Top Fertility Doctor: Artificially Created Sperm and Eggs "Will Become Normal" One Day

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A rendering of in vitro fertilization.

Imagine two men making a baby. Or two women. Or an infertile couple. Or an older woman whose eggs are no longer viable. None of these people could have a baby today without the help of an egg or sperm donor.

Cells scraped from the inside of your cheek could one day be manipulated to become either eggs or sperm.

But in the future, it may be possible for them to reproduce using only their own genetic material, thanks to an emerging technology called IVG, or in vitro gametogenesis.

Researchers are learning how to reprogram adult human cells like skin cells to become lab-created egg and sperm cells, which could then be joined to form an embryo. In other words, cells scraped from the inside of your cheek could one day be manipulated to become either eggs or sperm, no matter your gender or your reproductive fitness.

In 2016, Japanese scientists proved that the concept could be successfully carried out in mice. Now some experts, like Dr. John Zhang, the founder and CEO of New Hope Fertility Center in Manhattan, say it's just "a matter of time" before the method is also made to work in humans.

Such a technological tour de force would upend our most basic assumptions about human reproduction and biology. Combined with techniques like gene editing, these tools could eventually enable prospective parents to have an unprecedented level of choice and control over their children's origins. It's a wildly controversial notion, and an especially timely one now that a Chinese scientist has announced the birth of the first allegedly CRISPR-edited babies. (The claims remain unverified.)

Zhang himself is no stranger to controversy. In 2016, he stunned the world when he announced the birth of a baby conceived using the DNA of three people, a landmark procedure intended to prevent the baby from inheriting a devastating neurological disease. (Zhang went to a clinic in Mexico to carry out the procedure because it is prohibited in the U.S.) Zhang's other achievements to date include helping a 49-year-old woman have a baby using her own eggs and restoring a young woman's fertility through an ovarian tissue transplant surgery.

Zhang recently sat down with our Editor-in-Chief in his New York office overlooking Columbus Circle to discuss the fertility world's latest provocative developments. Here are his top ten insights:

Clearly [gene-editing embryos] will be beneficial to mankind, but it's a matter of how and when the work is done.

1) On a Chinese scientist's claim of creating the first CRISPR-edited babies:

I'm glad that we made a first move toward a clinical application of this technology for mankind. Somebody has to do this. Whether this was a good case or not, there is still time to find out.

Clearly it will be beneficial to mankind, but it's a matter of how and when the work is done. Like any scientific advance, it has to be done in a very responsible way.

Today's response is identical to when the world's first IVF baby was announced in 1978. The major news media didn't take it seriously and thought it was evil, wanted to keep a distance from IVF. Many countries even abandoned IVF, but today you see it is a normal practice. And it took almost 40 years [for the researchers] to win a Nobel Prize.

I think we need more time to understand how this work was done medically, ethically, and let the scientist have the opportunity to present how it was done and let a scientific journal publish the paper. Before these become available, I don't think we should start being upset, scared, or giving harsh criticism.

2) On the international outcry in response to the news:

I feel we are in scientific shock, with many thinking it came too fast, too soon. We all embrace modern technology, but when something really comes along, we fear it. In an old Chinese saying, one of the masters always dreamed of seeing the dragon, and when the dragon really came, he got scared.

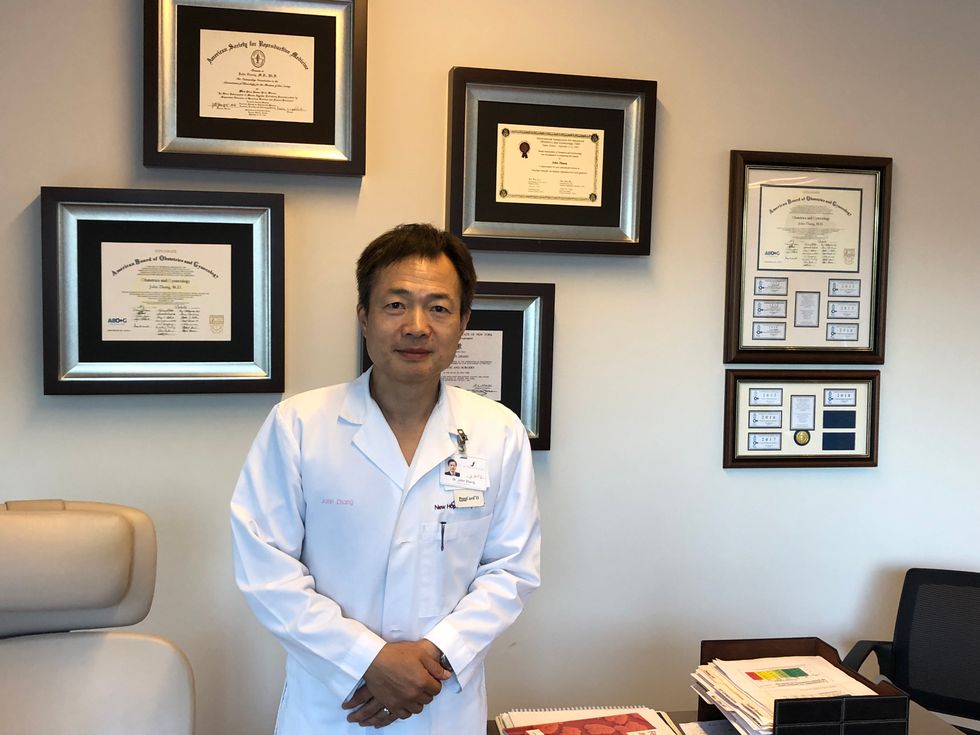

Dr. John Zhang, the founder and CEO of New Hope Fertility Center in Manhattan, pictured in his office.

3) On the Western world's perception that Chinese scientists sometimes appear to discount ethics in favor of speedy breakthroughs:

I think this perception is not fair. I don't think China is very casual. It's absolutely not what people think. I don't want people to feel that this case [of CRISPR-edited babies] will mean China has less standards over how human reproduction should be performed. Just because this happened, it doesn't mean in China you can do anything you want.

As far as the regulation of IVF clinics, China is probably the most strictly regulated of any country I know in this world.

4) On China's first public opinion poll gauging attitudes toward gene-edited babies, indicating that more than 60 percent of survey respondents supported using the technology to prevent inherited diseases, but not to enhance traits:

There is a sharp contrast between the general public and the professional world. Being a working health professional and an advocate of scientists working in this field, it is very important to be ethically responsible for what we are doing, but my own feeling is that from time to time we may not take into consideration what the patient needs.

5) On how the three-parent baby is doing today, several years after his birth:

No news is good news.

6) On the potentially game-changing research to develop artificial sperm and eggs:

First of all I think that anything that's technically possible, as long as you are not harmful to other people, to other societies, as long as you do it responsibly, and this is a legitimate desire, I think eventually it will become reality.

My research for now is really to try to overcome the very next obstacle in our field, which is how to let a lady age 44 or older have a baby with her own genetic material.

Practically 99 percent of women over age 43 will never make a baby on their own. And after age 47, we usually don't offer donor egg IVF anymore.

But with improved longevity, and quality of life, the lifespan of females continues to increase. In Japan, the average for females is about 89 years old. So for more than half of your life, you will not be able to produce a baby, which is quite significant in the animal kingdom. In most of the animal kingdom, their reproductive life is very much the same as their life, but then you can argue in the animal kingdom unlike a human being, it doesn't take such a long time for them to contribute to the society because once you know how to hunt and look for food, you're done.

"I think this will become a major ethical debate: whether we should let an older lady have a baby at a very late state of her life."

But humans are different. You need to go to college, get certain skills. It takes 20 years to really bring a human being up to become useful to society. That's why the mom and dad are not supposed to have the same reproductive life equal to their real life.

I think this will become a major ethical debate: whether we should let an older lady have a baby at a very late state of her life and leave the future generation in a very vulnerable situation in which they may lack warm caring, proper guidance, and proper education.

7) On using artificial gametes to grant more reproductive choices to gays and lesbians:

I think it is totally possible to have two sperm make a baby, and two eggs make babies.

If we have two guys, one guy to produce eggs, or two girls, one would have to become sperm. Basically you are creating artificial gametes or converting with gametes from sperm to become egg or egg to become a sperm. Which may not necessarily be very difficult. The key is to be able to do nuclear reprogramming.

So why can two sperm not make offspring now? You get exactly half of your genes from each parent. The genes have their own imprinting that say "made in mom," "made in dad." The two sperm would say "made in dad," "made in dad." If I can erase the "made in dad," and say "made in mom," then these sperm can make offspring.

8) On how close science is to creating artificial gametes for clinical use in pregnancies:

It's very hard to say until we accomplish it. It could be very quick. It could be it takes a long time. I don't want to speculate.

"I think these technologies are the solid foundation just like when we designed the computer -- we never thought a computer would become the iPhone."

9) On whether there should be ethical red lines drawn by authorities or whether the decisions should be left to patients and scientists:

I think we cannot believe a hundred percent in the scientist and the patient but it should not be 100 percent authority. It should be coming from the whole of society.

10) On his expectations for the future:

We are living in a very exciting world. I think that all these technologies can really change the way of mankind and also are not just for baby-making. The research, the experience, the mechanism we learn from these technologies, they will shine some great lights into our long-held dream of being a healthy population that is cancer-free and lives a long life, let's say 120 years.

I think these technologies are the solid foundation just like when we designed the computer -- we never thought a computer would become the iPhone. Imagine making a computer 30 years ago, that this little chip will change your life.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Some hospitals are pioneers in ditching plastic, turning green

In the U.S., hospitals generate an estimated 6,000 tons of waste per day. A few clinics are leading the way in transitioning to clean energy sources.

This is part 2 of a three part series on a new generation of doctors leading the charge to make the health care industry more sustainable - for the benefit of their patients and the planet. Read part 1 here and part 3 here.

After graduating from her studies as an engineer, Nora Stroetzel ticked off the top item on her bucket list and traveled the world for a year. She loved remote places like the Indonesian rain forest she reached only by hiking for several days on foot, mountain villages in the Himalayas, and diving at reefs that were only accessible by local fishing boats.

“But no matter how far from civilization I ventured, one thing was already there: plastic,” Stroetzel says. “Plastic that would stay there for centuries, on 12,000 foot peaks and on beaches several hundred miles from the nearest city.” She saw “wild orangutans that could be lured by rustling plastic and hermit crabs that used plastic lids as dwellings instead of shells.”

While traveling she started volunteering for beach cleanups and helped build a recycling station in Indonesia. But the pivotal moment for her came after she returned to her hometown Kiel in Germany. “At the dentist, they gave me a plastic cup to rinse my mouth. I used it for maybe ten seconds before it was tossed out,” Stroetzel says. “That made me really angry.”

She decided to research alternatives for plastic in the medical sector and learned that cups could be reused and easily disinfected. All dentists routinely disinfect their tools anyway and, Stroetzel reasoned, it wouldn’t be too hard to extend that practice to cups.

It's a good example for how often plastic is used unnecessarily in medical practice, she says. The health care sector is the fifth biggest source of pollution and trash in industrialized countries. In the U.S., hospitals generate an estimated 6,000 tons of waste per day, including an average of 400 grams of plastic per patient per day, and this sector produces 8.5 percent of greenhouse gas emissions nationwide.

“Sustainable alternatives exist,” Stroetzel says, “but you have to painstakingly look for them; they are often not offered by the big manufacturers, and all of this takes way too much time [that] medical staff simply does not have during their hectic days.”

When Stroetzel spoke with medical staff in Germany, she found they were often frustrated by all of this waste, especially as they took care to avoid single-use plastic at home. Doctors in other countries share this frustration. In a recent poll, nine out of ten doctors in Germany said they’re aware of the urgency to find sustainable solutions in the health industry but don’t know how to achieve this goal.

After a year of researching more sustainable alternatives, Stroetzel founded a social enterprise startup called POP, short for Practice Without Plastic, together with IT expert Nicolai Niethe, to offer well-researched solutions. “Sustainable alternatives exist,” she says, “but you have to painstakingly look for them; they are often not offered by the big manufacturers, and all of this takes way too much time [that] medical staff simply does not have during their hectic days.”

In addition to reusable dentist cups, other good options for the heath care sector include washable N95 face masks and gloves made from nitrile, which waste less water and energy in their production. But Stroetzel admits that truly making a medical facility more sustainable is a complex task. “This includes negotiating with manufacturers who often package medical materials in double and triple layers of extra plastic.”

While initiatives such as Stroetzel’s provide much needed information, other experts reason that a wholesale rethinking of healthcare is needed. Voluntary action won’t be enough, and government should set the right example. Kari Nadeau, a Stanford physician who has spent 30 years researching the effects of environmental pollution on the immune system, and Kenneth Kizer, the former undersecretary for health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, wrote in JAMA last year that the medical industry and federal agencies that provide health care should be required to measure and make public their carbon footprints. “Government health systems do not disclose these data (and very rarely do private health care organizations), unlike more than 90% of the Standard & Poor’s top 500 companies and many nongovernment entities," they explained. "This could constitute a substantial step toward better equipping health professionals to confront climate change and other planetary health problems.”

Compared to the U.K., the U.S. healthcare industry lags behind in terms of measuring and managing its carbon footprint, and hospitals are the second highest energy user of any sector in the U.S.

Kizer and Nadeau look to the U.K. National Health Service (NHS), which created a Sustainable Development Unit in 2008 and began that year to conduct assessments of the NHS’s carbon footprint. The NHS also identified its biggest culprits: Of the 2019 footprint, with emissions totaling 25 megatons of carbon dioxide equivalent, 62 percent came from the supply chain, 24 percent from the direct delivery of care, 10 percent from staff commute and patient and visitor travel, and 4 percent from private health and care services commissioned by the NHS. From 1990 to 2019, the NHS has reduced its emission of carbon dioxide equivalents by 26 percent, mostly due to the switch to renewable energy for heat and power. Meanwhile, the NHS has encouraged health clinics in the U.K. to install wind generators or photovoltaics that convert light to electricity -- relatively quick ways to decarbonize buildings in the health sector.

Compared to the U.K., the U.S. healthcare industry lags behind in terms of measuring and managing its carbon footprint, and hospitals are the second highest energy user of any sector in the U.S. “We are already seeing patients with symptoms from climate change, such as worsened respiratory symptoms from increased wildfires and poor air quality in California,” write Thomas B. Newman, a pediatrist at the University of California, San Francisco, and UCSF clinical research coordinator Daisy Valdivieso. “Because of the enormous health threat posed by climate change, health professionals should mobilize support for climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.” They believe “the most direct place to start is to approach the low-lying fruit: reducing healthcare waste and overuse.”

In addition to resulting in waste, the plastic in hospitals ultimately harms patients, who may be even more vulnerable to the effects due to their health conditions. Microplastics have been detected in most humans, and on average, a human ingests five grams of microplastic per week. Newman and Valdivieso refer to the American Board of Internal Medicine's Choosing Wisely program as one of many initiatives that identify and publicize options for “safely doing less” as a strategy to reduce unnecessary healthcare practices, and in turn, reduce cost, resource use, and ultimately reduce medical harm.

A few U.S. clinics are pioneers in transitioning to clean energy sources. In Wisconsin, the nonprofit Gundersen Health network became the first hospital to cut its reliance on petroleum by switching to locally produced green energy in 2015, and it saved $1.2 million per year in the process. Kaiser Permanente eliminated its 800,000 ton carbon footprint through energy efficiency and purchasing carbon offsets, reaching a balance between carbon emissions and removing carbon from the atmosphere in 2020, the first U.S. health system to do so.

Cleveland Clinic has pledged to join Kaiser in becoming carbon neutral by 2027. Realizing that 80 percent of its 2008 carbon emissions came from electricity consumption, the Clinic started switching to renewable energy and installing solar panels, and it has invested in researching recyclable products and packaging. The Clinic’s sustainability report outlines several strategies for producing less waste, such as reusing cases for sterilizing instruments, cutting back on materials that can’t be recycled, and putting pressure on vendors to reduce product packaging.

The Charité Berlin, Europe’s biggest university hospital, has also announced its goal to become carbon neutral. Its sustainability managers have begun to identify the biggest carbon culprits in its operations. “We’ve already reduced CO2 emissions by 21 percent since 2016,” says Simon Batt-Nauerz, the director of infrastructure and sustainability.

The hospital still emits 100,000 tons of CO2 every year, as much as a city with 10,000 residents, but it’s making progress through ride share and bicycle programs for its staff of 20,000 employees, who can get their bikes repaired for free in one of the Charité-operated bike workshops. Another program targets doctors’ and nurses’ scrubs, which cause more than 200 tons of CO2 during manufacturing and cleaning. The staff is currently testing lighter, more sustainable scrubs made from recycled cellulose that is grown regionally and requires 80 percent less land use and 30 percent less water.

The Charité hospital in Berlin still emits 100,000 tons of CO2 every year, but it’s making progress through ride share and bicycle programs for its staff of 20,000 employees.

Wiebke Peitz | Specific to Charité

Anesthesiologist Susanne Koch spearheads sustainability efforts in anesthesiology at the Charité. She says that up to a third of hospital waste comes from surgery rooms. To reduce medical waste, she recommends what she calls the 5 Rs: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Rethink, Research. “In medicine, people don’t question the use of plastic because of safety concerns,” she says. “Nobody wants to be sued because something is reused. However, it is possible to reduce plastic and other materials safely.”

For instance, she says, typical surgery kits are single-use and contain more supplies than are actually needed, and the entire kit is routinely thrown out after the surgery. “Up to 20 percent of materials in a surgery room aren’t used but will be discarded,” Koch says. One solution could be smaller kits, she explains, and another would be to recycle the plastic. Another example is breathing tubes. “When they became scarce during the pandemic, studies showed that they can be used seven days instead of 24 hours without increased bacteria load when we change the filters regularly,” Koch says, and wonders, “What else can we reuse?”

In the Netherlands, TU Delft researchers Tim Horeman and Bart van Straten designed a method to melt down the blue polypropylene wrapping paper that keeps medical instruments sterile, so that the material can be turned it into new medical devices. Currently, more than a million kilos of the blue paper are used in Dutch hospitals every year. A growing number of Dutch hospitals are adopting this approach.

Another common practice that’s ripe for improvement is the use of a certain plastic, called PVC, in hospital equipment such as blood bags, tubes and masks. Because of its toxic components, PVC is almost never recycled in the U.S., but University of Michigan researchers Danielle Fagnani and Anne McNeil have discovered a chemical process that can break it down into material that could be incorporated back into production. This could be a step toward a circular economy “that accounts for resource inputs and emissions throughout a product’s life cycle, including extraction of raw materials, manufacturing, transport, use and reuse, and disposal,” as medical experts have proposed. “It’s a failure of humanity to have created these amazing materials which have improved our lives in many ways, but at the same time to be so shortsighted that we didn’t think about what to do with the waste,” McNeil said in a press release.

Susanne Koch puts it more succinctly: “What’s the point if we save patients while killing the planet?”

The Friday Five: A surprising health benefit for people who have kids

In this week's Friday Five, your kids may be stressing you out, but research suggests they're actually protecting a key aspect of your health. Plus, a new device unlocks the heart's secrets, super-ager gene transplants and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- Kids stressing you out? They could be protecting your health.

- A new device unlocks the heart's secrets

- Super-ager gene transplants

- Surgeons could 3D print your organs before operations

- A skull cap looks into the brain like an fMRI