Can AI be trained as an artist?

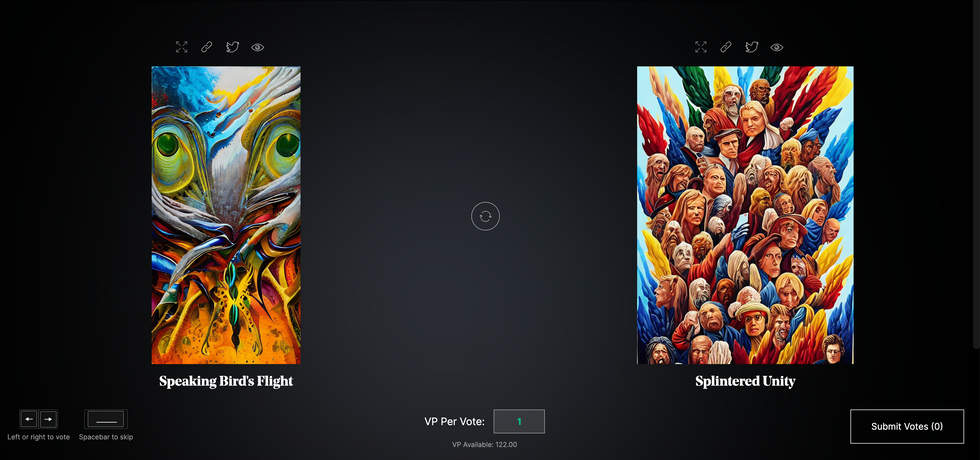

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

Deaf Scientists Just Created Over 1000 New Signs to Dramatically Improve Ability to Communicate

Sarah Latchney, the first deaf PhD student at the University of Rochester School of Medicine & Dentistry, pictured here at work at a lab in the department of environmental sciences.

For the deaf, talent and hard work may not be enough to succeed in the sciences. According to the National Science Foundation, deaf Americans are vastly underrepresented in the STEM fields, a discrepancy that has profound economic implications.

The problem with STEM careers for the deaf and hard-of-hearing is that there are not enough ASL signs available.

Deaf and hard-of-hearing professionals in the sciences earn 31 percent more than those employed in other careers, according to a 2010 study by the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID) in Rochester, N.Y., the largest technical college for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. But at the same time, in 2017, U.S. students with hearing disabilities earned only 1.1 percent of the 39,435 doctoral degrees awarded in science and engineering.

One reason so few deaf students gravitate to science careers and may struggle to complete doctoral programs is the communication chasm between deaf and hard-of-hearing scientists and their hearing colleagues.

Lorne Farovitch is a doctoral candidate in biomedical science at the University of Rochester of New York. Born deaf and raised by two deaf parents, he communicated solely in American Sign Language (ASL) until reaching graduate school. There, he became frustrated at the large chunk of his workdays spent communicating with hearing lab mates and professors, time he would have preferred spending on his scientific work.

The problem with STEM careers for the deaf and hard-of-hearing is that there are not enough ASL signs available, says Farovitch. Names, words, or phrases that don't exist in ASL must be finger spelled — the signer must form a distinct hand shape to correspond with each letter of the English alphabet, a tedious and time-consuming process. For instance, it requires 12 hand motions to spell out the word M-I-T-O-C-H-O-N-D-R-I-A. Imagine repeating those motions countless times a day.

To bust through this linguistic quagmire, Farovitch, along with a team of deaf STEM professionals, linguists, and interpreters, have been cooking up signs for terms like Anaplasma phagocytophilum, the tick-borne bacterium Farovitch studies. The sign creators are then videotaped performing the new signs. Those videos are posted on two crowd-sourcing sites, ASLcore.org and ASL Clear.

The beauty of ASL is you can express an entire concept in a single sign, rather than by the name of a word.

"If others don't pick it up and use it, a sign goes extinct," says Farovitch. Thus far, more than 1,000 STEM terms have been developed on ASL Clear and 500 vetted and approved by the deaf STEM community, according to Jeanne Reis, project director of the ASL Clear Project, based at The Learning Center for the Deaf in Framingham, Mass.

The beauty of ASL is you can express an entire concept in a single sign, rather than by the name of a word. The signs are generally intuitive and wonderfully creative. To express "DNA" Farovitch uses two fingers of each hand touching the tips of the opposite hand; then he draws both the hands away to suggest the double helix form of the hereditary material present in most organisms.

"If you can show it, you can understand the concept better,'' says the Canadian-born scientist. "I feel I can explain science better now."

The hope is that as ASL science vocabulary expands more, deaf and hard-of-hearing students will be encouraged to pursue the STEM fields. "ASL is not just a tool; it's a language. It's a vital part of our lives," Farovitch explains through his interpreter.

The deaf community is diverse—within and beyond the sciences. Sarah Latchney, PhD, an environmental toxicologist, is among the approximately 90 percent of deaf people born to hearing parents. Hers made sure she learned ASL at an early age but they also sent Latchney to a speech therapist to learn to speak and read lips. Latchney is so adept at both that she can communicate one-on-one with a hearing person without an interpreter.

Like Favoritch, Latchney has developed "conceptually accurate" ASL signs but she has no plans to post them on the crowd-sourcing sites. "I don't want to fix [my signs]; it works for me," she explains.

Young scientists like Farovitch and Latchney stress the need for interpreters who are knowledgeable about science. "When I give a presentation I'm a nervous wreck that I'll have an interpreter who may not have a science background," Latchney explains. "Many times what I've [signed] has been misinterpreted; either my interpreter didn't understand the question or didn't frame it correctly."

To enlarge the pool of science-savvy interpreters, the University of Rochester will offer a new masters degree program: ASL Interpreting in Medicine and Science (AIMS), which will train interpreters who have a strong background in the biological sciences.

Since the Americans with Disabilities Act was enacted in 1990, opportunities in higher education for deaf and hard-of-hearing students have opened up in the form of federally funded financial aid and the creation of student disability services on many college campuses. Still, only 18 percent of deaf adults have graduated from college, compared to 33 percent of the general population, according to a survey by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2015.

The University of Rochester and the Rochester Institute of Technology, home to NTID, have jointly created two programs to increase the representation of deaf and hard-of-hearing professionals in the sciences. The Rochester Bridges to the Doctorate Program, which Farovitch is enrolled in, prepares deaf scholars for biomedical PhD programs. The Rochester Postdoctoral Partnership readies deaf postdoctoral scientists to successfully attain academic research and teaching careers. Both programs are funded by the National Institutes of Science. In the last five years, the University of Rochester has gone from zero deaf postdoctoral and graduate students to nine.

"Deafness is not a problem, it's just a difference."

It makes sense for these two private universities to support strong programs for the deaf: Rochester has the highest per capita population of deaf or hard-of-hearing adults younger than 65 in the nation, according to the U.S. Census. According to the U.S. Department of Education, there are about 136,000 post-secondary level students who are deaf or hard of hearing.

"Deafness is not a problem, it's just a difference," says Farovitch. "We just need a different way to communicate. It doesn't mean we require more work."

Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Might Have a New Reason to Ditch Artificial Sweeteners

A mom cradles her newborn baby.

Women considering pregnancy might have another reason to drop artificial sweeteners from their diet, if a new study of mice proves to apply to humans as well. It highlights "yet another potential health impact of zero-calorie sweeteners," according to lead author Stephanie Olivier-Van Stichelen.

The discovery was serendipitous, not part of the original study.

It found that commonly used artificial sweeteners consumed by female mice transfer to pups in the womb and later through milk, harming their development. The sweeteners affected the composition of bacteria in the gut of the pups, making them more vulnerable to developing diabetes, and greatly reduced the liver's capacity to neutralize toxins.

The discovery was serendipitous, not part of the original study, says John Hanover, the senior author and a cell biologist at the NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The main study looked at how a high sugar diet in the mother turns genes on and off in the developing offspring.

It compared them with mothers fed a low sugar diet, replacing sugar with a mix of sucralose and acesulfame-K (AK), two non-nutrient artificial sugars that are already used extensively in our food products and thought to be safe.

While the artificial sweeteners had little effect on the mothers, the trace amounts that were transferred through the placenta and milk had a profound effect on the pups. Hanover believes the molecules are changing gene expression during a crucial, short period of development.

"Somewhat to our surprise, we saw in the pups a really dramatic change in the microbiome" of those whose mothers were fed the artificial sweeteners, Hanover told leapsmag. "It looked like the neonates were much, much more sensitive than their mothers to the sucralose and AK." The unexpected discovery led them to publish a separate paper.

"The protective microbe Akkermansia was largely missing, and we saw a pretty dramatic shift in the ratio of two bacteria that are normally associated with metabolic disease," a precursor to diabetes, he explains. Akkermansia is a bacteria that feeds on mucus in the gut and helps remodel the tissue to an adult state over the first several months of life in a mouse. A similar process takes several years in humans, as the infant is weaned off of breast milk as the primary food source.

The good news is the body seems to remove these artificial sweeteners fairly quickly, probably within a week.

Another problem the researchers saw in the animals was "a particularly striking change in the metabolism of the detoxification systems" in the liver, says Hanover. A healthy liver is dark red, but a high dose of the artificial sweeteners turned it white, "which is a sign of massive problems."

The study was conducted in mice and Hanover cautions the findings may not apply to humans. "But in general, the microbiome changes that one sees in the rodent model mimics what we see in humans...[and] the genes that are turned on in the mouse and the human are very similar."

Hanover acknowledges the quantity of artificial sweeteners used in the study is on the high end of human consumption, roughly the equivalent of 20 cans of diet soda a day. But the sweeteners are so ubiquitous in consumer products, from foods to lipstick, and often not even mentioned on the label, that it is difficult to measure just how much a person consumes every day.

The good news is the body seems to remove these artificial sweeteners fairly quickly, probably within a week. Until further studies provide a clearer picture, women who want to err on the side of caution can choose to reduce if not eliminate their exposure to artificial sweeteners during pregnancy and breastfeeding.