Wild-Caught Seafood Has Been Notoriously Shady – Until Now

The Dock to Dish model has expanded across North and Central America. Above, artisanal fishermen on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica head out to sea seeking schools of abundant forage fish to supply the program.

In 2012, entrepreneur Sean Barrett founded Dock to Dish in Montauk, New York. It connected local fishermen and women with local chefs, enabling the chefs to serve hyper-fresh seafood – with the caveat that they didn't know what would be on their menus until it arrived in their kitchens the night before.

"Since we're not a seafood-centric culture, people don't know what's what, where fish are from, and when they're in season, making them easy to dupe."

In June of 2017, The United Nations Foundation designated Dock to Dish as one of the top breakthrough innovations that can scale to solve the ocean's grand challenges. His company has since expanded across the Americas and has just opened up shop in Fiji. Leapsmag recently chatted with Barrett about his inspirations and ideas for how to overcome the hurdles of farming wild seafood. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to start Dock to Dish?

The short story is "A Tale of Two Hills."

The first is Quail Hill Farm in Amagansett. I grew up in the commercial fishing port of Chinicock in the 1980's and 90's, working on my family's dock from an early age and in the restaurant industry in my teens. By my thirties, I had accrued my 10,000 hours of experience in both dock and dish. I watched the food system shift from local to global, especially in seafood. By the early 2000's, over 90 percent of seafood in the U.S. was imported. It was bad.

Quail Hill was the first CSA [Community Supported Agriculture, in which customers pay up front for a share in whatever crops grow (or don't) on the farm that season] in the U.S., founded in 1990. So people in the area were accustomed to getting their produce that way. Scott Chaskey, the poet farmer at Quail Hill, really helped crystallize the philosophy for me and inspired me to apply it to seafood. Fishermen had always been bringing a share of their day's catch to their neighbors; now we were just doing it in a more formalized way.

The second is Blue Hill at Stone Barns. [Executive chef and co-owner] Dan Barber literally trademarked the phrase "Know Thy Farmer"; we just expanded it to Know Thy Fisherman and it took off like a rocket ship. His connections in the restaurant world were also indispensable.

17th generation Montauk fisherman Captain Bruce Beckwith (above left) with crew Charlie Etzel (Center) and Jeremy Gould (right).

Do you have any issues that are unique to seafood that a CSA or meat co-op wouldn't face?

This food is WILD. People are totally disconnected from what that word means, and it makes seafood different from everything else. Everything changes when viewed through the prism of that word.

This is the last wild food we eat. It is unpredictable, and subject to variables ranging from currents and tides to which way the wind is blowing. But it is what makes our model so much more impactful and beneficial than the industrialized, demand-driven marketplace that surrounds us. The ocean and its ecosystem are the boss, not chefs and consumers.

There has a been a lot of press about seafood being mislabeled. How and why does that happen? Can Dock to Dish fix it?

Imported, farmed seafood is cheap. Wild, sustainable seafood is not. People are buying low and selling high to make a buck; and while fisheries are extraordinarily regulated, the marketplace isn't. There is no punishment for mislabeling, and no means to correct it. Since we're not a seafood-centric culture, people don't know what's what, where fish are from, and when they're in season, making them easy to dupe. But technology is poised to fix that; DNA testing can test what a fish sample is and where it's from, and SciO handheld spectrometers – soon to be incorporated into smartphones – can analyze the molecular makeup of anything on your plate.

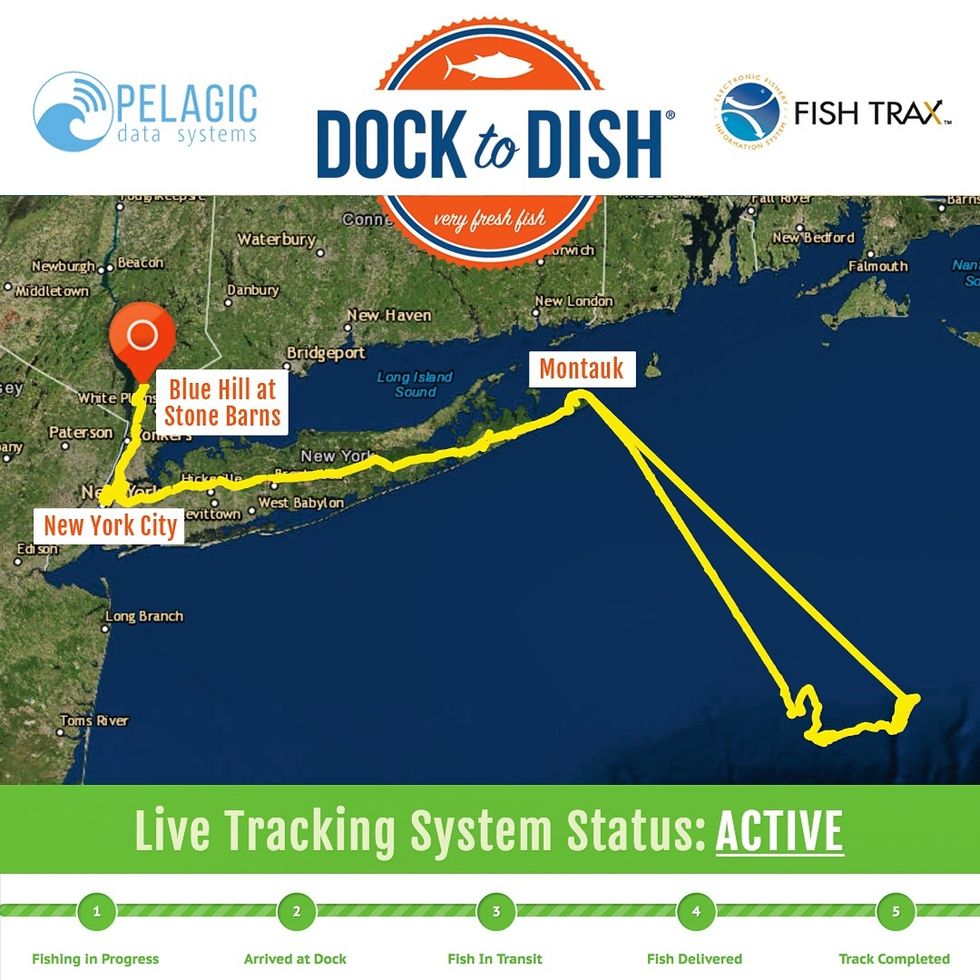

We've created the first ever live tracking system and database for wild fisheries. It is similar to the electronic system used to monitor commercial fisheries, thanks to which the resurgence of wild seafood in U.S. waters is a model for the rest of the world. We have vessel tracking devices on our fishing boats and delivery vans, so the path of each fish is publicly available in real time.

In 2017, Dock to Dish launched the world's first live "end-to-end" tracking system for wild seafood, which provides full chain transparency and next-generation traceability for members.

People are increasingly looking to seafood as a healthier, possibly more sustainable protein option than meat. Can Dock to Dish scale up to accommodate this potentially growing market?

Nope. We can't scale; the supply is finite. That's why the price keeps going up. To avoid becoming "fish for the rich" we are working closely with Greenwave.org to create a network of 3D restorative ocean farms growing kelp and shellfish, which sequester carbon and nitrogen out of the air and soil. Restorative, because sustainable is no longer an option. In fifty years, a plate of seafood will be mostly ocean vegetables with a small amount of finfish as a garnish.

Urinary tract infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year.

Few things are more painful than a urinary tract infection (UTI). Common in men and women, these infections account for more than 8 million trips to the doctor each year and can cause an array of uncomfortable symptoms, from a burning feeling during urination to fever, vomiting, and chills. For an unlucky few, UTIs can be chronic—meaning that, despite treatment, they just keep coming back.

But new research, presented at the European Association of Urology (EAU) Congress in Paris this week, brings some hope to people who suffer from UTIs.

Clinicians from the Royal Berkshire Hospital presented the results of a long-term, nine-year clinical trial where 89 men and women who suffered from recurrent UTIs were given an oral vaccine called MV140, designed to prevent the infections. Every day for three months, the participants were given two sprays of the vaccine (flavored to taste like pineapple) and then followed over the course of nine years. Clinicians analyzed medical records and asked the study participants about symptoms to check whether any experienced UTIs or had any adverse reactions from taking the vaccine.

The results showed that across nine years, 48 of the participants (about 54%) remained completely infection-free. On average, the study participants remained infection free for 54.7 months—four and a half years.

“While we need to be pragmatic, this vaccine is a potential breakthrough in preventing UTIs and could offer a safe and effective alternative to conventional treatments,” said Gernot Bonita, Professor of Urology at the Alta Bro Medical Centre for Urology in Switzerland, who is also the EAU Chairman of Guidelines on Urological Infections.

The news comes as a relief not only for people who suffer chronic UTIs, but also to doctors who have seen an uptick in antibiotic-resistant UTIs in the past several years. Because UTIs usually require antibiotics, patients run the risk of developing a resistance to the antibiotics, making infections more difficult to treat. A preventative vaccine could mean less infections, less antibiotics, and less drug resistance overall.

“Many of our participants told us that having the vaccine restored their quality of life,” said Dr. Bob Yang, Consultant Urologist at the Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, who helped lead the research. “While we’re yet to look at the effect of this vaccine in different patient groups, this follow-up data suggests it could be a game-changer for UTI prevention if it’s offered widely, reducing the need for antibiotic treatments.”

MILESTONE: Doctors have transplanted a pig organ into a human for the first time in history

A surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital prepares a pig organ for transplant.

Surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital made history last week when they successfully transplanted a pig kidney into a human patient for the first time ever.

The recipient was a 62-year-old man named Richard Slayman who had been living with end-stage kidney disease caused by diabetes. While Slayman had received a kidney transplant in 2018 from a human donor, his diabetes ultimately caused the kidney to fail less than five years after the transplant. Slayman had undergone dialysis ever since—a procedure that uses an artificial kidney to remove waste products from a person’s blood when the kidneys are unable to—but the dialysis frequently caused blood clots and other complications that landed him in the hospital multiple times.

As a last resort, Slayman’s kidney specialist suggested a transplant using a pig kidney provided by eGenesis, a pharmaceutical company based in Cambridge, Mass. The highly experimental surgery was made possible with the Food and Drug Administration’s “compassionate use” initiative, which allows patients with life-threatening medical conditions access to experimental treatments.

The new frontier of organ donation

Like Slayman, more than 100,000 people are currently on the national organ transplant waiting list, and roughly 17 people die every day waiting for an available organ. To make up for the shortage of human organs, scientists have been experimenting for the past several decades with using organs from animals such as pigs—a new field of medicine known as xenotransplantation. But putting an animal organ into a human body is much more complicated than it might appear, experts say.

“The human immune system reacts incredibly violently to a pig organ, much more so than a human organ,” said Dr. Joren Madsen, director of the Mass General Transplant Center. Even with immunosuppressant drugs that suppress the body’s ability to reject the transplant organ, Madsen said, a human body would reject an animal organ “within minutes.”

So scientists have had to use gene-editing technology to change the animal organs so that they would work inside a human body. The pig kidney in Slayman’s surgery, for instance, had been genetically altered using CRISPR-Cas9 technology to remove harmful pig genes and add human ones. The kidney was also edited to remove pig viruses that could potentially infect a human after transplant.

With CRISPR technology, scientists have been able to prove that interspecies organ transplants are not only possible, but may be able to successfully work long term, too. In the past several years, scientists were able to transplant a pig kidney into a monkey and have the monkey survive for more than two years. More recently, doctors have transplanted pig hearts into human beings—though each recipient of a pig heart only managed to live a couple of months after the transplant. In one of the patients, researchers noted evidence of a pig virus in the man’s heart that had not been identified before the surgery and could be a possible explanation for his heart failure.

So far, so good

Slayman and his medical team ultimately decided to pursue the surgery—and the risk paid off. When the pig organ started producing urine at the end of the four-hour surgery, the entire operating room erupted in applause.

Slayman is currently receiving an infusion of immunosuppressant drugs to prevent the kidney from being rejected, while his doctors monitor the kidney’s function with frequent ultrasounds. Slayman is reported to be “recovering well” at Massachusetts General Hospital and is expected to be discharged within the next several days.