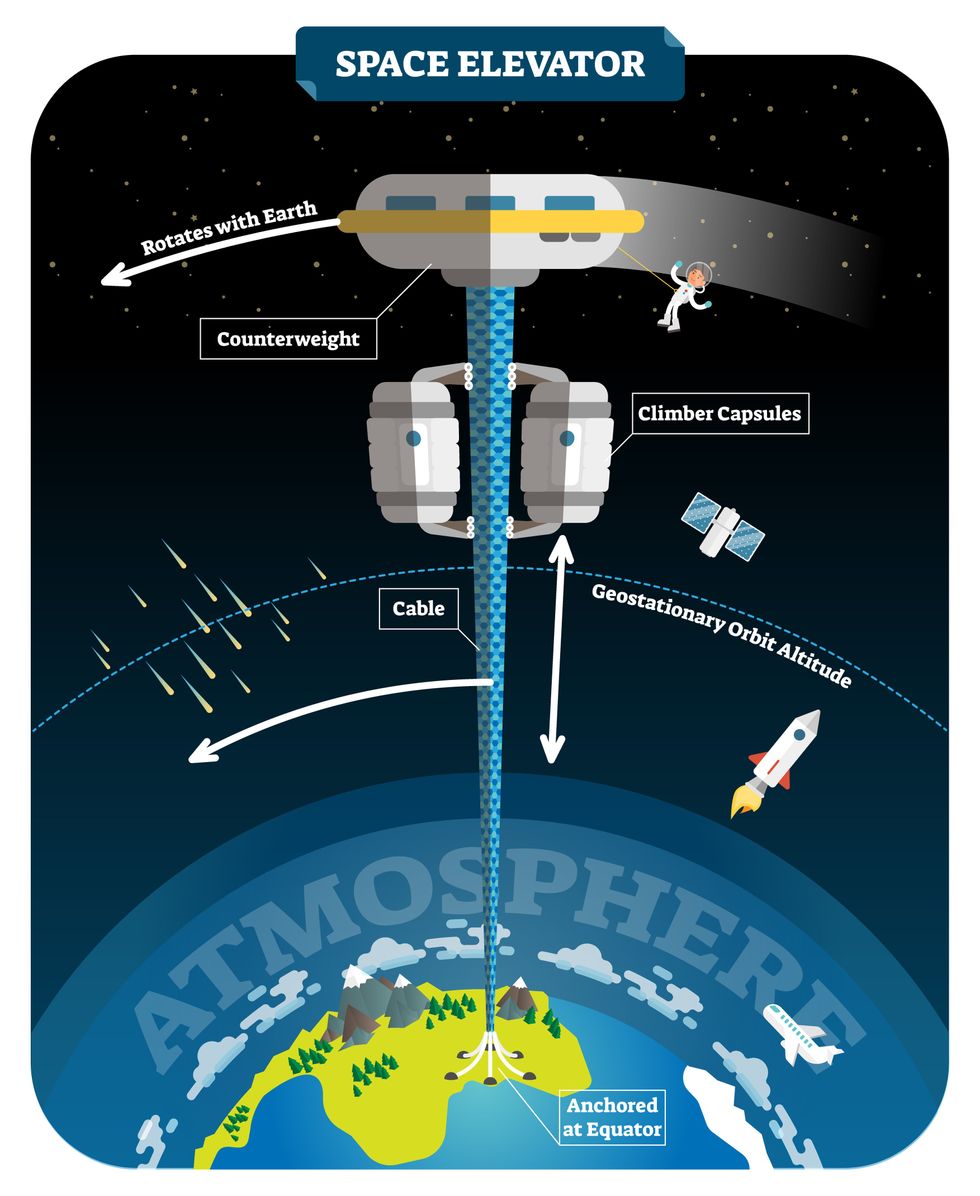

The seeds for a space elevator were first planted by Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1895, who, after visiting the 1,000-foot (305 m) Eiffel Tower, published a paper theorizing about the construction of a structure 22,000 miles (35,400 km) high.

This would provide access to geostationary orbit, an altitude where objects appear to remain fixed above Earth’s surface, but Tsiolkovsky conceded that no material could support the weight of such a tower.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

In 1959, soon after Sputnik, Russian engineer Yuri N. Artsutanov proposed a way around this issue: instead of building a space elevator from the ground up, start at the top. More specifically, he suggested placing a satellite in geostationary orbit and dropping a tether from it down to Earth’s equator. As the tether descended, the satellite would ascend. Once attached to Earth’s surface, the tether would be kept taut, thanks to a combination of gravitational and centrifugal forces.

We could then send electrically powered “climber” vehicles up and down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit. According to physicist Bradley Edwards, who researched the concept for NASA about 20 years ago, it’d cost $10 billion and take 15 years to build a space elevator, but once operational, the cost of sending a payload to any Earth orbit could be as low as $100 per pound.

“Once you reduce the cost to almost a Fed-Ex kind of level, it opens the doors to lots of people, lots of countries, and lots of companies to get involved in space,” Edwards told Space.com in 2005.

In addition to the economic advantages, a space elevator would also be cleaner than using rockets — there’d be no burning of fuel, no harmful greenhouse emissions — and the new transport system wouldn’t contribute to the problem of space junk to the same degree that expendable rockets do.

So, why don’t we have one yet?

Tether troubles

Edwards wrote in his report for NASA that all of the technology needed to build a space elevator already existed except the material needed to build the tether, which needs to be light but also strong enough to withstand all the huge forces acting upon it.

The good news, according to the report, was that the perfect material — ultra-strong, ultra-tiny “nanotubes” of carbon — would be available in just two years.

“[S]teel is not strong enough, neither is Kevlar, carbon fiber, spider silk, or any other material other than carbon nanotubes,” wrote Edwards. “Fortunately for us, carbon nanotube research is extremely hot right now, and it is progressing quickly to commercial production.”Unfortunately, he misjudged how hard it would be to synthesize carbon nanotubes — to date, no one has been able to grow one longer than 21 inches (53 cm).

Further research into the material revealed that it tends to fray under extreme stress, too, meaning even if we could manufacture carbon nanotubes at the lengths needed, they’d be at risk of snapping, not only destroying the space elevator, but threatening lives on Earth.

Looking ahead

Carbon nanotubes might have been the early frontrunner as the tether material for space elevators, but there are other options, including graphene, an essentially two-dimensional form of carbon that is already easier to scale up than nanotubes (though still not easy).

Contrary to Edwards’ report, Johns Hopkins University researchers Sean Sun and Dan Popescu say Kevlar fibers could work — we would just need to constantly repair the tether, the same way the human body constantly repairs its tendons.

“Using sensors and artificially intelligent software, it would be possible to model the whole tether mathematically so as to predict when, where, and how the fibers would break,” the researchers wrote in Aeon in 2018.

“When they did, speedy robotic climbers patrolling up and down the tether would replace them, adjusting the rate of maintenance and repair as needed — mimicking the sensitivity of biological processes,” they continued.Astronomers from the University of Cambridge and Columbia University also think Kevlar could work for a space elevator — if we built it from the moon, rather than Earth.

They call their concept the Spaceline, and the idea is that a tether attached to the moon’s surface could extend toward Earth’s geostationary orbit, held taut by the pull of our planet’s gravity. We could then use rockets to deliver payloads — and potentially people — to solar-powered climber robots positioned at the end of this 200,000+ mile long tether. The bots could then travel up the line to the moon’s surface.

This wouldn’t eliminate the need for rockets to get into Earth’s orbit, but it would be a cheaper way to get to the moon. The forces acting on a lunar space elevator wouldn’t be as strong as one extending from Earth’s surface, either, according to the researchers, opening up more options for tether materials.

“[T]he necessary strength of the material is much lower than an Earth-based elevator — and thus it could be built from fibers that are already mass-produced … and relatively affordable,” they wrote in a paper shared on the preprint server arXiv.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one.

Electrically powered climber capsules could go up down the tether to deliver payloads to any Earth orbit.

Adobe Stock

Some Chinese researchers, meanwhile, aren’t giving up on the idea of using carbon nanotubes for a space elevator — in 2018, a team from Tsinghua University revealed that they’d developed nanotubes that they say are strong enough for a tether.

The researchers are still working on the issue of scaling up production, but in 2021, state-owned news outlet Xinhua released a video depicting an in-development concept, called “Sky Ladder,” that would consist of space elevators above Earth and the moon.

After riding up the Earth-based space elevator, a capsule would fly to a space station attached to the tether of the moon-based one. If the project could be pulled off — a huge if — China predicts Sky Ladder could cut the cost of sending people and goods to the moon by 96 percent.

The bottom line

In the 120 years since Tsiolkovsky looked at the Eiffel Tower and thought way bigger, tremendous progress has been made developing materials with the properties needed for a space elevator. At this point, it seems likely we could one day have a material that can be manufactured at the scale needed for a tether — but by the time that happens, the need for a space elevator may have evaporated.

Several aerospace companies are making progress with their own reusable rockets, and as those join the market with SpaceX, competition could cause launch prices to fall further.

California startup SpinLaunch, meanwhile, is developing a massive centrifuge to fling payloads into space, where much smaller rockets can propel them into orbit. If the company succeeds (another one of those big ifs), it says the system would slash the amount of fuel needed to reach orbit by 70 percent.

Even if SpinLaunch doesn’t get off the ground, several groups are developing environmentally friendly rocket fuels that produce far fewer (or no) harmful emissions. More work is needed to efficiently scale up their production, but overcoming that hurdle will likely be far easier than building a 22,000-mile (35,400-km) elevator to space.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.