A Surprising Breakthrough Will Allow Tiny Implants to Fix—and Even Upgrade—Your Body

The medical implants of the future will prompt lively discussion around the boundaries between treatment and enhancement.

Imagine it's the year 2040 and you're due for your regular health checkup. Time to schedule your next colonoscopy, Pap smear if you're a woman, and prostate screen if you're a man.

"The evolution of the biological ion transistor technology is a game changer."

But wait, you no longer need any of those, since you recently got one of the new biomed implants – a device that integrates seamlessly with body tissues, because of a watershed breakthrough that happened in the early 2020s. It's an improved biological transistor driven by electrically charged particles that move in and out of your own cells. Like insulin pumps and cardiac pacemakers, the medical implants of the future will go where they are needed, on or inside the body.

But unlike current implants, biological transistors will have a remarkable range of applications. Currently small enough to fit between a patient's hair follicles, the devices could one day enable correction of problems ranging from damaged heart muscle to failing retinas to deficiencies of hormones and enzymes.

Their usefulness raises the prospect of overcorrection to the point of human enhancement, as in the bionic parts that were imagined on the ABC television series The Six Million Dollar Man, which aired in the 1970s.

"The evolution of the biological ion transistor technology is a game changer," says Zoltan Istvan, who ran as a U.S. Presidential candidate in 2016 for the Transhumanist Party and later ran for California governor. Istvan envisions humans becoming faster, stronger, and increasingly more capable by way of technological innovations, especially in the biotechnology realm. "It's a big step forward on how we can improve and upgrade the human body."

How It Works

The new transistors are more like the soft, organic machines that biology has evolved than like traditional transistors built of semiconductors and metal, according to electric engineering expert Dion Khodagholy, one of the leaders of the team at Columbia University that developed the technology.

The key to the advance, notes Khodagholy, is that the transistors will interface seamlessly with tissue, because the electricity will be of the biological type -- transmitted via the flow of ions through liquid, rather than electrons through metal. This will boost the sensitivity of detection and decoding of biological change.

Naturally, such a paradigm change in the world of medical devices raises potential societal and ethical dilemmas.

Known as an ion-gated transistor (IGT), the new class of technology effectively melds electronics with molecules of human skin. That's the current prototype, but ultimately, biological devices will be able to go anywhere in the body. "IGT-based devices hold great promise for development of fully implantable bioelectronic devices that can address key clinical issues for patients with neuropsychiatric disease," says Khodagholy, based on the expectation that future devices could fuse with, measure, and modulate cells of the human nervous system.

Ethical Implications

Naturally, such a paradigm change in the world of medical devices raises potential societal and ethical dilemmas, starting with who receives the new technology and who pays for it. But, according clinical ethicist and health care attorney David Hoffman, we can gain insight from past experience, such as how society reacted to the invention of kidney dialysis in the mid 20th century.

"Kidney dialysis has been federally funded for all these decades, largely because the who-gets-the-technology question was an issue when the technology entered clinical medicine," says Hoffman, who teaches bioethics at Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons as well as at the law school and medical school of Yeshiva University. Just as dialysis became a necessity for many patients, he suggests that the emerging bio-transistors may also become critical life-sustaining devices, prompting discussions about federal coverage.

But unlike dialysis, biological transistors could allow some users to become "better than well," making it more similar to medication for ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder): People who don't require it can still use it to improve their baseline normal functioning. This raises the classic question: Should society draw a line between treatment and enhancement? And who gets to decide the answer?

If it's strictly a medical use of the technology, should everyone who needs it get to use it, regardless of ability to pay, relying on federal or private insurance coverage? On the other hand, if it's used voluntarily for enhancement, should that option also be available to everyone -- but at an upfront cost?

From a transhumanist viewpoint, getting wrapped up with concerns about the evolution of devices from therapy to enhancement is not worth the trouble.

It seems safe to say that some lively debates and growing pains are on the horizon.

"Even if [the biological ion transistor] is developed only for medical devices that compensate for losses and deficiencies similar to that of a cardiac pacemaker, it will be hard to stop its eventual evolution from compensation to enhancement," says Istvan. "If you use it in a bionic eye to restore vision to the blind, how do you draw the line between replacement of normal function and provision of enhanced function? Do you pass a law placing limits on visual capabilities of a synthetic eye? Transhumanists would oppose such laws, and any restrictions in one country or another would allow another country to gain an advantage by creating their own real-life super human cyborg citizens."

In the same breath though, Istvan admits that biotechnology on a bionic scale is bound to complicate a range of international phenomena, from economic growth and military confrontations to sporting events like the Olympic Games.

The technology is already here, and it's just a matter of time before we see clinically viable, implantable devices. As for how society will react, it seems safe to say that some lively debates and growing pains are on the horizon.

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

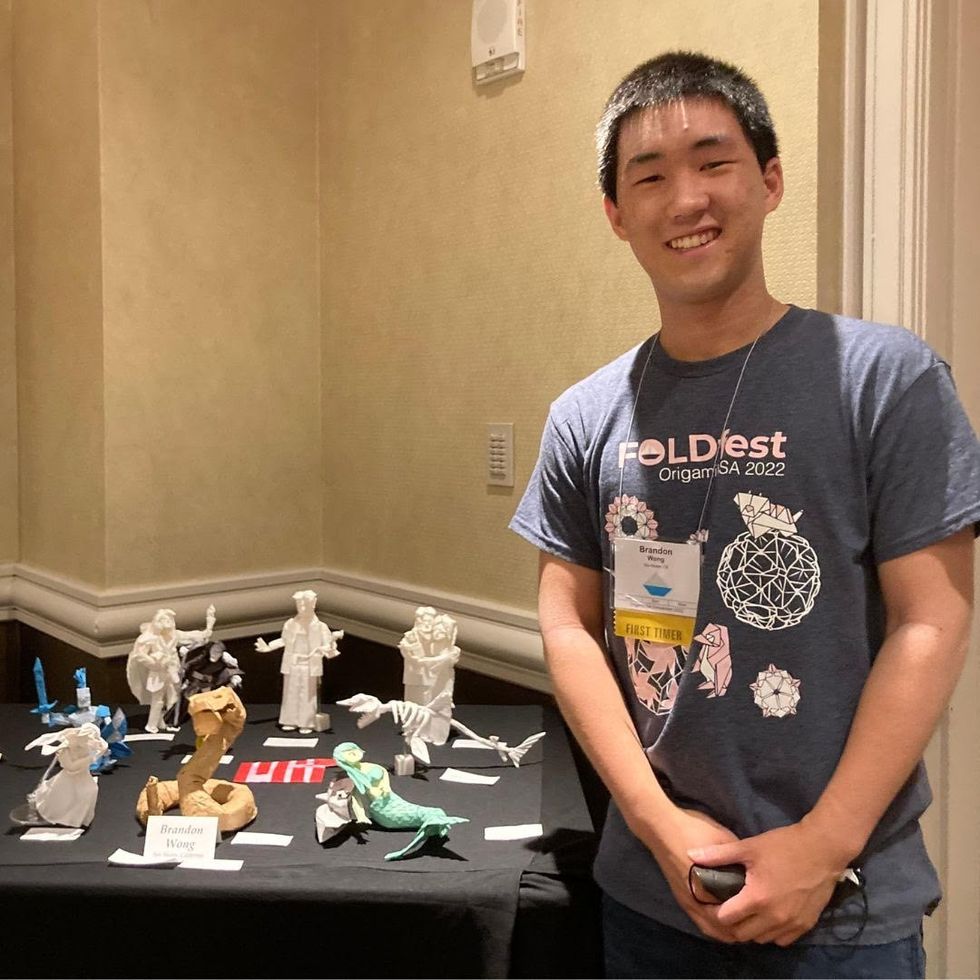

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”