Novel Technologies Could Make Coronavirus Vaccines More Stable for Worldwide Shipping

The vaccine from Pfizer will need to be stored at minus 70 degrees Celsius for worldwide distribution.

Ssendi Bosco has long known to fear the rainy season. As deputy health officer of Mubende District, a region in Central Uganda, she is only too aware of the threat that heavy storms can pose to her area's fragile healthcare facilities.

In early October, persistent rain overwhelmed the power generator that supplies electricity to most of the region, causing a blackout for three weeks. The result was that most of Mubende's vaccine supplies against diseases such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio went to waste. "The vaccines need to be constantly refrigerated, so the generator failing means that most of them are now unusable," she says.

This week, the global fight against the coronavirus pandemic received a major boost when Pfizer and their German partner BioNTech released interim results showing that their vaccine has proved more than 90 percent effective at preventing participants in their clinical trial from getting COVID-19.

But while Pfizer has already signed deals to supply the vaccine to the U.S., U.K., Canada, Japan and the European Union, Mubende's recent plight provides an indication of the challenges that distributors will face when attempting to ship a coronavirus vaccine around the globe, particularly to low-income nations.

Experts have estimated that somewhere between 12 billion and 15 billion doses will be needed to immunize the world's population against COVID-19, a staggering scale, and one that has never been attempted before. "The logistics of distributing COVID-19 vaccines have been described as one of the biggest challenges in the history of mankind," says Göran Conradson, managing director of Swedish vaccine manufacturer Ziccum.

But even these estimates do not take into account the potential for vaccine spoilage. Every year, the World Health Organization estimates that over half of the world's vaccines end up being wasted. This happens because vaccines are fragile products. From the moment they are made, to the moment they are administered, they have to be kept within a tightly controlled temperature range. Throughout the entire supply chain – transportation to an airport, the flight to another country, unloaded, distribution via trucks to healthcare facilities, and storage – they must be refrigerated at all times. This is known as the cold chain, and one tiny slip along the way means the vaccines are ruined.

"It's a chain, and any chain is only as strong as its weakest link," says Asel Sartbaeva, a chemist working on vaccine technologies at the University of Bath in the U.K.

For COVID-19, the challenge is even greater because some of the leading vaccine candidates need to be kept at ultracold temperatures. Pfizer's vaccine, for example, must be kept at -70 degrees Celsius, the kind of freezer capabilities rarely found outsides of specialized laboratories. Transporting such a vaccine across North America and Europe will be difficult enough, but supplying it to some of the world's poorest nations in Asia, Africa and South America -- where only 10 percent of healthcare facilities have reliable electricity -- might appear virtually impossible.

But technology may be able to come to the rescue.

Making Vaccines Less Fragile

Just as the world's pharmaceutical companies have been racing against the clock to develop viable COVID-19 vaccine candidates, scientists around the globe have been hastily developing new technologies to try and make vaccines less fragile. Some approaches involve various chemicals that can be added to the vaccine to make them far more resilient to temperature fluctuations during transit, while others focus on insulated storage units that can maintain the vaccine at a certain temperature even if there is a power outage.

Some of these concepts have already been considered for several years, but before COVID-19 there was less of a commercial incentive to bring them to market. "We never felt that there is a need for an investment in this area," explains Sam Kosari, a pharmacist at the University of Canberra, who researches the vaccine cold chain. "Some technologies were developed then to assist with vaccine transport in Africa during Ebola, but since that outbreak was contained, there hasn't been any serious initiative or reward to develop this technology further."

In her laboratory at the University of Bath, Sartbaeva is using silica - the main constituent of sand – to encase the molecular components within a vaccine. Conventional vaccines typically contain protein targets from the virus, which the immune system learns to recognize. However, when they are exposed to temperature changes, these protein structures degrade, and lose their shape, making the vaccine useless. Sartbaeva compares this to how an egg changes its shape and consistency when it is boiled.

When silica is added to a vaccine, it molds to each protein, forming little protective cages around them, and thus preventing them from being affected by temperature changes. "The whole idea is that if we can create a shell around each protein, we can protect it from physically unravelling which is what causes the deactivation of the vaccine," she says.

Other scientists are exploring similar methods of making vaccines more resilient. Researchers at the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford recently conducted a clinical trial in which they added carbohydrates to a dengue vaccine, to assess whether it became easier to transport.

Both research groups are now hoping to collaborate with the COVID-19 vaccine candidates being developed by AstraZeneca and Imperial College, assuming they become available in 2021.

"It's good we're all working on this big problem, as different methods could work better for different types of COVID-19 vaccines," says Sartbaeva. "I think it will be needed."

Next-Generation Vaccine Technology

While these different technologies could be utilized to try and protect the first wave of COVID-19 vaccines, efforts are also underway to develop completely new methods of vaccination. Much of this research is still in its earliest stages, but it could yield a second generation of COVID-19 vaccine candidates in 2022 and beyond.

"After the first round of mass vaccination, we could well observe regional outbreaks of the disease appearing from time to time in the coming years," says Kosari. "This is the time where new types of vaccines could be helpful."

One novel method being explored by Ziccum and others is dry powder vaccines. The idea is to spray dry the final vaccine into a powder form, where it is more easily preserved and does not require any special cooling while being transported or stored. People then receive the vaccine by inhaling it, rather than having it injected into their bloodstream.

Conradson explains that the concept of dry powder vaccines works on the same principle as dried food products. Because there is no water involved, the vaccine's components are far less affected by temperature changes. "It is actually the water that leads to the destruction of potency of a vaccine when it gets heated," he says. "We're looking to develop a dry powder vaccine for COVID-19 but this will be a second-generation vaccine. At the moment there are more than 200 first-generation candidates, all of which are using conventional technologies due to the timeframe pressures, which I think was the correct decision."

Dry powder COVID-19 vaccines could also be combined with microneedle patches, to allow people to self-administer the vaccine themselves in their own home. Microneedles are miniature needles – measured in millionths of a meter – which are designed to deliver medicines through the skin with minimal pain. So far, they have been used mainly in cosmetic products, but many scientists are working to use them to deliver drugs or vaccines.

At Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Mark Prausnitz is leading a couple of projects looking at incorporating COVID-19 vaccines into microneedle patches with the hope of running some early-stage clinical trials over the next couple of years. "The advantage is that they maintain the vaccine in a stable, dry state until it dissolves in the skin," he explains.

Prausnitz and others believe that once the first generation of COVID-19 vaccines become available, biotech and pharmaceutical companies will show more interest in adapting their products so they can be used in a dried form or with a microneedle patch. "There is so much pressure to get the COVID vaccine out that right now, vaccine developers are not interested in incorporating a novel delivery method," he says. "That will have to come later, once the pressure is lessened."

The Struggle of Low-Income Nations

For low-income nations, time will only tell whether technological advancements can enable them to access the first wave of licensed COVID-19 vaccines. But reports already suggest that they are in danger of becoming an afterthought in the race to procure vaccine supplies.

While initiatives such as COVAX are attempting to make sure that vaccine access is equitable, high and middle-income countries have already inked deals to secure 3.8 billion doses, with options for another 5 billion. One particularly sobering study by the Duke Global Health Innovation Center has suggested that such hoarding means many low-income nations may not receive a vaccine until 2024.

For Bosco and the residents of Mubende District in Uganda, all they can do is wait. In the meantime, there is a more pressing problem: fixing their generators. "We hope that we can receive a vaccine," she says. "But the biggest problem will be finding ways to safely store it. Right now we cannot keep any medicines or vaccines in the conditions they need, because we don't have the funds to repair our power generators."

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

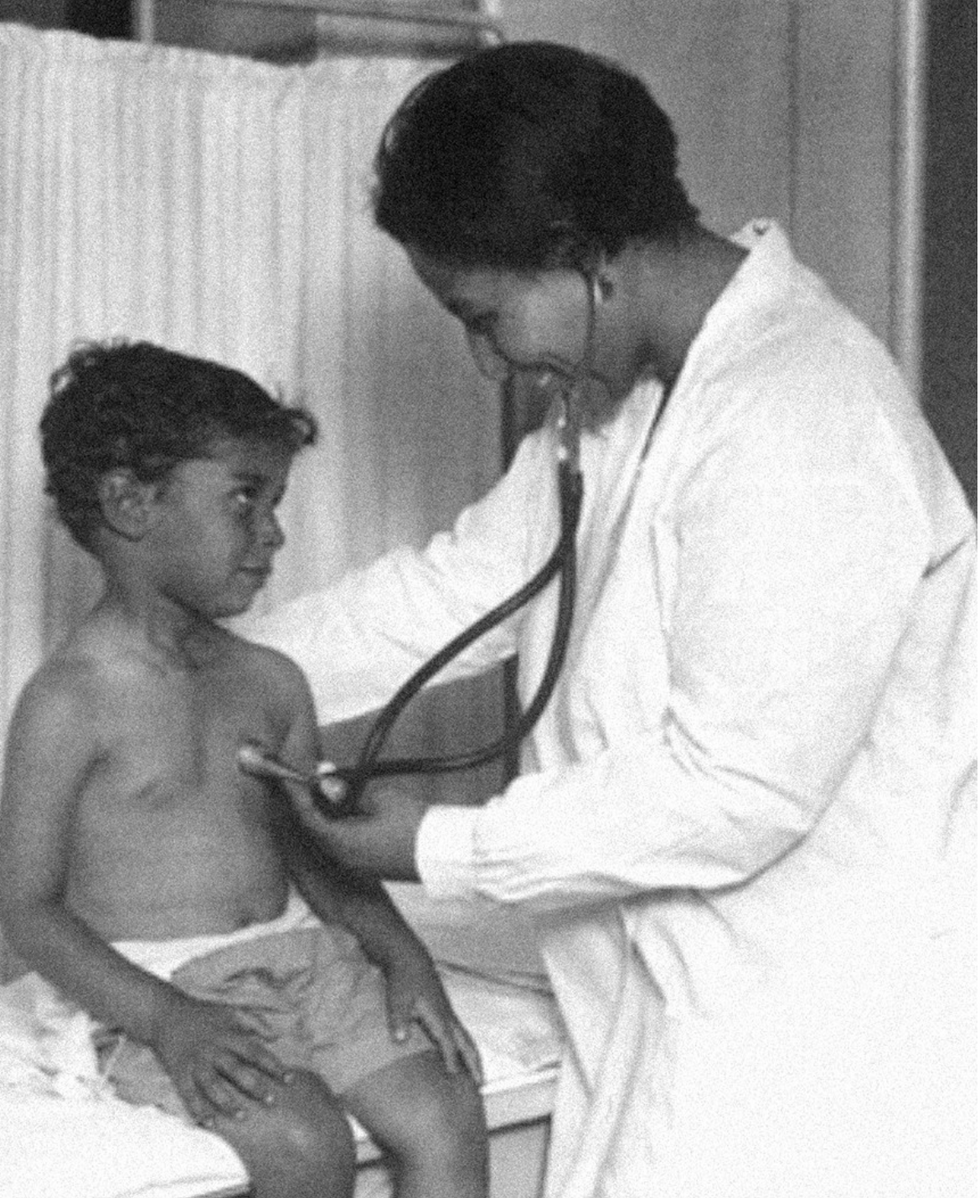

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

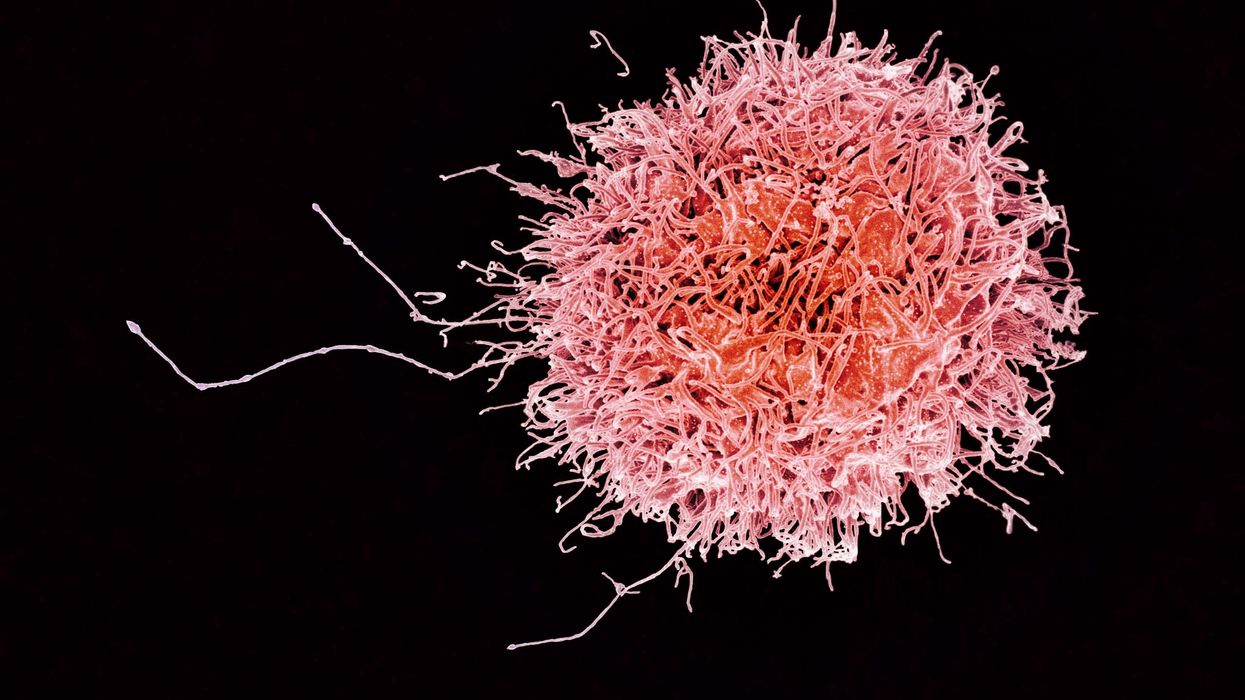

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business