Can AI be trained as an artist?

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

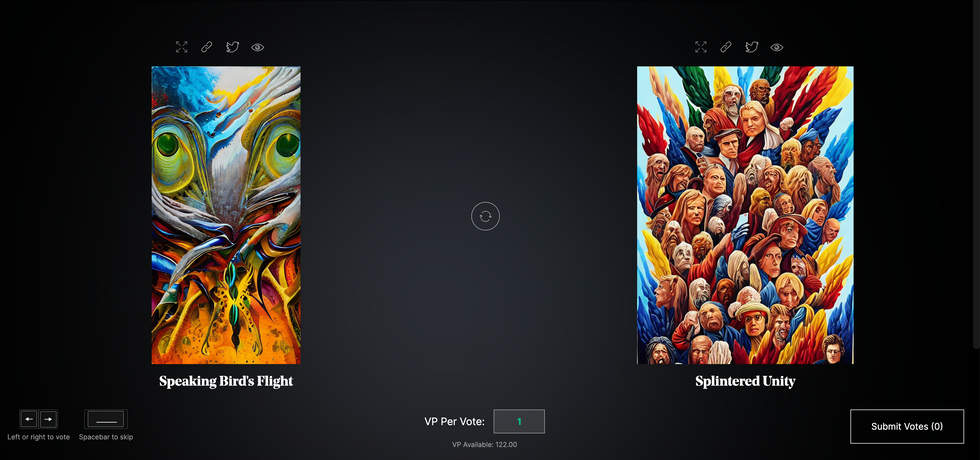

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

As We Wait for a Vaccine, Scientists Work to Scale Up the Best COVID-19 Antibodies to Give New Patients

In this illustration of immune defense, Y-shaped proteins called antibodies attack a virus.

When we get sick, our immune system sends its soldier cells to the battlefield. Called B-cells, they "examine" the foreign particles that shouldn't be in our bloodstream—and start producing the antibodies, the proteins to neutralize the invaders.

To screen the antibodies, scientists have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

The better these antibodies are at neutralizing the pathogen, the faster we recover.

The antibodies acquired from COVID-19 survivors already showed promise in treating other patients, but because they must be obtained from people, generating a regular supply is not feasible. To close the gap, researchers are trying to identify the B-cells that make the best antibodies—and then farm them in laboratories at scale.

Scientists at Berkley Lights, a biotechnology company in California, have been screening B-cells from recovered patients and testing the antibodies they release for virus-neutralizing abilities. To screen the antibodies, scientists there have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

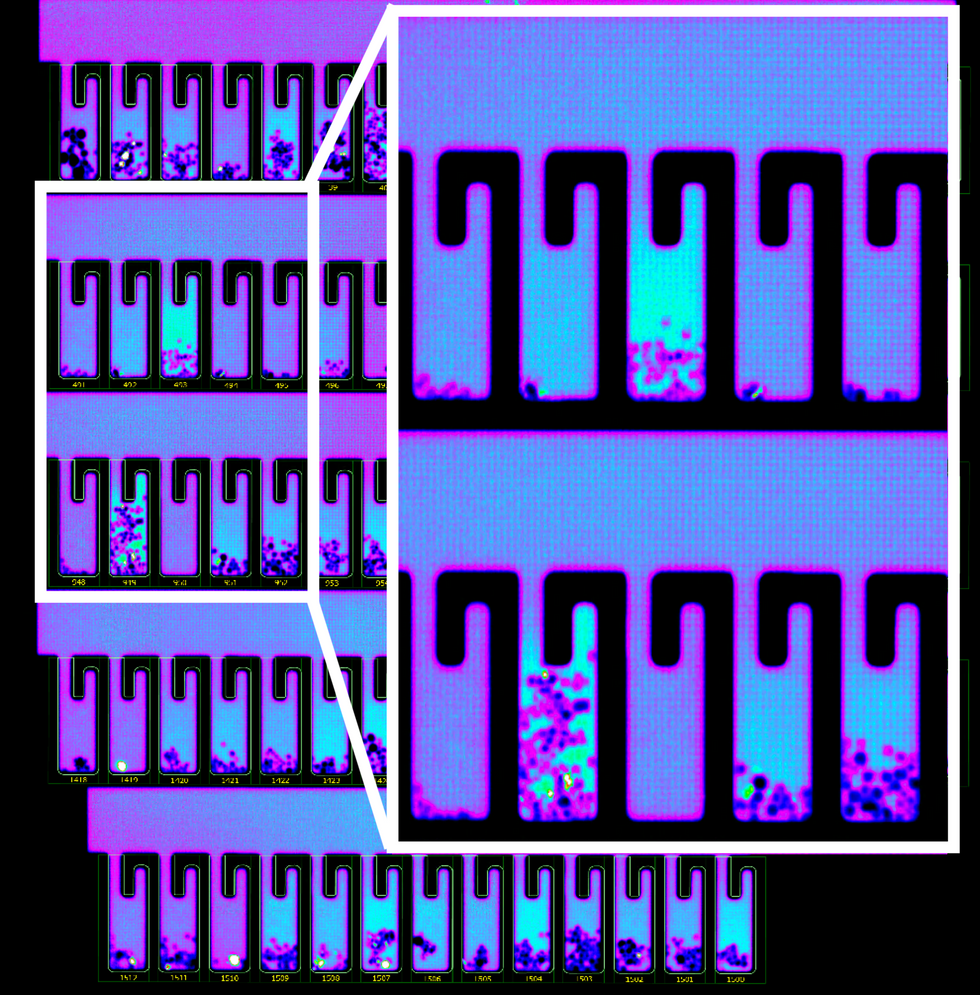

So how does it work? First, the individual B-cells are placed into microscopic chambers called nano-pens, where they secrete the antibodies. Once released, the antibodies are flushed over tiny beads that have bits of the viral particles attached to them, along with special molecules that can emit fluorescent light.

"When an antibody binds to the bead, we see a bright light on the bead," explains John Proctor, the company's senior vice president of antibody therapeutics. "So we can identify which cells are making the antibodies."

Then the antibodies are tested for their ability to counteract the coronavirus's spike proteins, which the virus uses to break into our cells. Not all antibodies are equally good at this crucial defense move—some can block only parts of the virus's machinery, while others can neutralize it completely. Proctor and his colleagues are looking for the latter.

Once scientists identify the best performing B-cells, they crack the cells open—or in scientific terms "lyse" them—and extract the genetic instructions for making the antibodies. As it turns out, B-cells aren't very efficient at pumping out massive amounts of antibodies, so scientists insert these genetic instructions into a different, more prolific type of cell.

Named Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells or CHO, these cells are commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry because they can generate therapeutic proteins en masse. Under the right nutrient conditions, which include a lot of sugar, CHO cells can keep making the antibodies at commercial levels. "They are engineered to operate in very large bioreactors," Proctor explains.

While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours.

Berkeley Lights' technology has already been used to screen the antibodies of recovered patients from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In another example, a biotech company GenScript ProBio used the platform to screen mice engineered to have human antibodies for the coronavirus.

In addition to its small, lab-on-a-chip size, Berkeley Lights' system allows scientists to greatly speed up the screening process. While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours. "We only need one B-cell per pen and a couple of beads to see that fluorescent signal," Proctor says. "It is a more advanced way to process and analyze cells, and that level of sensitivity is unique to our technology."

B-cells secreting antibodies inside the Berkeley Lights Beacon System Nano-Pens.

While vaccines are likely to take months to develop and test, antibodies might arrive to the battleground sooner. With the extremely limited treatment options for COVID-19, antibody-based therapeutics can potentially bridge this gap.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

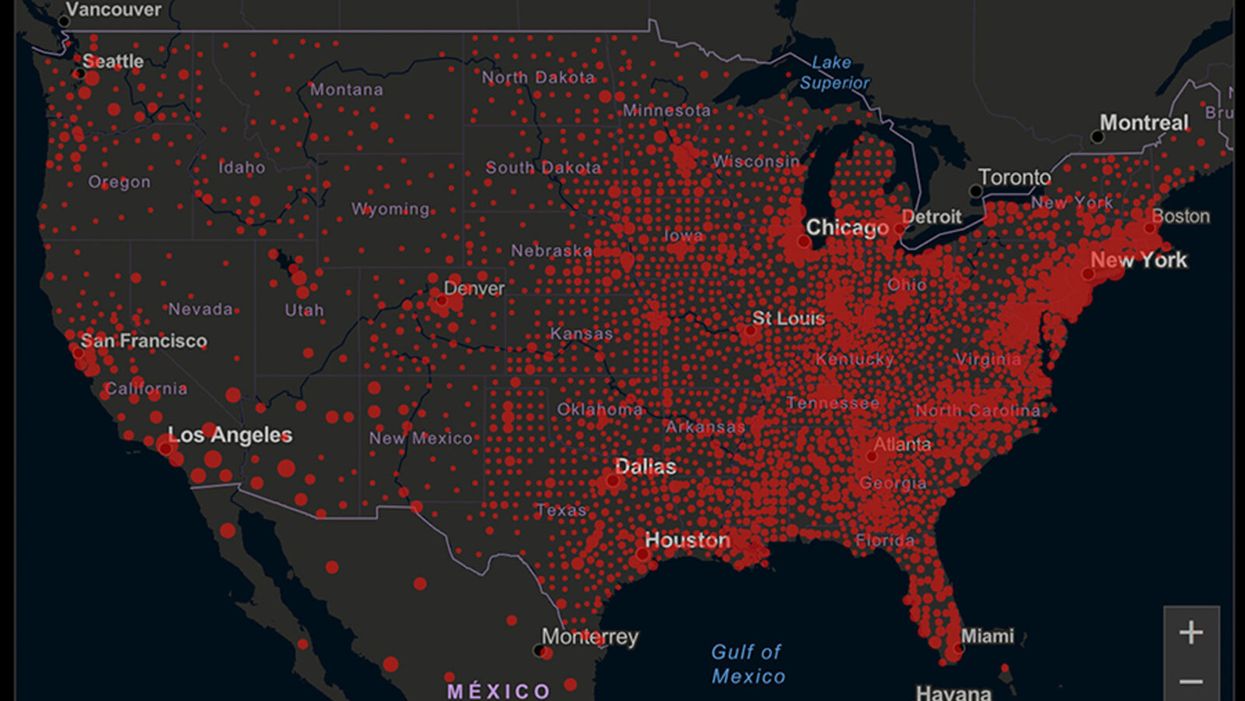

A map of cumulative known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., as of June 12th, 2020.

Have you felt a bit like an armchair epidemiologist lately? Maybe you've been poring over coronavirus statistics on your county health department's website or on the pages of your local newspaper.

If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

You're likely to find numbers and charts but little guidance about how to interpret them, let alone use them to make day-to-day decisions about pandemic safety precautions.

Enter the gurus. We asked several experts to provide guidance for laypeople about how to navigate the numbers. Here's a look at several common COVID-19 statistics along with tips about how to understand them.

Case Counts: Consider the Context

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in American counties is widely available. Local and state health departments should provide them online, or you can easily look them up at The New York Times' coronavirus database. However, you need to be cautious about interpreting them.

"Case counts are the obvious numbers to look at. But they're probably the hardest thing to sort out," said Dr. Jeff Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

That's because case counts by themselves aren't a good window into how the coronavirus is affecting your community since they rely on testing. And testing itself varies widely from day to day and community to community.

"The more testing that's done, the more infections you'll pick up," explained Dr. F. Perry Wilson, a physician at Yale University. The numbers can also be thrown off when tests are limited to certain groups of people.

"If the tests are being mostly given to people with a high probability of having been infected -- for example, they have had symptoms or work in a high-risk setting -- then we expect lots of the tests to be positive. But that doesn't tell us what proportion of the general public is likely to have been infected," said Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

These Stats Are More Meaningful

According to Dr. Wilson, it's more useful to keep two other statistics in mind: the number of COVID tests that are being performed in your community and the percentage that turn up positive, showing that people have the disease. (These numbers may or may not be available locally. Check the websites of your community's health department and local news media outlets.)

If the number of people being tested is going up, but the percentage of positive tests is going down, Dr. Wilson said, that's a good sign. But if both numbers are going up – the number of people tested and the percentage of positive results – then "that's a sign that there are more infections burning in the community."

It's especially worrisome if the percentage of positive cases is growing compared to previous days or weeks, he said. According to him, that's a warning of a "high-risk situation."

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at University of California at San Francisco, offered this tip: If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

There's one more caveat about case counts. It takes an average of a week for someone to be infected with COVID-19, develop symptoms, and get tested, Dr. Rutherford said. It can take an additional several days for those test results to be reported to the county health department. This means that case numbers don't represent infections happening right now, but instead are a picture of the state of the pandemic more than a week ago.

Hospitalizations: Focus on Current Statistics

You should be able to find numbers about how many people in your community are currently hospitalized – or have been hospitalized – with diagnoses of COVID-19. But experts say these numbers aren't especially revealing unless you're able to see the number of new hospitalizations over time and track whether they're rising or falling. This number often isn't publicly available, however.

If new hospitalizations are increasing, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

And there's an important caveat: "The problem with hospitalizations is that they do lag," UC San Francisco's Dr. Martin said, since it takes time for someone to become ill enough to need to be hospitalized. "They tell you how much virus was being transmitted in your community 2 or 2.5 weeks ago."

Also, he said, people should be cautious about comparing new hospitalization rates between communities unless they're adjusted to account for the number of more-vulnerable older people.

Still, if new hospitalizations are increasing, he said, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

Deaths: They're an Even More Delayed Headline

Cable news networks obsessively track the number of coronavirus deaths nationwide, and death counts for every county in the country are available online. Local health departments and media websites may provide charts tracking the growth in deaths over time in your community.

But while death rates offer insight into the disease's horrific toll, they're not useful as an instant snapshot of the pandemic in your community because severely ill patients are typically sick for weeks. Instead, think of them as a delayed headline.

"These numbers don't tell you what's happening today. They tell you how much virus was being transmitted 3-4 weeks ago," Dr. Martin said.

'Reproduction Value': It May Be Revealing

You're not likely to find an available "reproduction value" for your community, but it is available for your state and may be useful.

A reproduction value, also known as R0 or R-naught, "tells us how many people on average we expect will be infected from a single case if we don't take any measures to intervene and if no one has been infected before," said Boston University's Murray.

As The New York Times explained, "R0 is messier than it might look. It is built on hard science, forensic investigation, complex mathematical models — and often a good deal of guesswork. It can vary radically from place to place and day to day, pushed up or down by local conditions and human behavior."

It may be impossible to find the R0 for your community. However, a website created by data specialists is providing updated estimates of a related number -- effective reproduction number, or Rt – for each state. (The R0 refers to how infectious the disease is in general and if precautions aren't taken. The Rt measures its infectiousness at a specific time – the "t" in Rt.) The site is at rt.live.

"The main thing to look at is whether the number is bigger than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently growing in your area, or smaller than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently decreasing in your area," Murray said. "It's also important to remember that this number depends on the prevention measures your community is taking. If the Rt is estimated to be 0.9 in your area and you are currently under lockdown, then to keep it below 1 you may need to remain under lockdown. Relaxing the lockdown could mean that Rt increases above 1 again."

"Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing."

Keep in mind that you can still become infected even if an outbreak in your community appears to be slowing. Low risk doesn't mean no risk.

Putting It All Together: Why the Numbers Matter

So you've reviewed COVID-19 statistics in your community. Now what?

Dr. Wilson suggests using the data to remind yourself that the coronavirus pandemic "is still out there. You need to take it seriously and continue precautions," he said. "Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing. 'My state is doing well, no one I know is sick, is it time to have a dinner party?' No."

He also recommends that laypeople avoid tracking COVID-19 statistics every day. "Check in once a week or twice a month to see how things are going," he suggested. "Don't stress too much. Just let it remind you to put that mask on before you get out of your car [and are around others]."