The Age of DNA-Based Dating Is Here

A woman gives a DNA sample at a Pheramor-sponsored event.

Brittany Barreto first got the idea to make a DNA-based dating platform nearly 10 years ago when she was in a college seminar on genetics. She joked that it would be called GeneHarmony.com.

Pheramor and startups, like DNA Romance and Instant Chemistry, both based in Canada, claim to match you to a romantic partner based on your genetics.

The idea stuck with her while she was getting her PhD in genetics at Baylor College of Medicine, and in March 2018, she launched Pheramor, a dating app that measures compatibility based on physical chemistry and what the company calls "social alignment."

"I wanted to use genetics and science to help people connect more. Our world is so hungry for connection," says Barreto, who serves as Pheramor's CEO.

With the direct-to-consumer genetic testing market booming, more and more companies are looking to capitalize on the promise of DNA-based services. Pheramor and startups, like DNA Romance and Instant Chemistry, both based in Canada, claim to match you to a romantic partner based on your genetics. It's an intriguing alternative to swiping left or right in hopes of finding someone you're not only physically attracted to but actually want to date. Experts say the science behind such apps isn't settled though.

For $40, Pheramor sends you a DNA kit to swab the inside of your cheek. After you mail in your sample, Pheramor analyzes your saliva for 11 different HLA genes, a fraction of the more than 200 genes that are thought to make up the human HLA complex. These genes make proteins that regulate the immune system by helping protect against invading pathogens.

It takes three to four weeks to get the results backs. In the meantime, users can still download the app and start using it before their DNA results are ready. The app asks users to link their social media accounts, which are fed into an algorithm that calculates a "social alignment." The algorithm takes into account the hashtags you use, your likes, check-ins, posts, and accounts you follow on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

The DNA test results and social alignment algorithm are used to calculate a compatibility percentage between zero and 100. Barreto said she couldn't comment on how much of that score is influenced by the algorithm and how much comes from what the company calls genetic attraction. "DNA is not destiny," she says. "It's not like you're going to swab and I'll send you your soulmate."

Despite its name, Pheramor doesn't actually measure pheromones, chemicals released by animals that affect the behavior of others of the same species. That's because human pheromones have yet to be identified, though they've been discovered throughout the animal kingdom in moths, mice, rabbits, pigs, and many other insects and mammals. The HLA genes Pheramor analyzes instead are the human version of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), a gene group found in many species.

The connection between HLA type and attraction goes back to the 1970s, when researchers found that inbred male mice preferred to mate with female mice with a different MHC rather than inbred female mice with similar immune system genes. The researchers concluded that this mating preference was linked to smell. The idea is that choosing a mate with different MHC genes gives animals an evolutionary advantage in terms of immune system defense.

The couples who had more dissimilar HLA types reported a more satisfied sex life and satisfied partnership, but it was a small effect.

In the 1990s, Swiss scientists wanted to see if body odor also had an effect on human attraction. In a famous experiment known as the "sweaty T-shirt study", they recruited 49 women to sniff sweaty, unwashed T-shirts from 44 men and put each in a box with a smelling hole and describe the odors of every shirt. The study found that women preferred the scents of T-shirts worn by men who were immunologically different from them compared to men whose HLA genes were similar to their own.

"The idea is, if you are very similar with your partner in HLA type then your offspring is similar in terms of HLA. This reduces your resistance against pathogens," says Illona Croy, a psychologist at the Technical University of Dresden who has studied HLA type in relation to sexual attraction in humans.

In a 2016 study Pheramor cites on its website, Croy and her colleagues tested the HLA types of 250 couples—all of them university students—and asked them how satisfied they were with their partnerships, with their sex lives, and with the odors of their partners. The couples who had more dissimilar HLA types reported a more satisfied sex life and satisfied partnership, but Croy cautions that it was a small effect. "It's not like they were super satisfied or not satisfied at all. It's a slight difference," she says.

Croy says we're much more likely to choose a partner based on appearance, sense of humor, intelligence and common interests.

Other studies have reported no preference for HLA difference in sexual attraction. Tristram Wyatt, a zoologist at the University of Oxford in the U.K. who studies animal pheromones, says it's been difficult to replicate the original T-shirt study. And one of the caveats of the original study is that women who were taking birth control pills preferred men who were more immunologically similar.

"Certainly, we learn to really like the smell of our partners," Wyatt says. "Whether it's the reason for choosing them in the first place, we really don't know."

Wyatt says he's skeptical of DNA-based dating apps because there are many subtypes of HLA genes, meaning there's a fairly low chance that your HLA type and your romantic partner's would be an exact match, anyway. It's why finding a suitable match for a bone marrow transplant is difficult; a donor's HLA type has to be the same as the recipient's.

"What it means is that since we're all different, it's hard statistically to say who the best match will be," he says.

DNA-based dating apps haven't yet gone mainstream, but some people seem willing to give them a try. Since Pheramor's launch a little over a year ago, about 10,000 people have signed up to use the app, about half of which have taken the DNA test, Barreto says. By comparison, an estimated 50 million people use Tinder, which has been around since 2012, and about 40 million people are on Bumble, which was released in 2014.

In April, Barreto launched a second service, this one for couples, called WeHaveChemistry.com. A $139 kit includes two genetic tests, one for you and your partner, and a detailed DNA report on your sexual compatibility.

Unlike the Phermor app, WeHaveChemistry doesn't provide users with a numeric combability score but instead makes personalized recommendations based on your genetic results. For instance, if the DNA test shows that your HLA genes are similar, Barreto says, "We might recommend pheromone colognes, working out together, or not showering before bed to get your juices running."

Despite her own research on HLA and sexual compatibility, Croy isn't sure how knowing HLA type will help couples. However, some researchers are doing studies on whether HLA types are related to certain cases of infertility, and this is where a genetic test might be very useful, says Croy.

"Otherwise, I think it doesn't matter whether we're HLA compatible or not," she says. "It might give you one possible explanation about why your sexual life isn't as satisfactory as it could be, but there are many other factors that play a role."

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

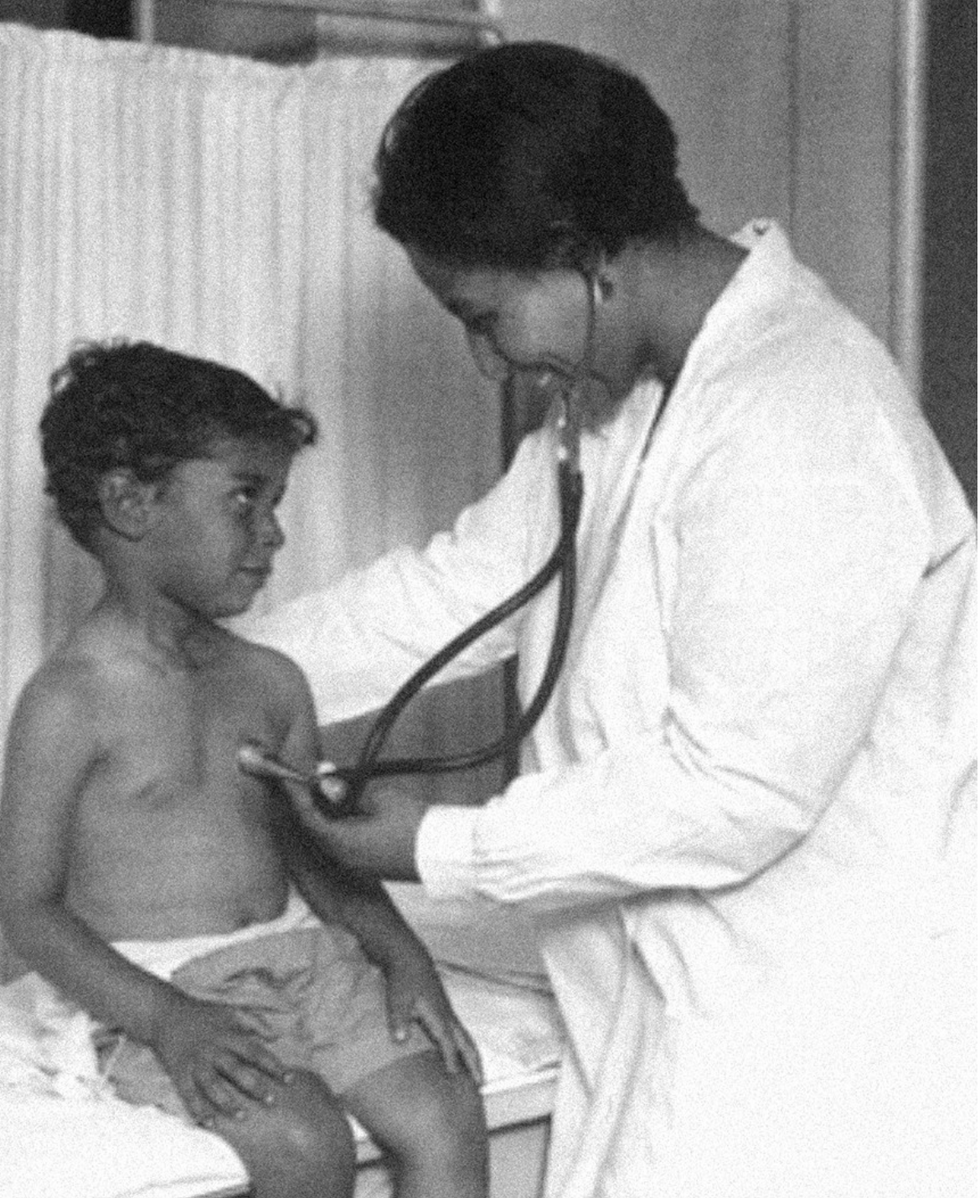

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

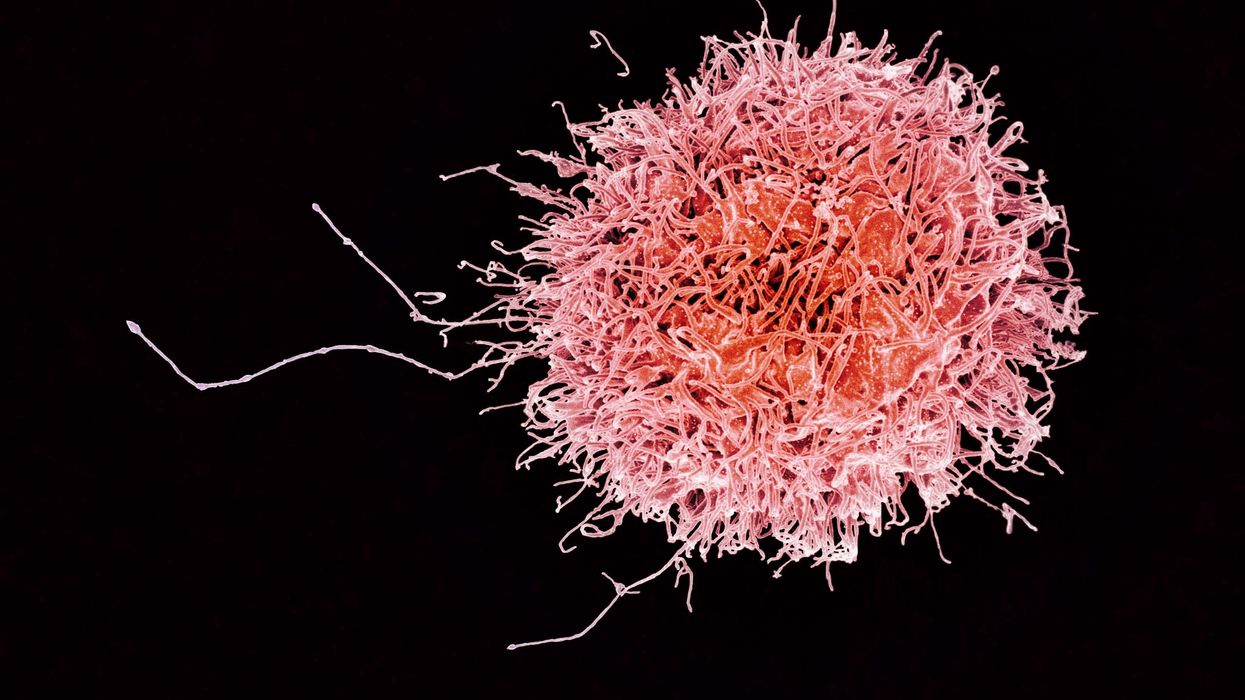

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business