Clever Firm Predicts Patients Most at Risk, Then Tries to Intervene Before They Get Sicker

Health firm Populytics tracks and analyzes patient data, and makes care suggestions based on that data.

The diabetic patient hit the danger zone.

Ideally, blood sugar, measured by an A1C test, rests at 5.9 or less. A 7 is elevated, according to the Diabetes Council. Over 10, and you're into the extreme danger zone, at risk of every diabetic crisis from kidney failure to blindness.

In three months of working with a case manager, Jen's blood sugar had dropped to 7.2, a much safer range.

This patient's A1C was 10. Let's call her Jen for the sake of this story. (Although the facts of her case are real, the patient's actual name wasn't released due to privacy laws.).

Jen happens to live in Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley, home of the nonprofit Lehigh Valley Health Network, which has eight hospital campuses and various clinics and other services. This network has invested more than $1 billion in IT infrastructure and founded Populytics, a spin-off firm that tracks and analyzes patient data, and makes care suggestions based on that data.

When Jen left the doctor's office, the Populytics data machine started churning, analyzing her data compared to a wealth of information about future likely hospital visits if she did not comply with recommendations, as well as the potential positive impacts of outreach and early intervention.

About a month after Jen received the dangerous blood test results, a community outreach specialist with psychological training called her. She was on a list generated by Populytics of follow-up patients to contact.

"It's a very gentle conversation," says Cathryn Kelly, who manages a care coordination team at Populytics. "The case manager provides them understanding and support and coaching." The goal, in this case, was small behavioral changes that would actually stick, like dietary ones.

In three months of working with a case manager, Jen's blood sugar had dropped to 7.2, a much safer range. The odds of her cycling back to the hospital ER or veering into kidney failure, or worse, had dropped significantly.

While the health network is extremely localized to one area of one state, using data to inform precise medical decision-making appears to be the wave of the future, says Ann Mongovern, the associate director of Health Care Ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University in California.

"Many hospitals and hospital systems don't yet try to do this at all, which is striking given where we're at in terms of our general technical ability in this society," Mongovern says.

How It Happened

While many hospitals make money by filling beds, the Lehigh Valley Health Network, as a nonprofit, accepts many patients on Medicaid and other government insurances that don't cover some of the costs of a hospitalization. The area's population is both poorer and older than national averages, according to the U.S. Census data, meaning more people with higher medical needs that may not have the support to care for themselves. They end up in the ER, or worse, again and again.

In the early 2000s, LVHN CEO Dr. Brian Nester started wondering if his health network could develop a way to predict who is most likely to land themselves a pricey ICU stay -- and offer support before those people end up needing serious care.

Embracing data use in such specific ways also brings up issues of data security and patient safety.

"There was an early understanding, even if you go back to the (federal) balanced budget act of 1997, that we were just kicking the can down the road to having a functional financial model to deliver healthcare to everyone with a reasonable price," Nester says. "We've got a lot of people living longer without more of an investment in the healthcare trust."

Popultyics, founded in 2013, was the result of years of planning and agonizing over those population numbers and cost concerns.

"We looked at our own health plan," Nester says. Out of all the employees and dependants on the LVHN's own insurance network, "roughly 1.5 percent of our 25,000 people — under 400 people — drove $30 million of our $130 million on insurance costs -- about 25 percent."

"You don't have to boil the ocean to take cost out of the system," he says. "You just have to focus on that 1.5%."

Take Jen, the diabetic patient. High blood sugar can lead to kidney failure, which can mean weekly expensive dialysis for 20 years. Investing in the data and staff to reach patients, he says, is "pennies compared to $100 bills."

For most doctors, "there's no awareness for providers to know who they should be seeing vs. who they are seeing. There's no incentive, because the incentive is to see as many patients as you can," he says.

To change that, first the LVHN invested in the popular medical management system, Epic. Then, they negotiated with the top 18 insurance companies that cover patients in the region to allow access to their patient care data, which means they have reams of patient history to feed the analytics machine in order to make predictions about outcomes. Nester admits not every hospital could do that -- with 52 percent of the market share, LVHN had a very strong negotiating position.

Third party services take that data and churn out analytics that feeds models and care management plans. All identifying information is stripped from the data.

"We can do predictive modeling in patients," says Populytics President and CEO Gregory Kile. "We can identify care gaps. Those care gaps are noted as alerts when the patient presents at the office."

Kile uses himself as a hypothetical patient.

"I pull up Gregory Kile, and boom, I see a flag or an alert. I see he hasn't been in for his last blood test. There is a care gap there we need to complete."

"There's just so much more you can do with that information," he says, envisioning a future where follow-up for, say, knee replacement surgery and outcomes could be tracked, and either validated or changed.

Ethical Issues at the Forefront

Of course, embracing data use in such specific ways also brings up issues of security and patient safety. For example, says medical ethicist Mongovern, there are many touchpoints where breaches could occur. The public has a growing awareness of how data used to personalize their experiences, such as social media analytics, can also be monetized and sold in ways that benefit a company, but not the user. That's not to say data supporting medical decisions is a bad thing, she says, just one with potential for public distrust if not handled thoughtfully.

"You're going to need to do this to stay competitive," she says. "But there's obviously big challenges, not the least of which is patient trust."

So far, a majority of the patients targeted – 62 percent -- appear to embrace the effort.

Among the ways the LVHN uses the data is monthly reports they call registries, which include patients who have just come in contact with the health network, either through the hospital or a doctor that works with them. The community outreach team members at Populytics take the names from the list, pull their records, and start calling. So far, a majority of the patients targeted – 62 percent -- appear to embrace the effort.

Says Nester: "Most of these are vulnerable people who are thrilled to have someone care about them. So they engage, and when a person engages in their care, they take their insulin shots. It's not rocket science. The rocket science is in identifying who the people are — the delivery of care is easy."

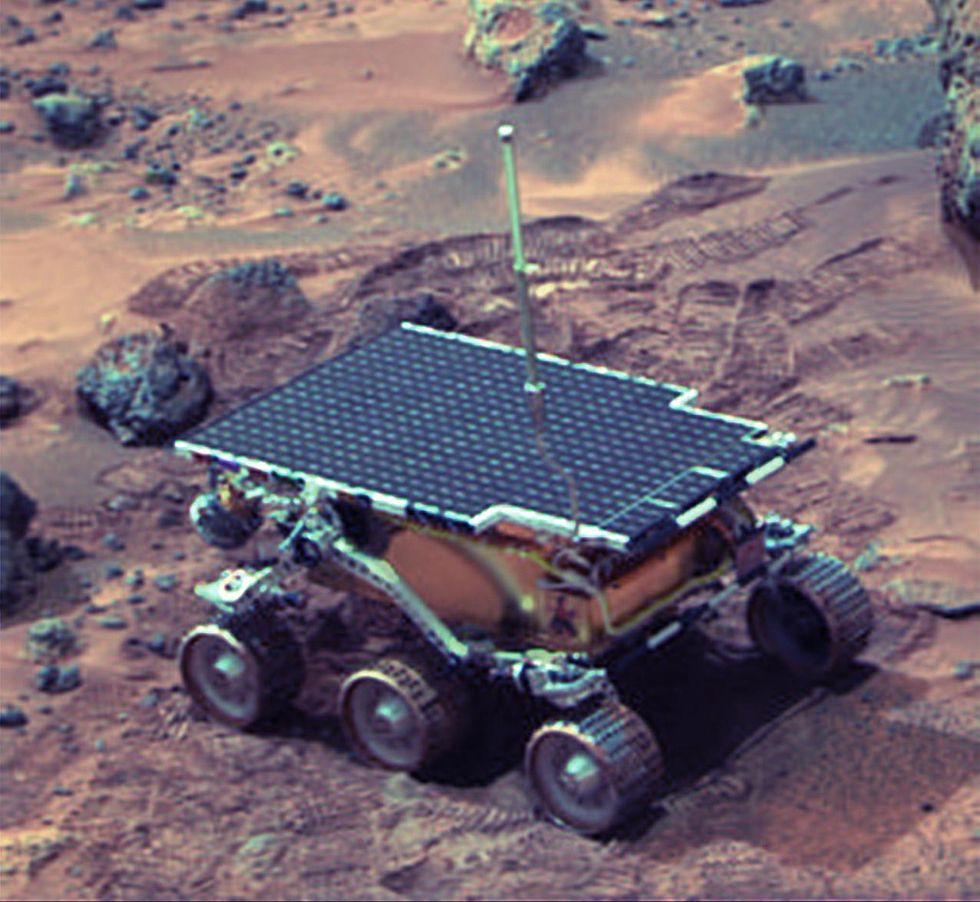

Donna Shirley pictured at her home in Tulsa, with a model of the Sojourner rover she was in charge of that explored Mars.

When NASA's Perseverance rover landed successfully on Mars on February 18, 2021, calling it "one giant leap for mankind" – as Neil Armstrong said when he set foot on the moon in 1969 – would have been inaccurate. This year actually marked the fifth time the U.S. space agency has put a remote-controlled robotic exploration vehicle on the Red Planet. And it was a female engineer named Donna Shirley who broke new ground for women in science as the manager of both the Mars Exploration Program and the 30-person team that built Sojourner, the first rover to land on Mars on July 4, 1997.

For Shirley, the Mars Pathfinder mission was the climax of her 32-year career at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. The Oklahoma-born scientist, who earned her Master's degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Southern California, saw her profile skyrocket with media appearances from CNN to the New York Times, and her autobiography Managing Martians came out in 1998. Now 79 and living in a Tulsa retirement community, she still embraces her status as a female pioneer.

"Periodically, I'll hear somebody say they got into the space program because of me, and that makes me feel really good," Shirley told Leaps.org. "I look at the mission control area, and there are a lot of women in there. I'm quite pleased I was able to break the glass ceiling."

Her $25-million, 25-pound microrover – powered by solar energy and designed to get rock samples and test soil chemistry for evidence of life – was named after Sojourner Truth, a 19th-century Black abolitionist and women's rights activist. Unlike Mars Pathfinder, Shirley didn't have to travel more than 131 million miles to reach her goal, but her path to scientific fame as a woman sometimes resembled an asteroid field.

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.NASA/JPL

The Sojourner Rover in 1997 on Mars.NASA/JPLAs a high-IQ tomboy growing up in Wynnewood, Oklahoma (pop. 2,300), Shirley yearned to escape. She decided to become an engineer at age 10 and took flying lessons at 15. Her extraterrestrial aspirations were fueled by Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles and Arthur C. Clarke's The Sands of Mars. Yet when she entered the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1958, her freshman academic advisor initially told her: "Girls can't be engineers." She ignored him.

Years later, Shirley would combat such archaic thinking, succeeding at JPL with her creative, collaborative management style. "If you look at the literature, you'll find that teams that are either led by or heavily involved with women do better than strictly male teams," she noted.

However, her career trajectory stalled at OU. Burned out by her course load and distracted by a broken engagement to marry a fellow student, she switched her major to professional writing. After graduation, she applied her aeronautical background as a McDonnell Aircraft technical writer, but her boss, she says, harassed her and she faced gender-based hostility from male co-workers.

Returning to OU, Shirley finished off her engineering degree and became a JPL aerodynamist in 1966 after answering an ad in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. At first, she was the only female engineer among the research center's 2,000-odd engineers. She wore many hats, from designing planetary atmospheric entry vehicles to picking the launch date of November 4, 1973 for Mariner 10's mission to Venus and Mercury.

By the mid-1980's, she was managing teams that focused on robotics and Mars, delivering creative solutions when NASA budget cuts loomed. In 1989, the same year the Sojourner microrover concept was born, President George H.W. Bush announced his Space Exploration Initiative, including plans for a human mission to Mars by 2019.

That target, of course, wasn't attained, despite huge advances in technology and our understanding of the Martian environment. Today, Shirley believes humans could land on Mars by 2030. She became the founding director of the Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame in Seattle in 2004 after leaving NASA, and to this day, she enjoys checking out pop culture portrayals of Mars landings – even if they're not always accurate.

After the novel The Martian was published in 2011, which later was adapted into the hit film starring Matt Damon, Shirley phoned author Andy Weir: "You've got a major mistake in here. It says there's a storm that tries to blow the rocket over. But actually, the Mars atmosphere is so thin, it would never blow a rocket over!"

Fearlessly speaking her mind and seeking the stars helped Donna Shirley make history. However, a 2019 Washington Post story noted: "Women make up only about a third of NASA's workforce. They comprise just 28 percent of senior executive leadership positions and are only 16 percent of senior scientific employees." Whether it's traveling to Mars or trending toward gender equality, we've still got a long way to go.

Announcing March Event: "COVID Vaccines and the Return to Life: Part 1"

Leading medical and scientific experts will discuss the latest developments around the COVID-19 vaccines at our March 11th event.

EVENT INFORMATION

DATE:

Thursday, March 11th, 2021 at 12:30pm - 1:45pm EST

On the one-year anniversary of the global declaration of the pandemic, this virtual event will convene leading scientific and medical experts to discuss the most pressing questions around the COVID-19 vaccines. Planned topics include the effect of the new circulating variants on the vaccines, what we know so far about transmission dynamics post-vaccination, how individuals can behave post-vaccination, the myths of "good" and "bad" vaccines as more alternatives come on board, and more. A public Q&A will follow the expert discussion.

CONTACT:

kira@goodinc.com

LOCATION:

Zoom webinar

SPEAKERS:

Dr. Paul Offit speaking at Communicating Vaccine Science.

commons.wikimedia.orgDr. Paul Offit, M.D., is the director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in infectious diseases at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He is a co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine for infants, and he has lent his expertise to the advisory committees that review data on new vaccines for the CDC and FDA.

Dr. Monica Gandhi

UCSF Health

Dr. Monica Gandhi, M.D., MPH, is Professor of Medicine and Associate Division Chief (Clinical Operations/ Education) of the Division of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine at UCSF/ San Francisco General Hospital.

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, FACP, FIDSA

Yale Medicine

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, MBBCh, is an infectious disease physician at Yale Medicine who treats COVID-19 patients and leads Yale's clinical studies around COVID-19. He ran Yale's trial of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

Dr. Eric Topol

Dr. Topol's Twitter

Dr. Eric Topol, M.D., is a cardiologist, scientist, professor of molecular medicine, and the director and founder of Scripps Research Translational Institute. He has led clinical trials in over 40 countries with over 200,000 patients and pioneered the development of many routinely used medications.

REGISTER NOW

This event is the first of a four-part series co-hosted by LeapsMag, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.