A Team of Israeli Students Just Created Honey Without Bees

The bee-free honey on the left, and the Israeli team that won the iGEM competition.

Can you make honey without honeybees? According to 12 Israeli students who took home a gold medal in the iGEM (International Genetically Engineered Machine) competition with their synthetic honey project, the answer is yes, you can.

The honey industry faces serious environmental challenges, like the mysterious Colony Collapse Disorder.

For the past year, the team from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology has been working on creating sustainable, artificial honey—no bees required. Why? As the team explains in a video on the project's website, "Studies have shown the amazing nutritional values of honey. However, the honey industry harms the environment, and particularly the bees. That's why vegans don't use honey and why our honey will be a great replacement."

Indeed, honey has long been a controversial product in the vegan community. Some say it's stealing an animal's food source (though bees make more honey than they can possibly use). Some avoid eating honey because it is an animal product and bees' natural habitats are disturbed by humans harvesting it. Others feel that because bees aren't directly killed or harmed in the production of honey, it's not actually unethical to eat.

However, there's no doubt that the honey industry faces some serious environmental challenges. Colony Collapse Disorder, a mysterious phenomenon in which worker bees in colonies disappear in large numbers without any real explanation, came to international attention in 2006. Several explanations from poisonous pesticides to immune-suppressing stress to new or emerging diseases have been posited, but no definitive cause has been found.

There's also the problem of human-managed honey farms having a negative impact on the natural honeybee population.

So how can honey be made without honeybees? It's all about bacteria and enzymes.

The way bees make honey is by collecting nectar from flowers, transporting it in their "honey stomach" (which is separate from their food stomach), and bringing it back to the hive, where it gets transferred from bee mouth to bee mouth. That transferal process reduces the moisture content from about 70 percent to 20 percent, and honey is formed.

The product is still currently under development.

The Technion students created a model of a synthetic honey stomach metabolic pathway, in which the bacterium Bacillus subtilis "learns" to produce honey. "The bacteria can independently control the production of enzymes, eventually achieving a product with the same sugar profile as real honey, and the same health benefits," the team explains. Bacillus subtilis, which is found in soil, vegetation, and our own gastrointestinal tracts, has a natural ability to produce catalase, one of the enzymes needed for honey production. The product is still currently under development.

Whether this project results in a real-world jar of honey we'll be able to buy at the grocery store remains to be seen, but imagine how happy the bees—and vegans—would be if it did.

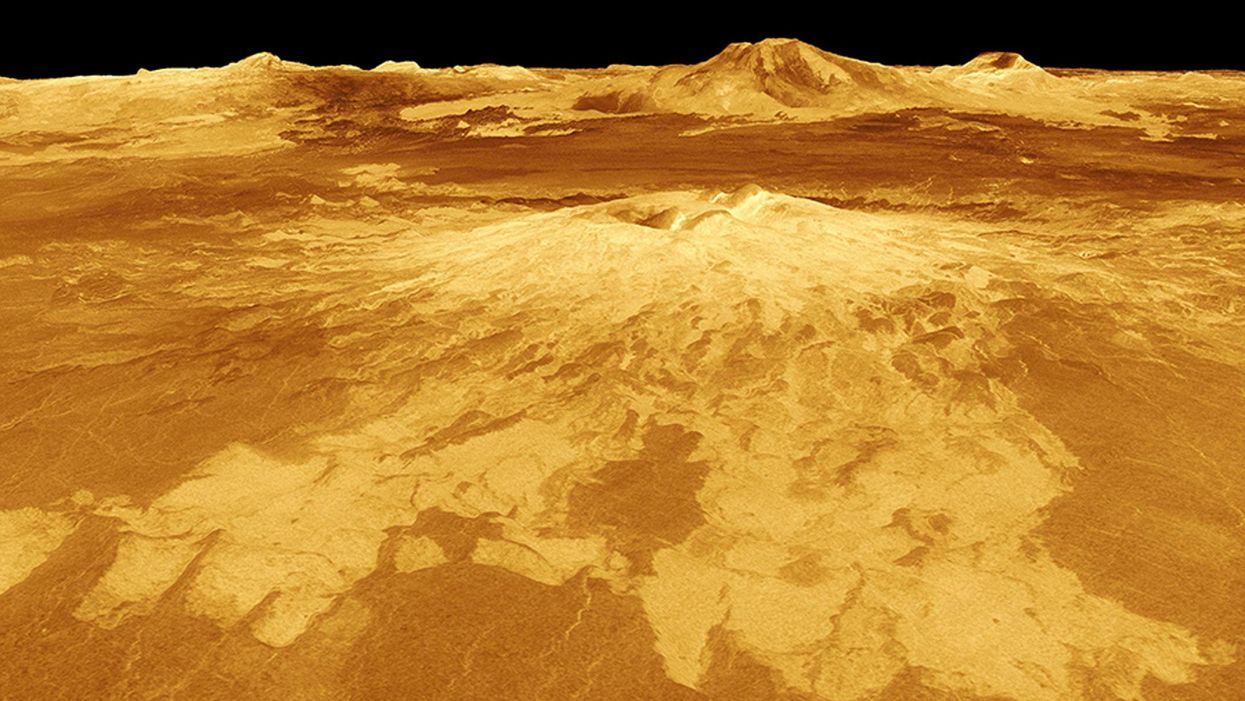

New Podcast: The Lead Scientist for the NASA Mission to Venus

The volcano Sapas Mons is displayed in the center of this computer-generated three-dimensional perspective view of the surface of Venus.

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading medical and scientific experts about the latest developments and the big ethical and societal questions they raise. This monthly podcast is hosted by journalist Kira Peikoff, founding editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

This month, our guest is JPL's Dr. Suzanne Smrekar, who will be pushing the boundaries of knowledge about the planet Venus during the upcoming VERITAS mission set to launch in 2028. Why did Earth's twin planet develop so differently than our own? Could Venus ever have hosted life? What is the bigger purpose for humanity in studying the solar system -- is it purely scientific, or is it also a matter of art and philosophy? Hear Dr. Smrekar discuss all this and more on the latest episode.

Watch the 30-Second Trailer:

Listen to the Episode:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

New Blood Test Can Detect Lymphoma Cells Before a Tumor Grows Back

David Kurtz making DNA sequencing libraries in his lab.

When David M. Kurtz was doing his clinical fellowship at Stanford University Medical Center in 2009, specializing in lymphoma treatments, he found himself grappling with a question no one could answer. A typical regimen for these blood cancers prescribed six cycles of chemotherapy, but no one knew why. "The number seemed to be drawn out of a hat," Kurtz says. Some patients felt much better after just two doses, but had to endure the toxic effects of the entire course. For some elderly patients, the side effects of chemo are so harsh, they alone can kill. Others appeared to be cancer-free on the CT scans after the requisite six but then succumbed to it months later.

"Anecdotally, one patient decided to stop therapy after one dose because he felt it was so toxic that he opted for hospice instead," says Kurtz, now an oncologist at the center. "Five years down the road, he was alive and well. For him, just one dose was enough." Others would return for their one-year check up and find that their tumors grew back. Kurtz felt that while CT scans and MRIs were powerful tools, they weren't perfect ones. They couldn't tell him if there were any cancer cells left, stealthily waiting to germinate again. The scans only showed the tumor once it was back.

Blood cancers claim about 68,000 people a year, with a new diagnosis made about every three minutes, according to the Leukemia Research Foundation. For patients with B-cell lymphoma, which Kurtz focuses on, the survival chances are better than for some others. About 60 percent are cured, but the remaining 40 percent will relapse—possibly because they will have a negative CT scan, but still harbor malignant cells. "You can't see this on imaging," says Michael Green, who also treats blood cancers at University of Texas MD Anderson Medical Center.

The new blood test is sensitive enough to spot one cancerous perpetrator amongst one million other DNA molecules.

Kurtz wanted a better diagnostic tool, so he started working on a blood test that could capture the circulating tumor DNA or ctDNA. For that, he needed to identify the specific mutations typical for B-cell lymphomas. Working together with another fellow PhD student Jake Chabon, Kurtz finally zeroed-in on the tumor's genetic "appearance" in 2017—a pair of specific mutations sitting in close proximity to each other—a rare and telling sign. The human genome contains about 3 billion base pairs of nucleotides—molecules that compose genes—and in case of the B-cell lymphoma cells these two mutations were only a few base pairs apart. "That was the moment when the light bulb went on," Kurtz says.

The duo formed a company named Foresight Diagnostics, focusing on taking the blood test to the clinic. But knowing the tumor's mutational signature was only half the process. The other was fishing the tumor's DNA out of patients' bloodstream that contains millions of other DNA molecules, explains Chabon, now Foresight's CEO. It would be like looking for an escaped criminal in a large crowd. Kurtz and Chabon solved the problem by taking the tumor's "mug shot" first. Doctors would take the biopsy pre-treatment and sequence the tumor, as if taking the criminal's photo. After treatments, they would match the "mug shot" to all DNA molecules derived from the patient's blood sample to see if any molecular criminals managed to escape the chemo.

Foresight isn't the only company working on blood-based tumor detection tests, which are dubbed liquid biopsies—other companies such as Natera or ArcherDx developed their own. But in a recent study, the Foresight team showed that their method is significantly more sensitive in "fishing out" the cancer molecules than existing tests. Chabon says that this test can detect circulating tumor DNA in concentrations that are nearly 100 times lower than other methods. Put another way, it's sensitive enough to spot one cancerous perpetrator amongst one million other DNA molecules.

"It increases the sensitivity of detection and really catches most patients who are going to progress," says Green, the University of Texas oncologist who wasn't involved in the study, but is familiar with the method. It would also allow monitoring patients during treatment and making better-informed decisions about which therapy regimens would be most effective. "It's a minimally invasive test," Green says, and "it gives you a very high confidence about what's going on."

Having shown that the test works well, Kurtz and Chabon are planning a new trial in which oncologists would rely on their method to decide when to stop or continue chemo. They also aim to extend their test to detect other malignancies such as lung, breast or colorectal cancers. The latest genome sequencing technologies have sequenced and catalogued over 2,500 different tumor specimens and the Foresight team is analyzing this data, says Chabon, which gives the team the opportunity to create more molecular "mug shots."

The team hopes that that their blood cancer test will become available to patients within about five years, making doctors' job easier, and not only at the biological level. "When I tell patients, "good news, your cancer is in remission', they ask me, 'does it mean I'm cured?'" Kurtz says. "Right now I can't answer this question because I don't know—but I would like to." His company's test, he hopes, will enable him to reply with certainty. He'd very much like to have the power of that foresight.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.