Abortions Before Fetal Viability Are Legal: Might Science and the Change on the Supreme Court Undermine That?

The United States Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C.

This article is part of the magazine, "The Future of Science In America: The Election Issue," co-published by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and GOOD.

Viability—the potential for a fetus to survive outside the womb—is a core dividing line in American law. For almost 50 years, the Supreme Court of the United States has struck down laws that ban all or most abortions, ruling that women's constitutional rights include choosing to end pregnancies before the point of viability. Once viability is reached, however, states have a "compelling interest" in protecting fetal life. At that point, states can choose to ban or significantly restrict later-term abortions provided states allow an exception to preserve the life or health of the mother.

This distinction between a fetus that could survive outside its mother's body, albeit with significant medical intervention, and one that could not, is at the heart of the court's landmark 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade. The framework of viability remains central to the country's abortion law today, even as some states have passed laws in the name of protecting women's health that significantly undermine Roe. Over the last 30 years, the Supreme Court has upheld these laws, which have the effect of restricting pre-viability abortion access, imposing mandatory waiting periods, requiring parental consent for minors, and placing restrictions on abortion providers.

Viability has always been a slippery notion on which to pin legal rights.

Today, the Guttmacher Institute reports that more than half of American women live in states whose laws are considered hostile to abortion, largely as a result of these intrusions on pre-viability abortion access. Nevertheless, the viability framework stands: while states can pass pre-viability abortion restrictions that (ostensibly) protect the health of the woman or that strike some kind a balance between women's rights and fetal life, it is only after viability that they can completely favor fetal life over the rights of the woman (with limited exceptions when the woman's life is threatened). As a result, judges have struck down certain states' so-called heartbeat laws, which tried to prohibit abortions after detection of a fetal heartbeat (as early as six weeks of pregnancy). Bans on abortion after 12 or 15 weeks' gestation have also been reversed.

Now, with a new Supreme Court Justice expected to be hostile to abortion rights, advances in the care of preterm babies and ongoing research on artificial wombs suggest that the point of viability is already sooner than many assume and could soon be moved radically earlier in gestation, potentially providing a legal basis for earlier and earlier abortion bans.

Viability has always been a slippery notion on which to pin legal rights. It represents an inherently variable and medically shifting moment in the pregnancy timeline that the Roe majority opinion declined to firmly define, noting instead that "[v]iability is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks." Even in 1977, this definition was an optimistic generalization. Every baby is different, and while some 28-week infants born the year Roe was decided did indeed live into adulthood, most died at or shortly after birth. The prognosis for infants born at 24 weeks was much worse.

Today, a baby born at 28 weeks' gestation can be expected to do much better, largely due to the development of surfactant treatment in the early 1990s to help ease the air into babies' lungs. Now, the majority of 24-week-old babies can survive, and several very premature babies, born just shy of 22 weeks' gestation, have lived into childhood. All this variability raises the question: Should the law take a very optimistic, if largely unrealistic, approach to defining viability and place it at 22 weeks, even though the overall survival rate for those preemies remains less than 10% today? Or should the law recognize that keeping a premature infant alive requires specialist care, meaning that actual viability differs not just pregnancy-to-pregnancy but also by healthcare facility and from country to country? A 24-week premature infant born in a rural area or in a developing nation may not be viable as a practical matter, while one born in a major U.S. city with access to state-of-the-art care has a greater than 70% chance of survival. Just as some extremely premature newborns survive, some full-term babies die before, during, or soon after birth, regardless of whether they have access to advanced medical care.

To be accurate, viability should be understood as pregnancy-specific and should take into account the healthcare resources available to that woman. But state laws can't capture this degree of variability by including gestation limits in their abortion laws. Instead, many draw a somewhat arbitrary line at 22, 24, or 28 weeks' gestation, regardless of the particulars of the pregnancy or the medical resources available in that state.

As variable and resource-dependent as viability is today, science may soon move that point even earlier. Ectogenesis is a term coined in 1923 for the growth of an organism outside the body. Long considered science fiction, this technology has made several key advances in the past few years, with scientists announcing in 2017 that they had successfully gestated premature lamb fetuses in an artificial womb for four weeks. Currently in development for use in human fetuses between 22 and 23 weeks' gestation, this technology will almost certainly seek to push viability earlier in pregnancy.

Ectogenesis and other improvements in managing preterm birth deserve to be celebrated, offering new hope to the parents of very premature infants. But in the U.S., and in other nations whose abortion laws are fixed to viability, these same advances also pose a threat to abortion access. Abortion opponents have long sought to move the cutoff for legal abortions, and it is not hard to imagine a state prohibiting all abortions after 18 or 20 weeks by arguing that medical advances render this stage "the new viability," regardless of whether that level of advanced care is available to women in that state. If ectogenesis advances further, the limit could be moved to keep pace.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that over 90% of abortions in America are performed at or before 13 weeks, meaning that in the short term, only a small number women would be affected by shifting viability standards. Yet these women are in difficult situations and deserve care and consideration. Research has shown that women seeking later terminations often did not recognize that they were pregnant or had their dates quite wrong, while others report that they had trouble accessing a termination earlier in pregnancy, were afraid to tell their partner or parents, or only recently received a diagnosis of health problems with the fetus.

Shifts in viability over the past few decades have already affected these women, many of whom report struggling to find a provider willing to perform a termination at 18 or 20 weeks out of concern that the woman may have her dates wrong. Ever-earlier gestational limits would continue this chilling effect, making doctors leery of terminating a pregnancy that might be within 2–4 weeks of each new ban. Some states' existing gestational limits on abortion are also inconsistent with prenatal care, which includes genetic testing between 12 and 20 weeks' gestation, as well as an anatomy scan to check the fetus's organ development performed at approximately 20 weeks. If viability moves earlier, prenatal care will be further undermined.

Perhaps most importantly, earlier and earlier abortion bans are inconsistent with the rights and freedoms on which abortion access is based, including recognition of each woman's individual right to bodily integrity and decision-making authority over her own medical care. Those rights and freedoms become meaningless if abortion bans encroach into the weeks that women need to recognize they are pregnant, assess their options, seek medical advice, and access appropriate care. Fetal viability, with its shifting goalposts, isn't the best framework for abortion protection in light of advancing medical science.

Ideally, whether to have an abortion would be a decision that women make in consultation with their doctors, free of state interference. The vast majority of women already make this decision early in pregnancy; the few who come to the decision later do so because something has gone seriously wrong in their lives or with their pregnancies. If states insist on drawing lines based on historical measures of viability, at 24 or 26 or 28 weeks, they should stick with those gestational limits and admit that they no longer represent actual viability but correspond instead to some form of common morality about when the fetus has a protected, if not absolute, right to life. Women need a reasonable amount of time to make careful and informed decisions about whether to continue their pregnancies precisely because these decisions have a lasting impact on their bodies and their lives. To preserve that time, legislators and the courts should decouple abortion rights from ectogenesis and other advances in the care of extremely premature infants that move the point of viability ever earlier.

[Editor's Note: This article was updated after publication to reflect Amy Coney Barrett's confirmation. To read other articles in this special magazine issue, visit the e-reader version.]

He Almost Died from a Deadly Superbug. A Virus Saved Him.

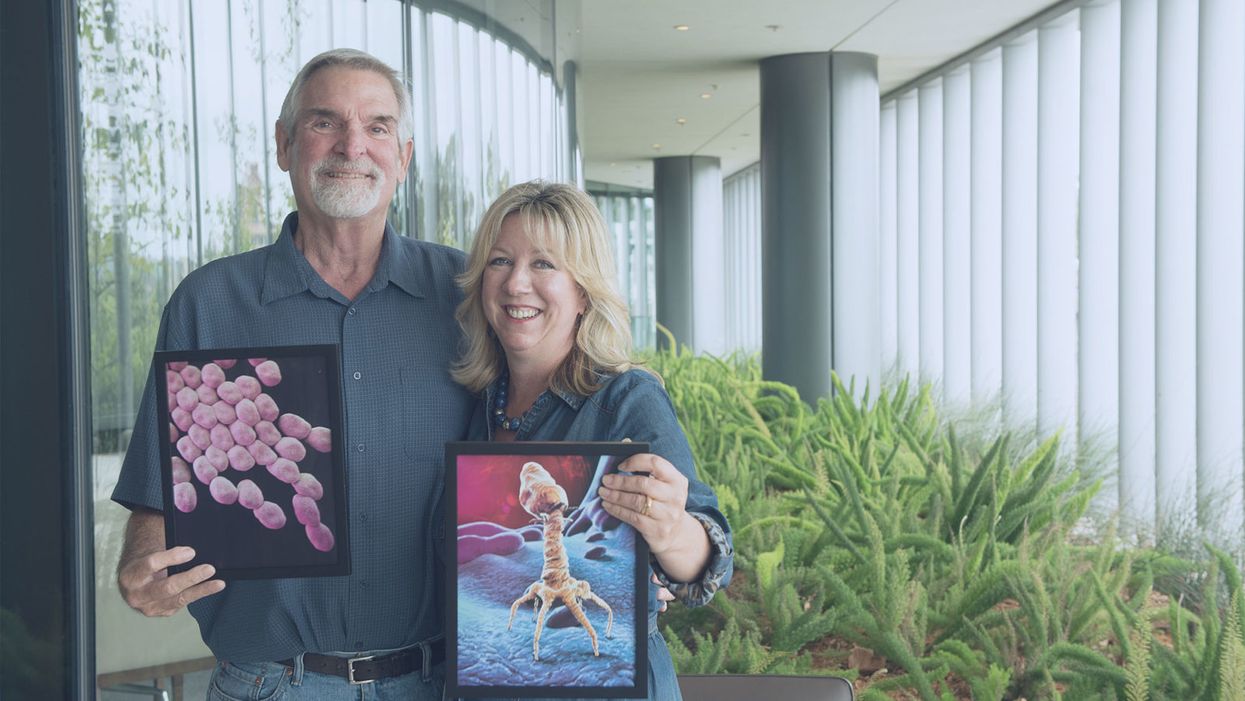

Tom Patterson holding an image of Acinetobacter baumannii and Steffanie Strathdee holding an image of a bacteriophage.

An attacking rogue hippo, giant jumping spiders, even a coup in Timbuktu couldn't knock out Tom Patterson, but now he was losing the fight against a microscopic bacteria.

Death seemed inevitable, perhaps hours away, despite heroic efforts to keep him alive.

It was the deadly drug-resistant superbug Acinetobacter baumannii. The infection struck during a holiday trip with his wife to the pyramids in Egypt and had sent his body into toxic shock. His health was deteriorating so rapidly that his insurance company paid to medevac him first to Germany, then home to San Diego.

Weeks passed as he lay in a coma, shedding more than a hundred pounds. Several major organs were on the precipice of collapse, and death seemed inevitable, perhaps hours away despite heroic efforts by a major research university hospital to keep Tom alive.

Tom Patterson in a deep coma on March 14, 2016, the day before phage therapy was initiated.

(Courtesy Steffanie Strathdee)

Then doctors tried something boldly experimental -- injecting him with a cocktail of bacteriophages, tiny viruses that might infect and kill the bacteria ravaging his body.

It worked. Days later Tom's eyes fluttered open for a few brief seconds, signaling that the corner had been turned. Recovery would take more weeks in the hospital and about a year of rehabilitation before life began to resemble anything near normal.

In her new book The Perfect Predator, Tom's wife, Steffanie Strathdee, recounts the personal and scientific ordeal from twin perspectives as not only his spouse but also as a research epidemiologist who has traveled the world to track down diseases.

Part of the reason why Steff wrote the book is that both she and Tom suffered severe PTSD after his illness. She says they also felt it was "part of our mission, to ensure that phage therapy wasn't going to be forgotten for another hundred years."

Tom Patterson and Steffanie Strathdee taking a first breath of fresh air during recovery outside the UCSD hospital.

(Courtesy Steffanie Strathdee)

From Prehistoric Arms Race to Medical Marvel

Bacteriophages, or phages for short, evolved as part of the natural ecosystem. They are viruses that infect bacteria, hijacking their host's cellular mechanisms to reproduce themselves, and in the process destroying the bacteria. The entire cycle plays out in about 20-60 minutes, explains Ben Chan, a phage research scientist at Yale University.

They were first used to treat bacterial infections a century ago. But the development of antibiotics soon eclipsed their use as medicine and a combination of scientific, economic, and political factors relegated them to a dusty corner of science. The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria has highlighted the limitations of antibiotics and prompted a search for new approaches, including a revived interest in phages.

Most phages are very picky, seeking out not just a specific type of bacteria, but often a specific strain within a family of bacteria. They also prefer to infect healthy replicating bacteria, not those that are at rest. That's what makes them so intriguing to tap as potential therapy.

Tom's case was one of the first times that phages were successfully infused into the bloodstream of a human.

Phages and bacteria evolved measures and countermeasures to each other in an "arms race" that began near the dawn of life on the planet. It is not that one consciously tries to thwart the other, says Chan, it's that countless variations of each exists in the world and when a phage gains the upper hand and kills off susceptible bacteria, it opens up a space in the ecosystem for similar bacteria that are not vulnerable to the phage to increase in numbers. Then a new phage variant comes along and the cycle repeats.

Robert "Chip" Schooley is head of infectious diseases at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine and a leading expert on treating HIV. He had no background with phages but when Steff, a friend and colleague, approached him in desperation about using them with Tom, he sprang into action to learn all he could, and to create a network of experts who might provide phages capable of killing Acinetobacter.

"There is very little evidence that phage[s] are dangerous," Chip concluded after first reviewing the literature and now after a few years of experience using them. He compares broad-spectrum antibiotics to using a bazooka, where every time you use them, less and less of the "good" bacteria in the body are left. "With a phage cocktail what you're really doing is more of a laser."

Collaborating labs were able to identify two sets of phage cocktails that were sensitive to Tom's particular bacterial infection. And the FDA acted with lightning speed to authorize the experimental treatment.

A bag of a four-phage "cocktail" before being infused into Tom Patterson.

(Courtesy Steffanie Strathdee)

Tom's case was scientifically important because it was one of the first times that phages were successfully infused into the bloodstream of a human. Most prior use of phages involved swallowing them or placing them directly on the area of infection.

The success has since sparked a renewed interest in phages and a reexamination of their possible role in medicine.

Over the two years since Tom awoke from his coma, several other people around the world have been successfully treated with phages as part of their regimen, after antibiotics have failed.

The Future of Phage Therapy

The experience treating Tom prompted UCSD to create the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH), with Chip and Steff as co-directors. Previous labs have engaged in basic research on phages, but this is the first clinical center in North America to focus on translating that knowledge into treating patients.

In January, IPATH announced the first phase 2 clinical trial approved by the FDA that will use phages intravenously. The viruses are being developed by AmpliPhi Biosciences, a San Diego-based company that supplied one of the phages used to treat Tom. The new study takes on drug resistant Staph aureus bacteria. Experimental phage therapy treatment using the company's product candidates was recently completed in 21 patients at seven hospitals who had been suffering from serious infections that did not respond to antibiotics. The reported success rate was 84 percent.

The new era of phage research is applying cutting-edge biologic and informatics tools to better understand and reshape the viruses to better attack bacteria, evade resistance, and perhaps broaden their reach a bit within a bacterial family.

Genetic engineering tools are being used to enhance the phages' ability to infect targeted bacteria.

"As we learn more and more about which biological activities are critical and in which clinical settings, there are going to be ways to optimize these activities," says Chip. Sometimes phages may be used alone, other times in combination with antibiotics.

Genetic engineering using tools are being used to enhance the phages' ability to infect targeted bacteria and better counter evolving forms of bacterial resistance in the ongoing "arms race" between the two. It isn't just theory. A patient recently was successfully treated with a genetically modified phage as part of the regimen, and the paper is in press.

In reality, given the trillions of phages in the world and the endless encounters they have had with bacteria over the millennia, it is likely that the exact phages needed to kill off certain bacteria already exist in nature. Using CRISPR to modify a phage is simply a quick way to identify the right phage useful for a given patient and produce it in the necessary quantities, rather than go search for the proverbial phage needle in a sewage haystack, says Chan.

One non-medical reason why using modified phages could be significant is that it creates an intellectual property stake, something that is patentable with a period of exclusive use. Major pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists have been hesitant to invest in organisms found in nature; but a patentable modification may be enough to draw their interest to phage development and provide the funding for large-scale clinical trials necessary for FDA approval and broader use.

"There are 10 million trillion trillion phages on the planet, 10 to the power of 31. And the fact is that this ongoing evolutionary arms race between bacteria and phage, they've been at it for a millennia," says Steff. "We just need to exploit it."

This Mom Is On a Mission to End Sickle Cell Disease

Adrienne Shapiro and her daughter Marissa, who is the fifth generation of children in the family to inherit sickle cell disease, pose in 2018 for a selfie after a new medicine Endari transformed their lives.

[Editor's Note: This video is the third of a five-part series titled "The Future Is Now: The Revolutionary Power of Stem Cell Research." Produced in partnership with the Regenerative Medicine Foundation, and filmed at the annual 2019 World Stem Cell Summit, this series illustrates how stem cell research will profoundly impact human life.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.