The Case for an Outright Ban on Facial Recognition Technology

Some experts worry that facial recognition technology is a dangerous enough threat to our basic rights that it should be entirely banned from police and government use.

[Editor's Note: This essay is in response to our current Big Question, which we posed to experts with different perspectives: "Do you think the use of facial recognition technology by the police or government should be banned? If so, why? If not, what limits, if any, should be placed on its use?"]

In a surprise appearance at the tail end of Amazon's much-hyped annual product event last month, CEO Jeff Bezos casually told reporters that his company is writing its own facial recognition legislation.

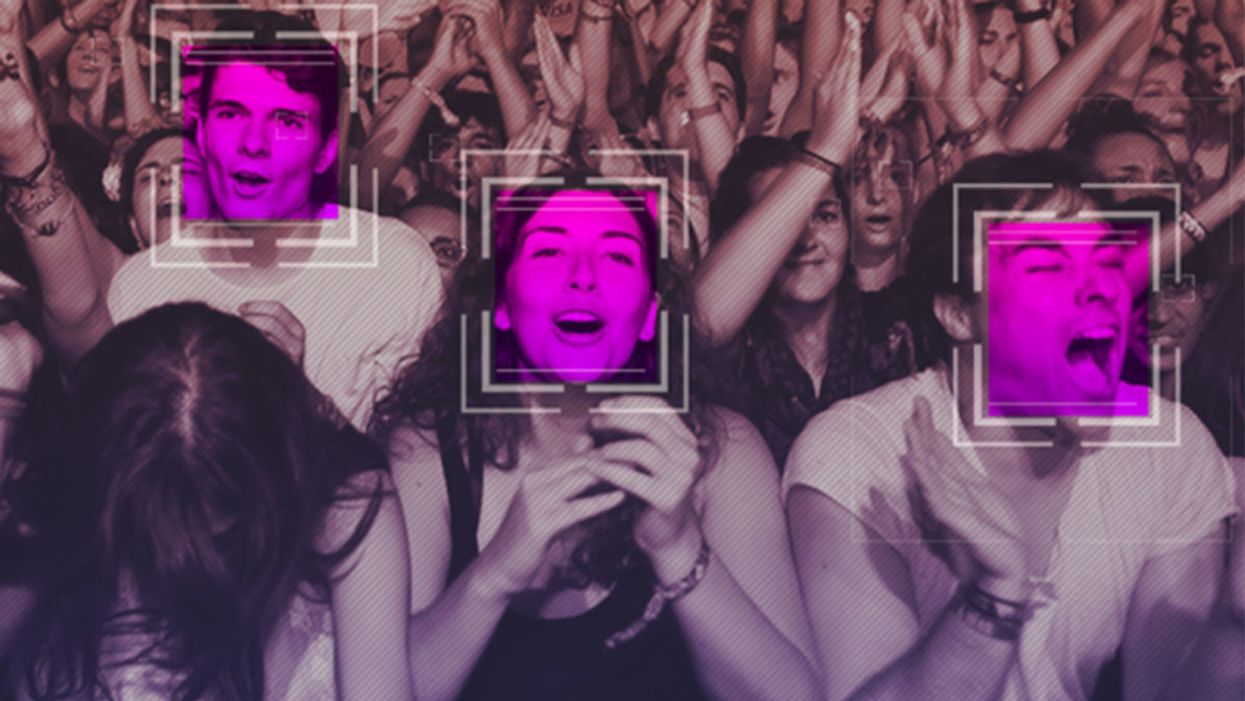

The use of computer algorithms to analyze massive databases of footage and photographs could render human privacy extinct.

It seems that when you're the wealthiest human alive, there's nothing strange about your company––the largest in the world profiting from the spread of face surveillance technology––writing the rules that govern it.

But if lawmakers and advocates fall into Silicon Valley's trap of "regulating" facial recognition and other forms of invasive biometric surveillance, that's exactly what will happen.

Industry-friendly regulations won't fix the dangers inherent in widespread use of face scanning software, whether it's deployed by governments or for commercial purposes. The use of this technology in public places and for surveillance purposes should be banned outright, and its use by private companies and individuals should be severely restricted. As artificial intelligence expert Luke Stark wrote, it's dangerous enough that it should be outlawed for "almost all practical purposes."

Like biological or nuclear weapons, facial recognition poses such a profound threat to the future of humanity and our basic rights that any potential benefits are far outweighed by the inevitable harms.

We live in cities and towns with an exponentially growing number of always-on cameras, installed in everything from cars to children's toys to Amazon's police-friendly doorbells. The use of computer algorithms to analyze massive databases of footage and photographs could render human privacy extinct. It's a world where nearly everything we do, everywhere we go, everyone we associate with, and everything we buy — or look at and even think of buying — is recorded and can be tracked and analyzed at a mass scale for unimaginably awful purposes.

Biometric tracking enables the automated and pervasive monitoring of an entire population. There's ample evidence that this type of dragnet mass data collection and analysis is not useful for public safety, but it's perfect for oppression and social control.

Law enforcement defenders of facial recognition often state that the technology simply lets them do what they would be doing anyway: compare footage or photos against mug shots, drivers licenses, or other databases, but faster. And they're not wrong. But the speed and automation enabled by artificial intelligence-powered surveillance fundamentally changes the impact of that surveillance on our society. Being able to do something exponentially faster, and using significantly less human and financial resources, alters the nature of that thing. The Fourth Amendment becomes meaningless in a world where private companies record everything we do and provide governments with easy tools to request and analyze footage from a growing, privately owned, panopticon.

Tech giants like Microsoft and Amazon insist that facial recognition will be a lucrative boon for humanity, as long as there are proper safeguards in place. This disingenuous call for regulation is straight out of the same lobbying playbook that telecom companies have used to attack net neutrality and Silicon Valley has used to scuttle meaningful data privacy legislation. Companies are calling for regulation because they want their corporate lawyers and lobbyists to help write the rules of the road, to ensure those rules are friendly to their business models. They're trying to skip the debate about what role, if any, technology this uniquely dangerous should play in a free and open society. They want to rush ahead to the discussion about how we roll it out.

We need spaces that are free from government and societal intrusion in order to advance as a civilization.

Facial recognition is spreading very quickly. But backlash is growing too. Several cities have already banned government entities, including police and schools, from using biometric surveillance. Others have local ordinances in the works, and there's state legislation brewing in Michigan, Massachusetts, Utah, and California. Meanwhile, there is growing bipartisan agreement in U.S. Congress to rein in government use of facial recognition. We've also seen significant backlash to facial recognition growing in the U.K., within the European Parliament, and in Sweden, which recently banned its use in schools following a fine under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

At least two frontrunners in the 2020 presidential campaign have backed a ban on law enforcement use of facial recognition. Many of the largest music festivals in the world responded to Fight for the Future's campaign and committed to not use facial recognition technology on music fans.

There has been widespread reporting on the fact that existing facial recognition algorithms exhibit systemic racial and gender bias, and are more likely to misidentify people with darker skin, or who are not perceived by a computer to be a white man. Critics are right to highlight this algorithmic bias. Facial recognition is being used by law enforcement in cities like Detroit right now, and the racial bias baked into that software is doing harm. It's exacerbating existing forms of racial profiling and discrimination in everything from public housing to the criminal justice system.

But the companies that make facial recognition assure us this bias is a bug, not a feature, and that they can fix it. And they might be right. Face scanning algorithms for many purposes will improve over time. But facial recognition becoming more accurate doesn't make it less of a threat to human rights. This technology is dangerous when it's broken, but at a mass scale, it's even more dangerous when it works. And it will still disproportionately harm our society's most vulnerable members.

Persistent monitoring and policing of our behavior breeds conformity, benefits tyrants, and enriches elites.

We need spaces that are free from government and societal intrusion in order to advance as a civilization. If technology makes it so that laws can be enforced 100 percent of the time, there is no room to test whether those laws are just. If the U.S. government had ubiquitous facial recognition surveillance 50 years ago when homosexuality was still criminalized, would the LGBTQ rights movement ever have formed? In a world where private spaces don't exist, would people have felt safe enough to leave the closet and gather, build community, and form a movement? Freedom from surveillance is necessary for deviation from social norms as well as to dissent from authority, without which societal progress halts.

Persistent monitoring and policing of our behavior breeds conformity, benefits tyrants, and enriches elites. Drawing a line in the sand around tech-enhanced surveillance is the fundamental fight of this generation. Lining up to get our faces scanned to participate in society doesn't just threaten our privacy, it threatens our humanity, and our ability to be ourselves.

[Editor's Note: Read the opposite perspective here.]

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.