6 Biotech Breakthroughs of 2021 That Missed the Attention They Deserved

A string of the code that comprises a DNA molecule, pictured at Miraikan, the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation in Japan.

News about COVID-19 continues to relentlessly dominate as Omicron surges around the globe. Yet somehow, during the pandemic’s exhausting twists and turns, progress in other areas of health and biotech has marched on.

In some cases, these innovations have occurred despite a broad reallocation of resources to address the COVID crisis. For other breakthroughs, COVID served as the forcing function, pushing scientists and medical providers to rethink key aspects of healthcare, including how cancer, Alzheimer’s and other diseases are studied, diagnosed and treated. Regardless of why they happened, many of these advances didn’t make the headlines of major media outlets, even when they represented turning points in overcoming our toughest health challenges.

If it bleeds, it leads—and many disturbing stories, such as COVID surges, deserve top billing. Too often, though, mainstream media’s parallel strategy seems to be: if it innovates, it fades to the background. But our breakthroughs are just as critical to understanding the state of the world as our setbacks. I asked six pragmatic yet forward-thinking experts on health and biotech for their perspectives on the most important, but under-appreciated, breakthrough of 2021.

Their descriptions, below, were lightly edited by Leaps.org for style and format.

New Alzheimer's Therapies

Mary Carrillo, Chief Science Officer at the Alzheimer’s Association

Alzheimer's Association

One of the biggest health stories of 2021 was the FDA’s accelerated approval of aducanumab, the first drug that treats the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s, not just the symptoms. But, Alzheimer’s is a complex disease and will likely need multiple treatment strategies that target various aspects of the disease. It’s been exciting to see many of these types of therapies advance in 2021.

Following the FDA action in June, we saw renewed excitement in this class of disease-modifying drugs that target beta-amyloid, a protein that accumulates in the brain and leads to brain cell death. This class includes drugs from Eli Lilly (donanemab), Eisai (lecanemab) and Roche (gantenerumab), all of which received Breakthrough Designation by the FDA in 2021, advancing the drugs more quickly through the approval process.

We’ve also seen treatments advance that target other hallmarks of Alzheimer’s this year. We heard topline results from a phase 2 trial of semorinemab, a drug that targets tau tangles, a toxic protein that destroys neurons in the Alzheimer’s brain. Plus, strategies targeting neuroinflammation, protecting brain cells, and reducing vascular contributions to dementia – all funded through the Alzheimer's Association Part the Cloud program – advanced into clinical trials.

The future of Alzheimer’s treatment will likely be combination therapy, including drug therapies and healthy lifestyle changes, similar to how we treat heart disease. Washington University announced they will be testing a combination of both anti-amyloid and anti-tau drugs in a first-of-its-kind clinical trial, with funding from the Alzheimer’s Association.

AlphaFold

Olivier Elemento, Director of the Caryl and Israel Englander Institute for Precision Medicine at Cornell University

Cornell University

AlphaFold is an artificial intelligence system designed by Google’s DeepMind that opens the door to understanding the three-dimensional structures and functions of proteins, the building blocks that make up almost half of our bodies' dry weight. In 2021, Google made AlphaFold available for free and since then, researchers have used it to drive greater understanding of how proteins interact. This is a foundational event in the field of biotech.

It’s going to take time for the benefits from AlphaFold to transpire, but once we know the 3-D structures of proteins that cause various diseases, it will be much easier to design new drugs that can bind to these proteins and change their activity. Prior to AlphaFold, scientists had identified the 3-D structure of just 17 percent of about 20,000 proteins in the body, partly because mapping the structures was extremely difficult and expensive. Thanks to AlphaFold, we’ve now jumped to knowing – with at least some degree of certainty – the protein structures of 98.5 percent of the proteome.

For example, kinases are a class of proteins that modify other proteins and are often aberrantly active in cancer due to DNA mutations. Some of the earliest targeted therapies for cancer were ones that block kinases but, before AlphaFold, we had only a premature understanding of a few hundred kinases. We can now determine the structures of all 1,500 kinases. This opens up a universe of drug targets we didn’t have before.

Additional progress has been made this year toward potentially using AlphaFold to develop blockers of certain protein receptors that contribute to psychiatric illnesses and other neurological diseases. And in July, scientists used AlphaFold to map the dimensions of a bacterial protein that may be key to countering antibiotic resistance. Another discovery in May could be essential to finding treatments for COVID-19. Ongoing research is using AlphaFold principles to create entirely new proteins from scratch that could have therapeutic uses. The AlphaFold revolution is just beginning.

Virtual First Care

Jennifer Goldsack, CEO of Digital Medicine Society

Digital Medicine Society

Imagine a new paradigm of healthcare defined by how good we are at keeping people healthy and out of the clinic, not how good we are at offering services to a sick person at the clinic. That is the promise of virtual-first care, or V1C, what I consider to be the greatest, and most underappreciated, advance that occurred in medicine this year.

V1C is defined as medical care accessed through digital interactions where possible, guided by a clinician, and integrated into a person’s everyday life. This type of care includes spit kits mailed for laboratory tests and replacing in-person exams with biometric sensors. It’s built around the patient, not the clinic, and provides us with the opportunity to fundamentally reimagine what good healthcare looks like.

V1C flew under the radar in 2021, eclipsed by the ongoing debate about the value of telehealth more broadly as we emerge from the pandemic. However, the growth in the number of specialty and primary care virtual-first providers has been matched only by the number of national health plans offering virtual-first plans. Our own virtual-first community, IMPACT, has tripled in size, mirroring the rapid growth of the field driven by patient demand for care on their terms.

V1C differs from the ‘bolt on’ approach of video visits as an add-on to traditional visit-based, episodic care. V1C takes a much more holistic approach; it allows individuals to initiate care at any time in any place, recognizing that healthcare needs extend beyond 9-5. It matches the care setting with each individual’s clinical needs and personal preferences, advancing a thorough, evidence-based, safe practice while protecting privacy and recognizing that patients’ expectations have changed following the pandemic. V1C puts the promise of digital health into practice. This is the blueprint for what good healthcare looks like in the digital era.

Digital Clinical Trials

Craig Lipset, Founder of Clinical Innovation Partners and former Head of Clinical Innovation at Pfizer

Craig Lipset

In 2021, a number of digital- and data-enabled approaches have sustained decentralized clinical trials around the world for many different disease types. Pharma companies and clinical researchers are enthusiastic about this development for good reason. Throughout the pandemic, these decentralized trials have allowed patients to continue in studies with a reduced need for site visits, without compromising their safety or data quality.

Risk-based monitoring was deployed using data and thoughtful algorithms to identify quality and safety issues without relying entirely on human monitors visiting research sites. Some trials used digital measures to ensure high quality data on target health outcomes that could be captured in ways that made the participants’ physical location irrelevant. More than three-quarters of research organizations, such as pharma and biotech, have accelerated their decentralized clinical trial strategies. Before COVID-19, 72 percent of trial sites “rarely or never” used telemedicine for trial participants; during COVID, 64 percent “sometimes, often or always” do.

While the research community does appreciate the tremendous hope and promise brought by these innovations, perhaps what has been under-appreciated is the culture shift toward thoughtful risk-taking and a willingness to embrace and adopt clinical trial innovations. These solutions existed before COVID, but the pandemic shifted the perception of risks versus benefits involved in these trials. If there is one breakthrough that is perhaps under-appreciated in life sciences clinical research today, it’s the power of this new culture of willingness and receptivity to outlast the pandemic. Perhaps the greatest loss to the research ecosystem would be if we lose the momentum with recent trial innovations and must wait for another global pandemic in order to see it again.

Designing Biology

Sudip Parikh, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and Executive Publisher of the Science family of journals

American Association for the Advancement of Science

As our understanding of basic biology has grown, we are fast approaching an era where it will be possible to design and direct biological machinery to create treatments, medicine, and materials. 2021 saw many breakthroughs in this area, three of which are listed below.

The understanding of the human microbiome is growing as is our ability to modify it. One example is the movement toward the notion of the “bug as the drug.” In June, scientists at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital published a paper showing that they had genetically engineered yeast – using CRISPR/Cas9 – to sense and treat inflammation in the body to relieve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in mice. This approach could potentially be used to address issues with your microbiome to treat other chronic conditions.

Another way in which we saw the application of basic biology discoveries to real world problems in 2021 is through groundbreaking research on synthetic biology. Several institutions and companies are pursuing this path. Ginkgo Bioworks, valued at $15 billion, already claims to engineer cells with assembly-line efficiency. Imagine the possibilities of programming cells and tissue to perform chemistry for the manufacturing process, inspired by the way your body does chemistry. That could mean cleaner, more controllable, and affordable ways to manufacture food, therapeutics, and other materials in a factory-like setting.

A final example: consider the possibility of leveraging the mechanics of your own body to deliver proteins as treatments, vaccines, and more. In 2021, several scientists accelerated research to apply the mRNA technology underlying COVID-19 vaccines to make and replace proteins that, when they’re missing or don’t work, cause rare conditions such as cystic fibrosis and multiple sclerosis.

These applications of basic biology to solve real world problems are exciting on their own, but their convergence with incredible advances in computing, materials, and drug delivery hold the promise of game-changing progress in health care and beyond.

Brain Biomarkers

David R. Walt, Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Wyss Institute at Harvard University

David Walt

2021 brought the first real hope for identifying biomarkers that can predict neurodegenerative disease. Multiple biomarkers (which are measurable indicators of the presence or severity of disease) were identified that can diagnose disease and that correlate with disease progression. Some of these biomarkers were detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) but others were measured directly in blood by examining precursors of protein fibers.

The blood-brain barrier prevents many biomolecules from both exiting and entering the brain, so it has been a longstanding challenge to detect and identify biomarkers that signal changes in brain chemistry due to neurodegenerative disease. With the advent of omics-based approaches (an emerging field that encompasses genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics), coupled with new ultrasensitive analytical methods, researchers are beginning to identify informative brain biomarkers. Such biomarkers portend our ability to detect earlier stages of disease when therapeutic intervention could be effective at halting progression.

In addition, these biomarkers should enable drug developers to monitor the efficacy of candidate drugs in the blood of participants enrolled in clinical trials aimed at slowing neurodegeneration. These biomarkers begin to move us away from relying on cognitive performance indicators and imaging—methods that do not directly measure the underlying biology of neurodegenerative disease. The identity of these biomarkers may also provide researchers with clues about the causes of neurodegenerative disease, which can serve as new targets for drug intervention.

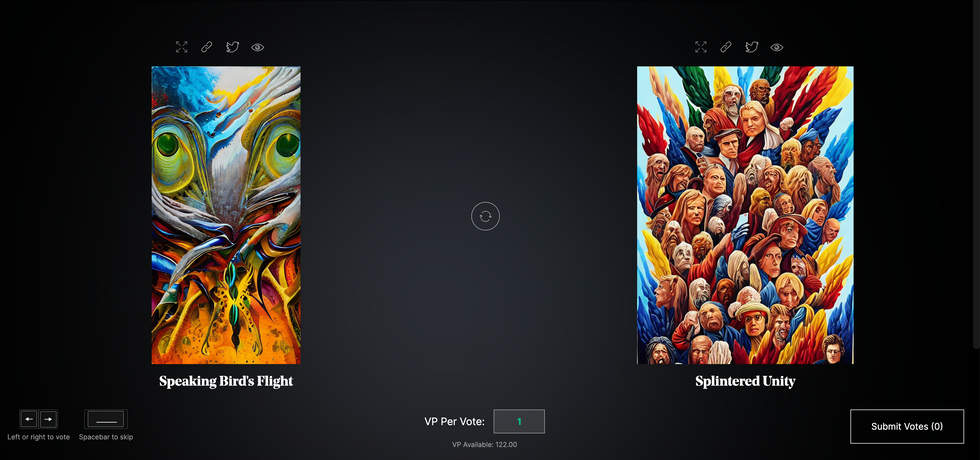

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

When graduating college this month, many North American engineering students will take a special pledge, with a history dating back to 1925.

This spring, just like any other year, thousands of young North American engineers will graduate from their respective colleges ready to start erecting buildings, assembling machinery, and programming software, among other things. But before they take on these complex and important tasks, many of them will recite a special vow stating their ethical obligations to society, not unlike the physicians who take their Hippocratic Oath, affirming their ethos toward the patients they would treat. At the end of the ceremony, the engineers receive an iron ring, as a reminder of their promise to the millions of people their work will serve.

The ceremony isn’t just another graduation formality. As a profession, engineering has ethical weight. Moreover, engineering mistakes can be even more deadly than medical ones. A doctor’s error may cost a patient their life. But an engineering blunder may bring down a plane or crumble a building, resulting in many more fatalities. When larger projects—such as fracking, deep-sea mining or building nuclear reactors—malfunction and backfire, they can cause global disasters, afflicting millions. A vow that reminds an engineer that their work directly affects humankind and their planet is no less important than a medical oath that summons one to do no harm.

The tradition of taking an engineering oath began over a century ago in Canada. In 1922, Herbert E.T. Haultain, professor of mining engineering at the University of Toronto, presented the idea at the annual meeting of the Engineering Institute of Canada. The seven past presidents of that body were in attendance, heard Haultain’s speech and accepted his suggestion to form a committee to create an honor oath. Later, they formed the nonprofit Corporation of the Seven Wardens, which would oversee the ritual. Next year, in 1923, with the encouragement of the Seven Wardens, Haultain wrote to poet and writer Rudyard Kipling, asking him to develop a professional oath for engineers. “We are a tribe—a very important tribe within the community,” Haultain said in the letter, “but we are lacking in tribal spirit, or perhaps I should say, in manifestation of tribal spirit. Also, we are inarticulate. Can you help us?”

While Kipling is most famous now for “The Jungle Book” and perhaps his poem “Gunga Din,” he had also written a short story about engineers, “The Bridge Builders.” His poem “The Sons of Martha” can be read as a celebration of engineers:

It is their care in all the ages to take the buffet and cushion the shock.

It is their care that the gear engages; it is their care that the switches lock.

It is their care that the wheels run truly; it is their care to embark and entrain,

Tally, transport, and deliver duly the Sons of Mary by land and main.

Kipling accepted the ask and wrote the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer, which he sent to Haultain a month later. In his response to Haultain, he stated that he preferred the word “Obligation” to “Oath.” He wrote the Obligation using Old English lettering and the old-fashioned capitalization. Kipling’s Obligation binds engineers upon their “Honor and Cold Iron” to not “suffer or pass, or be privy to the passing of, Bad Workmanship or Faulty Material,” and pardon is asked “in the presence of my betters and my equals in my Calling” for the engineer’s “assured failures and derelictions.” The hope is that when one is tempted to shoddy work by weakness or weariness, the memory of the Obligation “and the company before whom it was entered into, may return to me to aid, comfort, and restrain.”

Using the Obligation, The Seven Wardens created an induction ceremony, which seeks to unify the profession and recognize engineering’s ethics, including responsibility to the public and the need to make the best decisions possible. The induction ceremony included recitation of Kipling’s “Obligation” and incorporated an anvil, a hammer, an iron chain, and an iron ring. The inductee engineers sat inside an area marked off by the iron chain, with their more senior colleagues outside that area. At the start of the ritual, the leader beat out S-S-T in Morse code with the hammer and anvil—the letters standing for Steel, Stone, and Time. A more experienced and previously obligated engineer placed the ring on the small finger of the inductee engineer’s working hand. As per Kipling, the ring’s rough, faceted texture symbolized “the young engineer’s mind” and the difficulties engineers face in mastering their discipline.

A persistent myth purports that the original iron rings were made from the beams or bolts of the Quebec Bridge that failed twice during construction.

The first induction ceremony took place on April 25, 1925, in Montreal to obligate two of the Seven Wardens, along with four graduates from the University of Toronto class of 1893. On May 1 of that year, 14 more engineers were obligated at the University of Toronto. From that time to today most Canadian professional engineers have gone through that same ritual in their various camps, called Kipling camps—local chapters associated with various Canadian universities.

Henry Petroski, Duke University’s professor of civil engineering and history, notes in his book, “Forgive Design: Understanding Failure,” that Kipling’s poem “Sons of Martha” is often read as part of the ritual. However, sometimes inductees read Kipling’s “Hymn of Breaking Strain,” instead, which graphically depicts disastrous outcomes of engineering mistakes. The first stanza of that poem says:

The careful text-books measure

(Let all who build beware!)

The load, the shock, the pressure

Material can bear.

So, when the buckled girder

Lets down the grinding span,

'The blame of loss, or murder,

Is laid upon the man.

Not on the Stuff—the Man!

As if to strengthen the importance of these concepts, a persistent myth purports that the original iron rings were made from the beams or bolts of the Quebec Bridge that failed twice during construction. The bridge spans the St. Lawrence River upriver from Quebec City, and at the time of its construction was the world’s longest at 1,800 feet. Due to engineering errors and poor oversight, the bridge’s own weight exceeded its carrying capacity. Moreover, engineers downplayed danger when bridge beams began to warp under stress, saying that they were probably warped before they were installed. On August 29, 1907, the bridge collapsed, killing 75 of 86 workers. A second collapse occurred in 1916 when lifting equipment failed, and thirteen more workers died.

The ring myth, however, couldn’t be true. The original iron rings couldn’t have come from the failed bridge since it was made of steel, not wrought iron. Today the rings are made from stainless steel because iron deteriorates and stains engineers’ finger black.

On August 14, 2018, Morandi Bridge over Polcevera River in Genoa, Italy, collapsed from structural failure, killing 43 people.

Adobe Stock

The Seven Wardens decided to restrict the ritual to engineers trained in Canada. They copyrighted the obligation oath in Canada and the United States in 1935. Although the ritual is not a requirement for professional licensing, just like the Hippocratic Oath is not part of medical licensing, it remains a long-standing tradition.

The American Obligation of the Engineer has its own creation story, albeit a very different one. The American Order of the Engineer (OOE) was initiated in 1970, during the era of the anti-war protests, Apollo missions and the first Earth Day. On May 4, 1970, the National Guard shot into a crowd of protesters at Kent State University, killing four people. The two authors of the American obligation—Cleveland State University’s (CSU) engineering professor John Janssen and his wife Susan—reflected these historical events in the oath they wrote. Their version of the oath binds engineers to “practice integrity and fair dealing.” It also notes that their “skill carries with it the obligation to serve humanity by making the best use of the Earth’s precious wealth.” As Petroski explains in his book, “campus antiwar protestors around the country tended to view engineers as complicit in weapons proliferation [which] prompted some [CSU] engineering student leaders to look for a means of asserting some more positive values.”

Kip A. Wedel, associate professor of history and politics at Bethel College, wrote in his book, “The Obligation: A History of the Order of the Engineer,” that the ceremony was not a direct response to the Kent State shootings—it was already scheduled when the shootings happened. Yet, engineering students found the ceremony a positive action they could take in contrast to the overall turmoil. The first American ritual took place on June 4, 1970, at CSU. In total, 170 students, faculty members, and practicing engineers took the obligation. This established CSU as the first Link of the Order, as the OOE designates its local chapters. For their first ceremony, the CSU students fabricated smooth, unfaceted rings from stainless steel pipe. Later they were replaced by factory-made rings. According to Paula Ostaff, OOE’s Executive Director, about 20,000 eligible students and alumni obligate themselves yearly.

Societies hope that every engineer is imbued with a strong ethical sense and that their pledges are never far from mind. For some, the rings they wear serve a daily reminder that every paper they sign off on is touched by a physical reminder of their commitment.

These ethical and responsible engineering practices are especially salient today, when one in three American bridges needs repair or replacement, some have already collapsed, and engineers are working on projects related to the bipartisan infrastructure bill President Biden signed into law in 2021. Canada has committed $33 billion to its Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program. At the heart of these grand projects are many thousands of professional engineers, collectively working millions of hours. The professional vows they took aim to assure that the homes, bridges and airplanes they build will work as expected.