Would You Eat These Futuristic Foods?

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A rendering of a 3D-printed burger.

Imagine it's 2050. You wake up and make breakfast: fluffy scrambled eggs that didn't come from a chicken, but that taste identical to the ones you remember eating as a kid. You would never know that the egg protein on your plate, ovalbumin, was developed in an industrial bioreactor using fungi.

"We have this freedom to operate, freedom to engineer way beyond what we have now with livestock or plants."

For lunch, you head to your kitchen's 3D printer and pop in a cartridge, select your preferred texture and flavor, then stand back while your meal is chemically assembled. Afterward, for dessert, you snack on some chocolate that tastes more delicious than the truffles of the past. That's because these cocoa beans were gene-edited to improve their flavor.

2050 is not a random year –it's when the United Nations estimates that the world population will have ballooned to nearly 10 billion people. That's a staggering number of mouths to feed. So, scientists are already working on ways to make new food products that are unlike anything we consume today, but that could offer new, potentially improved nutritional choices and sustainable options for the masses. To whet your appetite, here are three futuristic types of food that are currently in development around the world:

1) Cellular Agriculture

Researchers at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, a leading R&D organization in Europe, are on the cutting-edge of developing a whole new ecosystem of food with novel ingredients and novel functionality.

In the high-tech world of cellular agriculture, single-cell organisms can be used in contained environments to produce food ingredients that are identical to traditionally sourced ingredients. For example, whey protein can be developed inside a bioreactor that is functionally the same as the kind in cow's milk.

Ditto for eggs without a chicken – so the world will finally know which came first.

The steel tank bioreactors in VTT´s piloting facility are used to grow larger amounts of plant cells or to brew dairy and egg proteins with microbes.

(VTT)

"We take the gene from a chicken genome, and place that in a microbe, and then the microbe can, with those instructions, make exactly the same protein," explains Lauri Reuter, a Senior Specialist at VTT who holds a doctorate in biotechnology. "It will swim in this bioreactor and kick out the protein, and we get this liquid that can be purified. Then you would cook or bake with it, and the food you would eat tastes and looks like food you would eat right now."

But why settle for what chickens can do? With this technology, it's possible, for example, to modify the ovalbumin protein to decrease its allergenicity.

"This is the power of what we can do with modern tools of genetic engineering," says Christopher Landowski,a Research Team Leader of the Protein Production Team. And the innovative potential doesn't stop there.

"We have this freedom to operate, freedom to engineer way beyond what we have now with livestock or plants," Reuter says. Future foods sourced from cells could include meat analogues, sugar substitutes, dairy substitutes, nutritious veggies that don't taste bitter, personalized nutrition – ingredients designed for individual needs; the list goes on. It could even be used one day to produce food on Mars.

The researchers emphasize the advantages of this method: their living cell factories are efficient – no care of complex animals is required; they can scale up or down in reaction to demand; their environments are contained and don't require antibiotics; and they provide an alternative to using animals.

But the researchers also readily admit that the biggest obstacle is consumer acceptance, which is why they seek to engage with people along the way to alleviate any concerns and to educate them about the technology. Novel foods of this sort have already been eaten in research settings, but it may take another three to five years before the egg and milk proteins hit the market, probably first in the United States before Europe.

Eventually, the researchers anticipate widespread adoption.

Emilia Nordlund, who directs the Food Solutions team, predicts, "Cellular agriculture will revolutionize the food industry as dramatically as the Internet revolutionized many other industries."

Jams made of culture cells of various plants: strawberry, scurvy grass, arctic bramble, tobacco, cloudberry and lingonberry.

(VTT/Lauri Reuter)

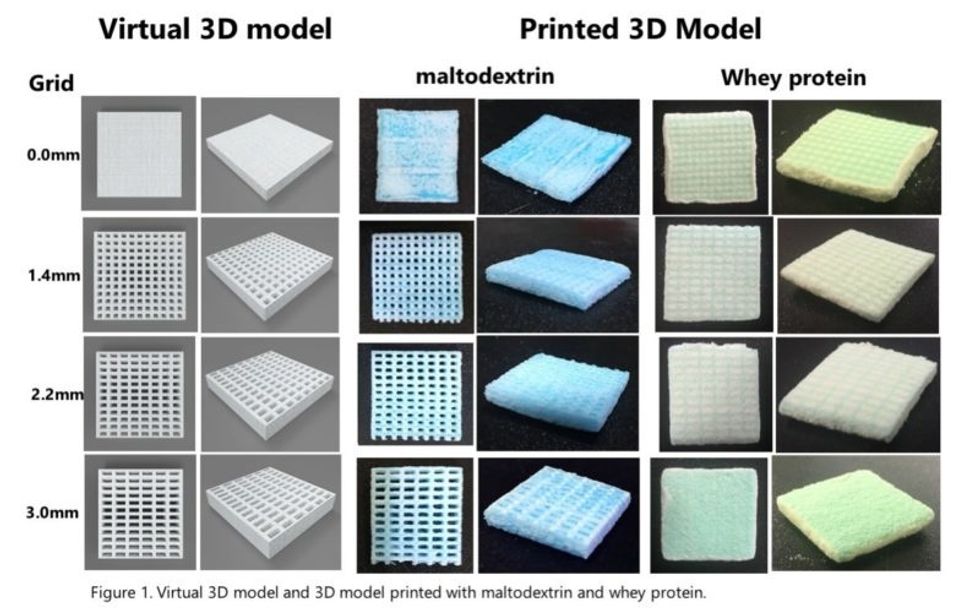

2) 3D-printed foods

In South Korea, researchers are developing 3D-printed foods to help solve a problem caused by aging. Elderly people often rely on soft foods which are easier to chew, but aren't always healthy, like Jello and pudding.

With 3D printing, foods of softer textures can be created with the same nutritional value as firmer food, via a processing method that breaks down the food into tiny nutrients by grinding it at a very low temperature with liquid nitrogen.

"The goal is that someone at home can print out food with whatever flavor and texture they want."

The micro-sized food materials are then reconstructed in layers to form what looks like a Lego block. "The cartridges are all textures, some soft and some stiff," explains Jin-Kyu Rhee, associate professor at Ewha Womans University, whose project has been funded for the last three years by the South Korean government. "We are developing a library of food textures, so that people can combine them to simulate a real type of food."

Users could then add powdered versions of various ingredients to create customized food. Flavor, of course, is of prime importance too, so the cartridges have flavors like barbecue to help simulate the experience of eating "real" food.

"The goal is that someone at home can print out food with whatever flavor and texture they want," Rhee says. "They can order their own cartridge and digital recipes to generate their own food, ready to cook with a microwave oven." It could also be used for space travel.

Rhee expects the prototype of the printer to be completed by the end of this year and will then seek out a commercial partner. If all goes well, you might be able to set up your 3D printer next to your coffee pot by 2025.

3) CRISPR-edited foods

You may not know that the cocoa plant is having a tough time out there in nature. It's plagued by fungal disease; on farms, about 30 to 40 percent of the potential cocoa beans are lost every year. For all the chocolate lovers of the world, this means less to go around.

Conventional plant breeding is very slow for trees, so researchers like Mark Guiltinan at Penn State University are devising ways to increase the plants' chances for survival – without moving any genes between species, as in genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

"Because society hasn't really embraced [GMOs] very much, we're trying to develop ways that don't use transgenic plants and speed up breeding," Guiltinan says.

He and his colleagues are using CRISPR-cas9, the precise method of editing DNA, to imbue cocoa plants with immunity to fungal disease.

How does it work? Similar to humans, the plants have an immune system. Part of it functions like brakes, repressing the whole system so it's only working when it needs to.

"Like when you get a fever, your immune system is working full blast, but your body shuts it down when it doesn't need it," he explains. "Plants do exactly the same thing. One idea is if we can reduce or eliminate that brake on the immune system, we could make plants that have a very high immunity."

A CRISPR-edited npr3 mutant cacao plantlet, not too much to see yet, but soon it will become a happy plant in the greenhouse.

(Photo credit: Mark Guiltinan)

The CRISPR-cas9 system allows "a really amazing little protein" to go into the cocoa plant cell, find a specific gene, and shut it off to put the whole immune system into overdrive. This confers the necessary immunity, and though the plant burns through a lot of energy, as if it has a fever all the time, this method would allow for more plants to fend off the fungal attacks every year. Which means more chocolate. It could also greatly reduce the need for pesticides.

"Replacing chemicals with genetics is one part of our goal," Guiltinan says. "And it's totally safe." Another goal of his project is to improve the cocoa beans' quality and flavor profile through gene editing.

Yum. Is your mouth watering yet?

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Here's how one doctor overcame extraordinary odds to help create the birth control pill

Dr. Percy Julian had so many personal and professional obstacles throughout his life, it’s amazing he was able to accomplish anything at all. But this hidden figure not only overcame these incredible obstacles, he also laid the foundation for the creation of the birth control pill.

Julian’s first obstacle was growing up in the Jim Crow-era south in the early part of the twentieth century, where racial segregation kept many African-Americans out of schools, libraries, parks, restaurants, and more. Despite limited opportunities and education, Julian was accepted to DePauw University in Indiana, where he majored in chemistry. But in college, Julian encountered another obstacle: he wasn’t allowed to stay in DePauw’s student housing because of segregation. Julian found lodging in an off-campus boarding house that refused to serve him meals. To pay for his room, board, and food, Julian waited tables and fired furnaces while he studied chemistry full-time. Incredibly, he graduated in 1920 as valedictorian of his class.

After graduation, Julian landed a fellowship at Harvard University to study chemistry—but here, Julian ran into yet another obstacle. Harvard thought that white students would resent being taught by Julian, an African-American man, so they withdrew his teaching assistantship. Julian instead decided to complete his PhD at the University of Vienna in Austria. When he did, he became one of the first African Americans to ever receive a PhD in chemistry.

Julian received offers for professorships, fellowships, and jobs throughout the 1930s, due to his impressive qualifications—but these offers were almost always revoked when schools or potential employers found out Julian was black. In one instance, Julian was offered a job at the Institute of Paper Chemistory in Appleton, Wisconsin—but Appleton, like many cities in the United States at the time, was known as a “sundown town,” which meant that black people weren’t allowed to be there after dark. As a result, Julian lost the job.

During this time, Julian became an expert at synthesis, which is the process of turning one substance into another through a series of planned chemical reactions. Julian synthesized a plant compound called physostigmine, which would later become a treatment for an eye disease called glaucoma.

In 1936, Julian was finally able to land—and keep—a job at Glidden, and there he found a way to extract soybean protein. This was used to produce a fire-retardant foam used in fire extinguishers to smother oil and gasoline fires aboard ships and aircraft carriers, and it ended up saving the lives of thousands of soldiers during World War II.

At Glidden, Julian found a way to synthesize human sex hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone, from plants. This was a hugely profitable discovery for his company—but it also meant that clinicians now had huge quantities of these hormones, making hormone therapy cheaper and easier to come by. His work also laid the foundation for the creation of hormonal birth control: Without the ability to synthesize these hormones, hormonal birth control would not exist.

Julian left Glidden in the 1950s and formed his own company, called Julian Laboratories, outside of Chicago, where he manufactured steroids and conducted his own research. The company turned profitable within a year, but even so Julian’s obstacles weren’t over. In 1950 and 1951, Julian’s home was firebombed and attacked with dynamite, with his family inside. Julian often had to sit out on the front porch of his home with a shotgun to protect his family from violence.

But despite years of racism and violence, Julian’s story has a happy ending. Julian’s family was eventually welcomed into the neighborhood and protected from future attacks (Julian’s daughter lives there to this day). Julian then became one of the country’s first black millionaires when he sold his company in the 1960s.

When Julian passed away at the age of 76, he had more than 130 chemical patents to his name and left behind a body of work that benefits people to this day.

Therapies for Healthy Aging with Dr. Alexandra Bause

My guest today is Dr. Alexandra Bause, a biologist who has dedicated her career to advancing health, medicine and healthier human lifespans. Dr. Bause co-founded a company called Apollo Health Ventures in 2017. Currently a venture partner at Apollo, she's immersed in the discoveries underway in Apollo’s Venture Lab while the company focuses on assembling a team of investors to support progress. Dr. Bause and Apollo Health Ventures say that biotech is at “an inflection point” and is set to become a driver of important change and economic value.

Previously, Dr. Bause worked at the Boston Consulting Group in its healthcare practice specializing in biopharma strategy, among other priorities

She did her PhD studies at Harvard Medical School focusing on molecular mechanisms that contribute to cellular aging, and she’s also a trained pharmacist

In the episode, we talk about the present and future of therapeutics that could increase people’s spans of health, the benefits of certain lifestyle practice, the best use of electronic wearables for these purposes, and much more.

Dr. Bause is at the forefront of developing interventions that target the aging process with the aim of ensuring that all of us can have healthier, more productive lifespans.