The New Prospective Parenthood: When Does More Info Become Too Much?

Obstetric ultrasound of a fourth-month fetus.

Peggy Clark was 12 weeks pregnant when she went in for a nuchal translucency (NT) scan to see whether her unborn son had Down syndrome. The sonographic scan measures how much fluid has accumulated at the back of the baby's neck: the more fluid, the higher the likelihood of an abnormality. The technician said the baby was in such an odd position, the test couldn't be done. Clark, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, was told to come back in a week and a half to see if the baby had moved.

"With the growing sophistication of prenatal tests, it seems that the more questions are answered, the more new ones arise."

"It was like the baby was saying, 'I don't want you to know,'" she recently recalled.

When they went back, they found the baby had a thickened neck. It's just one factor in identifying Down's, but it's a strong indication. At that point, she was 13 weeks and four days pregnant. She went to the doctor the next day for a blood test. It took another two weeks for the results, which again came back positive, though there was still a .3% margin of error. Clark said she knew she wanted to terminate the pregnancy if the baby had Down's, but she didn't want the guilt of knowing there was a small chance the tests were wrong. At that point, she was too late to do a Chorionic villus sampling (CVS), when chorionic villi cells are removed from the placenta and sequenced. And she was too early to do an amniocentesis, which isn't done until between 14 and 20 weeks of the pregnancy. So she says she had to sit and wait, calling those few weeks "brutal."

By the time they did the amnio, she was already nearly 18 weeks pregnant and was getting really big. When that test also came back positive, she made the anguished decision to end the pregnancy.

Now, three years after Clark's painful experience, a newer form of prenatal testing routinely gives would-be parents more information much earlier on, especially for women who are over 35. As soon as nine weeks into their pregnancies, women can have a simple blood test to determine if there are abnormalities in the DNA of chromosomes 21, which indicates Down syndrome, as well as in chromosomes 13 and 18. Using next-generation sequencing technologies, the test separates out and examines circulating fetal cells in the mother's blood, which eliminates the risks of drawing fluid directly from the fetus or placenta.

"Finding out your baby has Down syndrome at 11 or 12 weeks is much easier for parents to make any decision they may want to make, as opposed to 16 or 17 weeks," said Dr. Leena Nathan, an obstetrician-gynecologist in UCLA's healthcare system. "People are much more willing or able to perhaps make a decision to terminate the pregnancy."

But with the growing sophistication of prenatal tests, it seems that the more questions are answered, the more new ones arise--questions that previous generations have never had to face. And as genomic sequencing improves in its predictive accuracy at the earliest stages of life, the challenges only stand to increase. Imagine, for example, learning your child's lifetime risk of breast cancer when you are ten weeks pregnant. Would you terminate if you knew she had a 70 percent risk? What about 40 percent? Lots of hard questions. Few easy answers. Once the cost of whole genome sequencing drops low enough, probably within the next five to ten years according to experts, such comprehensive testing may become the new standard of care. Welcome to the future of prospective parenthood.

"In one way, it's a blessing to have this information. On the other hand, it's very difficult to deal with."

How Did We Get Here?

Prenatal testing is not new. In 1979, amniocentesis was used to detect whether certain inherited diseases had been passed on to the fetus. Through the 1980s, parents could be tested to see if they carried disease like Tay-Sachs, Sickle cell anemia, Cystic fibrosis and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. By the early 1990s, doctors could test for even more genetic diseases and the CVS test was beginning to become available.

A few years later, a technique called preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) emerged, in which embryos created in a lab with sperm and harvested eggs would be allowed to grow for several days and then cells would be removed and tested to see if any carried genetic diseases. Those that weren't affected could be transferred back to the mother. Once in vitro fertilization (IVF) took off, so did genetic testing. The labs test the embryonic cells and get them back to the IVF facilities within 24 hours so that embryo selection can occur. In the case of IVF, genetic tests are done so early, parents don't even have to decide whether to terminate a pregnancy. Embryos with issues often aren't even used.

"It was a very expensive endeavor but exciting to see our ability to avoid disorders, especially for families that don't want to terminate a pregnancy," said Sara Katsanis, an expert in genetic testing who teaches at Duke University. "In one way, it's a blessing to have this information (about genetic disorders). On the other hand, it's very difficult to deal with. To make that decision about whether to terminate a pregnancy is very hard."

Just Because We Can, Does It Mean We Should?

Parents in the future may not only find out whether their child has a genetic disease but will be able to potentially fix the problem through a highly controversial process called gene editing. But because we can, does it mean we should? So far, genes have been edited in other species, but to date, the procedure has not been used on an unborn child for reproductive purposes apart from research.

"There's a lot of bioethics debate and convening of groups to try to figure out where genetic manipulation is going to be useful and necessary, and where it is going to need some restrictions," said Katsanis. She notes that it's very useful in areas like cancer research, so one wouldn't want to over-regulate it.

There are already some criteria as to which genes can be manipulated and which should be left alone, said Evan Snyder, professor and director of the Center for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine at Sanford Children's Health Research Center in La Jolla, Calif. He noted that genes don't stand in isolation. That is, if you modify one that causes disease, will it disrupt others? There may be unintended consequences, he added.

"As the technical dilemmas get fixed, some of the ethical dilemmas get fixed. But others arise. It's kind of like ethical whack-a-mole."

But gene editing of embryos may take years to become an acceptable practice, if ever, so a more pressing issue concerns the rationale behind embryo selection during IVF. Prospective parents can end up with anywhere from zero to thirty embryos from the procedure and must choose only one (rarely two) to implant. Since embryos are routinely tested now for certain diseases, and selected or discarded based on that information, should it be ethical—and legal—to make selections based on particular traits, too? To date so far, parents can select for gender, but no other traits. Whether trait selection becomes routine is a matter of time and business opportunity, Katsanis said. So far, the old-fashioned way of making a baby combined with the luck of the draw seems to be the preferred method for the marketplace. But that could change.

"You can easily see a family deciding not to implant a lethal gene for Tay-Sachs or Duchene or Cystic fibrosis. It becomes more ethically challenging when you make a decision to implant girls and not any of the boys," said Snyder. "And then as we get better and better, we can start assigning genes to certain skills and this starts to become science fiction."

Once a pregnancy occurs, prospective parents of all stripes will face decisions about whether to keep the fetus based on the information that increasingly robust prenatal testing will provide. What influences their decision is the crux of another ethical knot, said Snyder. A clear-cut rationale would be if the baby is anencephalic, or it has no brain. A harder one might be, "It's a girl, and I wanted a boy," or "The child will only be 5' 2" tall in adulthood."

"Those are the extremes, but the ultimate question is: At what point is it a legitimate response to say, I don't want to keep this baby?'" he said. Of course, people's responses will vary, so the bigger conundrum for society is: Where should a line be drawn—if at all? Should a woman who is within the legal scope of termination (up to around 24 weeks, though it varies by state) be allowed to terminate her pregnancy for any reason whatsoever? Or must she have a so-called "legitimate" rationale?

"As the technical dilemmas get fixed, some of the ethical dilemmas get fixed. But others arise. It's kind of like ethical whack-a-mole," Snyder said.

One of the newer moles to emerge is, if one can fix a damaged gene, for how long should it be fixed? In one child? In the family's whole line, going forward? If the editing is done in the embryo right after the egg and sperm have united and before the cells begin dividing and becoming specialized, when, say, there are just two or four cells, it will likely affect that child's entire reproductive system and thus all of that child's progeny going forward.

"This notion of changing things forever is a major debate," Snyder said. "It literally gets into metaphysics. On the one hand, you could say, well, wouldn't it be great to get rid of Cystic fibrosis forever? What bad could come of getting rid of a mutant gene forever? But we're not smart enough to know what other things the gene might be doing, and how disrupting one thing could affect this network."

As with any tool, there are risks and benefits, said Michael Kalichman, Director of the Research Ethics Program at the University of California San Diego. While we can envision diverse benefits from a better understanding of human biology and medicine, it is clear that our species can also misuse those tools – from stigmatizing children with certain genetic traits as being "less than," aka dystopian sci-fi movies like Gattaca, to judging parents for making sure their child carries or doesn't carry a particular trait.

"The best chance to ensure that the benefits of this technology will outweigh the risks," Kalichman said, "is for all stakeholders to engage in thoughtful conversations, strive for understanding of diverse viewpoints, and then develop strategies and policies to protect against those uses that are considered to be problematic."

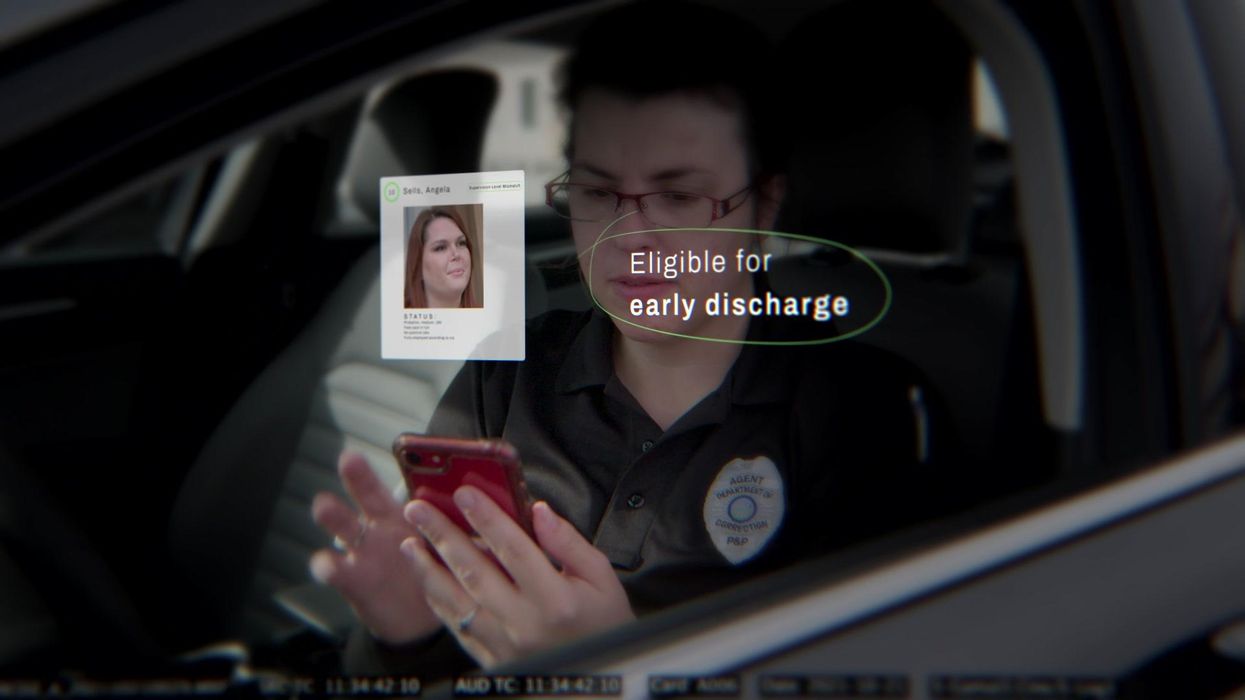

New tech for prison reform spreads to 11 states

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, costing $182 billion per year, partly because its antiquated data systems often fail to identify people who should be released. A tech nonprofit is trying to change that.

A new non-profit called Recidiviz is using data technology to reduce the size of the U.S. criminal justice system. The bi-coastal company (SF and NYC) is currently working with 11 states to improve their systems and, so far, has helped remove nearly 69,000 people — ones left floundering in jail or on parole when they should have been released.

“The root cause is fragmentation,” says Clementine Jacoby, 31, a software engineer who worked at Google before co-founding Recidiviz in 2019. In the 1970s and 80s, the U.S. built a series of disconnected data systems, and this patchwork is still being used by criminal justice authorities today. It requires parole officers to manually calculate release dates, leading to errors in many cases. “[They] have done everything they need to do to earn their release, but they're still stuck in the system,” Jacoby says.

Recidiviz has built a platform that connects the different databases, with the goal of identifying people who are already qualified for release but remain behind bars or on supervision. “Think of Recidiviz like Google Maps,” says Jacoby, who worked on Maps when she was at the tech giant. Google Maps takes in data from different sources – satellite images, street maps, local business data — and organizes it into one easy view. “Recidiviz does something similar with criminal justice data,” Jacoby explains, “making it easy to identify people eligible to come home or to move to less intensive levels of supervision.”

People like Jacoby’s uncle. His experience with incarceration is what inspired her passion for criminal justice reform in the first place.

The problems are vast

The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world — 2 million people according to the watchdog group, Prison Policy Initiative — at a cost of $182 billion a year. The numbers could be a lot lower if not for an array of problems including inaccurate sentencing calculations, flawed algorithms and parole violations laws.

Sentencing miscalculations

To determine eligibility for release, the current system requires corrections officers to check 21 different requirements spread across five different databases for each of the 90 to 100 people under their supervision. These manual calculations are time prohibitive, says Jacoby, and fall victim to human error.

In addition, Recidiviz found that policies aimed at helping to reduce the prison population don’t always work correctly. A key example is time off for good behavior laws that allow inmates to earn one day off for every 30 days of good behavior. Some states' data systems are built to calculate time off as one day per month of good behavior, rather than per day. Over the course of a decade-long sentence, Jacoby says these miscalculations can lead to a huge discrepancy in the calculated release data and the actual release date.

Algorithms

Commercial algorithm-based software systems for risk assessment continue to be widely used in the criminal justice system, even though a 2018 study published in Science Advances exposed their limitations. After the study went viral, it took three years for the Justice Department to issue a report on their own flawed algorithms used to reduce the federal prison population as part of the 2018 First Step Act. The program, it was determined, overestimated the risk of putting inmates of color into early-release programs.

Despite its name, Recidiviz does not build these types of algorithms for predicting recidivism, or whether someone will commit another crime after being released from prison. Rather, Jacoby says the company’s "descriptive analytics” approach is specifically intended to weed out incarceration inequalities and avoid algorithmic pitfalls.

Parole violation laws

Research shows that 350,000 people a year — about a quarter of the total prison population — are sent back not because they’ve committed another crime, but because they’ve broken a specific rule of their probation. “Things that wouldn't send you or I to prison, but would send someone on parole,” such as crossing county lines or being in the presence of alcohol when they shouldn’t be, are inflating the prison population, says Jacoby.

It’s personal for the co-founder and CEO

“I grew up with an uncle who went into the prison system,” Jacoby says. At 19, he was sentenced to ten years in prison for a non-violent crime. A few months after being released from jail, he was sent back for a non-violent parole violation.

“For my family, the fact that one in four prison admissions are driven not by a crime but by someone who's broken a rule on probation and parole was really profound because that happened to my uncle,” Jacoby says. The experience led her to begin studying criminal justice in high school, then college. She continued her dive into how the criminal justice system works as part of her Passion Project while at Google, a program that allows employees to spend 20 percent of their time on pro-bono work. Two colleagues whose family members had also been stuck in the system joined her.

As part of the project, Jacoby interviewed hundreds of people involved in the criminal justice system. “Those on the right, those on the left, agreed that bad data was slowing down reform,” she says. Their research brought them to North Dakota where they began to understand the root of the problem. The corrections department is making “huge, consequential decisions every day [without] … the data,” Jacoby says. In a new video by Recidiviz not yet released, Jacoby recounts her exchange with the state’s director of corrections who told her, “‘It’s not that we have the data and we just don’t know how to make it public; we don’t have the information you think we have.'"

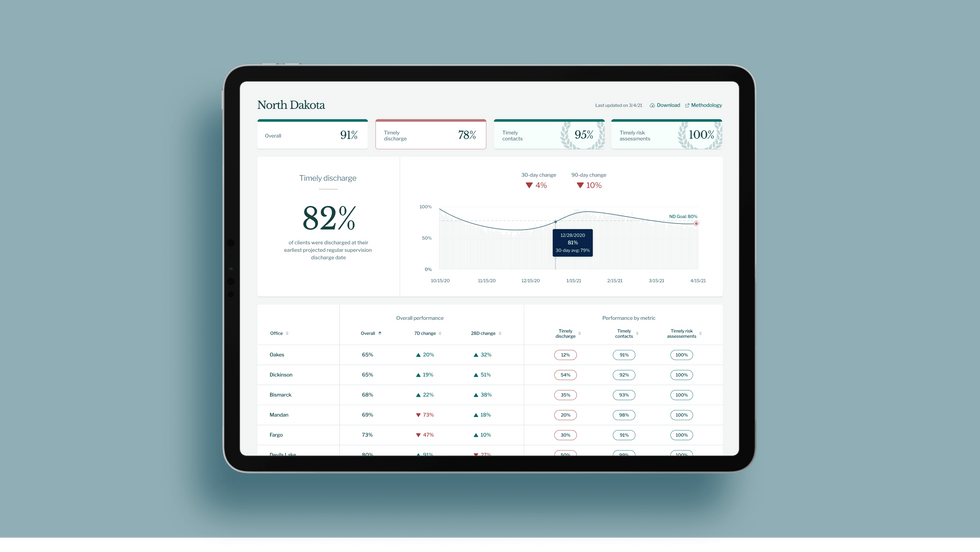

A mock-up (with fake data) of the types of dashboards and insights that Recidiviz provides to state governments.

Recidiviz

As a software engineer, Jacoby says the comment made no sense to her — until she witnessed it first-hand. “We spent a lot of time driving around in cars with corrections directors and parole officers watching them use these incredibly taxing, frankly terrible, old data systems,” Jacoby says.

As they weeded through thousands of files — some computerized, some on paper — they unearthed the consequences of bad data: Hundreds of people in prison well past their release date and thousands more whose release from parole was delayed because of minor paperwork issues. They found individuals stuck in parole because they hadn’t checked one last item off their eligibility list — like simply failing to provide their parole officer with a paystub. And, even when parolees advocated for themselves, the archaic system made it difficult for their parole officers to confirm their eligibility, so they remained in the system. Jacoby and her team also unpacked specific policies that drive racial disparities — such as fines and fees.

The Solution

It’s more than a trivial technical challenge to bring the incomplete, fragmented data onto a 21st century data platform. It takes months for Recidiviz to sift through a state’s information systems to connect databases “with the goal of tracking a person all the way through their journey and find out what’s working for 18- to 25-year-old men, what’s working for new mothers,” explains Jacoby in the video.

TED Talk: How bad data traps people in the U.S. justice system

TED Fellow Clementine Jacoby's TED Talk went live on Jan. 13. It describes how we can fix bad data in the criminal justice system, "bringing thousands of people home, reducing costs and improving public safety along the way."

Clementine Jacoby • TED2022

Ojmarrh Mitchell, an associate professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Arizona State University, who is not involved with the company, says what Recidiviz is doing is “remarkable.” His perspective goes beyond academic analysis. In his pre-academic years, Mitchell was a probation officer, working within the framework of the “well known, but invisible” information sharing issues that plague criminal justice departments. The flexibility of Recidiviz’s approach is what makes it especially innovative, he says. “They identify the specific gaps in each jurisdiction and tailor a solution for that jurisdiction.”

On the downside, the process used by Recidiviz is “a bit opaque,” Mitchell says, with few details available on how Recidiviz designs its tools and tracks outcomes. By sharing more information about how its actions lead to progress in a given jurisdiction, Recidiviz could help reformers in other places figure out which programs have the best potential to work well.

The eleven states in which Recidiviz is working include California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Pennsylvania and Tennessee. And a pilot program launched last year in Idaho, if scaled nationally, with could reduce the number of people in the criminal justice system by a quarter of a million people, Jacoby says. As part of the pilot, rather than relying on manual calculations, Recidiviz is equipping leaders and the probation officers with actionable information with a few clicks of an app that Recidiviz built.

Mitchell is disappointed that there’s even the need for Recidiviz. “This is a problem that government agencies have a responsibility to address,” he says. “But they haven’t.” For one company to come along and fill such a large gap is “remarkable.”

How Leqembi became the biggest news in Alzheimer’s disease in 40 years, and what comes next

Betsy Groves, 73, with her granddaughter. Groves learned in 2021 that she has Alzheimer's disease. She hopes to take Leqembi, a drug approved by the FDA last week.

A few months ago, Betsy Groves traveled less than a mile from her home in Cambridge, Mass. to give a talk to a bunch of scientists. The scientists, who worked for the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai, wanted to know how she lived her life, how she thought about her future, and what it was like when a doctor’s appointment in 2021 gave her the worst possible news. Groves, 73, has Alzheimer’s disease. She caught it early, through a lumbar puncture that showed evidence of amyloid, an Alzheimer’s hallmark, in her cerebrospinal fluid. As a way of dealing with her diagnosis, she joined the Alzheimer’s Association’s National Early-Stage Advisory Board, which helped her shift into seeing her diagnosis as something she could use to help others.

After her talk, Groves stayed for lunch with the scientists, who were eager to put a face to their work. Biogen and Eisai were about to release the first drug to successfully combat Alzheimer’s in 40 years of experimental disaster. Their drug, which is known by the scientific name lecanemab and the marketing name Leqembi, was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last Friday, Jan. 6, after a study in 1,800 people showed that it reduced cognitive decline by 27 percent over 18 months.

It is no exaggeration to say that this result is a huge deal. The field of Alzheimer’s drug development has been absolutely littered with failures. Almost everything researchers have tried has tanked in clinical trials. “Most of the things that we've done have proven not to be effective, and it's not because we haven’t been taking a ton of shots at goal,” says Anton Porsteinsson, director of the University of Rochester Alzheimer's Disease Care, Research, and Education Program, who worked on the lecanemab trial. “I think it's fair to say you don't survive in this field unless you're an eternal optimist.”

As far back as 1984, a cure looked like it was within reach: Scientists discovered that the sticky plaques that develop in the brains of those who have Alzheimer’s are made up of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. Buildup of beta-amyloid seemed to be sufficient to disrupt communication between, and eventually kill, memory cells. If that was true, then the cure should be straightforward: Stop the buildup of beta-amyloid; stop the Alzheimer’s disease.

It wasn’t so simple. Over the next 38 years, hundreds of drugs designed either to interfere with the production of abnormal amyloid or to clear it from the brain flamed out in trials. It got so bad that neuroscience drug divisions at major pharmaceutical companies (AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, GSK, Amgen) closed one by one, leaving the field to smaller, scrappier companies, like Cambridge-based Biogen and Tokyo-based Eisai. Some scientists began to dismiss the amyloid hypothesis altogether: If this protein fragment was so important to the disease, why didn’t ridding the brain of it do anything for patients? There was another abnormal protein that showed up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, called tau. Some researchers defected to the tau camp, or came to believe the proteins caused damage in combination.

The situation came to a head in 2021, when the FDA granted provisional approval to a drug called aducanumab, marketed as Aduhelm, against the advice of its own advisory council. The approval was based on proof that Aduhelm reduced beta-amyloid in the brain, even though one research trial showed it had no effect on people’s symptoms or daily life. Aduhelm could also cause serious side effects, like brain swelling and amyloid related imaging abnormalities (known as ARIA, these are basically micro-bleeds that appear on MRI scans). Without a clear benefit to memory loss that would make these risks worth it, Medicare refused to pay for Aduhelm among the general population. Two congressional committees launched an investigation into the drug’s approval, citing corporate greed, lapses in protocol, and an unjustifiably high price. (Aduhelm was also produced by the pharmaceutical company Biogen.)

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world.

So far, Leqembi is like Aduhelm in that it has been given accelerated approval only for its ability to remove amyloid from the brain. Both are monoclonal antibodies that direct the immune system to attack and clear dysfunctional beta-amyloid. The difference is that, while that’s all Aduhelm was ever shown to do, Leqembi’s makers have already asked the FDA to give it full approval – a decision that would increase the likelihood that Medicare will cover it – based on data that show it also improves Alzheimer’s sufferer’s lives. Leqembi targets a different type of amyloid, a soluble version called “protofibrils,” and that appears to change the effect. “It can give individuals and their families three, six months longer to be participating in daily life and living independently,” says Claire Sexton, PhD, senior director of scientific programs & outreach for the Alzheimer's Association. “These types of changes matter for individuals and for their families.”

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. It does not halt or reverse the disease, and people do not get better. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world. It has “a rather small effect,” wrote NIH Alzheimer’s researcher Madhav Thambisetty, MD, PhD, in an email to Leaps.org. “It is unclear how meaningful this difference will be to patients, and it is unlikely that this level of difference will be obvious to a patient (or their caregivers).” Another issue is cost: Leqembi will become available to patients later this month, but Eisai is setting the price at $26,500 per year, meaning that very few patients will be able to afford it unless Medicare chooses to reimburse them for it.

The same side effects that plagued Aduhelm are common in Leqembi treatment as well. In many patients, amyloid doesn’t just accumulate around neurons, it also forms deposits in the walls of blood vessels. Blood vessels that are shot through with amyloid are more brittle. If you infuse a drug that targets amyloid, brittle blood vessels in the brain can develop leakage that results in swelling or bleeds. Most of these come with no symptoms, and are only seen during testing, which is why they are called “imaging abnormalities.” But in situations where patients have multiple diseases or are prescribed incompatible drugs, they can be serious enough to cause death. The three deaths reported from Leqembi treatment (so far) are enough to make Thambisetty wonder “how well the drug may be tolerated in real world clinical practice where patients are likely to be sicker and have multiple other medical conditions in contrast to carefully selected patients in clinical trials.”

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval.

Still, there are reasons to be excited. A successful Alzheimer’s drug can pave the way for combination studies, in which patients try a known effective drug alongside newer, more experimental ones; or preventative studies, which take place years before symptoms occur. It also represents enormous strides in researchers’ understanding of the disease. For example, drug dosages have increased massively—in some cases quadrupling—from the early days of Alzheimer’s research. And patient selection for studies has changed drastically as well. Doctors now know that you’ve got to catch the disease early, through PET-scans or CSF tests for amyloid, if you want any chance of changing its course.

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval. His lab already uses blood tests for different types of amyloid, for different types of tau, and for measures of neuroinflammation, neural damage, and synaptic health, but commercially available versions from companies like C2N, Quest, and Fuji Rebio are likely to hit the market in the next couple of years. “[They are] going to transform the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease,” Porsteinsson says. “If someone is experiencing memory problems, their physicians will be able to order a blood test that will tell us if this is the result of changes in your brain due to Alzheimer's disease. It will ultimately make it much easier to identify people at a very early stage of the disease, where they are most likely to benefit from treatment.”

Learn more about new blood tests to detect Alzheimer's

Early detection can help patients for more philosophical reasons as well. Betsy Groves credits finding her Alzheimer’s early with giving her the space to understand and process the changes that were happening to her before they got so bad that she couldn’t. She has been able to update her legal documents and, through her role on the Advisory Group, help the Alzheimer’s Association with developing its programs and support services for people in the early stages of the disease. She still drives, and because she and her husband love to travel, they are hoping to get out of grey, rainy Cambridge and off to Texas or Arizona this spring.

Because her Alzheimer’s disease involves amyloid deposits (a “substantial portion” do not, says Claire Sexton, which is an additional complication for research), and has not yet reached an advanced stage, Groves may be a good candidate to try Leqembi. She says she’d welcome the opportunity to take it. If she can get access, Groves hopes the drug will give her more days to be fully functioning with her husband, daughters, and three grandchildren. Mostly, she avoids thinking about what the latter stages of Alzheimer’s might be like, but she knows the time will come when it will be her reality. “So whatever lecanemab can do to extend my more productive ways of engaging with relationships in the world,” she says. “I'll take that in a minute.”