Are the gains from gain-of-function research worth the risks?

Gain-of-function research can make pathogens more infectious and deadly. It also enables scientists to prepare remedies in advance.

Scientists have long argued that gain-of-function research, which can make viruses and other infectious agents more contagious or more deadly, was necessary to develop therapies and vaccines to counter the pathogens in case they were used for biological warfare. As the SARS-CoV-2 origins are being investigated, one prominent theory suggests it had leaked from a biolab that conducted gain-of-function research, causing a global pandemic that claimed nearly 6.9 million lives. Now some question the wisdom of engaging in this type of research, stating that the risks may far outweigh the benefits.

“Gain-of-function research means genetically changing a genome in a way that might enhance the biological function of its genes, such as its transmissibility or the range of hosts it can infect,” says George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School. This can occur through direct genetic manipulation as well as by encouraging mutations while growing successive generations of micro-organism in culture. “Some of these changes may impact pathogenesis in a way that is hard to anticipate in advance,” Church says.

In the wake of the global pandemic, the pros and cons of gain-of-function research are being fiercely debated. Some scientists say this type of research is vital for preventing future pandemics or for preparing for bioweapon attacks. Others consider it another disaster waiting to happen. The Government Accounting Office issued a report charging that a framework developed by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) provided inadequate oversight of this potentially deadly research. There’s a movement to stop it altogether. In January, the Viral Gain-of-Function Research Moratorium Act (S. 81) was introduced into the Senate to cease awarding federal research funding to institutions doing gain-of-function studies.

While testifying before the House COVID Origins Select Committee on March 8th, Robert Redfield, former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said that COVID-19 may have resulted from an accidental lab leak involving gain-of-function research. Redfield said his conclusion is based upon the “rapid and high infectivity for human-to-human transmission, which then predicts the rapid evolution of new variants.”

“It is a very, very, very small subset of life science research that could potentially generate a potential pandemic pathogen,” said Gerald Parker, associate dean for Global One Health at Texas A&M University.

“In my opinion,” Redfield continues, “the COVID-19 pandemic presents a case study on the potential dangers of such research. While many believe that gain-of-function research is critical to get ahead of viruses by developing vaccines, in this case, I believe that was the exact opposite.” Consequently, Redfield called for a moratorium on gain-of-function research until there is consensus about the value of such risky science.

What constitutes risky?

The Federal Select Agent Program lists 68 specific infectious agents as risky because they are either very contagious or very deadly. In order to work with these 68 agents, scientists must register with the federal government. Meanwhile, research on deadly pathogens that aren’t easily transmitted, or pathogens that are quite contagious but not deadly, can be conducted without such oversight. “If you’re not working with select agents, you’re not required to register the research with the federal government,” says Gerald Parker, associate dean for Global One Health at Texas A&M University. But the 68-item list may not have everything that could possibly become dangerous or be engineered to be dangerous, thus escaping the government’s scrutiny—an issue that new regulations aim to address.

In January 2017, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued additional guidance. It required federal departments and agencies to follow a series of steps when reviewing proposed research that could create, transfer, or use potential pandemic pathogens resulting from the enhancement of a pathogen’s transmissibility or virulence in humans.

In defining risky pathogens, OSTP included viruses that were likely to be highly transmissible and highly virulent, and thus very deadly. The Proposed Biosecurity Oversight Framework for the Future of Science, outlined in 2023, broadened the scope to require federal review of research “that is reasonably anticipated to enhance the transmissibility and/or virulence of any pathogen” likely to pose a threat to public health, health systems or national security. Those types of experiments also include the pathogens’ ability to evade vaccines or therapeutics, or diagnostic detection.

However, Parker says that dangers of generating a pandemic-level germ are tiny. “It is a very, very, very small subset of life science research that could potentially generate a potential pandemic pathogen.” Since gain-of-function guidelines were first issued in 2017, only three such research projects have met those requirements for HHS review. They aimed to study influenza and bird flu. Only two of those projects were funded, according to the NIH Office of Science Policy. For context, NIH funded approximately 11,000 of the 54,000 grant applications it received in 2022.

Guidelines governing gain-of-function research are being strengthened, but Church points out they aren’t ideal yet. “They need to be much clearer about penalties and avoiding positive uses before they would be enforceable.”

What do we gain from gain-of-function research?

The most commonly cited reason to conduct gain-of-function research is for biodefense—the government’s ability to deal with organisms that may pose threats to public health.

In the era of mRNA vaccines, the advance preparedness argument may be even less relevant.

“The need to work with potentially dangerous viruses is central to our preparedness,” Parker says. “It’s essential that we know and understand the basic biology, microbiology, etc. of some of these dangerous pathogens.” That includes increasing our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms by which a virus could become a sustained threat to humans. “Knowing that could help us detect [risks] earlier,” Parker says—and could make it possible to have medical countermeasures, like vaccines and therapeutics, ready.

Most vaccines, however, aren’t affected by this type of research. Essentially, scientists hope they will never need to use it. Moreover, Paul Mango, HSS former deputy chief of staff for policy, and author of the 2022 book Warp Speed, says he believes that in the era of mRNA vaccines, the advance preparedness argument may be even less relevant. “That’s because these vaccines can be developed and produced in less than 12 months, unlike traditional vaccines that require years of development,” he says.

Can better oversight guarantee safety?

Another situation, which Parker calls unnecessarily dangerous, is when regulatory bodies cannot verify that the appropriate biosafety and biosecurity controls are in place.

Gain-of-function studies, Parker points out, are conducted at the basic research level, and they’re performed in high-containment labs. “As long as all the processes, procedures and protocols are followed and there’s appropriate oversight at the institutional and scientific level, it can be conducted safely.”

Globally, there are 69 Biosafety Level 4 (BSL4) labs operating, under construction or being planned, according to recent research from King’s College London and George Mason University for Global BioLabs. Eleven of these 18 high-containment facilities that are planned or under construction are in Asia. Overall, three-quarters of the BSL4 labs are in cities, increasing public health risks if leaks occur.

Researchers say they are confident in the oversight system for BSL4 labs within the U.S. They are less confident in international labs. Global BioLabs’ report concurs. It gives the highest scores for biosafety to industrialized nations, led by France, Australia, Canada, the U.S. and Japan, and the lowest scores to Saudi Arabia, India and some developing African nations. Scores for biosecurity followed similar patterns.

“There are no harmonized international biosafety and biosecurity standards,” Parker notes. That issue has been discussed for at least a decade. Now, in the wake of SARS and the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists and regulators are likely to push for unified oversight standards. “It’s time we got serious about international harmonization of biosafety and biosecurity standards and guidelines,” Parker says. New guidelines are being worked on. The National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) outlined its proposed recommendations in the document titled Proposed Biosecurity Oversight Framework for the Future of Science.

The debates about whether gain-of-function research is useful or poses unnecessary risks to humanity are likely to rage on for a while. The public too has a voice in this debate and should weigh in by communicating with their representatives in government, or by partaking in educational forums or initiatives offered by universities and other institutions. In the meantime, scientists should focus on improving the research regulations, Parker notes. “We need to continue to look for lessons learned and for gaps in our oversight system,” he says. “That’s what we need to do right now.”

With this new technology, hospitals and pharmacies could make vaccines and medicines onsite

New research focuses on methods that could change medicine-making worldwide. The scientists propose bursting cells open, removing their DNA and using the cellular gears inside to make therapies.

Most modern biopharmaceutical medicines are produced by workhorse cells—typically bacterial but sometimes mammalian. The cells receive the synthesizing instructions on a snippet of a genetic code, which they incorporate into their DNA. The cellular machinery—ribosomes, RNAs, polymerases, and other compounds—read and use these instructions to build the medicinal molecules, which are harvested and administered to patients.

Although a staple of modern pharma, this process is complex and expensive. One must first insert the DNA instructions into the cells, which they may or may not uptake. One then must grow the cells, keeping them alive and well, so that they produce the required therapeutics, which then must be isolated and purified. To make this at scale requires massive bioreactors and big factories from where the drugs are distributed—and may take a while to arrive where they’re needed. “The pandemic showed us that this method is slow and cumbersome,” says Govind Rao, professor of biochemical engineering who directs the Center for Advanced Sensor Technology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). “We need better methods that can work faster and can work locally where an outbreak is happening.”

Rao and his team of collaborators, which spans multiple research institutions, believe they have a better approach that may change medicine-making worldwide. They suggest forgoing the concept of using living cells as medicine-producers. Instead, they propose breaking the cells and using the remaining cellular gears for assembling the therapeutic compounds. Instead of inserting the DNA into living cells, the team burst them open, and removed their DNA altogether. Yet, the residual molecular machinery of ribosomes, polymerases and other cogwheels still functioned the way it would in a cell. “Now if you drop your DNA drug-making instructions into that soup, this machinery starts making what you need,” Rao explains. “And because you're no longer worrying about living cells, it becomes much simpler and more efficient.” The collaborators detail their cell-free protein synthesis or CFPS method in their recent paper published in preprint BioAxiv.

While CFPS does not use living cells, it still needs the basic building blocks to assemble proteins from—such as amino acids, nucleotides and certain types of enzymes. These are regularly added into this “soup” to keep the molecular factory chugging. “We just mix everything in as a batch and we let it integrate,” says James Robert Swartz, professor of chemical engineering and bioengineering at Stanford University and co-author of the paper. “And we make sure that we provide enough oxygen.” Rao likens the process to making milk from milk powder.

For a variety of reasons—from the field’s general inertia to regulatory approval hurdles—the method hasn’t become mainstream. The pandemic rekindled interest in medicines that can be made quickly and easily, so it drew more attention to the technology.

The idea of a cell-free protein synthesis is older than one might think. Swartz first experimented with it around 1997, when he was a chemical engineer at Genentech. While working on engineering bacteria to make pharmaceuticals, he discovered that there was a limit to what E. coli cells, the workhorse darling of pharma, could do. For example, it couldn’t grow and properly fold some complex proteins. “We tried many genetic engineering approaches, many fermentation, development, and environmental control approaches,” Swartz recalls—to no avail.

“The organism had its own agenda,” he quips. “And because everything was happening within the organism, we just couldn't really change those conditions very easily. Some of them we couldn’t change at all—we didn’t have control.”

It was out of frustration with the defiant bacteria that a new idea took hold. Could the cells be opened instead, so that the protein-forming reactions could be influenced more easily? “Obviously, we’d lose the ability for them to reproduce,” Swartz says. But that also meant that they no longer needed to keep the cells alive and could focus on making the specific reactions happen. “We could take the catalysts, the enzymes, and the more complex catalysts and activate them, make them work together, much as they would in a living cell, but the way we wanted.”

In 1998, Swartz joined Stanford, and began perfecting the biochemistry of the cell-free method, identifying the reactions he wanted to foster and stopping those he didn’t want. He managed to make the idea work, but for a variety of reasons—from the field’s general inertia to regulatory approval hurdles—the method hasn’t become mainstream. The pandemic rekindled interest in medicines that can be made quickly and easily, so it drew more attention to the technology. For their BioArxiv paper, the team tested the method by growing a specific antiviral protein called griffithsin.

First identified by Barry O’Keefe at National Cancer Institute over a decade ago, griffithsin is an antiviral known to interfere with many viruses’ ability to enter cells—including HIV, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, MERS and others. Originally isolated from the red algae Griffithsia, it works differently from antibodies and antibody cocktails.

Most antiviral medicines tend to target the specific receptors that viruses use to gain entry to the cells they infect. For example, SARS-CoV-2 uses the infamous spike protein to latch onto the ACE2 receptor of mammalian cells. The antibodies or other antiviral molecules stick to the spike protein, shutting off its ability to cling onto the ACE2 receptors. Unfortunately, the spike proteins mutate very often, so the medicines lose their potency. On the contrary, griffithsin has the ability to cling to the different parts of viral shells called capsids—namely to the molecules of mannose, a type of sugar. That extra stuff, glued all around the capsid like dead weight, makes it impossible for the virus to squeeze into the cell.

“Every time we have a vaccine or an antibody against a specific SARS-CoV-2 strain, that strain then mutates and so you lose efficacy,” Rao explains. “But griffithsin molecules glom onto the viral capsid, so the capsid essentially becomes a sticky mess and can’t enter the cell.” Mannose molecules also don’t mutate as easily as viruses’ receptors, so griffithsin-based antivirals do not have to be constantly updated. And because mannose molecules are found on many viruses’ capsids, it makes griffithsin “a universal neutralizer,” Rao explains.

“When griffithsin was discovered, we recognized that it held a lot of promise as a potential antiviral agent,” O’Keefe says. In 2010, he published a paper about griffithsin efficacy in neutralizing viruses of the corona family—after the first SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, the scientific community was interested in such antivirals. Yet, griffithsin is still not available as an off-the-shelf product. So during the Covid pandemic, the team experimented with synthesizing griffithsin using the cell-free production method. They were able to generate potent griffithsin in less than 24 hours without having to grow living cells.

The antiviral protein isn't the only type of medicine that can be made cell-free. The proteins needed for vaccine production could also be made the same way. “Such portable, on-demand drug manufacturing platforms can produce antiviral proteins within hours, making them ideal for combating future pandemics,” Rao says. “We would be able to stop the pandemic before it spreads.”

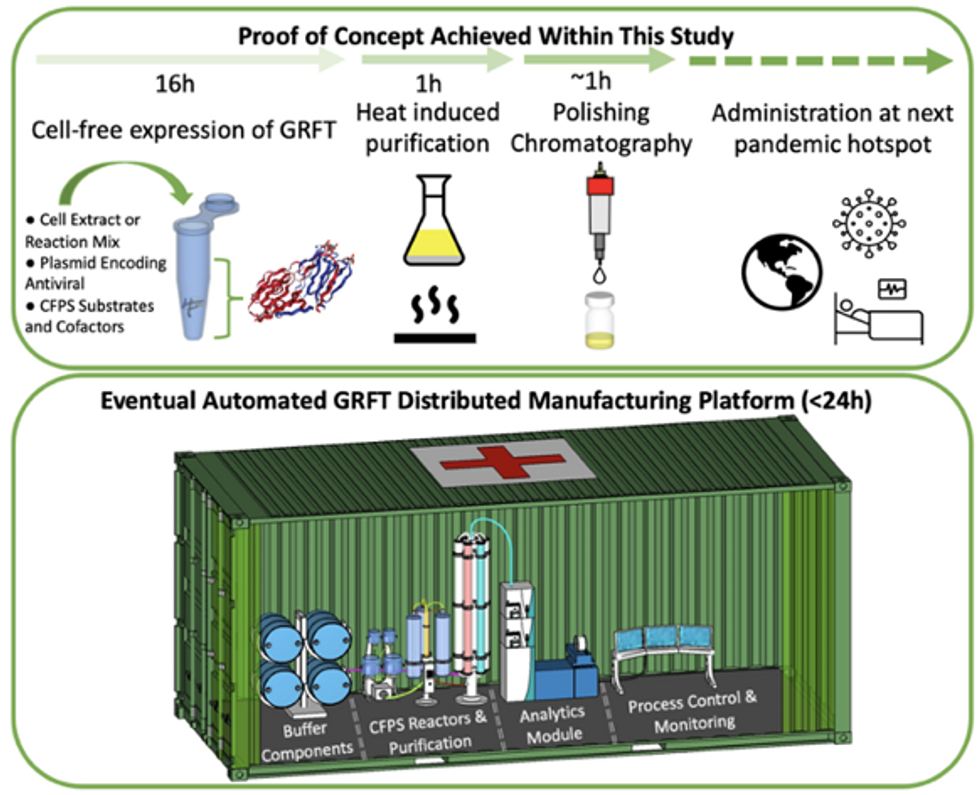

Top: Describes the process used in the study. Bottom: Describes how the new medicines and vaccines could be made at the site of a future viral outbreak.

Image courtesy of Rao and team, sourced from An approach to rapid distributed manufacturing of broad spectrumanti-viral griffithsin using cell-free systems to mitigate pandemics.

Rao’s idea is to perfect the technology to the point that any hospital or pharmacy can load up the media containing molecular factories, mix up the required amino acids, nucleotides and enzymes, and harvest the meds within hours. That will allow making medicines onsite and on demand. “That would be a self-contained production unit, so that you could just ship the production wherever the pandemic is breaking out,” says Swartz.

These units and the meds they produce, will, of course, have to undergo rigorous testing. “The biggest hurdles will be validating these against conventional technology,” Rao says. The biotech industry is risk-averse and prefers the familiar methods. But if this approach works, it may go beyond emergency situations and revolutionize the medicine-making paradigm even outside hospitals and pharmacies. Rao hopes that someday the method might become so mainstream that people may be able to buy and operate such reactors at home. “You can imagine a diabetic patient making insulin that way, or some other drugs,” Rao says. It would work not unlike making baby formula from the mere white powder. Just add water—and some oxygen, too.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

These doctors have a heart for recycling

In the U.S. and Europe, it is illegal to reuse pacemakers and other implants. Therefore, cardiologists export them to the global South where they save the lives of people of all ages.

This is part 3 of a three part series on a new generation of doctors leading the charge to make the health care industry more sustainable - for the benefit of their patients and the planet. Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

One could say that over 400 people owe their life to the fact that Carsten Israel fell in love. Twenty years ago, as a young doctor in Frankfurt, Germany, he began to court an au pair from Kenya, Elisabeth, his now-wife of 13 years with whom he has three children. When the couple started visiting her parents in Kenya, Israel wanted to check out the local hospitals, “just out of professional curiosity,“ says the cardiologist, who is currently the head doctor at the Clinic for Interior Medicine in Bielefeld. “I was completely shocked.“

Often he observed there were no doctors in the E.R.s, and hte nurses could render only basic first aid. “When somebody fell into a coma, they fell into a coma,“ Israel remembers. “There weren’t even any defibrillators to restart a patient’s heart,” while defibrillators are standard equipment in most clinics in the U.S. and Europe as lifesaving devices. When Israel finally visited the largest and most modern hospital in Nairobi, he found it better equipped but he learned that its services were only available to patients who could afford them. The cardiologist there had a drawer full of petitions from patients with heart ailments who couldn’t afford lifesaving surgery. Even two decades ago, a pacemaker cost $5,000 in Kenya, which made it unaffordable for most Kenyans who earn an average of $600 per month.

Since 2003, Israel and a team of two doctors and two nurses visit Kenya and Zambia once or twice a year to implant German pacemakers for free. Notably, the pacemakers and defibrillators Israel exports to Africa would end up in the landfill in Germany. Clinics have to pay for specialized services to dispose of this medical equipment. “In Germany, I could go to jail if I used a defibrillator that is one day past its expiration date,“ Israel says, “but in Kenya, people don’t have the money for the cheapest model. What nonsense to throw this precious medical equipment away while people in poorer countries die because they desperately need it.“

Israel works at the breakpoint between the laws in a wealthy country like Germany and the reality in the global South. The U.S. and most European countries have strict laws that ban the reuse of medical implants and enforce strict expiration dates for medical equipment. “But if a pacemaker is a few days past its expiration date, it still works perfectly fine,“ Israel says. “And it also happens that we implant a pacemaker and five months later it turns out that the patient needs a different kind. Then we replace it and we’d have to trash the first one in Germany, though it could easily run another 12 years.“

“If we get this right, we have lots of devices we can implant, hips and knees, etcetera. Where this will lead is limitless," says Eva Kline Rogers, the program coordinator for My Heart, Your Heart.

Israel has been collecting donations of pacemakers and defibrillators from manufacturers but also from other doctors and from funeral homes for his nonprofit Pacemakers for East Africa since 2003. Most funeral homes in the U.S. and Europe are legally obliged to remove pacemakers from the dead before cremation. “Most pacemakers survive their owners,“ says Israel. He sterilizes the pacemakers and finds them a new life in East Africa. Studies show that reused pacemakers carry no greater risk for the patients than new ones.

In the U.S., University of Michigan professor Thomas Crawford heads up a similar initiative, My Heart, Your Heart. “Each year 1 to 2 million individuals worldwide die due to a lack of access to pacemakers and defibrillators,” the organization notes on its website. The nonprofit was founded in 2009, but it took four years for the doctors to get permission from the FDA to export pacemakers. Since receiving permission, the organization has sent dozens of devices to the Philippines, Haiti, Venezuela, Kenya, Sierra Leone and Ukraine. “We were the first doctors ever to implant a pacemaker in Sierra Leone in 2018,” says Crawford, who has traveled extensively to most of the recipient countries.

Even individuals can donate their pacemakers; the organization offers a prepaid envelope. “My mother recently passed and she donated her device,” says Tina Alexandris-Souphis, one of the doctors at University of Michigan who collaborates on My Heart, Your Heart. The organization works with World Medical Relief and the U.K. based charity Pace4Life to maintain a registry of the most urgent patients and send devices to where they are needed the most.

My Heart, Your Heart is also conducting a randomized controlled trial to provide further evidence that reused pacemakers pose no additional risk. “Our vision is that we establish this is safe and create a blueprint for organizations around the world to safely reuse these devices instead of them being thrown in the trash,” says Eva Kline Rogers, the program’s coordinator. “If we get this right, we have lots of devices we can implant, hips and knees, etc. Where this will lead is limitless.” She points out that in addition to receiving the donated devices, the doctors in the global South also benefit from the expertise of renowned cardiologists, such as Crawford, who sometimes advise them in complex cases.

And Adrian Baranchuk, a Canadian doctor at the Kingston General Hospital at the Queen’s University, regularly travels through South America with his “cardiology van” to help villagers in remote areas with heart problems.

Israel says that he’s been accused of racism, in thinking that these pacemakers are suitable for those in the global South - many of whom are people of color - even though officials in wealthier countries consider them to be trash. The cardiologist counters such criticism with stories about desperate need of his patients. At his first medical visit to Nairobi that he organized with a local cardiologist, six patients were waiting for him. “In Germany, they would all be considered emergencies,” Israel says. One eighty-year old grandmother had a heartrate of 18. “I’ve never before seen anything like this,” Israel exclaims. “At first I thought I couldn’t find her pulse before I realized that her heart was only beating once every three seconds.” After the surgery, she got up, dressed herself and hurriedly packed her bag, explaining she had a ton of work to accomplish. Her family was in disbelief, Israel says. “They told me she had been bedridden for five years because as soon as she tried to get up she would faint.”

Israel has been accused of racism, in thinking that these pacemakers are suitable for those in the global South even though they're considered to be trash by officials in wealthier countries. The cardiologist counters such criticism with stories about desperate need of his patients.

Carsten Israel

The hospital in Nairobi where Israel conducts the surgeries, charges patients $200 for the use of its facilities. If patients can’t afford that sum, Israel will pay it from the funds of his nonprofit. For some people, $200 far exceeds their resources. Once, a family from the extremely poor Northern region of Kenya told him they couldn’t afford the $3 for the bus ride to Nairobi. Israel suspected this was a pretense because they were afraid of the surgery and agreed to reimburse the $3, “but when they came, they were wearing rags and were so rail-thin, I understood that they really needed every cent they had for food.”

Israel is a renowned cardiologists in Germany. And yet, he considers his work in East Africa to be particularly meaningful. “Generally, most patients in Germany will get the treatment they need,” he says, “and I never before experienced that people have an illness that is easily curable but simply won’t be treated.” He also feels a heavy responsibility. Many patients have his personal cell phone and call him when they have problems or good news about how they’re doing.

Some of those progress reports come much faster than in Israel’s home country. Before he implanted a pacemaker in a tall Massai in Kenya, the man had been picked on by his family because he wouldn’t help much with the hard work on the family peanut farm. “When I examined him, he had a pulse of 40,” Israel says. “It’s a miracle he was even standing upright, let alone hauling heavy bags.” After the surgery, Israel advised his patient to stay the night for observation, but the patient couldn’t wait to leave. Two hours later, he returned, covered in sweat. He’d been running sprints with his brothers to test the new device. Israel shakes his head. In Germany, it would be unthinkable for a patient to engage in athletics immediately after surgery. But the patient was exuberant: “I was the fastest!”

The success stories are notable partly because the challenges remain so steep. In Zambia, for instance, there is a single cardiologist; she determined to become one after losing her younger sister to an easily curable heart disease. Often, the hospitals not only lack pacemakers but also sterile surgery equipment, antibiotics and other essential material. Therefore, Israel and his team import everything they need for the surgeries, including medication. If necessary, they improvise. “I’ve done surgery with a desk lamp hanging from the ceiling by threads,” Israel says. He already knows that he will need to return to Kenya in six months to replace the pacemaker of one of his patients and replace the batteries in others. If he doesn’t travel, lives are at risk.