“Synthetic Embryos”: The Wrong Term For Important New Research

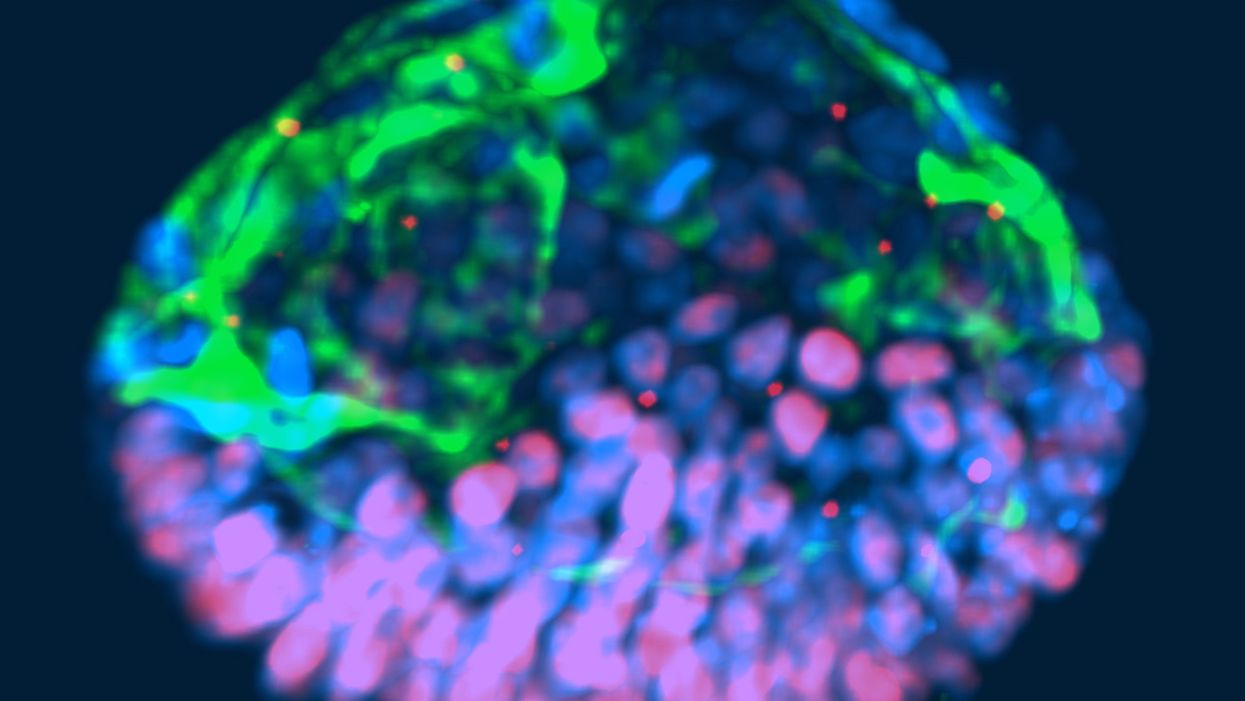

This fluorescent image shows a representative post-implantation amniotic sac embroid.

As a subject of research, an unusual degree of consensus appears to exist among scientists, politicians and the public about human embryos being deserving of special considerations. But what those special considerations should be is less clear. And this is where the subject becomes contentious and opinions diverge because, somewhat surprisingly, what really represents a human embryo has so far not been resolved.

"Prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation."

In 2002, Howard W. Jones Jr., widely considered the "father" of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the U.S., argued in a widely acclaimed article titled "What is an embryo?" that a precondition for the definition of a human embryo was successful implantation. Only once implantation established a biological unit between embryo and mother, could a relatively small number of human cells be considered a human embryo.

Because he felt strongly that human embryos, indeed, deserve special considerations, and should receive those during IVF, he pointed out that, even inside a woman's body, most human embryos (in contrast to other species) never implant and, therefore, are never given a chance at human life. Consequently, he reasoned that prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation.

"One cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is."

This difference, he felt, should also be reflected in scientific language, proposing that embryos prior to implantation in daily IVF practice be called "pre-embryos," with the term "embryo" reserved for post-implantation-stage embryos. Then still unknown to Jones, recent research findings support this viewpoint, since genetic profiles of pre- and post-implantation stage embryos greatly differ.

In an analogy to nature, which in humans allows implantation of only a small minority of naturally generated pre-embryos, IVF centers around the world routinely discard large numbers of pre-embryos, judged inadequate for producing normal pregnancies. Jones' suggestion that only post-implantation embryos should be considered embryos deserving of special considerations, therefore, not only appears prescient and considerate of current IVF practices, but grounded in scientific reality. One, therefore, cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is.

"Much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking."

In 1984, a British ethics committee issued the Warnock Report, which still today prohibits scientists worldwide from studying human embryos in a lab beyond 14 days from fertilization or past formation of the so-called primitive streak, whichever comes first. Well-meaning in its day, its intent was to apply special considerations to human pre-embryos by protecting them from the potential of "feeling pain," once the primitive streak arose on day-15 of development. Formation of the primitive streak signifies a process known as gastrulation, when a subset of cells from the inner cell mass of the pre-embryo are transformed into the three germ layers that comprise all tissues of the developing embryo: The ectoderm, which gives rise to the nervous system; the mesoderm, which gives rise to the circulatory system, muscle, and kidneys; and the endoderm which gives rise to the interior lining of the digestive and respiratory tracts, among other tissues.

That pre-embryos may feel pain at that stage of development was far-fetched in 1984; in view of what we have learned about early human embryology in the 33 years since, it remains untenable today. And, yet, scientists all over the world remain bound by the ethical constraints imposed by the Warnock Report.

A similar ethical paradox exists today for guidelines affecting huge numbers of so-called "abandoned" cryopreserved embryos, often stored ad infinitum in IVF centers all over the world. These are pre-embryos, whose "parents" are no longer responsive to queries from their IVF centers. Current U.S. guidelines allow the disposal of such pre-embryos but prohibit their use in research that may benefit mankind. One, however, wonders whether disposal of huge numbers of abandoned embryos is really more ethical than their use in potentially life-saving human research?

That much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is, indeed, guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking, is also demonstrated by recently expressed concern about so-called "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos. Though both of these terms suggest impending ability to create human embryos from synthetic building blocks, this is not what these terms are meant to describe (such abilities also are not on the horizon). They also do not describe abilities to create gametes (i.e., eggs and sperm) from somatic cells by reprogramming adult peripheral cells, which has already been successfully done in mice by Japanese investigators, leading to the creation of healthy embryos and births and three generations of healthy pubs. Such an approach is at least conceivable as an upcoming infertility treatment.

"A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos."

What all of this noise is really about is the discovery that, as several Rockefeller University investigators recently noted, "Cells have an intrinsic ability to self-assemble and self-organize into complex and functional tissues and organs." Investigators have taken advantage of this ability by creating in the lab so-called "organoids" from accumulations of individual embryonic stem cells. They are defined by three characteristics: (i) they contain a variety of cell types and tissue layers, all typical for a given organ; (ii) these cells are organized similarly to their organization in a specific organ; and (iii) the organoid mimics functions of the organ.

Several other biologists from the Cincinnati Children Hospital Medical Center recently noted that in the last five years, quite a variety of human stem cell-derived organoids, including all three germ layers, have been generated by different research groups around the world, thereby establishing new human model systems that can be used outside the body, in a dish, to investigate otherwise difficult-to-approach organs. Interestingly, they can also be used to investigate early stages of human embryological development.

A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos and, therefore, were given the name "embroids." Though clearly not embryos (the only thing they had in common with human embryos were cell types), they were nevertheless awarded in at least one article the identity of "artificial embryos," which "no one knows how to handle." As Howard Jones so correctly noted, with the word embryo often comes undeserved reverence.

"Any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided; it is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect."

Artificial embryos, therefore, do not exist. Organoids that resemble embryos (i.e., "embroids"), while potentially very useful research objects in studies of early human embryonic cell organization and lineage development, are not embryos--not even pre-embryos. Special considerations for "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos, as recently advocated by some scientists, therefore, appear ethically undeserved. How misdirected and forced some of these efforts are is probably best demonstrated by a recent publication in which a group of Harvard University investigators proposed the term "synthetic human entities with embryo-like features" or SHEEFS" in place of "organoids." Preferably, however, in describing these laboratory-created entities, any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided. It is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect.

Clinical reproductive medicine and reproductive biology, for valid ethical reasons, but also because of myths, misperceptions and, sometimes, outright misrepresentations of facts for political reasons, are under more public scrutiny than most other science areas. Yet, at least in the realm of biomedical research, nothing appears more important than better understanding the first few days of human embryo development. A recent study involving genetic editing of human embryos, reported by British investigators in Nature, once again confirmed what biologist have known for some time: No animal model faithfully recapitulates most of human developmental origins. The most important secrets nature still has to tell us, will not be revealed through mouse or other animal studies. We will discover them only through the study of early-stage human embryos – and we, therefore, should not limit the use of lab-grown organoids to help further that research.

Understanding early human development "will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine."

As Howard Jones intuitively noticed, words matter. Appropriate and uniformly accepted definitions and terms are not only essential for scientific communications but, within the context of human reproduction, often elicit strong emotional reactions, and are easily misappropriated by those opposed to most interventions into human reproduction.

Who does not recall the early days of IVF in the late 1970s, when even reputable news outlets raised the specter of Frankenstein monsters created through the IVF process? Millions of IVF births later, a Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology was in 2010 finally awarded to the biologist Robert Edwards who, together with the gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, reported the first live birth through IVF on July 25, 1978. Many more awards are still waiting for recipients who through the study of early human embryo development will discover how cell fate is determined and cells acquire highly specific functions; how rapid cell proliferation takes place and, when required, stops; why chromosomal abnormalities are so common in early stage embryos and what their function may be.

Those who will discover these and many other important answers, will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine. Learning how to control cell proliferation, for example, will likely revolutionize cancer therapy; I started my research career in biology with a study published in 1980 of "common denominators of pregnancy and malignancy." If regulatory prohibitions are not allowed to interfere in rapidly progressing research opportunities involving organoids and pre-embryos, we will, finally, see the circle closing, with the most rewarding benefits for mankind ever achieved through biological research.

Editor's Note: Read a different viewpoint here written by one of the world's top experts on the ethics of stem cell research.

This man spent over 70 years in an iron lung. What he was able to accomplish is amazing.

Paul Alexander spent more than 70 years confined to an iron lung after a polio infection left him paralyzed at age 6. Here, Alexander uses a mirror attached to the top of his iron lung to view his surroundings.

It’s a sight we don’t normally see these days: A man lying prone in a big, metal tube with his head sticking out of one end. But it wasn’t so long ago that this sight was unfortunately much more common.

In the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of people each year were infected by polio—a highly contagious virus that attacks nerves in the spinal cord and brainstem. Many people survived polio, but a small percentage of people who did were left permanently paralyzed from the virus, requiring support to help them breathe. This support, known as an “iron lung,” manually pulled oxygen in and out of a person’s lungs by changing the pressure inside the machine.

Paul Alexander was one of several thousand who were infected and paralyzed by polio in 1952. That year, a polio epidemic swept the United States, forcing businesses to close and polio wards in hospitals all over the country to fill up with sick children. When Paul caught polio in the summer of 1952, doctors urged his parents to let him rest and recover at home, since the hospital in his home suburb of Dallas, Texas was already overrun with polio patients.

Paul rested in bed for a few days with aching limbs and a fever. But his condition quickly got worse. Within a week, Paul could no longer speak or swallow, and his parents rushed him to the local hospital where the doctors performed an emergency procedure to help him breathe. Paul woke from the surgery three days later, and found himself unable to move and lying inside an iron lung in the polio ward, surrounded by rows of other paralyzed children.

But against all odds, Paul lived. And with help from a physical therapist, Paul was able to thrive—sometimes for small periods outside the iron lung.

The way Paul did this was to practice glossopharyngeal breathing (or as Paul called it, “frog breathing”), where he would trap air in his mouth and force it down his throat and into his lungs by flattening his tongue. This breathing technique, taught to him by his physical therapist, would allow Paul to leave the iron lung for increasing periods of time.

With help from his iron lung (and for small periods of time without it), Paul managed to live a full, happy, and sometimes record-breaking life. At 21, Paul became the first person in Dallas, Texas to graduate high school without attending class in person, owing his success to memorization rather than taking notes. After high school, Paul received a scholarship to Southern Methodist University and pursued his dream of becoming a trial lawyer and successfully represented clients in court.

Throughout his long life, Paul was also able to fly on a plane, visit the beach, adopt a dog, fall in love, and write a memoir using a plastic stick to tap out a draft on a keyboard. In recent years, Paul joined TikTok and became a viral sensation with more than 330,000 followers. In one of his first videos, Paul advocated for vaccination and warned against another polio epidemic.

Paul was reportedly hospitalized with COVID-19 at the end of February and died on March 11th, 2024. He currently holds the Guiness World Record for longest survival inside an iron lung—71 years.

Polio thankfully no longer circulates in the United States, or in most of the world, thanks to vaccines. But Paul continues to serve as a reminder of the importance of vaccination—and the power of the human spirit.

““I’ve got some big dreams. I’m not going to accept from anybody their limitations,” he said in a 2022 interview with CNN. “My life is incredible.”

When doctors couldn’t stop her daughter’s seizures, this mom earned a PhD and found a treatment herself.

Savannah Salazar (left) and her mother, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar, who earned a PhD in neurobiology in the quest for a treatment of her daughter's seizure disorder.

Twenty-eight years ago, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar woke to the sound of her daughter, two-year-old Savannah, in the midst of a medical emergency.

“I entered [Savannah’s room] to see her tiny little body jerking about violently in her bed,” Tracy said in an interview. “I thought she was choking.” When she and her husband frantically called 911, the paramedic told them it was likely that Savannah had had a seizure—a term neither Tracy nor her husband had ever heard before.

Over the next several years, Savannah’s seizures continued and worsened. By age five Savannah was having seizures dozens of times each day, and her parents noticed significant developmental delays. Savannah was unable to use the restroom and functioned more like a toddler than a five-year-old.

Doctors were mystified: Tracy and her husband had no family history of seizures, and there was no event—such as an injury or infection—that could have caused them. Doctors were also confused as to why Savannah’s seizures were happening so frequently despite trying different seizure medications.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Savannah with Lennox-Gaustaut Syndrome, or LGS, an epilepsy disorder with no cure and a poor prognosis. People with LGS are often resistant to several kinds of anti-seizure medications, and often suffer from developmental delays and behavioral problems. People with LGS also have a higher chance of injury as well as a higher chance of sudden unexpected death (SUDEP) due to the frequent seizures. In about 70 percent of cases, LGS has an identifiable cause such as a brain injury or genetic syndrome. In about 30 percent of cases, however, the cause is unknown.

Watching her daughter struggle through repeated seizures was devastating to Tracy and the rest of the family.

“This disease, it comes into your life. It’s uninvited. It’s unannounced and it takes over every aspect of your daily life,” said Tracy in an interview with Today.com. “Plus it’s attacking the thing that is most precious to you—your kid.”

Desperate to find some answers, Tracy began combing the medical literature for information about epilepsy and LGS. She enrolled in college courses to better understand the papers she was reading.

“Ironically, I thought I needed to go to college to take English classes to understand these papers—but soon learned it wasn’t English classes I needed, It was science,” Tracy said. When she took her first college science course, Tracy says, she “fell in love with the subject.”

Tracy was now a caregiver to Savannah, who continued to have hundreds of seizures a month, as well as a full-time student, studying late into the night and while her kids were at school, using classwork as “an outlet for the pain.”

“I couldn’t help my daughter,” Tracy said. “Studying was something I could do.”

Twelve years later, Tracy had earned a PhD in neurobiology.

After her post-doctoral training, Tracy started working at a lab that explored the genetics of epilepsy. Savannah’s doctors hadn’t found a genetic cause for her seizures, so Tracy decided to sequence her genome again to check for other abnormalities—and what she found was life-changing.

Tracy discovered that Savannah had a calcium channel mutation, meaning that too much calcium was passing through Savannah’s neural pathways, leading to seizures. The information made sense to Tracy: Anti-seizure medications often leech calcium from a person’s bones. When doctors had prescribed Savannah calcium supplements in the past to counteract these effects, her seizures had gotten worse every time she took the medication. Tracy took her discovery to Savannah’s doctor, who agreed to prescribe her a calcium blocker.

The change in Savannah was almost immediate.

Within two weeks, Savannah’s seizures had decreased by 95 percent. Once on a daily seven-drug regimen, she was soon weaned to just four, and then three. Amazingly, Tracy started to notice changes in Savannah’s personality and development, too.

“She just exploded in her personality and her talking and her walking and her potty training and oh my gosh she is just so sassy,” Tracy said in an interview.

Since starting the calcium blocker eleven years ago, Savannah has continued to make enormous strides. Though still unable to read or write, Savannah enjoys puzzles and social media. She’s “obsessed” with boys, says Tracy. And while Tracy suspects she’ll never be able to live independently, she and her daughter can now share more “normal” moments—something she never anticipated at the start of Savannah’s journey with LGS. While preparing for an event, Savannah helped Tracy get ready.

“We picked out a dress and it was the first time in our lives that we did something normal as a mother and a daughter,” she said. “It was pretty cool.”