Can AI be trained as an artist?

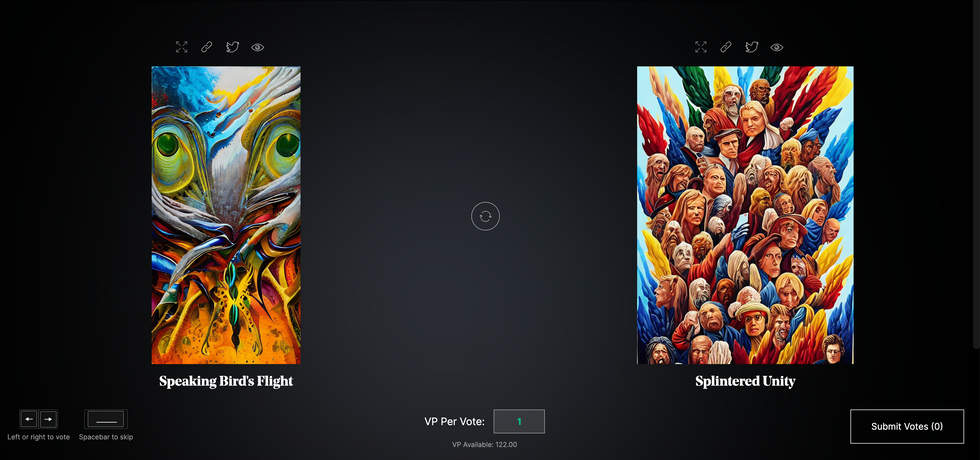

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

World’s First “Augmented Reality” Contact Lens Aims to Revolutionize Much More Than Medicine

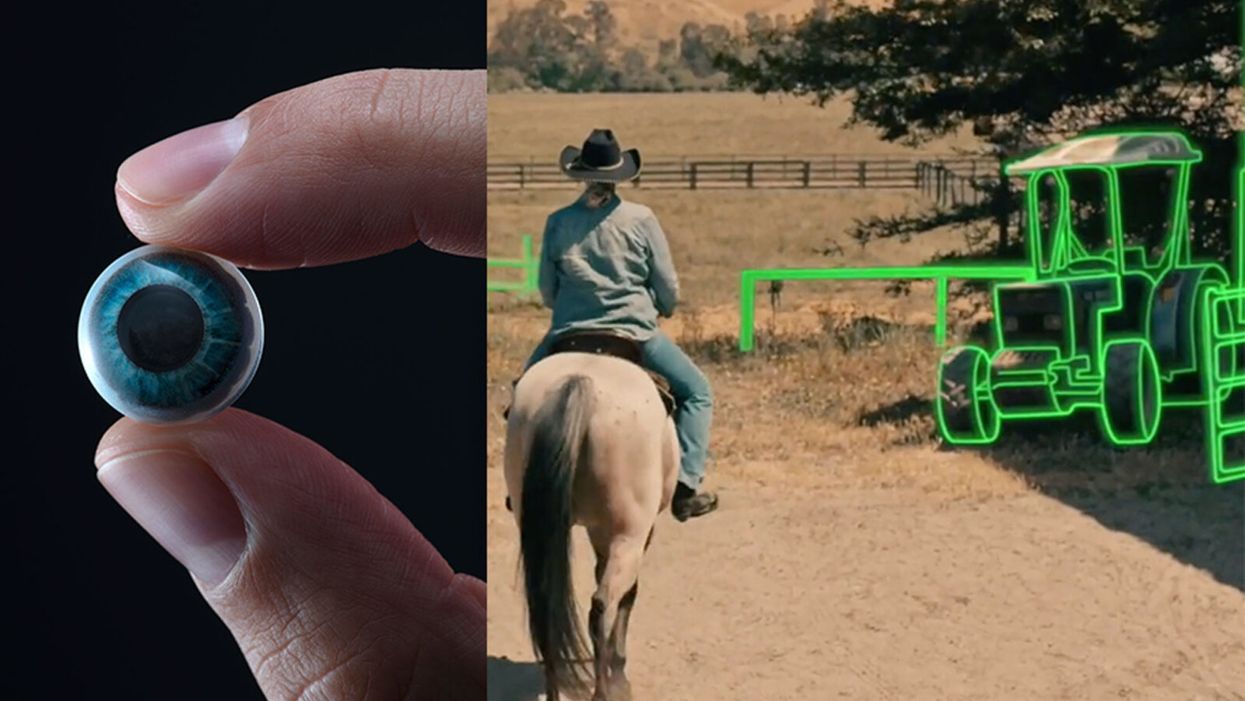

On the left, a picture of the Mojo lens smart contact; and a simulated image of a woman with low vision who is wearing the contact to highlight objects in her field of vision.

Imagine a world without screens. Instead of endlessly staring at your computer or craning your neck down to scroll through social media feeds and emails, information simply appears in front of your eyes when you need it and disappears when you don't.

"The vision is super clear...I was reading the poem with my eyes closed."

No more rude interruptions during dinner, no more bumping into people on the street while trying to follow GPS directions — just the information you want, when you need it, projected directly onto your visual field.

While this screenless future sounds like science fiction, it may soon be a reality thanks to the new Silicon Valley startup Mojo Vision, creator of the world's first smart contact lens. With a 14,000 pixel-per-inch display with eye-tracking, image stabilization, and a custom wireless radio, the Mojo smart lens bills itself the "smallest and densest dynamic display ever made." Unlike current augmented reality wearables such as Google Glass or ThirdEye, which project images onto a glass screen, the Mojo smart lens can project images directly onto the retina.

A current prototype displayed at the Consumer Electronics Show earlier this year in Las Vegas includes a tiny screen positioned right above the most sensitive area of the pupil. "[The Mojo lens] is a contact lens that essentially has wireless power and data transmission for a small micro LED projector that is placed over the center of the eye," explains David Hobbs, Director of Product Management at Mojo Vision. "[It] displays critical heads-up information when you need it and fades into the background when you're ready to continue on with your day."

Eventually, Mojo Visions' technology could replace our beloved smart devices but the first generation of the Mojo smart lens will be used to help the 2.2 billion people globally who suffer from vision impairment.

"If you think of the eye as a camera [for the visually impaired], the sensors are not working properly," explains Dr. Ashley Tuan, Vice President of Medical Devices at Mojo Vision and fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. "For this population, our lens can process the image so the contrast can be enhanced, we can make the image larger, magnify it so that low-vision people can see it or we can make it smaller so they can check their environment." In January of this year, the FDA granted Breakthrough Device Designation to Mojo, allowing them to have early and frequent discussions with the FDA about technical, safety and efficacy topics before clinical trials can be done and certification granted.

For now, Dr. Tuan is one of the few people who has actually worn the Mojo lens. "I put the contact lens on my eye. It was very comfortable like any contact lenses I've worn before," she describes. "The vision is super clear and then when I put on the accessories, suddenly I see Yoda in front of me and I see my vital signs. And then I have my colleague that prepared a beautiful poem that I loved when I was young [and] I was reading the poem with my eyes closed."

At the moment, there are several electronic glasses on the market like Acesight and Nueyes Pro that provide similar solutions for those suffering from visual impairment, but they are large, cumbersome, and highly visible. Mojo lens would be a discreet, more comfortable alternative that offers users more freedom of movement and independence.

"In the case of augmented-reality contact lenses, there could be an opportunity to improve the lives of people with low vision," says Dr. Thomas Steinemann, spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology and professor of ophthalmology at MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. "There are existing tools for people currently living with low vision—such as digital apps, magnifiers, etc.— but something wearable could provide more flexibility and significantly more aid in day-to-day tasks."

As one of the first examples of "invisible computing," the potential applications of Mojo lens in the medical field are endless.

According to Dr. Tuan, the visually impaired often suffer from depression due to their lack of mobility and 70 percent of them are underemployed. "We hope that they can use this device to gain their mobility so they can get that social aspect back in their lives and then, eventually, employment," she explains. "That is our first and most important goal."

But helping those with low visual capabilities is only Mojo lens' first possible medical application; augmented reality is already being used in medicine and is poised to revolutionize the field in the coming decades. For example, Accuvein, a device that uses lasers to provide real-time images of veins, is widely used by nurses and doctors to help with the insertion of needles for IVs and blood tests.

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information, augmentation of reality has been used in surgery for many years with surgeons using devices such as Google Glass to overlay critical information about their patients into their visual field. Using software like the Holographic Navigation Platform by Scopsis, surgeons can see a mixed-reality overlay that can "show you complicated tumor boundaries, assist with implant placements and guide you along anatomical pathways," its developers say.

However, according to Dr. Tuan, augmented reality headsets have drawbacks in the surgical setting. "The advantage of [Mojo lens] is you don't need to worry about sweating or that the headset or glasses will slide down to your nose," she explains "Also, our lens is designed so that it will understand your intent, so when you don't want the image overlay it will disappear, it will not block your visual field, and when you need it, it will come back at the right time."

As one of the first examples of "invisible computing," the potential applications of Mojo lens in the medical field are endless. Possibilities include live translation of sign language for deaf people; helping those with autism to read emotions; and improving doctors' bedside manner by allowing them to fully engage with patients without relying on a computer.

"[By] monitoring those blood vessels we can [track] chronic disease progression: high blood pressure, diabetes, and Alzheimer's."

Furthermore, the lens could be used to monitor health issues. "We have image sensors in the lens right now that point to the world but we can have a camera pointing inside of your eye to your retina," says Dr. Tuan, "[By] monitoring those blood vessels we can [track] chronic disease progression: high blood pressure, diabetes, and Alzheimer's."

For the moment, the future medical applications of the Mojo lens are still theoretical, but the team is confident they can eventually become a reality after going through the proper regulatory review. The company is still in the process of design, prototype and testing of the lens, so they don't know exactly when it will be available for use, but they anticipate shipping the first available products in the next couple of years. Once it does go to market, it will be available by prescription only for those with visual impairments, but the team's goal is to bring it to broader consumer markets pending regulatory clearance.

"We see that right now there's a unique opportunity here for Mojo lens and invisible computing to help to shape what the next decade of technology development looks like," explains David Hobbs. "We can use [the Mojo lens] to better serve us as opposed to us serving technology better."

Schmidt Ocean Institute co-founder Wendy Schmidt is backed by 32 screens in research vessel Falkor's control room where most of the science takes place on the ship, from mapping to live streaming of underwater robotic dives.

WENDY SCHMIDT is a philanthropist and investor who has spent more than a dozen years creating innovative non-profit organizations to solve pressing global environmental and human rights issues. Recognizing the human dependence on sustaining and protecting our planet and its people, Wendy has built organizations that work to educate and advance an understanding of the critical interconnectivity between the land and the sea. Through a combination of grants and investments, Wendy's philanthropic work supports research and science, community organizations, promising leaders, and the development of innovative technologies. Wendy is president of The Schmidt Family Foundation, which she co-founded with her husband Eric in 2006. They also co-founded Schmidt Ocean Institute and Schmidt Futures.

Editors: The pandemic has altered the course of human history and the nature of our daily lives in equal measure. How has it affected the focus of your philanthropy across your organizations? Have any aspects of the crisis in particular been especially galvanizing as you considered where to concentrate your efforts?

Wendy: The COVID-19 pandemic has made the work of our philanthropy more relevant than ever. If anything, the circumstances of this time have validated the focus we have had for nearly 15 years. We support the need for universal access to clean, renewable energy, healthy food systems, and the dignity of human labor and self-determination in a world of interconnected living systems on land and in the Ocean we are only beginning to understand.

When you consider the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 virus on people who are poorly paid, poorly housed, with poor nutrition and health care, and exposed to unsafe conditions in the workplace—you see clearly how the systems that have been defining how we live, what we eat, who gets healthcare and what impacts the environment around us—need to change.

"This moment has propelled broad movements toward open publication and open sharing of data and samples—something that has always been a core belief in how we support and advance science."

If the pandemic teaches us anything, we learn what resilience looks like, and the essential role for local small businesses including restaurants, farms and ranches, dairies and fish markets in the long term vitality of communities. There is resonance, local economic benefit, and also accountability in these smaller systems, with shorter supply chains and less vertical integration.

The consolidation of vertically integrated business operations for the sake of global efficiency reveals its essential weakness when supply chains break down and the failure to encourage local economic centers leads to intense systemic disruption and the possibility of collapse.

Editors: For scientists, one significant challenge has been figuring out how to continue research, if at all, during this time of isolation and distancing. Yet, your research vessel Falkor, of the Schmidt Ocean Institute, is still on its expedition exploring the Coral Sea Marine Park in Australia—except now there are no scientists onboard. What was the vessel up to before the pandemic hit? Can you tell us more about how they are continuing to conduct research from afar now and how that's going?

Wendy: We have been extremely fortunate at Schmidt Ocean Institute. When the pandemic hit in March, our research vessel, Falkor, was already months into a year-long program to research unexplored deep sea canyons around Australia and at the Great Barrier Reef. We were at sea, with an Australian science group aboard, carrying on with our mission of exploration, discovery and communication, when we happened upon what we believe to be the world's longest animal—a siphonophore about 150 feet long, spiraling out at a depth of about 2100 feet at the end of a deeper dive in the Ningaloo Canyon off Western Australia. It was the kind of wondrous creature we find so often when we conduct ROV dives in the world's Ocean.

For more than two months this year, Falkor was reportedly the only research vessel in the world carrying on active research at sea. Once we were able to dock and return the science party to shore, we resumed our program at sea offering a scheduled set of now land-based scientists in lockdown in Australia the opportunity to conduct research remotely, taking advantage of the vessel's ship to shore communications, high resolution cameras and live streaming video. It's a whole new world, and quite wonderful in its own way.

Editors: Normally, 10–15 scientists would be aboard such a vessel. Is "remote research" via advanced video technology here to stay? Are there any upsides to this "new normal"?

Wendy: Like all things pandemic, remote research is an adaptation for what would normally occur. Since we are putting safety of the crew and guest scientists at the forefront, we're working to build strong remote connections between our crew, land based scientists and the many robotic tools on board Falkor. There's no substitute for in person work, but what we've developed during the current cruise is a pretty good and productive alternative in a crisis. And what's important is that this critical scientific research into the deep sea is able to continue, despite the pandemic on land.

Editors: Speaking of marine expeditions, you've sponsored two XPRIZE competitions focused on ocean health. Do you think challenge prizes could fill gaps of the global COVID-19 response, for example, to manufacture more testing kits, accelerate the delivery of PPE, or incentivize other areas of need?

Wendy: One challenge we are currently facing is that innovations don't have the funding pathway to scale, so promising ideas by entrepreneurs, researchers, and even major companies are being developed too slowly. Challenge prizes help raise awareness for problems we are trying to solve and attract new people to help solve those problems by giving them a pathway to contribute.

One idea might be for philanthropy to pair prizes and challenges with an "advanced market commitment" where the government commits to a purchase order for the innovation if it meets a certain test. That could be deeply impactful for areas like PPE and the production of testing kits.

Editors: COVID-19 testing, especially, has been sorely needed, here in the U.S. and in developing countries as well as low-income communities. That's why we're so intrigued by your Schmidt Science Fellows grantee Hal Holmes and his work to repurpose a new DNA technology to create a portable, mobile test for COVID-19. Can you tell us about that work and how you are supporting it?

Wendy: Our work with Conservation X Labs began years ago when our foundation was the first to support their efforts to develop a handheld DNA barcode sensor to help detect illegally imported and mislabeled seafood and timber products. The device was developed by Hal Holmes, who became one of our Schmidt Science Fellows and is the technical lead on the project, working closely with Conservation X Labs co-founders Alex Deghan and Paul Bunje. Now, with COVID-19, Hal and team have worked with another Schmidt Science Fellow, Fahim Farzardfard, to repurpose the technology—which requires no continuous power source, special training, or a lab—to serve as a mobile testing device for the virus.

The work is going very well, manufacturing is being organized, and distribution agreements with hospitals and government agencies are underway. You could see this device in use within a few months and have testing results within hours instead of days. It could be especially useful in low-income communities and developing countries where access to testing is challenging.

Editors: How is Schmidt Futures involved in the development of information platforms that will offer productive solutions?

Wendy: In addition to the work I've mentioned, we've also funded the development of tech-enabled tools that can help the medical community be better prepared for the ongoing spike of COVID cases. For example, we funded EdX and Learning Agency to develop an online training to help increase the number of medical professionals who can operate ventilators. The first course is being offered by Harvard University, and so far, over 220,000 medical professionals have enrolled. We have also invested in informational platforms that make it easier to contain the spread of the disease, such as our work with Recidiviz to model the impact of COVID-19 in prisons and outline policy steps states could take to limit the spread.

Information platforms can also play a big part pushing forward scientific research into the virus. For example, we've funded the UC Santa Cruz Virus Browser, which allows researchers to examine each piece of the virus and see the proteins it creates, the interactions in the host cell, and — most importantly — almost everything the recent scientific literature has to say about that stretch of the molecule.

Editors: The scale of research collaboration and the speed of innovation today seem unprecedented. The whole science world has turned its attention to combating the pandemic. What positive big-picture trends do you think or hope will persist once the crisis eventually abates?

Wendy: As in many areas, the COVID crisis has accelerated trends in the scientific world that were already well underway. For instance, this moment has propelled broad movements toward open publication and open sharing of data and samples—something that has always been a core belief in how we support and advance science.

We believe collaboration is an essential ingredient for progress in all areas. Early in this pandemic, Schmidt Futures held a virtual gathering of 160 people across 70 organizations in philanthropy, government, and business interested in accelerating research and response to the virus, and thought at the time, it's pretty amazing this kind of thing doesn't go all the time. We are obviously going to go farther together than on our own...

My husband, Eric, has observed that in the past two months, we've all catapulted 10 years forward in our use of technology, so there are trends already underway that are likely accelerated and will become part of the fabric of the post-COVID world—like working remotely; online learning; increased online shopping, even for groceries; telemedicine; increasing use of AI to create smarter delivery systems for healthcare and many other applications in a world that has grown more virtual overnight.

"Our deepest hope is that out of these alarming and uncertain times will come a renewed appreciation for the tools of science, as they help humans to navigate a world of interconnected living systems, of which viruses are a large part."

We fully expect these trends to continue and expand across the sciences, sped up by the pressures of the health crisis. Schmidt Ocean Institute and Schmidt Futures have been pressing in these directions for years, so we are pleased to see the expansions that should help more scientists work productively, together.

Editors: Trying to find the good amid a horrible crisis, are there any other new horizons in science, philanthropy, and/or your own work that could transform our world for the better that you'd like to share?

Wendy: Our deepest hope is that out of these alarming and uncertain times will come a renewed appreciation for the tools of science, as they help humans to navigate a world of interconnected living systems, of which viruses are a large part. The more we investigate the Ocean, the more we look deeply into what lies in our soils and beneath them, the more we realize we do not know, and moreover, how vulnerable humanity is to the forces of the natural world.

Philanthropy has an important role to play in influencing how people perceive our place in the world and understand the impact of human activity on the rest of the planet. I believe it's philanthropy's role to take risks, to invest early in innovative technologies, to lead where governments and industry aren't ready to go yet. We're fortunate at this time to be able to help those working on tools to better diagnose and treat the virus, and to invest in those working to improve information systems, so citizens and policy makers can make better decisions that can reduce impacts on families and institutions.

From all we know, this isn't likely to be the last pandemic the world will see. It's been said that a crisis comes before change, and we would hope that we can play a role in furthering the work to build systems that are resilient—in information, energy, agriculture and in all the ways we work, recreate, and use the precious resources of our planet.

[This article was originally published on June 8th, 2020 as part of a standalone magazine called GOOD10: The Pandemic Issue. Produced as a partnership among LeapsMag, The Aspen Institute, and GOOD, the magazine is available for free online.]

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.