Can AI be trained as an artist?

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

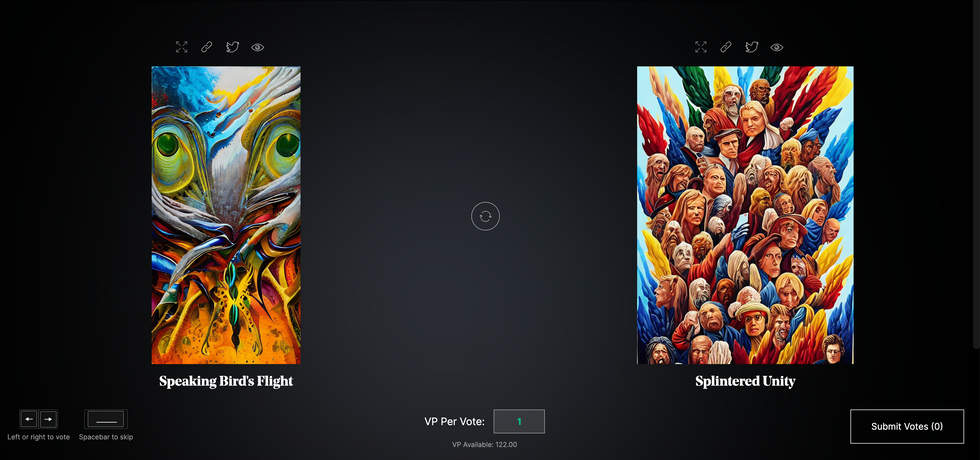

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

Stronger psychedelics that rewire the brain, with Doug Drysdale

Today's podcast episode features Doug Drysdale, CEO of Cybin, a company that is leading innovations in psilocybin, mushrooms that may help people with anxiety and depression.

A promising development in science in recent years has been the use technology to optimize something natural. One-upping nature's wisdom isn't easy. In many cases, we haven't - and maybe we can't - figure it out. But today's episode features a fascinating example: using tech to optimize psychedelic mushrooms.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

These mushrooms have been used for religious, spiritual and medicinal purposes for thousands of years, but only in the past several decades have scientists brought psychedelics into the lab to enhance them and maximize their therapeutic value.

Today’s podcast guest, Doug Drysdale, is doing important work to lead this effort. Drysdale is the CEO of a company called Cybin that has figured out how to make psilocybin more potent, so it can be administered in smaller doses without side effects.

The natural form of psilocybin has been studied increasingly in the realm of mental health. Taking doses of these mushrooms appears to help people with anxiety and depression by spurring the development of connections in the brain, an example of neuroplasticity. The process basically shifts the adult brain from being fairly rigid like dried clay into a malleable substance like warm wax - the state of change that's constantly underway in the developing brains of children.

Neuroplasticity in adults seems to unlock some of our default ways of of thinking, the habitual thought patterns that’ve been associated with various mental health problems. Some promising research suggests that psilocybin causes a reset of sorts. It makes way for new, healthier thought patterns.

So what is Drysdale’s secret weapon to bring even more therapeutic value to psilocybin? It’s a process called deuteration. It focuses on the hydrogen atoms in psilocybin. These atoms are very light and don’t stick very well to carbon, which is another atom in psilocybin. As a result, our bodies can easily breaks down the bonds between the hydrogen and carbon atoms. For many people, that means psilocybin gets cleared from the body too quickly, before it can have a therapeutic benefit.

In deuteration, scientists do something simple but ingenious: they replace the hydrogen atoms with a molecule called deuterium. It’s twice as heavy as hydrogen and forms tighter bonds with the carbon. Because these pairs are so rock-steady, they slow down the rate at which psilocybin is metabolized, so it has more sustained effects on our brains.

Cybin isn’t Drysdale’s first go around at this - far from it. He has over 30 years of experience in the healthcare sector. During this time he’s raised around $4 billion of both public and private capital, and has been named Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the Year. Before Cybin, he was the founding CEO of a pharmaceutical company called Alvogen, leading it from inception to around $500 million in revenues, across 35 countries. Drysdale has also been the head of mergers and acquisitions at Actavis Group, leading 15 corporate acquisitions across three continents.

In this episode, Drysdale walks us through the promising research of his current company, Cybin, and the different therapies he’s developing for anxiety and depression based not just on psilocybin but another psychedelic compound found in plants called DMT. He explains how they seem to have such powerful effects on the brain, as well as the potential for psychedelics to eventually support other use cases, including helping us strive toward higher levels of well-being. He goes on to discuss his views on mindfulness and lifestyle factors - such as optimal nutrition - that could help bring out hte best in psychedelics.

Show links:

Doug Drysdale full bio

Doug Drysdale twitter

Cybin website

Cybin development pipeline

Cybin's promising phase 2 research on depression

Johns Hopkins psychedelics research and psilocybin research

Mets owner Steve Cohen invests in psychedelic therapies

Doug Drysdale, CEO of Cybin

How the body's immune resilience affects our health and lifespan

Immune cells battle an infection.

Story by Big Think

It is a mystery why humans manifest vast differences in lifespan, health, and susceptibility to infectious diseases. However, a team of international scientists has revealed that the capacity to resist or recover from infections and inflammation (a trait they call “immune resilience”) is one of the major contributors to these differences.

Immune resilience involves controlling inflammation and preserving or rapidly restoring immune activity at any age, explained Weijing He, a study co-author. He and his colleagues discovered that people with the highest level of immune resilience were more likely to live longer, resist infection and recurrence of skin cancer, and survive COVID and sepsis.

Measuring immune resilience

The researchers measured immune resilience in two ways. The first is based on the relative quantities of two types of immune cells, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. CD4+ T cells coordinate the immune system’s response to pathogens and are often used to measure immune health (with higher levels typically suggesting a stronger immune system). However, in 2021, the researchers found that a low level of CD8+ T cells (which are responsible for killing damaged or infected cells) is also an important indicator of immune health. In fact, patients with high levels of CD4+ T cells and low levels of CD8+ T cells during SARS-CoV-2 and HIV infection were the least likely to develop severe COVID and AIDS.

Individuals with optimal levels of immune resilience were more likely to live longer.

In the same 2021 study, the researchers identified a second measure of immune resilience that involves two gene expression signatures correlated with an infected person’s risk of death. One of the signatures was linked to a higher risk of death; it includes genes related to inflammation — an essential process for jumpstarting the immune system but one that can cause considerable damage if left unbridled. The other signature was linked to a greater chance of survival; it includes genes related to keeping inflammation in check. These genes help the immune system mount a balanced immune response during infection and taper down the response after the threat is gone. The researchers found that participants who expressed the optimal combination of genes lived longer.

Immune resilience and longevity

The researchers assessed levels of immune resilience in nearly 50,000 participants of different ages and with various types of challenges to their immune systems, including acute infections, chronic diseases, and cancers. Their evaluation demonstrated that individuals with optimal levels of immune resilience were more likely to live longer, resist HIV and influenza infections, resist recurrence of skin cancer after kidney transplant, survive COVID infection, and survive sepsis.

However, a person’s immune resilience fluctuates all the time. Study participants who had optimal immune resilience before common symptomatic viral infections like a cold or the flu experienced a shift in their gene expression to poor immune resilience within 48 hours of symptom onset. As these people recovered from their infection, many gradually returned to the more favorable gene expression levels they had before. However, nearly 30% who once had optimal immune resilience did not fully regain that survival-associated profile by the end of the cold and flu season, even though they had recovered from their illness.

Intriguingly, some people who are 90+ years old still have optimal immune resilience, suggesting that these individuals’ immune systems have an exceptional capacity to control inflammation and rapidly restore proper immune balance.

This could suggest that the recovery phase varies among people and diseases. For example, young female sex workers who had many clients and did not use condoms — and thus were repeatedly exposed to sexually transmitted pathogens — had very low immune resilience. However, most of the sex workers who began reducing their exposure to sexually transmitted pathogens by using condoms and decreasing their number of sex partners experienced an improvement in immune resilience over the next 10 years.

Immune resilience and aging

The researchers found that the proportion of people with optimal immune resilience tended to be highest among the young and lowest among the elderly. The researchers suggest that, as people age, they are exposed to increasingly more health conditions (acute infections, chronic diseases, cancers, etc.) which challenge their immune systems to undergo a “respond-and-recover” cycle. During the response phase, CD8+ T cells and inflammatory gene expression increase, and during the recovery phase, they go back down.

However, over a lifetime of repeated challenges, the immune system is slower to recover, altering a person’s immune resilience. Intriguingly, some people who are 90+ years old still have optimal immune resilience, suggesting that these individuals’ immune systems have an exceptional capacity to control inflammation and rapidly restore proper immune balance despite the many respond-and-recover cycles that their immune systems have faced.

Public health ramifications could be significant. Immune cell and gene expression profile assessments are relatively simple to conduct, and being able to determine a person’s immune resilience can help identify whether someone is at greater risk for developing diseases, how they will respond to treatment, and whether, as well as to what extent, they will recover.