Some companies claim remote work hurts wellbeing. Research shows the opposite.

Leaders at Google and other companies are trying to get workers to return to the office, saying remote and hybrid work disrupt work-life boundaries and well-being. These arguments conflict with research on remote work and wellness.

Many leaders at top companies are trying to get workers to return to the office. They say remote and hybrid work are bad for their employees’ mental well-being and lead to a sense of social isolation, meaninglessness, and lack of work-life boundaries, so we should just all go back to office-centric work.

One example is Google, where the company’s leadership is defending its requirement of mostly in-office work for all staff as necessary to protect social capital, meaning people’s connections to and trust in one another. That’s despite a survey of over 1,000 Google employees showing that two-thirds feel unhappy about being forced to work in the office three days per week. In internal meetings and public letters, many have threatened to leave, and some are already quitting to go to other companies with more flexible options.

Last month, GM rolled out a policy similar to Google’s, but had to backtrack because of intense employee opposition. The same is happening in some places outside of the U.S. For instance, three-fifths of all Chinese employers are refusing to offer permanent remote work options, according to a survey this year from The Paper.

For their claims that remote work hurts well-being, some of these office-centric traditionalists cite a number of prominent articles. For example, Arthur Brooks claimed in an essay that “aggravation from commuting is no match for the misery of loneliness, which can lead to depression, substance abuse, sedentary behavior, and relationship damage, among other ills.” An article in Forbes reported that over two-thirds of employees who work from home at least part of the time had trouble getting away from work at the end of the day. And Fast Company has a piece about how remote work can “exacerbate existing mental health issues” like depression and anxiety.

For his part, author Malcolm Gladwell has also championed a swift return to the office, saying there is a “core psychological truth, which is we want you to have a feeling of belonging and to feel necessary…I know it’s a hassle to come into the office, but if you’re just sitting in your pajamas in your bedroom, is that the work life you want to live?”

These arguments may sound logical to some, but they fly in the face of research and my own experience as a behavioral scientist and as a consultant to Fortune 500 companies. In these roles, I have seen the pitfalls of in-person work, which can be just as problematic, if not more so. Remote work is not without its own challenges, but I have helped 21 companies implement a series of simple steps to address them.

Research finds that remote work is actually better for you

The trouble with the articles described above - and claims by traditionalist business leaders and gurus - stems from a sneaky misdirection. They decry the negative impact of remote and hybrid work for wellbeing. Yet they gloss over the damage to wellbeing caused by the alternative, namely office-centric work.

It’s like comparing remote and hybrid work to a state of leisure. Sure, people would feel less isolated if they could hang out and have a beer with their friends instead of working. They could take care of their existing mental health issues if they could visit a therapist. But that’s not in the cards. What’s in the cards is office-centric work. That means the frustration of a long commute to the office, sitting at your desk in an often-uncomfortable and oppressive open office for at least 8 hours, having a sad desk lunch and unhealthy snacks, sometimes at an insanely expensive cost and, for making it through this series of insults, you’re rewarded with more frustration while commuting back home.

In a 2022 survey, the vast majority of respondents felt that working remotely improved their work-life balance. Much of that improvement stemmed from saving time due to not needing to commute and having a more flexible schedule.

So what happens when we compare apples to apples? That’s when we need to hear from the horse’s mouth: namely, surveys of employees themselves, who experienced both in-office work before the pandemic, and hybrid and remote work after COVID struck.

Consider a 2022 survey by Cisco of 28,000 full-time employees around the globe. Nearly 80 percent of respondents say that remote and hybrid work improved their overall well-being: that applies to 83 percent of Millennials, 82 percent of Gen Z, 76 percent of Gen Z, and 66 percent of Baby Boomers. The vast majority of respondents felt that working remotely improved their work-life balance.

Much of that improvement stemmed from saving time due to not needing to commute and having a more flexible schedule: 90 percent saved 4 to 8 hours or more per week. What did they do with that extra time? The top choice for almost half was spending more time with family, friends and pets, which certainly helped address the problem of isolation from the workplace. Indeed, three-quarters of them report that working from home improved their family relationships, and 51 percent strengthened their friendships. Twenty percent used the freed up hours for self-care.

Of the small number who report their work-life balance has not improved or even worsened, the number one reason is the difficulty of disconnecting from work, but 82 percent report that working from anywhere has made them happier. Over half say that remote work decreased their stress levels.

Other surveys back up Cisco’s findings. For example, a 2022 Future Forum survey compared knowledge workers who worked full-time in the office, in a hybrid modality, and fully remote. It found that full-time in-office workers felt the least satisfied with work-life balance, hybrid workers were in the middle, and fully remote workers felt most satisfied. The same distribution applied to questions about stress and anxiety. A mental health website called Tracking Happiness found in a 2022 survey of over 12,000 workers that fully remote employees report a happiness level about 20 percent greater than office-centric ones. Another survey by CNBC in June found that fully remote workers are more often very satisfied with their jobs than workers who are fully in-person.

Academic peer-reviewed research provides further support. Consider a 2022 study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health of bank workers who worked on the same tasks of advising customers either remotely or in-person. It found that fully remote workers experienced higher meaningfulness, self-actualization, happiness, and commitment than in-person workers. Another study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, reported that hybrid workers, compared to office-centric ones, experienced higher satisfaction with work and had 35 percent more job retention.

What about the supposed burnout crisis associated with remote work? Indeed, burnout is a concern. A survey by Deloitte finds that 77 percent of workers experienced burnout at their current job. Gallup came up with a slightly lower number of 67 percent in its survey. But guess what? Both of those surveys are from 2018, long before the era of widespread remote work.

By contrast, in a Gallup survey in late 2021, 58 percent of respondents reported less burnout. An April 2021 McKinsey survey found burnout in 54 percent of Americans and 49 percent globally. A September 2021 survey by The Hartford reported 61 percent burnout. Arguably, the increase in full or part-time remote opportunities during the pandemic helped to address feelings of burnout, rather than increasing them. Indeed, that finding aligns with the earlier surveys and peer-reviewed research suggesting remote and hybrid work improves wellbeing.

Remote work isn’t perfect – here’s how to fix its shortcomings

Still, burnout is a real problem for hybrid and remote workers, as it is for in-office workers. Employers need to offer mental health benefits with online options to help employees address these challenges, regardless of where they’re working.

Moreover, while they’re better overall for wellbeing, remote and hybrid work arrangements do have specific disadvantages around work-life separation. To address work-life issues, I advise my clients who I helped make the transition to hybrid and remote work to establish norms and policies that focus on clear expectations and setting boundaries.

For working at home and collaborating with others, there’s sometimes an unhealthy expectation that once you start your workday in your home office chair, and that you’ll work continuously while sitting there.

Some people expect their Slack or Microsoft Teams messages to be answered within an hour, while others check Slack once a day. Some believe email requires a response within three hours, and others feel three days is fine. As a result of such uncertainty and lack of clarity about what’s appropriate, too many people feel uncomfortable disconnecting and not replying to messages or doing work tasks after hours. That might stem from a fear of not meeting their boss’s expectations or not wanting to let their colleagues down.

To solve this problem, companies need to establish and incentivize clear expectations and boundaries. They should develop policies and norms around response times for different channels of communication. They also need to clarify work-life boundaries – for example, the frequency and types of unusual circumstances that will require employees to work outside of regular hours.

Moreover, for working at home and collaborating with others, there’s sometimes an unhealthy expectation that once you start your workday in your home office chair, and that you’ll work continuously while sitting there (except for your lunch break). That’s not how things work in the office, which has physical and mental breaks built in throughout the day. You took 5-10 minutes to walk from one meeting to another, or you went to get your copies from the printer and chatted with a coworker on the way.

Those and similar physical and mental breaks, research shows, decrease burnout, improve productivity, and reduce mistakes. That’s why companies should strongly encourage employees to take at least a 10-minute break every hour during remote work. At least half of those breaks should involve physical activity, such as stretching or walking around, to counteract the dangerous effects of prolonged sitting. Other breaks should be restorative mental activities, such as meditation, brief naps, walking outdoors, or whatever else feels restorative to you.

To facilitate such breaks, my client organizations such as the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute shortened hour-long meetings to 50 minutes and half-hour meetings to 25 minutes, to give everyone – both in-person and remote workers – a mental and physical break and transition time.

Very few people will be reluctant to have shorter meetings. After that works out, move to other aspects of setting boundaries and expectations. Doing so will require helping team members get on the same page and reduce conflicts and tensions. By setting clear expectations, you’ll address the biggest challenge for wellbeing for remote and hybrid work: establishing clear work-life boundaries.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy could treat Long COVID, new study shows

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been used in the past to help people with traumatic brain injury, stroke and other conditions involving wounds to the brain. Now, researchers at Shamir Medical Center in Tel Aviv are studying how it could treat Long Covid.

Long COVID is not a single disease, it is a syndrome or cluster of symptoms that can arise from exposure to SARS-CoV-2, a virus that affects an unusually large number of different tissue types. That's because the ACE2 receptor it uses to enter cells is common throughout the body, and inflammation from the immune response fighting that infection can damage surrounding tissue.

One of the most widely shared groups of symptoms is fatigue and what has come to be called “brain fog,” a difficulty focusing and an amorphous feeling of slowed mental functioning and capacity. Researchers have tied these COVID-related symptoms to tissue damage in specific sections of the brain and actual shrinkage in its size.

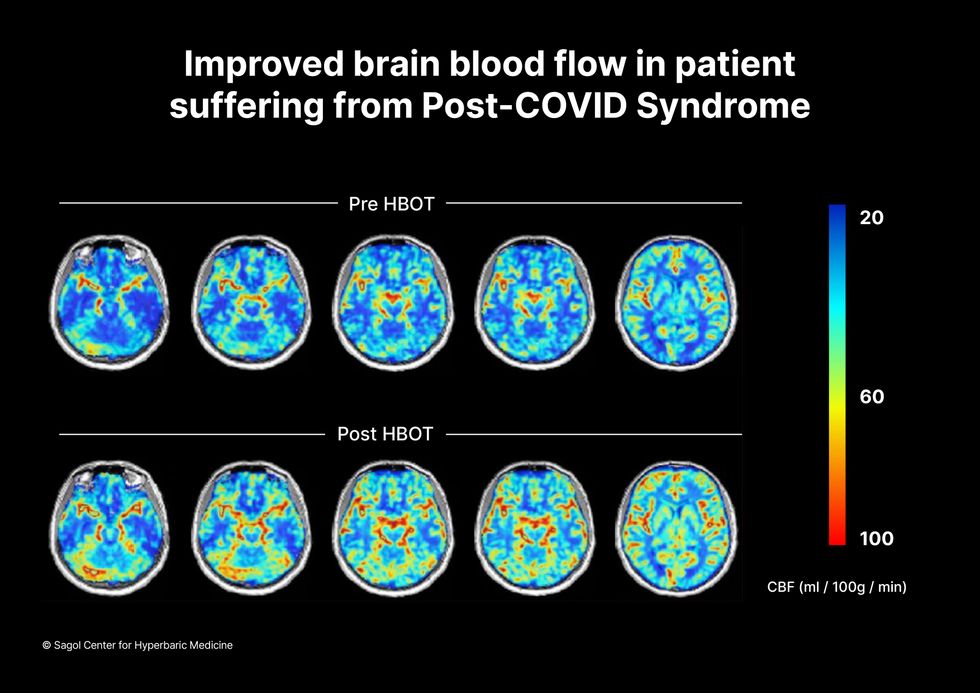

When Shai Efrati, medical director of the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research in Tel Aviv, first looked at functional magnetic resonance images (fMRIs) of patients with what is now called long COVID, he saw “micro infarcts along the brain.” It reminded him of similar lesions in other conditions he had treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). “Once we saw that, we said, this is the type of wound we can treat. It doesn't matter if the primary cause is mechanical injury like TBI [traumatic brain injury] or stroke … we know how to oxidize them.”Efrati came to HBOT almost by accident. The physician had seen how it had helped heal diabetic ulcers and improved the lives of other patients, but he was busy with his own research. Then the director of his Tel Aviv hospital threatened to shut down the small HBOT chamber unless Efrati took on administrative responsibility for it. He reluctantly agreed, a decision that shifted the entire focus of his research.

“The main difference between wounds in the leg and wounds in the brain is that one is something we can see, it's tangible, and the wound in the brain is hidden,” says Efrati. With fMRIs, he can measure how a limited supply of oxygen in blood is shuttled around to fuel activity in various parts of the brain. Years of research have mapped how specific areas of the brain control activity ranging from thinking to moving. An fMRI captures the brain area as it’s activated by supplies of oxygen; lack of activity after the same stimuli suggests damage has occurred in that tissue. Suddenly, what was hidden became visible to researchers using fMRI. It helped to make a diagnosis and measure response to treatment.

HBOT is not a single thing but rather a tool, a process or approach with variations depending on the condition being treated. It aims to increase the amount of oxygen that gets to damaged tissue and speed up healing. Regular air is about 21 percent oxygen. But inside the HBOT chamber the atmospheric pressure can be increased to up to three times normal pressure at sea level and the patient breathes pure oxygen through a mask; blood becomes saturated with much higher levels of oxygen. This can defuse through the damaged capillaries of a wound and promote healing.

The trial

Efrati’s clinical trials started in December 2020, barely a year after SARS-CoV-2 had first appeared in Israel. Patients who’d experienced cognitive issues after having COVID received 40 sessions in the chamber over a period of 60 days. In each session, they spent 90 minutes breathing through a mask at two atmospheres of pressure. While inside, they performed mental exercises to train the brain. The only difference between the two groups of patients was that one breathed pure oxygen while the other group breathed normal air. No one knew who was receiving which level of oxygen.

The results were striking. Before and after fMRIs showed significant repair of damaged tissue in the brain and functional cognition tests improved substantially among those who received pure oxygen. Importantly, 80 percent of patients said they felt back to “normal,” but Efrati says they didn't include patient evaluation in the paper because there was no baseline data to show how they functioned before COVID. After the study was completed, the placebo group was offered a new round of treatments using 100 percent oxygen, and the team saw similar results.

Scans show improved blood flow in a patient suffering from Long Covid.

Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine

Efrati's use of HBOT is part of an emerging geroscience approach to diseases associated with aging. These researchers see systems dysfunctions that are common to several diseases, such as inflammation, which has been shown to play a role in micro infarcts, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Preliminary research suggests that HBOT can retard some underlying mechanisms of aging, which might address several medical conditions. However, the drug approval process is set up to regulate individual disease, not conditions as broad as aging, and so they concentrate on treating the low hanging fruit: disorders where effective treatments currently are limited and success might be demonstrated.

The key to HBOT's effectiveness is something called the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox where a body does not react to an increase in available oxygen, only to a decrease, regardless of the starting point. That danger signal has a powerful effect on gene expression, resulting in changes in metabolism, and the proliferation of stem cells. That occurs with each cycle of 20 minutes of pure oxygen followed by 5 minutes of regular air circulating through the masks, while the chamber remains pressurized. The high levels of oxygen in the blood provide the fuel necessary for tissue regeneration.

The hyperbaric chamber that Efrati has built can hold a dozen patients and attending medical staff. Think of it as a pressurized airplane cabin, only with much more space than even in first class. In the U.S., people think of HBOT as “a sack of air or some tube that you can buy on Amazon” or find at a health spa. “That is total bullshit,” Efrati says. “It has to be a medical class center where a physician can lose their license if they are not operating it properly.”

Shai Efrati

Alexander Charney, a research psychiatrist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, calls Efrati’s study thoughtful and well designed. But it demands a lot from patients with its intense number of sessions. Those types of regimens have proven difficult to roll out to large numbers of patients. Still, the results are intriguing enough to merit additional trials.

John J. Miller, a physician and editor in chief of Psychiatric Times, has seen “many physicians that use hyperbaric oxygen for various brain disorders such as TBI.” He is intrigued by Efrati's work and believes the approach “has great potential to help patients with long COVID whose symptoms are related to brain tissue changes.”

Efrati believes so much in the power of the hyperoxic-hypoxic paradox to heal a variety of tissue injuries that he is leading the medical advisory board at Aviv Clinic, an international network of clinics that are delivering HBOT treatments based on research conducted in Israel. His goal is to silence doubters by quickly opening about 50 such clinics worldwide, based on the model of standalone dialysis clinics in the United States. Sagol Center is treating 300 patients per day, and clinics have opened in Florida and Dubai. There are plans to open another in Manhattan.

A blood test may catch colorectal cancer before it's too late

A scientist works on a blood test in the Ajay Goel Lab, one of many labs that are developing blood tests to screen for different types of cancer.

Soon it may be possible to find different types of cancer earlier than ever through a simple blood test.

Among the many blood tests in development, researchers announced in July that they have developed one that may screen for early-onset colorectal cancer. The new potential screening tool, detailed in a study in the journal Gastroenterology, represents a major step in noninvasively and inexpensively detecting nonhereditary colorectal cancer at an earlier and more treatable stage.

In recent years, this type of cancer has been on the upswing in adults under age 50 and in those without a family history. In 2021, the American Cancer Society's revised guidelines began recommending that colorectal cancer screenings with colonoscopy begin at age 45. But that still wouldn’t catch many early-onset cases among people in their 20s and 30s, says Ajay Goel, professor and chair of molecular diagnostics and experimental therapeutics at City of Hope, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit cancer research and treatment center that developed the new blood test.

“These people will mostly be missed because they will never be screened for it,” Goel says. Overall, colorectal cancer is the fourth most common malignancy, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Goel is far from the only one working on this. Dozens of companies are in the process of developing blood tests to screen for different types of malignancies.

Some estimates indicate that between one-fourth and one-third of all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers are early-onset. These patients generally present with more aggressive and advanced disease at diagnosis compared to late-onset colorectal cancer detected in people 50 years or older.

To develop his test, Goel examined publicly available datasets and figured out that changes in novel microRNAs, or miRNAs, which regulate the expression of genes, occurred in people with early-onset colorectal cancer. He confirmed these biomarkers by looking for them in the blood of 149 patients who had the early-onset form of the disease. In particular, Goel and his team of researchers were able to pick out four miRNAs that serve as a telltale sign of this cancer when they’re found in combination with each other.

The blood test is being validated by following another group of patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. “We have filed for intellectual property on this invention and are currently seeking biotech/pharma partners to license and commercialize this invention,” Goel says.

He’s far from the only one working on this. Dozens of companies are in the process of developing blood tests to screen for different types of malignancies, says Timothy Rebbeck, a professor of cancer prevention at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. But, he adds, “It’s still very early, and the technology still needs a lot of work before it will revolutionize early detection.”

The accuracy of the early detection blood tests for cancer isn’t yet where researchers would like it to be. To use these tests widely in people without cancer, a very high degree of precision is needed, says David VanderWeele, interim director of the OncoSET Molecular Tumor Board at Northwestern University’s Lurie Cancer Center in Chicago.

Otherwise, “you’re going to cause a lot of anxiety unnecessarily if people have false-positive tests,” VanderWeele says. So far, “these tests are better at finding cancer when there’s a higher burden of cancer present,” although the goal is to detect cancer at the earliest stages. Even so, “we are making progress,” he adds.

While early detection is known to improve outcomes, most cancers are detected too late, often after they metastasize and people develop symptoms. Only five cancer types have recommended standard screenings, none of which involve blood tests—breast, cervical, colorectal, lung (smokers considered at risk) and prostate cancers, says Trish Rowland, vice president of corporate communications at GRAIL, a biotechnology company in Menlo Park, Calif., which developed a multi-cancer early detection blood test.

These recommended screenings check for individual cancers rather than looking for any form of cancer someone may have. The devil lies in the fact that cancers without widespread screening recommendations represent the vast majority of cancer diagnoses and most cancer deaths.

GRAIL’s Galleri multi-cancer early detection test is designed to find more cancers at earlier stages by analyzing DNA shed into the bloodstream by cells—with as few false positives as possible, she says. The test is currently available by prescription only for those with an elevated risk of cancer. Consumers can request it from their healthcare or telemedicine provider. “Galleri can detect a shared cancer signal across more than 50 types of cancers through a simple blood draw,” Rowland says, adding that it can be integrated into annual health checks and routine blood work.

Cancer patients—even those with early and curable disease—often have tumor cells circulating in their blood. “These tumor cells act as a biomarker and can be used for cancer detection and diagnosis,” says Andrew Wang, a radiation oncologist and professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. “Our research goal is to be able to detect these tumor cells to help with cancer management.” Collaborating with Seungpyo Hong, the Milton J. Henrichs Chair and Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Pharmacy, “we have developed a highly sensitive assay to capture these circulating tumor cells.”

Even if the quality of a blood test is superior, finding cancer early doesn’t always mean it’s absolutely best to treat it. For example, prostate cancer treatment’s potential side effects—the inability to control urine or have sex—may be worse than living with a slow-growing tumor that is unlikely to be fatal. “[The test] needs to tell me, am I going to die of that cancer? And, if I intervene, will I live longer?” says John Marshall, chief of hematology and oncology at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C.

Ajay Goel Lab

A blood test developed at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston helps predict who may benefit from lung cancer screening when it is combined with a risk model based on an individual’s smoking history, according to a study published in January in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The personalized lung cancer risk assessment was more sensitive and specific than the 2021 and 2013 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force criteria.

The study involved participants from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial with a minimum of a 10 pack-year smoking history, meaning they smoked 20 cigarettes per day for ten years. If implemented, the blood test plus model would have found 9.2 percent more lung cancer cases for screening and decreased referral to screening among non-cases by 13.7 percent compared to the 2021 task force criteria, according to Oncology Times.

The conventional type of screening for lung cancer is an annual low-dose CT scan, but only a small percentage of people who are eligible will actually get these scans, says Sam Hanash, professor of clinical cancer prevention and director of MD Anderson’s Center for Global Cancer Early Detection. Such screening is not readily available in most countries.

In methodically searching for blood-based biomarkers for lung cancer screening, MD Anderson researchers developed a simple test consisting of four proteins. These proteins circulating in the blood were at high levels in individuals who had lung cancer or later developed it, Hanash says.

“The interest in blood tests for cancer early detection has skyrocketed in the past few years,” he notes, “due in part to advances in technology and a better understanding of cancer causation, cancer drivers and molecular changes that occur with cancer development.”

However, at the present time, none of the blood tests being considered eliminate the need for screening of eligible subjects using established methods, such as colonoscopy for colorectal cancer. Yet, Hanash says, “they have the potential to complement these modalities.”