A Star Surgeon Left a Trail of Dead Patients—and His Whistleblowers Were Punished

Dr. Paolo Macchiarini, then a professor of Regenerative Medicine at Karolinska Institute in Stockholm (Sweden), looks on during a plenary session at the Science of the Future international scientific conference, on September 17, 2014.

[Editor's Note: This is the first comprehensive account of the whistleblowers' side of a scandal that rocked the most hallowed halls in science – the same establishment that just last week awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. This still-unfolding saga is a cautionary tale about corruption, hype, and power that raises profound questions about how to uphold integrity in scientific research.]

When the world-famous Karolinska Institutet (KI) in Stockholm hired Dr. Paolo Macchiarini, he was considered a star surgeon and groundbreaking stem cell researcher. Handsome, charming and charismatic, Macchiarini was known as a trailblazer in a field that holds hope for curing a vast array of diseases.

It appeared that Macchiarini's miracle cure was working just as expected.

He claimed that he was regenerating human windpipes by seeding plastic scaffolds with stem cells from the patient's own bone marrow—a holy grail in medicine because the body will not reject its own cells. For patients who had trouble breathing due to advanced illness, a trachea made of their own cells would be a game-changer. Supposedly, the bone marrow cells repopulated the synthetic scaffolds with functioning, mucus-secreting epithelial cells, creating a new trachea that would become integrated into the patient's respiratory system as a living, breathing part. Macchiarini said as much in a dazzling presentation to his new colleagues at Karolinska, which is home to the Nobel Assembly – the body that has awarded the Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine since 1901.

Karl-Henrik Grinnemo was a young cardiothoracic surgeon and researcher at Karolinska in 2010, when Macchiarini was hired. "He gave a fantastic presentation with lots of animation and everyone was impressed," Grinnemo says of his first encounter with Macchiarini. Grinnemo's own work focused on heart and aortic valve regeneration, also in the field of stem cell research. He and his colleagues were to help establish an interdisciplinary umbrella organization, under Macchiarini's leadership, called the Advanced Center for Translational Regenerative Medicine, which would aim to deliver cures from Karolinska's world-class laboratories to the bedsides of patients in desperate need.

Little did Grinnemo know that when KI hired Macchiarini, they had ignored a warning that the star surgeon had been accused of scientific misconduct by a colleague who had worked with him at the University of Florence. That blind eye would eventually cost three patients their lives in Sweden.

"A MIRACLE CURE"?

It has been said that if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail, and it wasn't long before Macchiarini announced that he had a patient in dire need of one of the new artificial tracheas. The patient, a native of Eritrea who had emigrated to Iceland, had a slowly growing tumor on his trachea. Macchiarini had previously generated new windpipes from human donor tracheas outside of Sweden, but the Icelandic patient was the first to receive a synthetic trachea implant at Karolinska University Hospital. Macchiarini had already performed a similar procedure with decellularized donor tracheas on other patients around Europe, but not much was known at the time about their outcomes.

Of course, to justify a radical procedure such as removing a patient's trachea, one would need compelling evidence of effectiveness in animal studies, as well as an exhaustion of all other treatment alternatives. Macchiarini claimed that both conditions were met. He performed the implantation of the synthetic trachea as if he had received a hospital exemption. This is comparable to what the U.S. Food and Drug Administration classifies as "compassionate use," a procedure performed only in extreme circumstances, usually when the patient is terminal, and when no available alternative has worked.

Macchiarini personally invited Grinnemo to watch the all-day surgery, and, once the transplant was done after 10 grueling hours, Macchiarini asked him to close the patient. Then the 36-year-old man was transferred to another hospital, where Grinnemo and other attending physicians had little opportunity to follow his long-term recovery.

Two months later, Macchiarini approached Grinnemo with an invitation to be one of multiple co-authors on a paper about the case targeted for the New England Journal of Medicine. This was a huge opportunity for a junior researcher, and Grinnemo gladly agreed to write a one-month follow-up report on the Icelandic patient's clinical condition. He consulted the patient's medical records, which described a man with an infection in one lung but otherwise doing well, and wrote up his contribution. The patient had already been transferred back to Iceland by then and was home from the hospital. It appeared that Macchiarini's miracle cure was working just as expected.

But the ground was beginning to shake.

"We cannot find one word of evidence that points to regeneration induced by stem cells."

On September 2, 2011, three months after the Icelandic patient's surgery, a professor in Leuven, Belgium sent a written warning to KI's vice chancellor, Harriett Wallberg-Henriksson, stating that Macchiarini was guilty of prior research misconduct. This letter was forwarded to the new president at KI, professor Anders Hamsten, urging him to put a halt to more synthetic trachea implants. The accusations were grave.

Professor Pierre Delaere at Kathiolieke Universiteit asserted that synthetic tracheas coated with bone marrow cells did not, as Macchiarini had claimed, transform into living tracheas. He cited "countless" failures in animal experiments and called the outcome of Macchiarini's previous human surgeries "disastrous…half the patients died. The others are in a palliative setting….We cannot find one word of evidence that points to regeneration induced by stem cells."

Once again, KI simply ignored the warning, and Grinnemo and the 24 co-authors on the splashy academic paper about the latest surgery didn't even know about it. In the meantime, the New England Journal of Medicine rejected it for lacking a longer follow-up on the patients and missing data on how well the implants had integrated with the patient's respiratory system, so Macchiarini submitted it to The Lancet instead.

And he kept performing his experimental surgeries.

Soon there was a second transplant patient, a 30-year-old American man named Christopher Lyles. After his operation at KI, he returned to the U.S and the Swedish doctors were unable to follow his progress. Three months after his surgery, they learned that he had died at his home.

Paolo Macchiarini with Christopher Lyles, the American patient on whom he performed a trachea transplant in Stockholm in 2011. Lyles died a few months later.

Only four months after Lyles died, the third patient, a 22-year-old Turkish woman, received one of Macchiarini's grafts. In all three patients, Macchiarini had claimed that they were in dire straights—terminal if not for the hope of a trachea transplant, and he claimed a hospital exemption in all three cases. In fact, Grinnemo says, all three had been in stable condition before their surgeries—a reality Macchiarini did not share with his collaborators and co-authors on two academic papers about the surgeries that were subsequently published in The Lancet.

The Turkish woman's story is especially tragic. The young woman had initially undergone surgery elsewhere to fix an unrelated problem—hand sweating--but wound up with an accidentally damaged trachea that set her on a course of utter devastation. She sought help from Macchiarini, but his graft operation left her "living in hell," says Grinnemo. In intensive care afterward, her airways were producing so much mucus that they had to be cleared every four hours around the clock. The procedure "is like someone keeping your head under water every fourth hour until you almost suffocate to death. This is something that you wouldn't wish on your worst enemy," says Grinnemo.

By the spring of 2013, six months after Macchiarini's operation, the graft began to collapse. Several metal stents were inserted into her airways, but each one only worked for a short while. Macchiarini decided to remove the first plastic trachea and implant a new one. It seemed she couldn't get any worse, but after the second transplant, the young woman further deteriorated. Her airway secretions only increased; she had to undergo thousands of bronchoscopies, where an instrument was pushed down her throat into her lungs, and hundreds of surgeries during her three-year stint in the intensive care unit. Her body couldn't tolerate much more.

The whistleblowers realized that, despite Macchiarini's claims of successful operations in several now-published papers, the patients had been mutilated.

Grinnemo, together with fellow KI physicians Matthias Corbascio, Oscar Simonson and Thomas Fux, who were all involved in the care of the Turkish woman, became alarmed when the Icelandic patient came back to their hospital in the fall of 2013 with similar complaints. They realized that, despite Macchiarini's claims of successful operations in several now-published papers, the patients had been mutilated.

Both the Icelandic patient and the Turkish woman were too incapacitated to speak for themselves, so in the late fall of 2013, Grinnemo and his three concerned colleagues reached out to the patients' relatives seeking permission to review their medical records. It took weeks to receive the permissions, but once they did, what they found stunned them.

The Icelandic patient had developed fistulas (holes) between the artificial trachea and his esophagus, and had been fitted with several stents. Soon his esophagus also had to be removed, which Macchiarini was aware of. He should have reported these complications in the articles on which he was lead author, Grinnemo contends, and also should have informed his co-authors, each of whom had been responsible for writing up discrete sections of the papers. But Macchiarini had described each transplant as a success and had greatly exaggerated, if not outright lied, about how each patient had fared.

THE WHISTLEBLOWERS FIGHT BACK

Grinnemo and several other suspicious colleagues decided to launch an investigation. The result was a 500-page report identifying the synthetic tracheas as the problem and revealing that Macchiarini had falsified data and suppressed critical information in his reporting. He had even invented biopsies of the grafts, claiming that the marrow cells had populated them with functioning epithelial cells, while there was no real evidence of the patients' cells growing to line the tracheas.

The whistleblowers also discovered that Macchiarini had never received ethical clearance from Sweden's Human Ethical Review Board, nor had he gotten approval for his plastic tracheas from the Medical Product Agency, the Swedish counterpart to the FDA. He had relied entirely on his ability to do the surgeries under the hospital exemption, which he made everyone believe that he had obtained thanks to his star power.

What Macchiarini was doing, the investigators realized, was experimentation on living human subjects; he had circumvented the normal oversight protocols that exist to protect such subjects.

At a procedural meeting with his colleagues, including Dr. Ulf Lockowandt, the head of Karolinska University Hospital's Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Macchiarini dismissed the patients' complications as "manageable."

But among the large interdisciplinary team whose members had knowledge only of their own discrete specialties, doubts about Macchiarini's technique were festering. Complications in the patients only worsened when the tracheas inevitably began to collapse. There was a bursting open of sutures, holes in tissues adjacent to the implants, the disintegration of tissues that clogged bronchial passages. In far more than half of all the patients Macchiarini had operated on in several countries, patients died a lingering and agonizing death.

The last thing the whistleblowers expected was for the full weight of the institution to come crashing down against them.

When Grinnemo and his fellow investigators dug all this up, they decided they had to report it to the very top of Karolinska, to the institute's president, Anders Hamsten, so that he could stop Macchiarini from performing any further transplants. The last thing the whistleblowers expected was for the full weight of the institution to come crashing down against them.

"THEY WANTED TO SILENCE EVERYTHING"

KI had ample reason to sweep criticisms of Macchiarini under the rug. Up to 100 patients were about to be recruited for an international clinical study in which Macchiarini would do his implants—a nightmarish prospect considering his track record. But KI stood to receive millions of dollars in a government grant to conduct the study across Europe and Russia.

Still other incentives existed for KI to suppress Macchiarini's record. Plans were underway to establish a stem cell center in Hong Kong with over $45 million provided by a wealthy Chinese businessman. At the center, Macchiarini would be able to do his trachea transplants on patients in Asia. And in addition to the financial incentives to keep Macchiarini's brand associated with KI, many high-powered individuals were involved in his initial recruitment and didn't want their reputations tarnished, Grinnemo says. KI not only ignored the whistleblowers' allegations; punishment against them was swift and decisive.

On March 7, 2014, Grinnemo and the other whistleblowers met with Dr. Hamsten, in addition to two of Macchiarini's supervisors and the director of KI's Regenerative Network. They presented their findings and requested an official investigation by KI, including scrutiny of the now-six published research papers in which Macchiarini had claimed the success of his implants in humans. The whistleblowers also told the leadership about some rat studies Macchiarini had published in a prestigious journal that appeared to rely on falsified data.

Instead of the welcoming reception they expected, the room bristled with hostility. "I basically forced them to agree to an investigation," Grinnemo says, "but it was a very tough meeting. The feeling I got was that they wanted to silence everything and that they would continue to silence me and the other whistleblowers. We were already feeling the backlash."

From the left, whistleblowers Matthias Corbascio, Oscar Simonson, Thomas Fux and Karl-Henrik Grinnemo.

Previously, Grinnemo had confronted Macchiarini with questions about patients he had implanted in Russia prior to his stint at Karolinska. "Paolo Macchiarini realized we were onto something and he became very angry. He said he would do everything in his power to make my life miserable," Grinnemo recalls.

Macchiarini made good on his threat by filing a complaint about Grinnemo with the Swedish Research Council, the main funder of research in Sweden. At the time, Macchiarini and Grinnemo had jointly submitted a grant application on an aortic valve regeneration project, which the Council had approved. Macchiarini suddenly complained that Grinnemo had stolen his data on aortic valve regeneration, even though, unlike Grinnemo, Macchiarini was not a heart surgeon and had conducted no research on heart structures. In reality, all of the data had been generated by Grinnemo. The Council did a review and concluded that Grinnemo had not stolen the data, but Macchiarini spread rumors throughout KI that the young researcher was guilty of scientific misconduct. "He wanted to discredit me because he knew I was dangerous and he wanted to stop anyone from believing me," Grinnemo says.

In spite of the findings from the Council that he had committed no scientific misconduct, KI opened an investigation—not of Macchiarini, but of Grinnemo himself. It soon became clear that KI also wanted to discredit Grinnemo and to silence any possible rumors about Macchiarini's conduct. The whistleblowers continued to push forward, however, and over a period of several weeks they wrote to president Hamsten four times, asking that KI investigate the deadly transplants still being promoted by Macchiarini as some kind of miracle cure.

After four written requests, Hamsten replied that if the whistleblowers had concerns about Macchiarini, they should contact their supervisors or write a formal complaint. But the whistleblowers had already contacted several individuals in supervisory roles who had made it clear that they wanted nothing to do with the affair. It was obvious that KI would resist any investigation of Macchiarini and that no one, outside of the whistleblowers, wanted to take any responsibility for what could amount to a major scandal at one of the world's most powerful academic institutions.

The whistleblowers had another hostile and unproductive meeting with several doctors at KI with whom they shared a letter they had written to the journal Nature Communications, which published Macchiarini's article on rat experimentation, urging them to investigate whether he had falsified the data. Once again, the whistleblowers met with a wall of resistance. Grinnemo was now discredited because of the aortic valve grant application, the doctors reminded him, and no investigation or retraction of the Nature Communications article would be pursued.

In June 2014, KI made its retaliation against Grinnemo official by putting its legal counsel in charge of its investigation of his grant application. The university's ethical board then concluded that Grinnemo should have informed Macchiarini more clearly that he submitted the application to the Swedish Research Council and that he should have obtained a written acceptance from Macchiarini before proceeding with the application. KI could not find Grinnemo guilty of research misconduct, but accused him of "carelessness" regarding the usage of data—which was his own data all along.

A few years later, Grinnemo was totally cleared by both the Central Ethical Review Board and KI. However, the rumors surrounding the investigation and the finding that he hadn't "used data correctly" in a grant application had done their damage to his reputation. Since then, he has not received a single research grant. "You can't appeal the findings," Grinnemo says. "I don't know if I will ever get more research money. I'm totally dead."

The whistleblowers made multiple appeals to Dr. Lockowandt, the head of the Department of Cardiothoracic surgery, for an investigation into Macchiarini's implants, but they were stonewalled from the beginning. Lockowandt did nothing.

"The heads of departments at the KUH and KI didn't actually have that much power," Grinnemo explains. "Dr. Lockowandt thought he was fighting for his own career and position. He's basically a good person who decided to go the route of an administrator, and if you have conflicts with your superiors, your career will be over." In other words, a real investigation of Macchiarini's record could not happen with so much money and prestige riding on the continued presence of the star surgeon.

By August 11, 2014, the whistleblowers had made repeated requests of Dr. Hamsten for a meeting to present the data inconsistencies between Macchiarini's patients' medical records and what he had reported in numerous articles, all published in prestigious medical journals. When they finally received the answer—a cold instruction to submit a written notification to the heads of their departments—it was clear that KI was giving them the runaround.

But rather than simply ignore the whistleblowers, KI apparently decided to double down, trying to discredit them in an intimidation campaign.

KI even went so far as to force the chief medical officer of Karolinska University Hospital, Johan Bratt, to report the whistleblowers to Swedish police, claiming that they violated the law and the patients' privacy when they went through the patients´ charts and submitted their appeals for investigation to KI and the Central Ethical Review Board. KI claimed that their report revealed the identities of patients, even though they had been careful to anonymize all the information. The police interrogated several of the whistleblowers and concluded that they had done no wrong, but the incident made it clear how low KI would sink in its desire to harass them.

"You can't appeal the findings. I don't know if I will ever get more research money. I'm totally dead."

In private, Grinnemo's colleagues supported him, but feared coming forward out of the fear of losing their jobs. Grinnemo himself was in a tough spot. "I knew it would be difficult for me to do research but I hoped my position as a surgeon was secure," he says. "But after the New York Times article, I realized even that position was not as safe as I had thought."

THE MEDIA CATCHES ON -- WITH A PRICE

On November 24, 2014, The New York Times published a front-page story about Paolo Macchiarini based on the whistleblowers' investigation, which had leaked to the press. Officials at KI suspected one or more of the whistleblowers of being the leakers, but the publicity forced the top brass to at least appear to act. The next day they asked Dr. Bengt Gerdin, a professor of surgery at Sweden's Uppsala University, to do an investigation of Dr. Macchiarini. It's hard not to conclude that, after months of stonewalling on an institutional investigation, the Times article compelled them to do something. But KI still did not take any of the pressure off of Grinnemo and his three fellow whistleblowers.

One by one, each was informed that he would receive a formal warning from Dr. Lockowandt, the head of the cardiothoracic clinic, alleging that they had violated patient privacy by reading medical records. The whistleblowers countered that they had informed consents. They also asked for a meeting with Lockowandt and KI's attorneys, to which they brought a union representative and someone from the Swedish version of the American Medical Association. The union representative informed KI's attorneys that the doctors were actually required by law to consult a patient's medical records when the patient's life is in danger. Not doing so would have been a crime. Karolinska backed off on the formal warnings (which would have been the last step before actual termination) after that. But they found other ways to retaliate.

One whistleblower, Oscar Simonson, had been offered a residency at Karolinska University Hospital, but that offer was withdrawn without explanation. Grinnemo had expected to receive an advisor position in cardiothoracic surgery, but that promotion also evaporated. In addition, the number of surgeries he was tapped to perform was reduced and he was relegated to doing the "less popular" standard heart surgeries that began late in the afternoon and evenings.

The grinding day-to-day pressure on the whistleblowers never let up. On December 19, 2014, Dr. Lockowandt informed all four that they had been on the verge of being fired, but that hospital attorneys changed their minds at the last minute. By then not only were their reputations in tatters, but they had invested an estimated 10,000 hours of labor investigating Macchiarini's misconduct, appealing to KI, and defending themselves against KI's harassment.

When interviewed for this article, Grinnemo said, "I have never had a single day of vacation from this situation. In addition to dealing with it, I've been doing surgery and taking care of patients. I've had trouble sleeping, and it has affected my family. I haven't been able to focus on my family, and I feel guilty toward my kids." Of all the whistleblowers, Grinnemo seems to have received the brunt of the backlash.

KI was finally pushed to further action by yet more negative coverage of the Macchiarini affair in the media. In January 2015, Swedish National Television aired an exposé covering the Macchiarini surgeries and the desperate plight of the patients. In response, the Swedish public demanded that KI make a course correction. On February 19, KI withdrew all of its threats of formal warnings to the whistleblowers.

As the press event began, KI called the heads of the whistleblowers' departments to tell them to make sure the four didn't attend.

However, progress was incremental. On April 16, KI's ethical committee, which had done its own investigation, acquitted Macchiarini of allegations of scientific misconduct. This is the same university ethical board that had reprimanded Grinnemo over his usage of data in the aortic valve grant application.

The whistleblowers maintain that throughout the summer of 2015, KI was still far more focused on covering up the Macchiarini affair than on getting to the bottom of it. On May 13, the professor from Uppsala submitted the results of his independent investigation, in which he concluded that seven out of seven published articles in which Macchiarini was the lead author entailed the fabrication of data.

KI ignored the report. In August 2015, KI's president announced that Macchiarini had been cleared of all charges of scientific misconduct and that, magically, ethical approvals existed for the patient from Iceland. Macchiarini got a reprimand for being "a little sloppy" in his published descriptions of his patients. Then KI, eager to placate the public and salvage its reputation, held a press conference to announce the presumed innocence of its star surgeon.

As the press event began, KI called the heads of the whistleblowers' departments to tell them to make sure the four didn't attend, according to Grinnemo.

"They seemed to think we would come crashing in to the press conference and make a scene. It's ridiculous, but that's what they thought," says Grinnemo.

Around this time, KI asked that the whistleblowers compile and forward all of their correspondence with the independent investigator on the grounds that they were suspected of manipulating his investigation. The accusation went nowhere; the whistleblowers had barely spoken with him.

Then came a request from KI's IT department for the whistleblowers to compile and submit all of their emails for the preceding year. They were simply told that "an anonymous person" had made the request.

Throughout 2015, KI continued to go after the whistleblowers aggressively. That August, they were so discouraged that they felt they would never obtain any additional grants from the Swedish Research Council or any other funding organizations, and that their academic careers were over. To add insult to injury, a Swedish newspaper published an article defending Macchiarini and concluding that he was not guilty of violating the Helsinki Declaration, a statute put into effect after World War II protecting all humans from unauthorized medical experimentation.

THE TIDE TURNS, BUT REDEMPTION IS ELUSIVE

Then in November, they received a request from a Swedish filmmaker to be interviewed about the Macchiarini affair. Not knowing what angle the film was expected to take, they each put in hours in front of the camera. They wouldn't know the results of their interviews until January 2016, when the three-part documentary, "The Experiments," aired on Swedish television. The film documented the tortuous death of a Russian woman and the suffering of other patients who had received Macchiarini's implants.

That same month, a devastating article on Paolo Macchiarini was published in the American magazine Vanity Fair. Titled "The Celebrity Surgeon Who Used Love, Money and the Pope to Scam an NBC News Producer," the article revealed Macchiarini as an even more prolific fabulist and liar than anyone had remotely suspected. Not only did he fabricate data for multiple scientific papers, he had also lied about everything from his alleged medical training and celebrity connections to his personal relationship status.

Ironically, the woman who ultimately dismantled Macchiarini was Benita Alexander, a former producer for NBC News who was at one point engaged to marry him in a lavish ceremony that Macchiarini promised would be officiated by Pope Francis. Except that he didn't know the Pope, and he was already married to one woman and living with another.

Her story of heartbreak infuriated the public. The full list of people who had believed Macchiarini's almost countless fabrications may never be known—a tribute to his considerable personal charisma. But after the "The Experiments" and the Vanity Fair article, the public had had enough of Paolo Macchiarini. They demanded that KI's president step down and that Macchiarini be fired.

TV producer Benita Alexander appeared as a guest on Dr. Oz's show on February 14th, 2018 to discuss Dr. Macchiarini's deception. "He railroaded my life," she said.

In February 2016, there was a cascade of resignations and firings at KI. First, president Anders Hamsten stepped down. Then several top KI officials, including the General Secretary of the Nobel Assembly, the Dean of Research, and an advisor to KI's president, were either fired or stepped down. On March 3, several members of the board were replaced. The whistleblowers received an award for coming forward by an organization called Transparency International, but instead of heaving a sigh of relief, they only felt a continued sense of foreboding.

"We all felt very vulnerable because we knew that KI would retaliate in some way," says Grinnemo. A fellow whistleblower, Dr. Corbascio, gave an interview on a prime time news program saying that KI was a corrupt institution and should apologize to the patients' families and even pay them for their suffering. After that, both he and another colleague came under intensified scrutiny at work. They say that their supervisors, who were deeply involved in collaborations with Macchiarini, watched everything they did, apparently looking for a reason to fire them.

Grinnemo and Simonson both left KI to work for Uppsala University. But the lasting effects of the scandal followed them there. They still couldn't obtain any grants for new research, and other scientists at KI and elsewhere were unwilling to collaborate with them for fear of their own work being "tainted" by association.

On March 23, 2016, Paolo Macchiarini was finally sacked by KI. Still, the whistleblowers couldn't claim victory.

"Our aim," says Grinnemo, "was not to get him sacked but to stop the grafts, and we knew he would continue to do them in other countries. The clinical trial aiming to recruit 100 or so patients hadn't been halted. We tried to warn the Russian authorities and the EU grant office, and wanted them to stop the grant to Macchiarini. There was no response, so at that time we didn't know if the clinical trial would go forward."

Still, there was reason to hope. News of Macchiarini's scientific fraud, not to mention his personal debacle with Benita Alexander, had made its way around scientific circles in Germany and Britain, where a new investigation began.

Eventually, the entire board at Karolinska was replaced. Under its new president, the institute issued a decree this past summer finding the now thoroughly disgraced Macchiarini guilty of scientific misconduct, and concluding that six of his research papers should be retracted.

But in a cruelly ironic twist, KI took the whistleblowers' own investigation and turned it against them. KI's report found Grinnemo also guilty of scientific misconduct for apparently falling short in the care of the Icelandic patient, even though his role in the case had been minimal. It was like a punch in the gut, because the judgment cast Grinnemo as equally blameworthy to Macchiarini. It also failed to recognize that he had long ago not only withdrawn his name from the offending paper, but lobbied for years to have it retracted.

"This sends the message that whistleblowers in research will be punished. That's a serious problem."

The KI report also established the new category of "blameworthy" to describe two of the whistleblowers for their roles as co-authors in some of the papers. The whistleblowers did not receive a chance to respond to the new accusations before a decision was made to publicly reprimand them.

That decision can't be appealed.

Simonson told Science Magazine, "This sends the message that whistleblowers in research will be punished. That's a serious problem."

These days, Macchiarini is lying low but still publishing his supposed stem cell research, most recently on baboons. A paper published in March of this year in the Journal of Biomedical Materials lists his affiliation as Kazan Federal University in Russia, but in April 2017, the university fired him. He's rumored to be living in Italy and couldn't be reached for this article. He was investigated for criminal activity in Sweden and the case was closed without charges, but Grinnemo says that another prosecutor is now considering whether to bring charges against him for "aggravated manslaughter."

At KI, only Karin Dahlman Wright, who was the Institute's acting president during several months of these events, responded to a request for comment, but she claimed a near-total unawareness of the whistleblowers' narrative. Other officials there declined to be interviewed.

KI's clinical trial that was aiming to recruit new patients for biologically engineered tracheas is no longer happening. The European Commission posted on their research portal that the trial ended on March 31, 2017, stating: "Grant Agreement terminated."

As for Grinnemo, Simonson, Corbascio and Fux, they are still fighting for their careers. Grinnemo is currently suing KI for a chance to defend himself against its accusations of scientific misconduct. He's also claiming damages for lost grant funding, thousands of hours spent defending himself, and harm to his reputation. Whether he will prevail in court remains to be seen.

"KI did a very good job of destroying our careers," says Simonson. "They didn't do anything else well, but they did a very thorough job of that."

Indigenous wisdom plus honeypot ants could provide new antibiotics

Indigenous people in Australia dig pits next to a honeypot colony. Scientists think the honey can be used to make new antimicrobial drugs.

For generations, the Indigenous Tjupan people of Australia enjoyed the sweet treat of honey made by honeypot ants. As a favorite pastime, entire families would go searching for the underground colonies, first spotting a worker ant and then tracing it to its home. The ants, which belong to the species called Camponotus inflatus, usually build their subterranean homes near the mulga trees, Acacia aneura. Having traced an ant to its tree, it would be the women who carefully dug a pit next to a colony, cautious not to destroy the entire structure. Once the ant chambers were exposed, the women would harvest a small amount to avoid devastating the colony’s stocks—and the family would share the treat.

The Tjupan people also knew that the honey had antimicrobial properties. “You could use it for a sore throat,” says Danny Ulrich, a member of the Tjupan nation. “You could also use it topically, on cuts and things like that.”

These hunts have become rarer, as many of the Tjupan people have moved away and, up until now, the exact antimicrobial properties of the ant honey remained unknown. But recently, scientists Andrew Dong and Kenya Fernandes from the University of Sydney, joined Ulrich, who runs the Honeypot Ants tours in Kalgoorlie, a city in Western Australia, on a honey-gathering expedition. Afterwards, they ran a series of experiments analyzing the honey’s antimicrobial activity—and confirmed that the Indigenous wisdom was true. The honey was effective against Staphylococcus aureus, a common pathogen responsible for sore throats, skin infections like boils and sores, and also sepsis, which can result in death. Moreover, the honey also worked against two species of fungi, Cryptococcus and Aspergillus, which can be pathogenic to humans, especially those with suppressed immune systems.

In the era of growing antibiotic resistance and the rising threat of pathogenic fungi, these findings may help scientists identify and make new antimicrobial compounds. “Natural products have been honed over thousands and millions of years by nature and evolution,” says Fernandes. “And some of them have complex and intricate properties that make them really important as potential new antibiotics. “

In an era of growing resistance to antibiotics and new threats of fungi infections, the latest findings about honeypot ants are helping scientists identify new antimicrobial drugs.

Danny Ulrich

Bee honey is also known for its antimicrobial properties, but bees produce it very differently than the ants. Bees collect nectar from flowers, which they regurgitate at the hive and pack into the hexagonal honeycombs they build for storage. As they do so, they also add into the mix an enzyme called glucose oxidase produced by their glands. The enzyme converts atmospheric oxygen into hydrogen peroxide, a reactive molecule that destroys bacteria and acts as a natural preservative. After the bees pack the honey into the honeycombs, they fan it with their wings to evaporate the water. Once a honeycomb is full, the bees put a beeswax cover on it, where it stays well-preserved thanks to the enzymatic action, until the bees need it.

Less is known about the chemistry of ants’ honey-making. Similarly to bees, they collect nectar. They also collect the sweet sap of the mulga tree. Additionally, they also “milk” the aphids—small sap-sucking insects that live on the tree. When ants tickle the aphids with their antennae, the latter release a sweet substance, which the former also transfer to their colonies. That’s where the honey management difference becomes really pronounced. The ants don’t build any kind of structures to store their honey. Instead, they store it in themselves.

The workers feed their harvest to their fellow ants called repletes, stuffing them up to the point that their swollen bellies outgrow the ants themselves, looking like amber-colored honeypots—hence the name. Because of their size, repletes don’t move, but hang down from the chamber’s ceiling, acting as living feedstocks. When food becomes scarce, they regurgitate their reserves to their colony’s brethren. It’s not clear whether the repletes die afterwards or can be restuffed again. “That's a good question,” Dong says. “After they've been stretched, they can't really return to exactly the same shape.”

These replete ants are the “treat” the Tjupan women dug for. Once they saw the round-belly ants inside the chambers, they would reach in carefully and get a few scoops of them. “You see a lot of honeypot ants just hanging on the roof of the little openings,” says Ulrich’s mother, Edie Ulrich. The women would share the ants with family members who would eat them one by one. “They're very delicate,” shares Edie Ulrich—you have to take them out carefully, so they don’t accidentally pop and become a wasted resource. “Because you’d lose all this precious honey.”

Dong stumbled upon the honeypot ants phenomenon because he was interested in Indigenous foods and went on Ulrich’s tour. He quickly became fascinated with the insects and their role in the Indigenous culture. “The honeypot ants are culturally revered by the Indigenous people,” he says. Eventually he decided to test out the honey’s medicinal qualities.

The researchers were surprised to see that even the smallest, eight percent concentration of honey was able to arrest the growth of S. aureus.

To do this, the two scientists first diluted the ant honey with water. “We used something called doubling dilutions, which means that we made 32 percent dilutions, and then we halve that to 16 percent and then we half that to eight percent,” explains Fernandes. The goal was to obtain as much results as possible with the meager honey they had. “We had very, very little of the honeypot ant honey so we wanted to maximize the spectrum of results we can get without wasting too much of the sample.”

After that, the researchers grew different microbes inside a nutrient rich broth. They added the broth to the different honey dilutions and incubated the mixes for a day or two at the temperature favorable to the germs’ growth. If the resulting solution turned turbid, it was a sign that the bugs proliferated. If it stayed clear, it meant that the honey destroyed them. The researchers were surprised to see that even the smallest, eight percent concentration of honey was able to arrest the growth of S. aureus. “It was really quite amazing,” Fernandes says. “Eight milliliters of honey in 92 milliliters of water is a really tiny amount of honey compared to the amount of water.”

Similar to bee honey, the ants’ honey exhibited some peroxide antimicrobial activity, researchers found, but given how little peroxide was in the solution, they think the honey also kills germs by a different mechanism. “When we measured, we found that [the solution] did have some hydrogen peroxide, but it didn't have as much of it as we would expect based on how active it was,” Fernandes says. “Whether this hydrogen peroxide also comes from glucose oxidase or whether it's produced by another source, we don't really know,” she adds. The research team does have some hypotheses about the identity of this other germ-killing agent. “We think it is most likely some kind of antimicrobial peptide that is actually coming from the ant itself.”

The honey also has a very strong activity against the two types of fungi, Cryptococcus and Aspergillus. Both fungi are associated with trees and decaying leaves, as well as in the soils where ants live, so the insects likely have evolved some natural defense compounds, which end up inside the honey.

It wouldn’t be the first time when modern medicines take their origin from the natural world or from the indigenous people’s knowledge. The bark of the cinchona tree native to South America contains quinine, a substance that treats malaria. The Indigenous people of the Andes used the bark to quell fever and chills for generations, and when Europeans began to fall ill with malaria in the Amazon rainforest, they learned to use that medicine from the Andean people.

The wonder drug aspirin similarly takes its origin from a bark of a tree—in this case a willow.

Even some anticancer compounds originated from nature. A chemotherapy drug called Paclitaxel, was originally extracted from the Pacific yew trees, Taxus brevifolia. The samples of the Pacific yew bark were first collected in 1962 by researchers from the United States Department of Agriculture who were looking for natural compounds that might have anti-tumor activity. In December 1992, the FDA approved Paclitaxel (brand name Taxol) for the treatment of ovarian cancer and two years later for breast cancer.

In the era when the world is struggling to find new medicines fast enough to subvert a fungal or bacterial pandemic, these discoveries can pave the way to new therapeutics. “I think it's really important to listen to indigenous cultures and to take their knowledge because they have been using these sources for a really, really long time,” Fernandes says. Now we know it works, so science can elucidate the molecular mechanisms behind it, she adds. “And maybe it can even provide a lead for us to develop some kind of new treatments in the future.”

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Blood Test Can Detect Lymphoma Cells Before a Tumor Grows Back

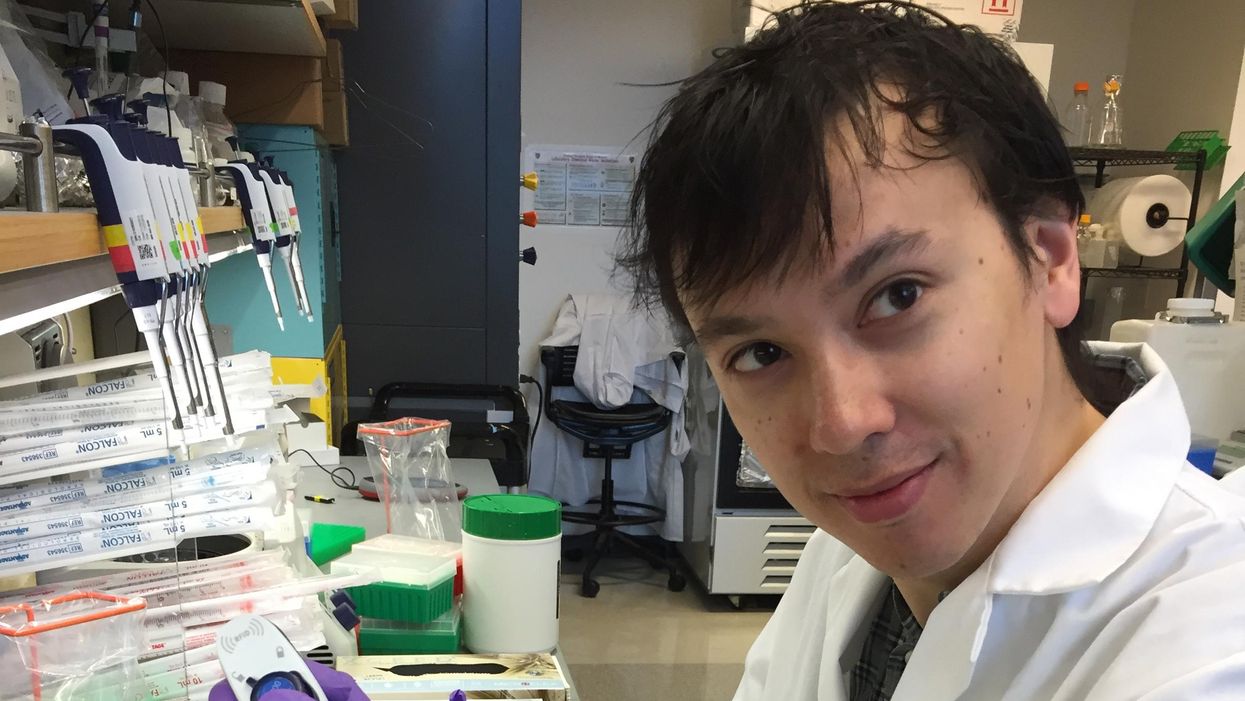

David Kurtz making DNA sequencing libraries in his lab.

When David M. Kurtz was doing his clinical fellowship at Stanford University Medical Center in 2009, specializing in lymphoma treatments, he found himself grappling with a question no one could answer. A typical regimen for these blood cancers prescribed six cycles of chemotherapy, but no one knew why. "The number seemed to be drawn out of a hat," Kurtz says. Some patients felt much better after just two doses, but had to endure the toxic effects of the entire course. For some elderly patients, the side effects of chemo are so harsh, they alone can kill. Others appeared to be cancer-free on the CT scans after the requisite six but then succumbed to it months later.

"Anecdotally, one patient decided to stop therapy after one dose because he felt it was so toxic that he opted for hospice instead," says Kurtz, now an oncologist at the center. "Five years down the road, he was alive and well. For him, just one dose was enough." Others would return for their one-year check up and find that their tumors grew back. Kurtz felt that while CT scans and MRIs were powerful tools, they weren't perfect ones. They couldn't tell him if there were any cancer cells left, stealthily waiting to germinate again. The scans only showed the tumor once it was back.

Blood cancers claim about 68,000 people a year, with a new diagnosis made about every three minutes, according to the Leukemia Research Foundation. For patients with B-cell lymphoma, which Kurtz focuses on, the survival chances are better than for some others. About 60 percent are cured, but the remaining 40 percent will relapse—possibly because they will have a negative CT scan, but still harbor malignant cells. "You can't see this on imaging," says Michael Green, who also treats blood cancers at University of Texas MD Anderson Medical Center.

The new blood test is sensitive enough to spot one cancerous perpetrator amongst one million other DNA molecules.

Kurtz wanted a better diagnostic tool, so he started working on a blood test that could capture the circulating tumor DNA or ctDNA. For that, he needed to identify the specific mutations typical for B-cell lymphomas. Working together with another fellow PhD student Jake Chabon, Kurtz finally zeroed-in on the tumor's genetic "appearance" in 2017—a pair of specific mutations sitting in close proximity to each other—a rare and telling sign. The human genome contains about 3 billion base pairs of nucleotides—molecules that compose genes—and in case of the B-cell lymphoma cells these two mutations were only a few base pairs apart. "That was the moment when the light bulb went on," Kurtz says.

The duo formed a company named Foresight Diagnostics, focusing on taking the blood test to the clinic. But knowing the tumor's mutational signature was only half the process. The other was fishing the tumor's DNA out of patients' bloodstream that contains millions of other DNA molecules, explains Chabon, now Foresight's CEO. It would be like looking for an escaped criminal in a large crowd. Kurtz and Chabon solved the problem by taking the tumor's "mug shot" first. Doctors would take the biopsy pre-treatment and sequence the tumor, as if taking the criminal's photo. After treatments, they would match the "mug shot" to all DNA molecules derived from the patient's blood sample to see if any molecular criminals managed to escape the chemo.

Foresight isn't the only company working on blood-based tumor detection tests, which are dubbed liquid biopsies—other companies such as Natera or ArcherDx developed their own. But in a recent study, the Foresight team showed that their method is significantly more sensitive in "fishing out" the cancer molecules than existing tests. Chabon says that this test can detect circulating tumor DNA in concentrations that are nearly 100 times lower than other methods. Put another way, it's sensitive enough to spot one cancerous perpetrator amongst one million other DNA molecules.

They also aim to extend their test to detect other malignancies such as lung, breast or colorectal cancers.

"It increases the sensitivity of detection and really catches most patients who are going to progress," says Green, the University of Texas oncologist who wasn't involved in the study, but is familiar with the method. It would also allow monitoring patients during treatment and making better-informed decisions about which therapy regimens would be most effective. "It's a minimally invasive test," Green says, and "it gives you a very high confidence about what's going on."

Having shown that the test works well, Kurtz and Chabon are planning a new trial in which oncologists would rely on their method to decide when to stop or continue chemo. They also aim to extend their test to detect other malignancies such as lung, breast or colorectal cancers. The latest genome sequencing technologies have sequenced and catalogued over 2,500 different tumor specimens and the Foresight team is analyzing this data, says Chabon, which gives the team the opportunity to create more molecular "mug shots."

The team hopes that that their blood cancer test will become available to patients within about five years, making doctors' job easier, and not only at the biological level. "When I tell patients, "good news, your cancer is in remission', they ask me, 'does it mean I'm cured?'" Kurtz says. "Right now I can't answer this question because I don't know—but I would like to." His company's test, he hopes, will enable him to reply with certainty. He'd very much like to have the power of that foresight.

This article is republished from our archives to coincide with Blood Cancer Awareness Month, which highlights progress in cancer diagnostics and treatment.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.