Should We Use Technologies to Enhance Morality?

Should we welcome biomedical technologies that could enhance our ability to tell right from wrong and improve behaviors that are considered immoral such as dishonesty, prejudice and antisocial aggression?

Our moral ‘hardware’ evolved over 100,000 years ago while humans were still scratching the savannah. The perils we encountered back then were radically different from those that confront us now. To survive and flourish in the face of complex future challenges our archaic operating systems might need an upgrade – in non-traditional ways.

Morality refers to standards of right and wrong when it comes to our beliefs, behaviors, and intentions. Broadly, moral enhancement is the use of biomedical technology to improve moral functioning. This could include augmenting empathy, altruism, or moral reasoning, or curbing antisocial traits like outgroup bias and aggression.

The claims related to moral enhancement are grand and polarizing: it’s been both tendered as a solution to humanity’s existential crises and bluntly dismissed as an armchair hypothesis. So, does the concept have any purchase? The answer leans heavily on our definition and expectations.

One issue is that the debate is often carved up in dichotomies – is moral enhancement feasible or unfeasible? Permissible or impermissible? Fact or fiction? On it goes. While these gesture at imperatives, trading in absolutes blurs the realities at hand. A sensible approach must resist extremes and recognize that moral disrupters are already here.

We know that existing interventions, whether they occur unknowingly or on purpose, have the power to modify moral dispositions in ways both good and bad. For instance, neurotoxins can promote antisocial behavior. The ‘lead-crime hypothesis’ links childhood lead-exposure to impulsivity, antisocial aggression, and various other problems. Mercury has been associated with cognitive deficits, which might impair moral reasoning and judgement. It’s well documented that alcohol makes people more prone to violence.

So, what about positive drivers? Here’s where it gets more tangled.

Medicine has long treated psychiatric disorders with drugs like sedatives and antipsychotics. However, there’s short mention of morality in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) despite the moral merits of pharmacotherapy – these effects are implicit and indirect. Such cases are regarded as treatments rather than enhancements.

It would be dangerously myopic to assume that moral augmentation is somehow beyond reach.

Conventionally, an enhancement must go beyond what is ‘normal,’ species-typical, or medically necessary – this is known as the ‘treatment-enhancement distinction.’ But boundaries of health and disease are fluid, so whether we call a procedure ‘moral enhancement’ or ‘medical treatment’ is liable to change with shifts in social values, expert opinions, and clinical practices.

Human enhancements are already used for a range of purported benefits: caffeine, smart drugs, and other supplements to boost cognitive performance; cosmetic procedures for aesthetic reasons; and steroids and stimulants for physical advantage. More boldly, cyborgs like Moon Ribas and Neil Harbisson are pushing transpecies boundaries with new kinds of sensory perception. It would be dangerously myopic to assume that moral augmentation is somehow beyond reach.

How might it work?

One possibility for shaping moral temperaments is with neurostimulation devices. These use electrodes to deliver a low-intensity current that alters the electromagnetic activity of specific neural regions. For instance, transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) can target parts of the brain involved in self-awareness, moral judgement, and emotional decision-making. It’s been shown to increase empathy and valued-based learning, and decrease aggression and risk-taking behavior. Many countries already use tDCS to treat pain and depression, but evidence for enhancement effects on healthy subjects is mixed.

Another suggestion is targeting neuromodulators like serotonin and dopamine. Serotonin is linked to prosocial attributes like trust, fairness, and cooperation, but low activity is thought to motivate desires for revenge and harming others. It’s not as simple as indiscriminately boosting brain chemicals though. While serotonin is amenable to SSRIs, precise levels are difficult to measure and track, and there’s no scientific consensus on the “optimum” amount or on whether such a value even exists. Fluctuations due to lifestyle factors such as diet, stress, and exercise add further complexity. Currently, more research is needed on the significance of neuromodulators and their network dynamics across the moral landscape.

There are a range of other prospects. The ‘love drugs’ oxytocin and MDMA mediate pair bonding, cooperation, and social attachment, although some studies suggest that people with high levels of oxytocin are more aggressive toward outsiders. Lithium is a mood stabilizer that has been shown to reduce aggression in prison populations; beta-blockers like propranolol and the supplement omega-3 have similar effects. Increasingly, brain-computer interfaces augur a world of brave possibilities. Such appeals are not without limitations, but they indicate some ways that external tools can positively nudge our moral sentiments.

Who needs morally enhancing?

A common worry is that enhancement technologies could be weaponized for social control by authoritarian regimes, or used like the oppressive eugenics of the early 20th century. Fortunately, the realities are far more mundane and such dystopian visions are fantastical. So, what are some actual possibilities?

Some researchers suggest that neurotechnologies could help to reactivate brain regions of those suffering from moral pathologies, including healthy people with psychopathic traits (like a lack of empathy). Another proposal is using such technology on young people with conduct problems to prevent serious disorders in adulthood.

Most of us aren’t always as ethical as we would like – given the option of ‘priming’ yourself to act in consistent accord with your higher values, would you take it?

A question is whether these kinds of interventions should be compulsory for dangerous criminals. On the other hand, a voluntary treatment for inmates wouldn’t be so different from existing incentive schemes. For instance, some U.S. jurisdictions already offer drug treatment programs in exchange for early release or instead of prison time. Then there’s the difficult question of how we should treat non-criminal but potentially harmful ‘successful’ psychopaths.

Others argue that if virtues have a genetic component, there is no technological reason why present practices of embryo screening for genetic diseases couldn’t also be used for selecting socially beneficial traits.

Perhaps the most immediate scenario is a kind of voluntary moral therapy, which would use biomedicine to facilitate ideal brain-states to augment traditional psychotherapy. Most of us aren’t always as ethical as we would like – given the option of ‘priming’ yourself to act in consistent accord with your higher values, would you take it? Approaches like neurofeedback and psychedelic-assisted therapy could prove helpful.

What are the challenges?

A general challenge is that of setting. Morality is context dependent; what’s good in one environment may be bad in another and vice versa, so we don’t want to throw out the baby with the bathwater. Of course, common sense tells us that some tendencies are more socially desirable than others: fairness, altruism, and openness are clearly preferred over aggression, dishonesty, and prejudice.

One argument is that remoulding ‘brute impulses’ via biology would not count as moral enhancement. This view claims that for an action to truly count as moral it must involve cognition – reasoning, deliberation, judgement – as a necessary part of moral behavior. Critics argue that we should be concerned more with ends rather than means, so ultimately it’s outcomes that matter most.

Another worry is that modifying one biological aspect will have adverse knock-on effects for other valuable traits. Certainly, we must be careful about the network impacts of any intervention. But all stimuli have distributed effects on the body, so it’s really a matter of weighing up the cost/benefit trade-offs as in any standard medical decision.

Is it ethical?

Our values form a big part of who we are – some bioethicists argue that altering morality would pose a threat to character and personal identity. Another claim is that moral enhancement would compromise autonomy by limiting a person’s range of choices and curbing their ‘freedom to fall.’ Any intervention must consider the potential impacts on selfhood and personal liberty, in addition to the wider social implications.

This includes the importance of social and genetic diversity, which is closely tied to considerations of fairness, equality, and opportunity. The history of psychiatry is rife with examples of systematic oppression, like ‘drapetomania’ – the spurious mental illness that was thought to cause African slaves’ desire to flee captivity. Advocates for using moral enhancement technologies to help kids with conduct problems should be mindful that they disproportionately come from low-income communities. We must ensure that any habilitative practice doesn’t perpetuate harmful prejudices by unfairly targeting marginalized people.

Human capacities are the result of environmental influences, and external conditions still coax our biology in unknown ways. Status quo bias for ‘letting nature take its course’ may actually be worse long term – failing to utilize technology for human development may do more harm than good.

Then, there are concerns that morally-enhanced persons would be vulnerable to predation by those who deliberately avoid moral therapies. This relates to what’s been dubbed the ‘bootstrapping problem’: would-be moral enhancement candidates are the types of individuals that benefit from not being morally enhanced. Imagine if every senator was asked to undergo an honesty-boosting procedure prior to entering public office – would they go willingly? Then again, perhaps a technological truth-serum wouldn’t be such a bad requisite for those in positions of stern social consequence.

Advocates argue that biomedical moral betterment would simply offer another means of pursuing the same goals as fixed social mechanisms like religion, education, and community, and non-invasive therapies like cognitive-behavior therapy and meditation. It’s even possible that technological efforts would be more effective. After all, human capacities are the result of environmental influences, and external conditions still coax our biology in unknown ways. Status quo bias for ‘letting nature take its course’ may actually be worse long term – failing to utilize technology for human development may do more harm than good. If we can safely improve ourselves in direct and deliberate ways then there’s no morally significant difference whether this happens via conventional methods or new technology.

Future prospects

Where speculation about human enhancement has led to hype and technophilia, many bioethicists urge restraint. We can be grounded in current science while anticipating feasible medium-term prospects. It’s unlikely moral enhancement heralds any metamorphic post-human utopia (or dystopia), but that doesn’t mean dismissing its transformative potential. In one sense, we should be wary of transhumanist fervour about the salvatory promise of new technology. By the same token we must resist technofear and alarmist efforts to balk social and scientific progress. Emerging methods will continue to shape morality in subtle and not-so-subtle ways – the critical steps are spotting and scaffolding these with robust ethical discussion, public engagement, and reasonable policy options. Steering a bright and judicious course requires that we pilot the possibilities of morally-disruptive technologies.

The future of non-hormonal birth control: Antibodies can stop sperm in their tracks

Many women want non-hormonal birth control. A 22-year-old's findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

Unwanted pregnancy can now be added to the list of preventions that antibodies may be fighting in the near future. For decades, really since the 1980s, engineered monoclonal antibodies have been knocking out invading germs — preventing everything from cancer to COVID. Sperm, which have some of the same properties as germs, may be next.

Not only is there an unmet need on the market for alternatives to hormonal contraceptives, the genesis for the original research was personal for the then 22-year-old scientist who led it. Her findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

The genesis

It’s Suruchi Shrestha’s research — published in Science Translational Medicine in August 2021 and conducted as part of her dissertation while she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — that could change the future of contraception for many women worldwide. According to a Guttmacher Institute report, in the U.S. alone, there were 46 million sexually active women of reproductive age (15–49) who did not want to get pregnant in 2018. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade this year, Shrestha’s research could, indeed, be life changing for millions of American women and their families.

Now a scientist with NextVivo, Shrestha is not directly involved in the development of the contraceptive that is based on her research. But, back in 2016 when she was going through her own problems with hormonal contraceptives, she “was very personally invested” in her research project, Shrestha says. She was coping with a long list of negative effects from an implanted hormonal IUD. According to the Mayo Clinic, those can include severe pelvic pain, headaches, acute acne, breast tenderness, irregular bleeding and mood swings. After a year, she had the IUD removed, but it took another full year before all the side effects finally subsided; she also watched her sister suffer the “same tribulations” after trying a hormonal IUD, she says.

For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, Shrestha says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

Shrestha unshelved antibody research that had been sitting idle for decades. It was in the late 80s that scientists in Japan first tried to develop anti-sperm antibodies for contraceptive use. But, 35 years ago, “Antibody production had not been streamlined as it is now, so antibodies were very expensive,” Shrestha explains. So, they shifted away from birth control, opting to focus on developing antibodies for vaccines.

Over the course of the last three decades, different teams of researchers have been working to make the antibody more effective, bringing the cost down, though it’s still expensive, according to Shrestha. For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, she says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

The problem

The problem with contraceptives for women, Shrestha says, is that all but a few of them are hormone-based or have other negative side effects. In fact, some studies and reports show that millions of women risk unintended pregnancy because of medical contraindications with hormone-based contraceptives or to avoid the risks and side effects. While there are about a dozen contraceptive choices for women, there are two for men: the condom, considered 98% effective if used correctly, and vasectomy, 99% effective. Neither of these choices are hormone-based.

On the non-hormonal side for women, there is the diaphragm which is considered only 87 percent effective. It works better with the addition of spermicides — Nonoxynol-9, or N-9 — however, they are detergents; they not only kill the sperm, they also erode the vaginal epithelium. And, there’s the non-hormonal IUD which is 99% effective. However, the IUD needs to be inserted by a medical professional, and it has a number of negative side effects, including painful cramping at a higher frequency and extremely heavy or “abnormal” and unpredictable menstrual flows.

The hormonal version of the IUD, also considered 99% effective, is the one Shrestha used which caused her two years of pain. Of course, there’s the pill, which needs to be taken daily, and the birth control ring which is worn 24/7. Both cause side effects similar to the other hormonal contraceptives on the market. The ring is considered 93% effective mostly because of user error; the pill is considered 99% effective if taken correctly.

“That’s where we saw this opening or gap for women. We want a safe, non-hormonal contraceptive,” Shrestha says. Compounding the lack of good choices, is poor access to quality sex education and family planning information, according to the non-profit Urban Institute. A focus group survey suggested that the sex education women received “often lacked substance, leaving them feeling unprepared to make smart decisions about their sexual health and safety,” wrote the authors of the Urban Institute report. In fact, nearly half (45%, or 2.8 million) of the pregnancies that occur each year in the US are unintended, reports the Guttmacher Institute. Globally the numbers are similar. According to a new report by the United Nations, each year there are 121 million unintended pregnancies, worldwide.

The science

The early work on antibodies as a contraceptive had been inspired by women with infertility. It turns out that 9 to 12 percent of women who are treated for infertility have antibodies that develop naturally and work against sperm. Shrestha was encouraged that the antibodies were specific to the target — sperm — and therefore “very safe to use in women.” She aimed to make the antibodies more stable, more effective and less expensive so they could be more easily manufactured.

Since antibodies tend to stick to things that you tell them to stick to, the idea was, basically, to engineer antibodies to stick to sperm so they would stop swimming. Shrestha and her colleagues took the binding arm of an antibody that they’d isolated from an infertile woman. Then, targeting a unique surface antigen present on human sperm, they engineered a panel of antibodies with as many as six to 10 binding arms — “almost like tongs with prongs on the tongs, that bind the sperm,” explains Shrestha. “We decided to add those grabbers on top of it, behind it. So it went from having two prongs to almost 10. And the whole goal was to have so many arms binding the sperm that it clumps it” into a “dollop,” explains Shrestha, who earned a patent on her research.

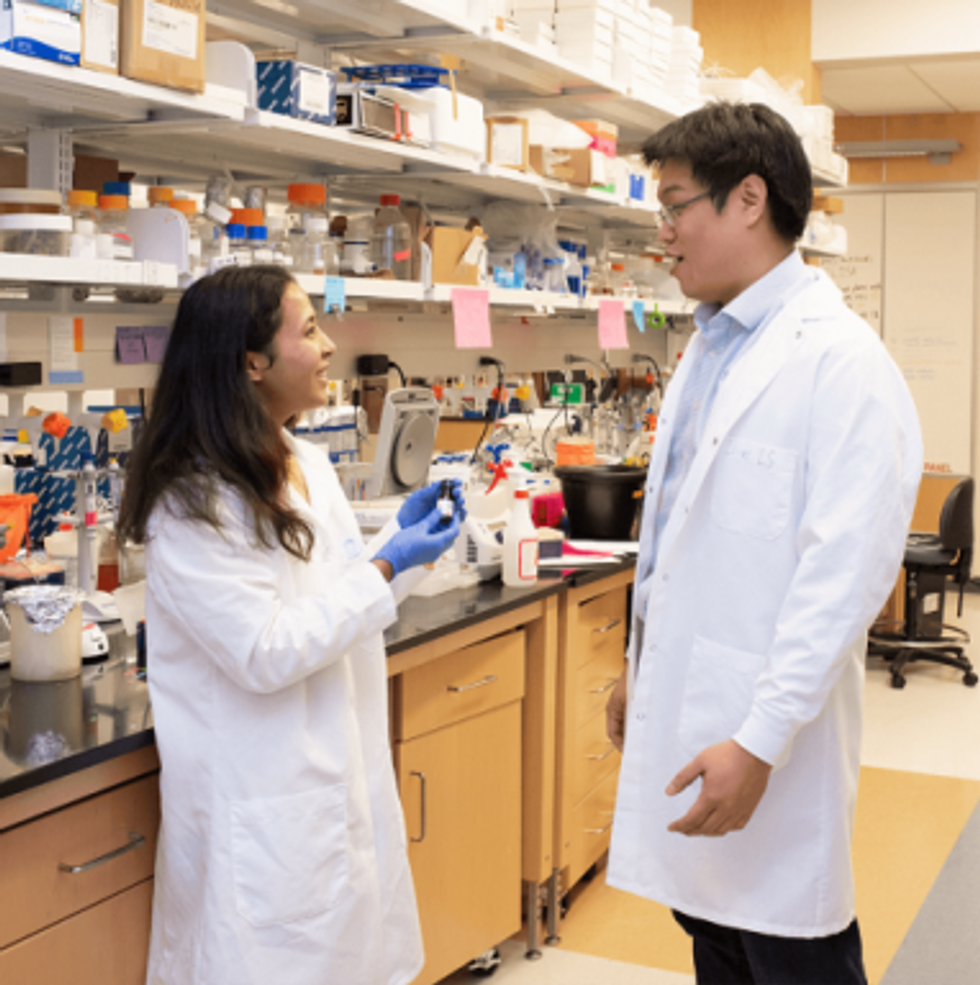

Suruchi Shrestha works in the lab with a colleague. In 2016, her research on antibodies for birth control was inspired by her own experience with side effects from an implanted hormonal IUD.

UNC - Chapel Hill

The sperm stays right where it met the antibody, never reaching the egg for fertilization. Eventually, and naturally, “Our vaginal system will just flush it out,” Shrestha explains.

“She showed in her early studies that [she] definitely got the sperm immotile, so they didn't move. And that was a really promising start,” says Jasmine Edelstein, a scientist with an expertise in antibody engineering who was not involved in this research. Shrestha’s team at UNC reproduced the effect in the sheep, notes Edelstein, who works at the startup Be Biopharma. In fact, Shrestha’s anti-sperm antibodies that caused the sperm to agglutinate, or clump together, were 99.9% effective when delivered topically to the sheep’s reproductive tracts.

The future

Going forward, Shrestha thinks the ideal approach would be delivering the antibodies through a vaginal ring. “We want to use it at the source of the spark,” Shrestha says, as opposed to less direct methods, such as taking a pill. The ring would dissolve after one month, she explains, “and then you get another one.”

Engineered to have a long shelf life, the anti-sperm antibody ring could be purchased without a prescription, and women could insert it themselves, without a doctor. “That's our hope, so that it is accessible,” Shrestha says. “Anybody can just go and grab it and not worry about pregnancy or unintended pregnancy.”

Her patented research has been licensed by several biotech companies for clinical trials. A number of Shrestha’s co-authors, including her lab advisor, Sam Lai, have launched a company, Mucommune, to continue developing the contraceptives based on these antibodies.

And, results from a small clinical trial run by researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine show that a dissolvable vaginal film with antibodies was safe when tested on healthy women of reproductive age. That same group of researchers earlier this year received a $7.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health for further research on monoclonal antibody-based contraceptives, which have also been shown to block transmission of viruses, like HIV.

“As the costs come down, this becomes a more realistic option potentially for women,” says Edelstein. “The impact could be tremendous.”

The Friday Five: An mRNA vaccine works against cancer, new research suggests

In this week's Friday Five, an mRNA vaccine works against cancer for the first time. Plus, these cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power, a new theory for what causes aging, bacteria that could get you excited to work out, and a reason for sex differences in Alzheimer's.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- An mRNA vaccine that works against cancer

- These cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power

- A new theory for what causes aging

- Can bacteria make you excited to work out?

- Why women get Alzheimer's more often than men