Abortions Before Fetal Viability Are Legal: Might Science and the Change on the Supreme Court Undermine That?

The United States Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

Viability—the potential for a fetus to survive outside the womb—is a core dividing line in American law. For almost 50 years, the Supreme Court of the United States has struck down laws that ban all or most abortions, ruling that women's constitutional rights include choosing to end pregnancies before the point of viability. Once viability is reached, however, states have a "compelling interest" in protecting fetal life. At that point, states can choose to ban or significantly restrict later-term abortions provided states allow an exception to preserve the life or health of the mother.

This distinction between a fetus that could survive outside its mother's body, albeit with significant medical intervention, and one that could not, is at the heart of the court's landmark 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade. The framework of viability remains central to the country's abortion law today, even as some states have passed laws in the name of protecting women's health that significantly undermine Roe. Over the last 30 years, the Supreme Court has upheld these laws, which have the effect of restricting pre-viability abortion access, imposing mandatory waiting periods, requiring parental consent for minors, and placing restrictions on abortion providers.

Viability has always been a slippery notion on which to pin legal rights.

Today, the Guttmacher Institute reports that more than half of American women live in states whose laws are considered hostile to abortion, largely as a result of these intrusions on pre-viability abortion access. Nevertheless, the viability framework stands: while states can pass pre-viability abortion restrictions that (ostensibly) protect the health of the woman or that strike some kind a balance between women's rights and fetal life, it is only after viability that they can completely favor fetal life over the rights of the woman (with limited exceptions when the woman's life is threatened). As a result, judges have struck down certain states' so-called heartbeat laws, which tried to prohibit abortions after detection of a fetal heartbeat (as early as six weeks of pregnancy). Bans on abortion after 12 or 15 weeks' gestation have also been reversed.

Now, with a new Supreme Court Justice expected to be hostile to abortion rights, advances in the care of preterm babies and ongoing research on artificial wombs suggest that the point of viability is already sooner than many assume and could soon be moved radically earlier in gestation, potentially providing a legal basis for earlier and earlier abortion bans.

Viability has always been a slippery notion on which to pin legal rights. It represents an inherently variable and medically shifting moment in the pregnancy timeline that the Roe majority opinion declined to firmly define, noting instead that "[v]iability is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks." Even in 1977, this definition was an optimistic generalization. Every baby is different, and while some 28-week infants born the year Roe was decided did indeed live into adulthood, most died at or shortly after birth. The prognosis for infants born at 24 weeks was much worse.

Today, a baby born at 28 weeks' gestation can be expected to do much better, largely due to the development of surfactant treatment in the early 1990s to help ease the air into babies' lungs. Now, the majority of 24-week-old babies can survive, and several very premature babies, born just shy of 22 weeks' gestation, have lived into childhood. All this variability raises the question: Should the law take a very optimistic, if largely unrealistic, approach to defining viability and place it at 22 weeks, even though the overall survival rate for those preemies remains less than 10% today? Or should the law recognize that keeping a premature infant alive requires specialist care, meaning that actual viability differs not just pregnancy-to-pregnancy but also by healthcare facility and from country to country? A 24-week premature infant born in a rural area or in a developing nation may not be viable as a practical matter, while one born in a major U.S. city with access to state-of-the-art care has a greater than 70% chance of survival. Just as some extremely premature newborns survive, some full-term babies die before, during, or soon after birth, regardless of whether they have access to advanced medical care.

To be accurate, viability should be understood as pregnancy-specific and should take into account the healthcare resources available to that woman. But state laws can't capture this degree of variability by including gestation limits in their abortion laws. Instead, many draw a somewhat arbitrary line at 22, 24, or 28 weeks' gestation, regardless of the particulars of the pregnancy or the medical resources available in that state.

As variable and resource-dependent as viability is today, science may soon move that point even earlier. Ectogenesis is a term coined in 1923 for the growth of an organism outside the body. Long considered science fiction, this technology has made several key advances in the past few years, with scientists announcing in 2017 that they had successfully gestated premature lamb fetuses in an artificial womb for four weeks. Currently in development for use in human fetuses between 22 and 23 weeks' gestation, this technology will almost certainly seek to push viability earlier in pregnancy.

Ectogenesis and other improvements in managing preterm birth deserve to be celebrated, offering new hope to the parents of very premature infants. But in the U.S., and in other nations whose abortion laws are fixed to viability, these same advances also pose a threat to abortion access. Abortion opponents have long sought to move the cutoff for legal abortions, and it is not hard to imagine a state prohibiting all abortions after 18 or 20 weeks by arguing that medical advances render this stage "the new viability," regardless of whether that level of advanced care is available to women in that state. If ectogenesis advances further, the limit could be moved to keep pace.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that over 90% of abortions in America are performed at or before 13 weeks, meaning that in the short term, only a small number women would be affected by shifting viability standards. Yet these women are in difficult situations and deserve care and consideration. Research has shown that women seeking later terminations often did not recognize that they were pregnant or had their dates quite wrong, while others report that they had trouble accessing a termination earlier in pregnancy, were afraid to tell their partner or parents, or only recently received a diagnosis of health problems with the fetus.

Shifts in viability over the past few decades have already affected these women, many of whom report struggling to find a provider willing to perform a termination at 18 or 20 weeks out of concern that the woman may have her dates wrong. Ever-earlier gestational limits would continue this chilling effect, making doctors leery of terminating a pregnancy that might be within 2–4 weeks of each new ban. Some states' existing gestational limits on abortion are also inconsistent with prenatal care, which includes genetic testing between 12 and 20 weeks' gestation, as well as an anatomy scan to check the fetus's organ development performed at approximately 20 weeks. If viability moves earlier, prenatal care will be further undermined.

Perhaps most importantly, earlier and earlier abortion bans are inconsistent with the rights and freedoms on which abortion access is based, including recognition of each woman's individual right to bodily integrity and decision-making authority over her own medical care. Those rights and freedoms become meaningless if abortion bans encroach into the weeks that women need to recognize they are pregnant, assess their options, seek medical advice, and access appropriate care. Fetal viability, with its shifting goalposts, isn't the best framework for abortion protection in light of advancing medical science.

Ideally, whether to have an abortion would be a decision that women make in consultation with their doctors, free of state interference. The vast majority of women already make this decision early in pregnancy; the few who come to the decision later do so because something has gone seriously wrong in their lives or with their pregnancies. If states insist on drawing lines based on historical measures of viability, at 24 or 26 or 28 weeks, they should stick with those gestational limits and admit that they no longer represent actual viability but correspond instead to some form of common morality about when the fetus has a protected, if not absolute, right to life. Women need a reasonable amount of time to make careful and informed decisions about whether to continue their pregnancies precisely because these decisions have a lasting impact on their bodies and their lives. To preserve that time, legislators and the courts should decouple abortion rights from ectogenesis and other advances in the care of extremely premature infants that move the point of viability ever earlier.

[Editor's Note: This article was updated after publication to reflect Amy Coney Barrett's confirmation. To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the e-reader version.]

A Mother-and-Daughter Team Have Developed What May Be the World’s First Alzheimer’s Vaccine

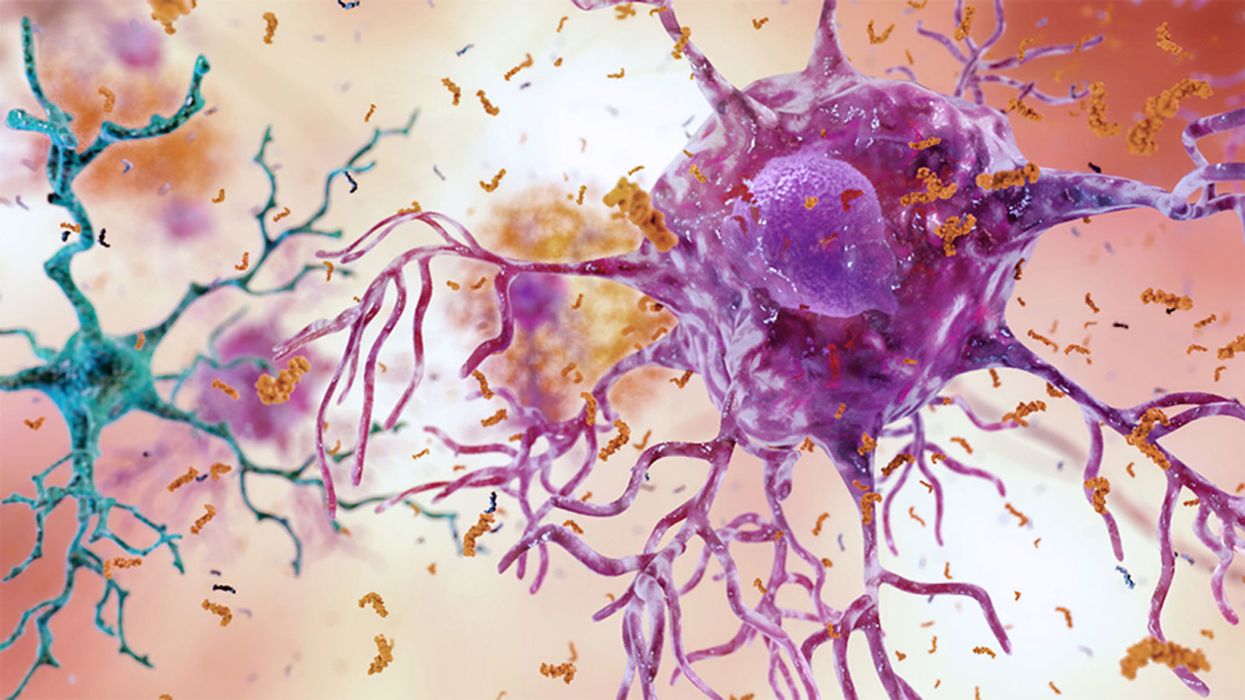

Brain inflammation from Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's is a terrible disease that robs a person of their personality and memory before eventually leading to death. It's the sixth-largest killer in the U.S. and, currently, there are 5.8 million Americans living with the disease.

Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

It devastates people and families and it's estimated that Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia will cost the U.S. $290 billion dollars this year alone. It's estimated that it will become a trillion-dollar-a-year disease by 2050.

There have been over 200 unsuccessful attempts to find a cure for the disease and the clinical trial termination rate is 98 percent.

Alzheimer's is caused by plaque deposits that develop in brain tissue that become toxic to brain cells. One of the major hurdles to finding a cure for the disease is that it's impossible to clear out the deposits from the tissue. So scientists have turned their attention to early detection and prevention.

One very encouraging development has come out of the work done by Dr. Chang Yi Wang, PhD. Wang is a prolific bio-inventor; one of her biggest successes is developing a foot-and-mouth vaccine for pigs that has been administered more than three billion times.

Mei Mei Hu

Brainstorm Health / Flickr.

In January, United Neuroscience, a biotech company founded by Yi, her daughter Mei Mei Hu, and son-in-law, Louis Reese, announced the first results from a phase IIa clinical trial on UB-311, an Alzheimer's vaccine.

The vaccine has synthetic versions of amino acid chains that trigger antibodies to attack Alzheimer's protein the blood. Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

"We were able to generate some antibodies in all patients, which is unusual for vaccines," Yi told Wired. "We're talking about almost a 100 percent response rate. So far, we have seen an improvement in three out of three measurements of cognitive performance for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease."

The researchers also claim it can delay the onset of the disease by five years. While this would be a godsend for people with the disease and their families, according to Elle, it could also save Medicare and Medicaid more than $220 billion.

"You'd want to see larger numbers, but this looks like a beneficial treatment," James Brown, director of the Aston University Research Centre for Healthy Ageing, told Wired. "This looks like a silver bullet that can arrest or improve symptoms and, if it passes the next phase, it could be the best chance we've got."

"A word of caution is that it's a small study," says Drew Holzapfel, acting president of the nonprofit UsAgainstAlzheimer's, said according to Elle. "But the initial data is compelling."

The company is now working on its next clinical trial of the vaccine and while hopes are high, so is the pressure. The company has already invested $100 million developing its vaccine platform. According to Reese, the company's ultimate goal is to create a host of vaccines that will be administered to protect people from chronic illness.

"We have a 50-year vision -- to immuno-sculpt people against chronic illness and chronic aging with vaccines as prolific as vaccines for infectious diseases," he told Elle.

[Editor's Note: This article was originally published by Upworthy here and has been republished with permission.]

Turning Algae Into Environmentally Friendly Fuel Just Got Faster and Smarter

Algae in the Mediterranean sea.

Was your favorite beach closed this summer? Algae blooms are becoming increasingly the reason to blame and, as the climate heats up, scientists say we can expect more of the warm water-loving blue-green algae to grow.

"We have removed a significant development barrier to make algal biofuel production more efficient and smarter."

Oddly enough, the pesky growth could help fuel our carbon-friendly options.

This year, the University of Utah scientists discovered a faster way to turn algae into fuel. Algae is filled with lipids that we can feed our energy-hungry diesel engines. The problem is extracting the lipids, which usually requires more energy to transform than the actual energy we'd get – not achieving what scientists call "energy parity."

But now, the University of Utah team has discovered a new mix that is more efficient and much faster. We can now extract more power from algae with less waste materials after the fact. Paper co-author Dr. Leonard Pease says, "We have removed a significant development barrier to make algal biofuel production more efficient and smarter. Our method puts us much closer to creating biofuels energy parity than we were before."

Next Up

Algae has a lot going for it as an alternative fuel source. It grows fast and easily, absorbs carbon dioxide, does not compete with food crops for land, and could produce up to 60 times more oil than standard land-based energy crops, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Yet the costs of algal biofuel production are still expensive for now.

According to Science Daily, only about five percent of total primary energy use in the United States came from algae and other biomass forms. By making the process more efficient, America and other nations could potentially begin relying on more plentiful resources – which, ironically, are more common now because of climate change.

Algae fuel efficiency is already a proven concept. A decade ago, Continental Airlines completed a 90-minute Boeing 737-800 flight with one engine split between biofuel and aircraft fuel. The biofuel was straight from algae. (Other flights were done based on nut fuel and other alternative sources.) The commercial airplane required no modification to the engine and the biofuel itself exceeded the standards of traditional jet fuel.

The problem, as noted at the time, is that biofuels derived from algae had yet to be proven as "commercially competitive."

The University of Utah's discovery could mean cheaper processing. At this point, it is less about if it works and more about if it is a practical alternative.

However, it's unclear how long it will take for algae to become more mainstream, if ever.

Open Questions

Higher efficiency and simpler transformations could mean lower prices and more business access. However, it's unclear how long it will take for algae to become more mainstream, if ever. The algae biofuel worked great for a relatively sophisticated Boeing 737 engine, but your family car, the cross-country delivery trucks and other less powerful machines may need to be modified – and that means the industry-at-large would have to revise their products in order to support the change.

Future-focused groups are already looking at how algae can fuel our space programs, especially if it is more renewable, safe and, potentially, cheaper than our traditional fuel choices. But first, it is worth waiting and seeing if corporations and, later, citizens are willing to take the plunge.