Can AI be trained as an artist?

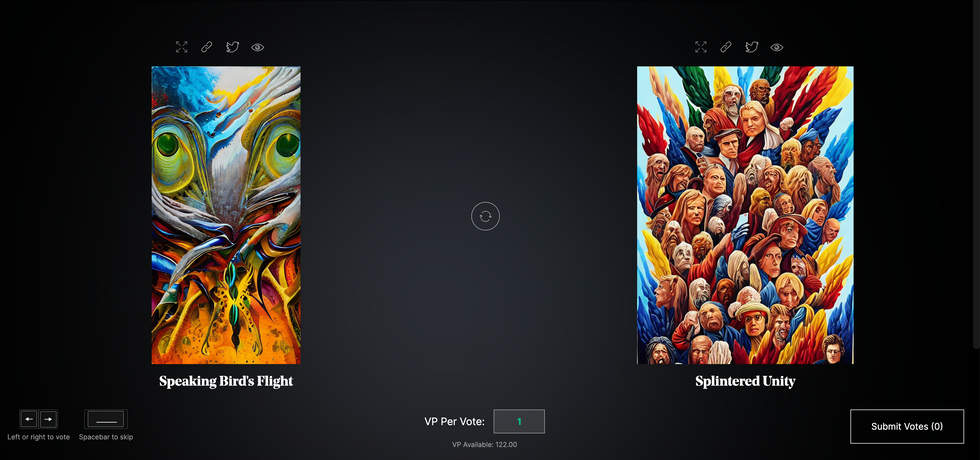

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

Enter our writing contest for a chance to win a cash prize and publication on leapsmag.

Last year, we sponsored a short story contest, asking writers to share a fictional vision of how emerging technology might shape the future. This year, the competition has a new spin.

The Prompt:

Write a personal essay of up to 2000 words describing how a new advance in medicine or science has profoundly affected your life.

The Rules:

Submissions must be received by midnight EST on September 20th, 2019. Send your original, previously unpublished essay as a double-spaced attachment in size 12 Times New Roman font to kira@leapsmag.com. Include your name and a short bio. It is free to enter, and authors retain all ownership of their work. Upon submitting an entry, the author agrees to grant leapsmag one-time nonexclusive publication rights.

All submissions will be judged by the Editor-in-Chief on the basis of insightfulness, quality of writing, and relevance to the prompt. The Contest is open to anyone around the world of any age, except for the friends and family of leapsmag staff and associates.

The winners will be announced by October 31st, 2019.

The Prizes:

Grand Prize: $500, publication of your story on leapsmag, and promotion on our social media channels.

First Runner-Up: $100 and a shout-out on our social media channels.

Good luck!

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Men and Women Experience Pain Differently. Learning Why Could Lead to Better Drugs.

According to the CDC, one fifth of American adults live with chronic pain, and women are affected more than men.

It's been more than a decade since Jeannette Rotondi has been pain-free. A licensed social worker, she lives with five chronic pain diagnoses, including migraines. After years of exploring treatment options, doctors found one that lessened the pain enough to allow her to "at least get up."

"With all that we know now about genetics and the immune system, I think the future of pain medicine is more precision-based."

Before she says, "It was completely debilitating. I was spending time in dark rooms. I got laid off from my job." Doctors advised against pregnancy; she and her husband put off starting a family for almost a decade.

"Chronic pain is very unpredictable," she says. "You cannot schedule when you'll be in debilitative pain or cannot function. You don't know when you'll be hit with a flare. It's constantly in your mind. You have to plan for every possibly scenario. You need to carry water, medications. But you can't plan for everything." Even odors can serve as a trigger.

According to the CDC, one fifth of American adults live with chronic pain, and women are affected more than men. Do men and women simply vary in how much pain they can handle? Or is there some deeper biological explanation? The short answer is it's a little of both. But understanding the biological differences can enable researchers to develop more effective treatments.

While studies in animals are straightforward (they either respond to pain or they don't), humans are more complex. Social and psychological factors can affect the outcome. For example, one Florida study found that gender role expectations influenced pain sensitivity.

"If you are a young male and you believe very strongly that men are tougher than women, you will have a much higher threshold and will be less sensitive to pain," says Robert Sorge, an associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham whose lab researches the immune system's involvement in pain and addiction.

He also notes, "We looked at transgender women and their pain sensitivity in comparison to cis men and women. They show very similar pain sensitivity to cis women, so that may reduce the impact of genetic sex in terms of what underlies that sensitivity."

But the difference goes deeper than gender expectations. There are biological differences as well. In 2015, Sorge and his team discovered that pain stimuli activated different immune cells in male and female rodents and that the presence of testosterone seemed to be a factor in the response.

More recently, Ted Price, professor of neuroscience at University of Texas, Dallas, examined pain at a genetic level, specifically looking at the patterns of RNA, which are single-stranded molecules that act as a messenger for DNA. Price noted that there were differences in these patterns that coincided with whether an individual experienced pain.

Price explains, "Every cell in your body has DNA, but the RNA that is in the cells is different for every cell type. The RNA in any particular cell type, like a neuron, can change as a result of some environmental influence like an injury. We found a number of genes that are potentially causative factors for neuropathic pain. Those, interestingly, seemed to be different between men and women."

Differences in treatment also affect pain response. Sorge says, "Women are experiencing more pain dismissal and more hostility when they report chronic pain. Women are more likely to have their pain associated with psychological issues." He adds that this dismissal may require women to exaggerate symptoms in order to be believed.

This can impact pain management. "Women are more likely to be prescribed and to use opioids," says Dr. Roger B. Fillingim, Director of Pain Research and Intervention Center of Excellence at the University of Florida. Yet, when self-administering pain meds, "women used significantly less opioids after surgery than did men." He also points out that "men are at greater risk for dose escalation and for opioid-related death than are women. So even though more women are using opioids, men are more likely to die from opioid-related causes."

Price acknowledges that other drugs treat pain, but "unfortunately, for chronic pain, none of these drugs work very well. We haven't yet made classes of drugs that really target the underlying mechanism that causes people to have chronic pain."

New drugs are now being developed that "might be particularly efficacious in women's chronic pain."

Sorge points out that there are many variables in pain conditions, so drugs that work for one may be ineffective for another. "With all that we know now about genetics and the immune system, I think the future of pain medicine is more precision-based, where based on your genetics, your immune status, your history, we may eventually get to the point where we can say [certain] drugs have a much bigger chance of working for you."

It will take some time for these new discoveries to translate into effective treatments, but Price says, "I'm excited about the opportunities. DNA and RNA sequencing totally changes our ability to make these therapeutics. I'm very hopeful." New drugs are now being developed that "might be particularly efficacious in women's chronic pain," he says, because they target specific receptors that seem to be involved when only women experience pain.

Earlier this year, three such drugs were approved to treat migraines; Rotondi recently began taking one. For Rotondi, improved treatments would allow her to "show up for life. For me," she says, "it would mean freedom."