“Synthetic Embryos”: The Wrong Term For Important New Research

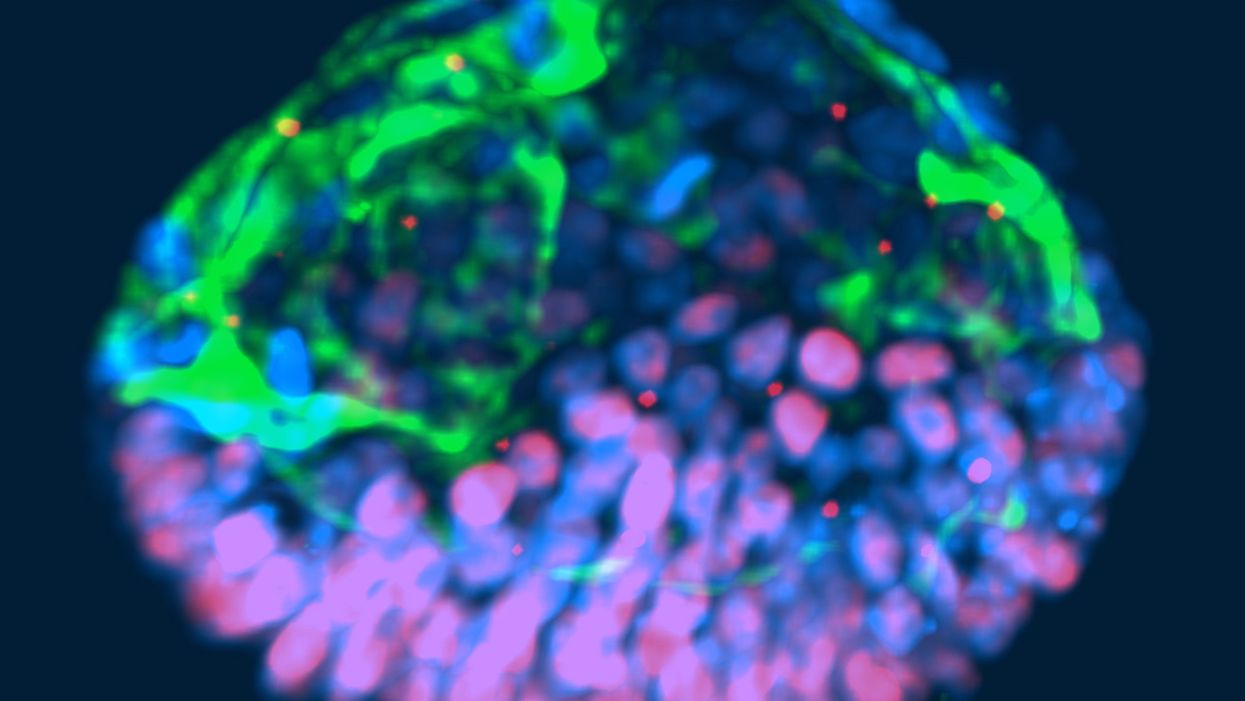

This fluorescent image shows a representative post-implantation amniotic sac embroid.

As a subject of research, an unusual degree of consensus appears to exist among scientists, politicians and the public about human embryos being deserving of special considerations. But what those special considerations should be is less clear. And this is where the subject becomes contentious and opinions diverge because, somewhat surprisingly, what really represents a human embryo has so far not been resolved.

"Prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation."

In 2002, Howard W. Jones Jr., widely considered the "father" of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the U.S., argued in a widely acclaimed article titled "What is an embryo?" that a precondition for the definition of a human embryo was successful implantation. Only once implantation established a biological unit between embryo and mother, could a relatively small number of human cells be considered a human embryo.

Because he felt strongly that human embryos, indeed, deserve special considerations, and should receive those during IVF, he pointed out that, even inside a woman's body, most human embryos (in contrast to other species) never implant and, therefore, are never given a chance at human life. Consequently, he reasoned that prior to implantation, embryos must be given a different level of reverence than after implantation.

"One cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is."

This difference, he felt, should also be reflected in scientific language, proposing that embryos prior to implantation in daily IVF practice be called "pre-embryos," with the term "embryo" reserved for post-implantation-stage embryos. Then still unknown to Jones, recent research findings support this viewpoint, since genetic profiles of pre- and post-implantation stage embryos greatly differ.

In an analogy to nature, which in humans allows implantation of only a small minority of naturally generated pre-embryos, IVF centers around the world routinely discard large numbers of pre-embryos, judged inadequate for producing normal pregnancies. Jones' suggestion that only post-implantation embryos should be considered embryos deserving of special considerations, therefore, not only appears prescient and considerate of current IVF practices, but grounded in scientific reality. One, therefore, cannot help but wonder about the fog of misconceptions and misrepresentations that still surrounds what an embryo is.

"Much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking."

In 1984, a British ethics committee issued the Warnock Report, which still today prohibits scientists worldwide from studying human embryos in a lab beyond 14 days from fertilization or past formation of the so-called primitive streak, whichever comes first. Well-meaning in its day, its intent was to apply special considerations to human pre-embryos by protecting them from the potential of "feeling pain," once the primitive streak arose on day-15 of development. Formation of the primitive streak signifies a process known as gastrulation, when a subset of cells from the inner cell mass of the pre-embryo are transformed into the three germ layers that comprise all tissues of the developing embryo: The ectoderm, which gives rise to the nervous system; the mesoderm, which gives rise to the circulatory system, muscle, and kidneys; and the endoderm which gives rise to the interior lining of the digestive and respiratory tracts, among other tissues.

That pre-embryos may feel pain at that stage of development was far-fetched in 1984; in view of what we have learned about early human embryology in the 33 years since, it remains untenable today. And, yet, scientists all over the world remain bound by the ethical constraints imposed by the Warnock Report.

A similar ethical paradox exists today for guidelines affecting huge numbers of so-called "abandoned" cryopreserved embryos, often stored ad infinitum in IVF centers all over the world. These are pre-embryos, whose "parents" are no longer responsive to queries from their IVF centers. Current U.S. guidelines allow the disposal of such pre-embryos but prohibit their use in research that may benefit mankind. One, however, wonders whether disposal of huge numbers of abandoned embryos is really more ethical than their use in potentially life-saving human research?

That much of the regulatory environment surrounding research on human embryos is, indeed, guided by emotions rather than science and logical thinking, is also demonstrated by recently expressed concern about so-called "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos. Though both of these terms suggest impending ability to create human embryos from synthetic building blocks, this is not what these terms are meant to describe (such abilities also are not on the horizon). They also do not describe abilities to create gametes (i.e., eggs and sperm) from somatic cells by reprogramming adult peripheral cells, which has already been successfully done in mice by Japanese investigators, leading to the creation of healthy embryos and births and three generations of healthy pubs. Such an approach is at least conceivable as an upcoming infertility treatment.

"A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos."

What all of this noise is really about is the discovery that, as several Rockefeller University investigators recently noted, "Cells have an intrinsic ability to self-assemble and self-organize into complex and functional tissues and organs." Investigators have taken advantage of this ability by creating in the lab so-called "organoids" from accumulations of individual embryonic stem cells. They are defined by three characteristics: (i) they contain a variety of cell types and tissue layers, all typical for a given organ; (ii) these cells are organized similarly to their organization in a specific organ; and (iii) the organoid mimics functions of the organ.

Several other biologists from the Cincinnati Children Hospital Medical Center recently noted that in the last five years, quite a variety of human stem cell-derived organoids, including all three germ layers, have been generated by different research groups around the world, thereby establishing new human model systems that can be used outside the body, in a dish, to investigate otherwise difficult-to-approach organs. Interestingly, they can also be used to investigate early stages of human embryological development.

A team of biologists and engineers at the University of Michigan recently received media attention after creating organoids from embryonic stem cells that resembled human embryos and, therefore, were given the name "embroids." Though clearly not embryos (the only thing they had in common with human embryos were cell types), they were nevertheless awarded in at least one article the identity of "artificial embryos," which "no one knows how to handle." As Howard Jones so correctly noted, with the word embryo often comes undeserved reverence.

"Any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided; it is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect."

Artificial embryos, therefore, do not exist. Organoids that resemble embryos (i.e., "embroids"), while potentially very useful research objects in studies of early human embryonic cell organization and lineage development, are not embryos--not even pre-embryos. Special considerations for "artificial" or "synthetic" embryos, as recently advocated by some scientists, therefore, appear ethically undeserved. How misdirected and forced some of these efforts are is probably best demonstrated by a recent publication in which a group of Harvard University investigators proposed the term "synthetic human entities with embryo-like features" or SHEEFS" in place of "organoids." Preferably, however, in describing these laboratory-created entities, any association with the term "embryo" should be avoided. It is not only misleading and irresponsible but scientifically incorrect.

Clinical reproductive medicine and reproductive biology, for valid ethical reasons, but also because of myths, misperceptions and, sometimes, outright misrepresentations of facts for political reasons, are under more public scrutiny than most other science areas. Yet, at least in the realm of biomedical research, nothing appears more important than better understanding the first few days of human embryo development. A recent study involving genetic editing of human embryos, reported by British investigators in Nature, once again confirmed what biologist have known for some time: No animal model faithfully recapitulates most of human developmental origins. The most important secrets nature still has to tell us, will not be revealed through mouse or other animal studies. We will discover them only through the study of early-stage human embryos – and we, therefore, should not limit the use of lab-grown organoids to help further that research.

Understanding early human development "will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine."

As Howard Jones intuitively noticed, words matter. Appropriate and uniformly accepted definitions and terms are not only essential for scientific communications but, within the context of human reproduction, often elicit strong emotional reactions, and are easily misappropriated by those opposed to most interventions into human reproduction.

Who does not recall the early days of IVF in the late 1970s, when even reputable news outlets raised the specter of Frankenstein monsters created through the IVF process? Millions of IVF births later, a Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology was in 2010 finally awarded to the biologist Robert Edwards who, together with the gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, reported the first live birth through IVF on July 25, 1978. Many more awards are still waiting for recipients who through the study of early human embryo development will discover how cell fate is determined and cells acquire highly specific functions; how rapid cell proliferation takes place and, when required, stops; why chromosomal abnormalities are so common in early stage embryos and what their function may be.

Those who will discover these and many other important answers, will not only greatly enhance the biological understanding of our species; but also will open groundbreaking new therapeutic options in all areas of medicine. Learning how to control cell proliferation, for example, will likely revolutionize cancer therapy; I started my research career in biology with a study published in 1980 of "common denominators of pregnancy and malignancy." If regulatory prohibitions are not allowed to interfere in rapidly progressing research opportunities involving organoids and pre-embryos, we will, finally, see the circle closing, with the most rewarding benefits for mankind ever achieved through biological research.

Editor's Note: Read a different viewpoint here written by one of the world's top experts on the ethics of stem cell research.

A robot server, controlled remotely by a disabled worker, delivers drinks to patrons at the DAWN cafe in Tokyo.

A sleek, four-foot tall white robot glides across a cafe storefront in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district, holding a two-tiered serving tray full of tea sandwiches and pastries. The cafe’s patrons smile and say thanks as they take the tray—but it’s not the robot they’re thanking. Instead, the patrons are talking to the person controlling the robot—a restaurant employee who operates the avatar from the comfort of their home.

It’s a typical scene at DAWN, short for Diverse Avatar Working Network—a cafe that launched in Tokyo six years ago as an experimental pop-up and quickly became an overnight success. Today, the cafe is a permanent fixture in Nihonbashi, staffing roughly 60 remote workers who control the robots remotely and communicate to customers via a built-in microphone.

More than just a creative idea, however, DAWN is being hailed as a life-changing opportunity. The workers who control the robots remotely (known as “pilots”) all have disabilities that limit their ability to move around freely and travel outside their homes. Worldwide, an estimated 16 percent of the global population lives with a significant disability—and according to the World Health Organization, these disabilities give rise to other problems, such as exclusion from education, unemployment, and poverty.

These are all problems that Kentaro Yoshifuji, founder and CEO of Ory Laboratory, which supplies the robot servers at DAWN, is looking to correct. Yoshifuji, who was bedridden for several years in high school due to an undisclosed health problem, launched the company to help enable people who are house-bound or bedridden to more fully participate in society, as well as end the loneliness, isolation, and feelings of worthlessness that can sometimes go hand-in-hand with being disabled.

“It’s heartbreaking to think that [people with disabilities] feel they are a burden to society, or that they fear their families suffer by caring for them,” said Yoshifuji in an interview in 2020. “We are dedicating ourselves to providing workable, technology-based solutions. That is our purpose.”

Shota, Kuwahara, a DAWN employee with muscular dystrophy, agrees. "There are many difficulties in my daily life, but I believe my life has a purpose and is not being wasted," he says. "Being useful, able to help other people, even feeling needed by others, is so motivational."

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.