A Team of Israeli Students Just Created Honey Without Bees

The bee-free honey on the left, and the Israeli team that won the iGEM competition.

Can you make honey without honeybees? According to 12 Israeli students who took home a gold medal in the iGEM (International Genetically Engineered Machine) competition with their synthetic honey project, the answer is yes, you can.

The honey industry faces serious environmental challenges, like the mysterious Colony Collapse Disorder.

For the past year, the team from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology has been working on creating sustainable, artificial honey—no bees required. Why? As the team explains in a video on the project's website, "Studies have shown the amazing nutritional values of honey. However, the honey industry harms the environment, and particularly the bees. That's why vegans don't use honey and why our honey will be a great replacement."

Indeed, honey has long been a controversial product in the vegan community. Some say it's stealing an animal's food source (though bees make more honey than they can possibly use). Some avoid eating honey because it is an animal product and bees' natural habitats are disturbed by humans harvesting it. Others feel that because bees aren't directly killed or harmed in the production of honey, it's not actually unethical to eat.

However, there's no doubt that the honey industry faces some serious environmental challenges. Colony Collapse Disorder, a mysterious phenomenon in which worker bees in colonies disappear in large numbers without any real explanation, came to international attention in 2006. Several explanations from poisonous pesticides to immune-suppressing stress to new or emerging diseases have been posited, but no definitive cause has been found.

There's also the problem of human-managed honey farms having a negative impact on the natural honeybee population.

So how can honey be made without honeybees? It's all about bacteria and enzymes.

The way bees make honey is by collecting nectar from flowers, transporting it in their "honey stomach" (which is separate from their food stomach), and bringing it back to the hive, where it gets transferred from bee mouth to bee mouth. That transferal process reduces the moisture content from about 70 percent to 20 percent, and honey is formed.

The product is still currently under development.

The Technion students created a model of a synthetic honey stomach metabolic pathway, in which the bacterium Bacillus subtilis "learns" to produce honey. "The bacteria can independently control the production of enzymes, eventually achieving a product with the same sugar profile as real honey, and the same health benefits," the team explains. Bacillus subtilis, which is found in soil, vegetation, and our own gastrointestinal tracts, has a natural ability to produce catalase, one of the enzymes needed for honey production. The product is still currently under development.

Whether this project results in a real-world jar of honey we'll be able to buy at the grocery store remains to be seen, but imagine how happy the bees—and vegans—would be if it did.

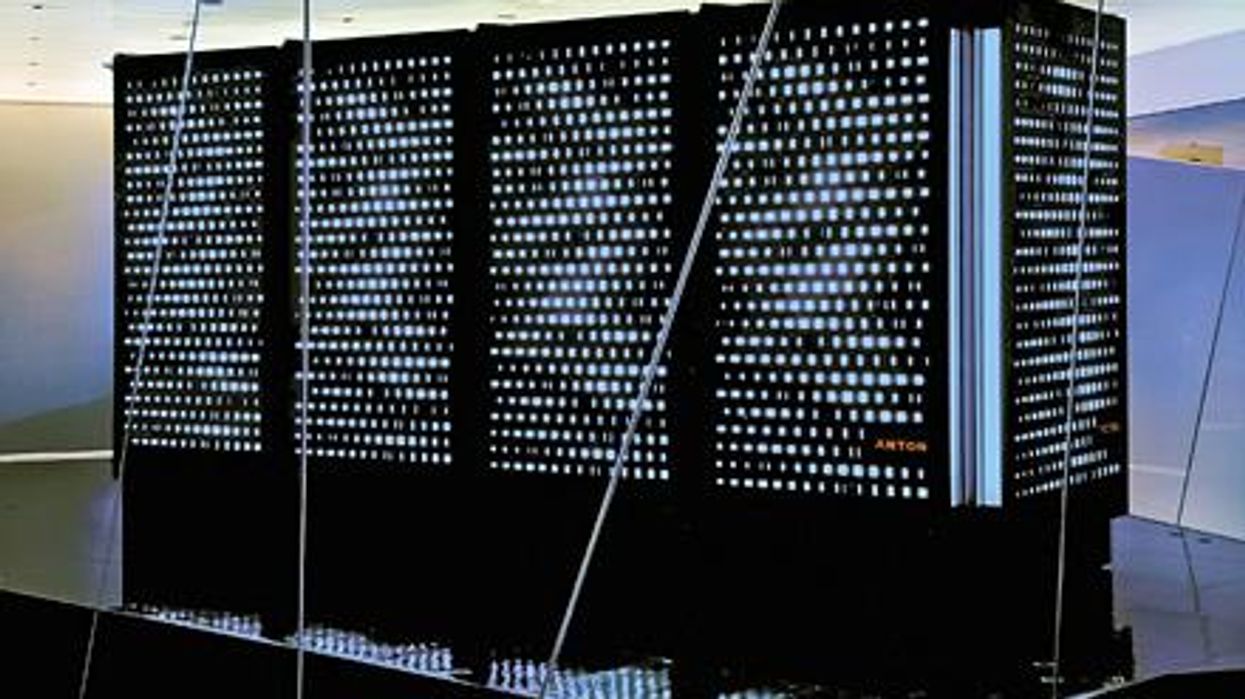

Did Anton the AI find a new treatment for a deadly cancer?

Researchers used a supercomputer to learn about the subtle movement of a cancer-causing molecule, and then they found the precise drug that can recognize that motion.

Bile duct cancer is a rare and aggressive form of cancer that is often difficult to diagnose. Patients with advanced forms of the disease have an average life expectancy of less than two years.

Many patients who get cancer in their bile ducts – the tubes that carry digestive fluid from the liver to the small intestine – have mutations in the protein FGFR2, which leads cells to grow uncontrollably. One treatment option is chemotherapy, but it’s toxic to both cancer cells and healthy cells, failing to distinguish between the two. Increasingly, cancer researchers are focusing on biomarker directed therapy, or making drugs that target a particular molecule that causes the disease – FGFR2, in the case of bile duct cancer.

A problem is that in targeting FGFR2, these drugs inadvertently inhibit the FGFR1 protein, which looks almost identical. This causes elevated phosphate levels, which is a sign of kidney damage, so doses are often limited to prevent complications.

In recent years, though, a company called Relay has taken a unique approach to picking out FGFR2, using a powerful supercomputer to simulate how proteins move and change shape. The team, leveraging this AI capability, discovered that FGFR2 and FGFR1 move differently, which enabled them to create a more precise drug.

Preliminary studies have shown robust activity of this drug, called RLY-4008, in FGFR2 altered tumors, especially in bile duct cancer. The drug did not inhibit FGFR1 or cause significant side effects. “RLY-4008 is a prime example of a precision oncology therapeutic with its highly selective and potent targeting of FGFR2 genetic alterations and resistance mutations,” says Lipika Goyal, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is a principal investigator of Relay’s phase 1-2 clinical trial.

Boosts from AI and a billionaire

Traditional drug design has been very much a case of trial and error, as scientists investigate many molecules to see which ones bind to the intended target and bind less to other targets.

“It’s being done almost blindly, without really being guided by structure, so it fails very often,” says Olivier Elemento, associate director of the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Cornell. “The issue is that they are not sampling enough molecules to cover some of the chemical space that would be specific to the target of interest and not specific to others.”

Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

Some scientists have tried to use X-rays of crystallized proteins to look at the structure of proteins and design better drugs. But they have failed to account for an important factor: proteins are moving and constantly folding into different shapes.

David Shaw, a hedge fund billionaire, wanted to help improve drug discovery and understood that a key obstacle was that computer models of molecular dynamics were limited; they simulated motion for less than 10 millionths of a second.

In 2001, Shaw set up his own research facility, D.E. Shaw Research, to create a supercomputer that would be specifically designed to simulate protein motion. Seven years later, he succeeded in firing up a supercomputer that can now conduct high speed simulations roughly 100 times faster than others. Called Anton, it has special computer chips to enable this speed, and its software is powered by AI to conduct many simulations.

After creating the supercomputer, Shaw teamed up with leading scientists who were interested in molecular motion, and they founded Relay Therapeutics.

Elemento believes that Relay’s approach is highly beneficial in designing a better drug for bile duct cancer. “Relay Therapeutics has a cutting-edge approach for molecular dynamics that I don’t believe any other companies have, at least not as advanced.” Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

How it works

Relay used both experimental and computational approaches to design RLY-4008. The team started out by taking X-rays of crystallized versions of both their intended target, FGFR2, and the almost identical FGFR1. This enabled them to get a 3D snapshot of each of their structures. They then fed the X-rays into the Anton supercomputer to simulate how the proteins were likely to move.

Anton’s simulations showed that the FGFR1 protein had a flap that moved more frequently than FGFR2. Based on this distinct motion, the team tried to design a compound that would recognize this flap shifting around and bind to FGFR2 while steering away from its more active lookalike.

For that, they went back Anton, using the supercomputer to simulate the behavior of thousands of potential molecules for over a year, looking at what made a particular molecule selective to the target versus another molecule that wasn’t. These insights led them to determine the best compounds to make and test in the lab and, ultimately, they found that RLY-4008 was the most effective.

Promising results so far

Relay began phase 1-2 trials in 2020 and will continue until 2024. Preliminary results showed that, in the 17 patients taking a 70 mg dose of RLY-4008, the drug worked to shrink tumors in 88 percent of patients. This was a significant increase compared to other FGFR inhibitors. For instance, Futibatinib, which recently got FDA approval, had a response rate of only 42 percent.

Across all dose levels, RLY-4008 shrank tumors by 63 percent in 38 patients. In more good news, the drug didn’t elevate their phosphate levels, which suggests that it could be taken without increasing patients’ risk for kidney disease.

“Objectively, this is pretty remarkable,” says Elemento. “In a small patient study, you have a molecule that is able to shrink tumors in such a high fraction of patients. It is unusual to see such good results in a phase 1-2 trial.”

A simulated future

The research team is continuing to use molecular dynamic simulations to develop other new drug, such as one that is being studied in patients with solid tumors and breast cancer.

As for their bile duct cancer drug, RLY-4008, Relay plans by 2024 to have tested it in around 440 patients. “The mature results of the phase 1-2 trial are highly anticipated,” says Goyal, the principal investigator of the trial.

Sameek Roychowdhury, an oncologist and associate professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University, highlights the need for caution. “This has early signs of benefit, but we will look forward to seeing longer term results for benefit and side effect profiles. We need to think a few more steps ahead - these treatments are like the ’Whack-a-Mole game’ where cancer finds a way to become resistant to each subsequent drug.”

“I think the issue is going to be how durable are the responses to the drug and what are the mechanisms of resistance,” says Raymond Wadlow, an oncologist at the Inova Medical Group who specializes in gastrointestinal and haematological cancer. “But the results look promising. It is a much more selective inhibitor of the FGFR protein and less toxic. It’s been an exciting development.”

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help