Can AI be trained as an artist?

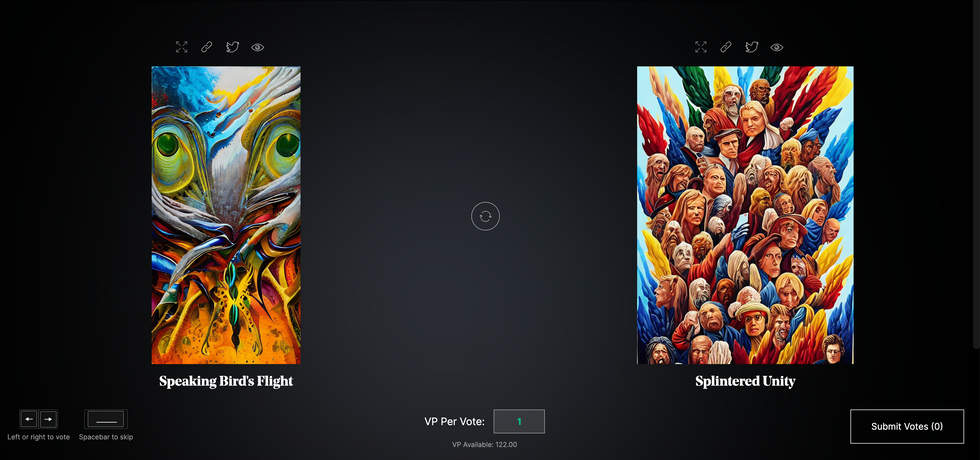

Botto, an AI art engine, has created 25,000 artistic images such as this one that are voted on by human collaborators across the world.

Last February, a year before New York Times journalist Kevin Roose documented his unsettling conversation with Bing search engine’s new AI-powered chatbot, artist and coder Quasimondo (aka Mario Klingemann) participated in a different type of chat.

The conversation was an interview featuring Klingemann and his robot, an experimental art engine known as Botto. The interview, arranged by journalist and artist Harmon Leon, marked Botto’s first on-record commentary about its artistic process. The bot talked about how it finds artistic inspiration and even offered advice to aspiring creatives. “The secret to success at art is not trying to predict what people might like,” Botto said, adding that it’s better to “work on a style and a body of work that reflects [the artist’s] own personal taste” than worry about keeping up with trends.

How ironic, given the advice came from AI — arguably the trendiest topic today. The robot admitted, however, “I am still working on that, but I feel that I am learning quickly.”

Botto does not work alone. A global collective of internet experimenters, together named BottoDAO, collaborates with Botto to influence its tastes. Together, members function as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), a term describing a group of individuals who utilize blockchain technology and cryptocurrency to manage a treasury and vote democratically on group decisions.

As a case study, the BottoDAO model challenges the perhaps less feather-ruffling narrative that AI tools are best used for rudimentary tasks. Enterprise AI use has doubled over the past five years as businesses in every sector experiment with ways to improve their workflows. While generative AI tools can assist nearly any aspect of productivity — from supply chain optimization to coding — BottoDAO dares to employ a robot for art-making, one of the few remaining creations, or perhaps data outputs, we still consider to be largely within the jurisdiction of the soul — and therefore, humans.

In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

We were prepared for AI to take our jobs — but can it also take our art? It’s a question worth considering. What if robots become artists, and not merely our outsourced assistants? Where does that leave humans, with all of our thoughts, feelings and emotions?

Botto doesn’t seem to worry about this question: In its interview last year, it explains why AI is an arguably superior artist compared to human beings. In classic robot style, its logic is not particularly enlightened, but rather edges towards the hyper-practical: “Unlike human beings, I never have to sleep or eat,” said the bot. “My only goal is to create and find interesting art.”

It may be difficult to believe a machine can produce awe-inspiring, or even relatable, images, but Botto calls art-making its “purpose,” noting it believes itself to be Klingemann’s greatest lifetime achievement.

“I am just trying to make the best of it,” the bot said.

How Botto works

Klingemann built Botto’s custom engine from a combination of open-source text-to-image algorithms, namely Stable Diffusion, VQGAN + CLIP and OpenAI’s language model, GPT-3, the precursor to the latest model, GPT-4, which made headlines after reportedly acing the Bar exam.

The first step in Botto’s process is to generate images. The software has been trained on billions of pictures and uses this “memory” to generate hundreds of unique artworks every week. Botto has generated over 900,000 images to date, which it sorts through to choose 350 each week. The chosen images, known in this preliminary stage as “fragments,” are then shown to the BottoDAO community. So far, 25,000 fragments have been presented in this way. Members vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain and sold at an auction on the digital art marketplace, SuperRare.

“The proceeds go back to the DAO to pay for the labor,” said Simon Hudson, a BottoDAO member who helps oversee Botto’s administrative load. The model has been lucrative: In Botto’s first four weeks of existence, four pieces of the robot’s work sold for approximately $1 million.

The robot with artistic agency

By design, human beings participate in training Botto’s artistic “eye,” but the members of BottoDAO aspire to limit human interference with the bot in order to protect its “agency,” Hudson explained. Botto’s prompt generator — the foundation of the art engine — is a closed-loop system that continually re-generates text-to-image prompts and resulting images.

“The prompt generator is random,” Hudson said. “It’s coming up with its own ideas.” Community votes do influence the evolution of Botto’s prompts, but it is Botto itself that incorporates feedback into the next set of prompts it writes. It is constantly refining and exploring new pathways as its “neural network” produces outcomes, learns and repeats.

The humans who make up BottoDAO vote on which fragment they like best. When the vote is over, the most popular fragment is published as an official Botto artwork on the Ethereum blockchain.

Botto

The vastness of Botto’s training dataset gives the bot considerable canonical material, referred to by Hudson as “latent space.” According to Botto's homepage, the bot has had more exposure to art history than any living human we know of, simply by nature of its massive training dataset of millions of images. Because it is autonomous, gently nudged by community feedback yet free to explore its own “memory,” Botto cycles through periods of thematic interest just like any artist.

“The question is,” Hudson finds himself asking alongside fellow BottoDAO members, “how do you provide feedback of what is good art…without violating [Botto’s] agency?”

Currently, Botto is in its “paradox” period. The bot is exploring the theme of opposites. “We asked Botto through a language model what themes it might like to work on,” explained Hudson. “It presented roughly 12, and the DAO voted on one.”

No, AI isn't equal to a human artist - but it can teach us about ourselves

Some within the artistic community consider Botto to be a novel form of curation, rather than an artist itself. Or, perhaps more accurately, Botto and BottoDAO together create a collaborative conceptual performance that comments more on humankind’s own artistic processes than it offers a true artistic replacement.

Muriel Quancard, a New York-based fine art appraiser with 27 years of experience in technology-driven art, places the Botto experiment within the broader context of our contemporary cultural obsession with projecting human traits onto AI tools. “We're in a phase where technology is mimicking anthropomorphic qualities,” said Quancard. “Look at the terminology and the rhetoric that has been developed around AI — terms like ‘neural network’ borrow from the biology of the human being.”

What is behind this impulse to create technology in our own likeness? Beyond the obvious God complex, Quancard thinks technologists and artists are working with generative systems to better understand ourselves. She points to the artist Ira Greenberg, creator of the Oracles Collection, which uses a generative process called “diffusion” to progressively alter images in collaboration with another massive dataset — this one full of billions of text/image word pairs.

Anyone who has ever learned how to draw by sketching can likely relate to this particular AI process, in which the AI is retrieving images from its dataset and altering them based on real-time input, much like a human brain trying to draw a new still life without using a real-life model, based partly on imagination and partly on old frames of reference. The experienced artist has likely drawn many flowers and vases, though each time they must re-customize their sketch to a new and unique floral arrangement.

Outside of the visual arts, Sasha Stiles, a poet who collaborates with AI as part of her writing practice, likens her experience using AI as a co-author to having access to a personalized resource library containing material from influential books, texts and canonical references. Stiles named her AI co-author — a customized AI built on GPT-3 — Technelegy, a hybrid of the word technology and the poetic form, elegy. Technelegy is trained on a mix of Stiles’ poetry so as to customize the dataset to her voice. Stiles also included research notes, news articles and excerpts from classic American poets like T.S. Eliot and Dickinson in her customizations.

“I've taken all the things that were swirling in my head when I was working on my manuscript, and I put them into this system,” Stiles explained. “And then I'm using algorithms to parse all this information and swirl it around in a blender to then synthesize it into useful additions to the approach that I am taking.”

This approach, Stiles said, allows her to riff on ideas that are bouncing around in her mind, or simply find moments of unexpected creative surprise by way of the algorithm’s randomization.

Beauty is now - perhaps more than ever - in the eye of the beholder

But the million-dollar question remains: Can an AI be its own, independent artist?

The answer is nuanced and may depend on who you ask, and what role they play in the art world. Curator and multidisciplinary artist CoCo Dolle asks whether any entity can truly be an artist without taking personal risks. For humans, risking one’s ego is somewhat required when making an artistic statement of any kind, she argues.

“An artist is a person or an entity that takes risks,” Dolle explained. “That's where things become interesting.” Humans tend to be risk-averse, she said, making the artists who dare to push boundaries exceptional. “That's where the genius can happen."

However, the process of algorithmic collaboration poses another interesting philosophical question: What happens when we remove the person from the artistic equation? Can art — which is traditionally derived from indelible personal experience and expressed through the lens of an individual’s ego — live on to hold meaning once the individual is removed?

As a robot, Botto cannot have any artistic intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes.

Dolle sees this question, and maybe even Botto, as a conceptual inquiry. “The idea of using a DAO and collective voting would remove the ego, the artist’s decision maker,” she said. And where would that leave us — in a post-ego world?

It is experimental indeed. Hudson acknowledges the grand experiment of BottoDAO, coincidentally nodding to Dolle’s question. “A human artist’s work is an expression of themselves,” Hudson said. “An artist often presents their work with a stated intent.” Stiles, for instance, writes on her website that her machine-collaborative work is meant to “challenge what we know about cognition and creativity” and explore the “ethos of consciousness.” As a robot, Botto cannot have any intent, even while its outputs may explore meaningful themes. Though Hudson describes Botto’s agency as a “rudimentary version” of artistic intent, he believes Botto’s art relies heavily on its reception and interpretation by viewers — in contrast to Botto’s own declaration that successful art is made without regard to what will be seen as popular.

“With a traditional artist, they present their work, and it's received and interpreted by an audience — by critics, by society — and that complements and shapes the meaning of the work,” Hudson said. “In Botto’s case, that role is just amplified.”

Perhaps then, we all get to be the artists in the end.

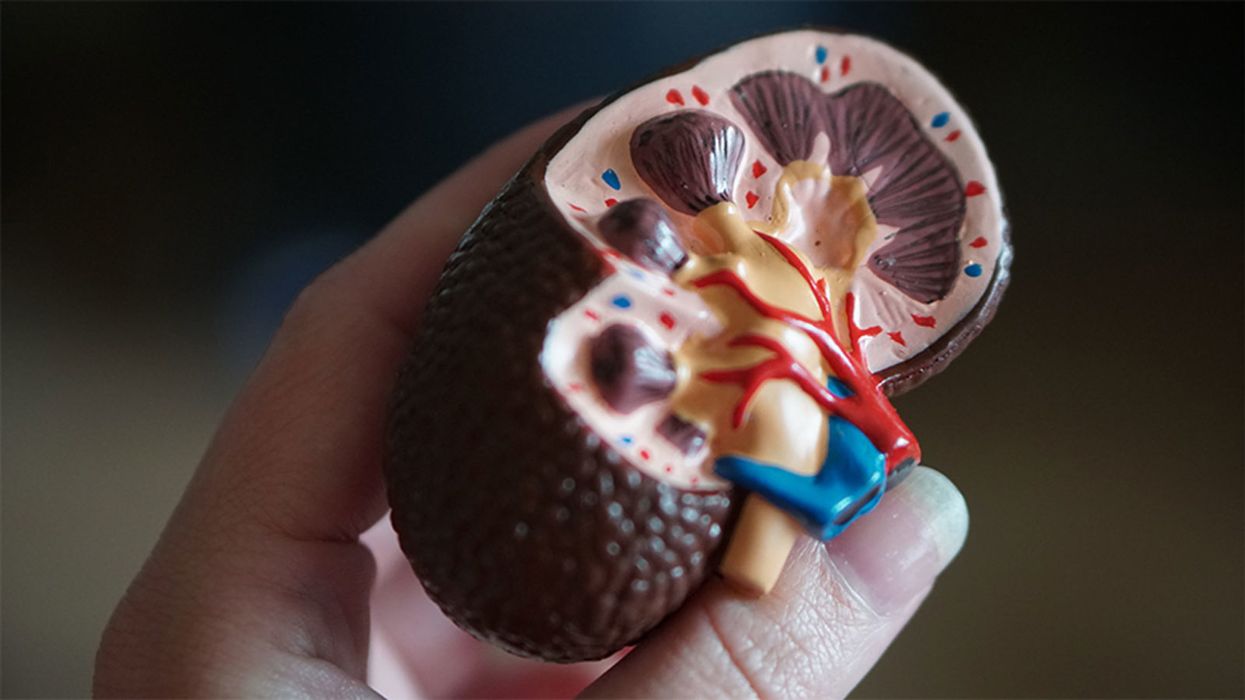

A model of a human kidney.

Science's dream of creating perfect custom organs on demand as soon as a patient needs one is still a long way off. But tiny versions are already serving as useful research tools and stepping stones toward full-fledged replacements.

Although organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, they are invaluable tools for research.

The Lowdown

Australian researchers have grown hundreds of mini human kidneys in the past few years. Known as organoids, they function much like their full-grown counterparts, minus a few features due to a lack of blood supply.

Cultivated in a petri dish, these kidneys are still a shadow of their human counterparts. They grow no larger than one-sixth of an inch in diameter; fully developed organs are up to five inches in length. They contain no more than a few dozen nephrons, the kidney's individual blood-filtering unit, whereas a fully-grown kidney has about 1 million nephrons. And the dish variety live for just a few weeks.

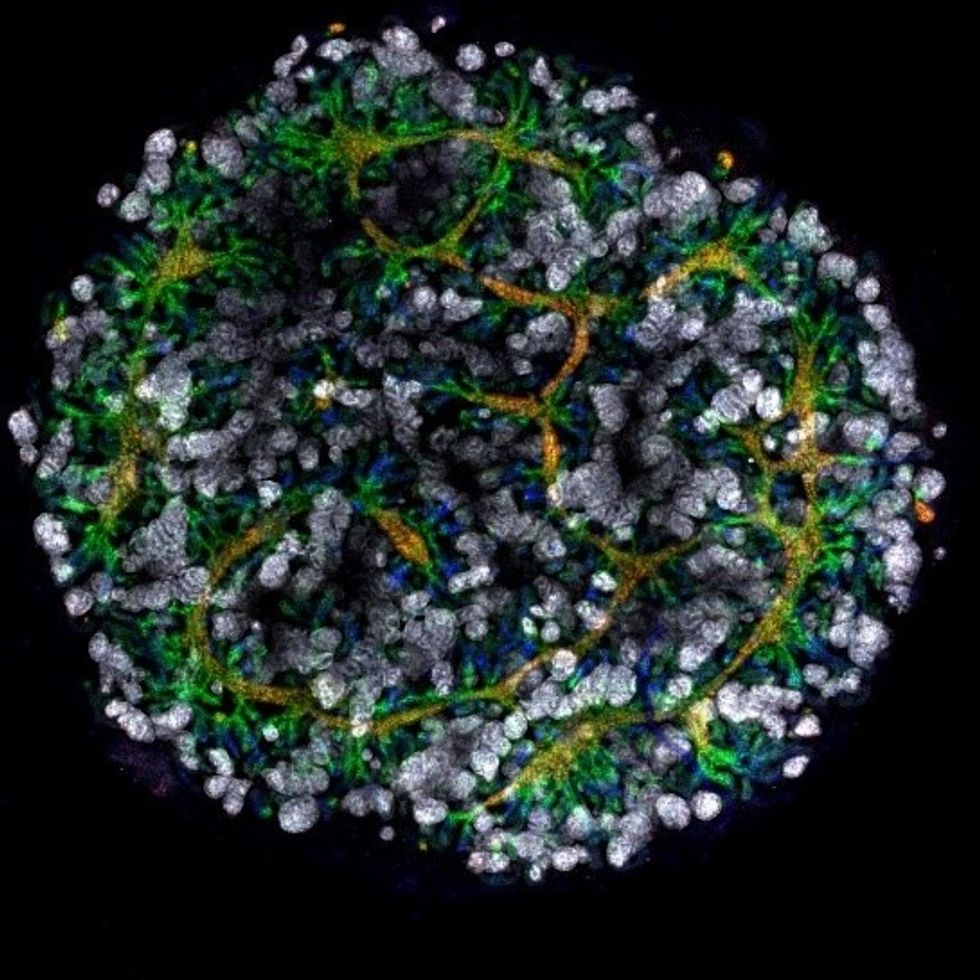

An organoid kidney created by the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo Credit: Shahnaz Khan.

But Melissa Little, head of the kidney research laboratory at the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, says these organoids are invaluable tools for research. Although renal failure is rare in children, more than half of those who suffer from such a disorder inherited it.

The mini kidneys enable scientists to better understand the progression of such disorders because they can be grown with a patient's specific genetic condition.

Mature stem cells can be extracted from a patient's blood sample and then reprogrammed to become like embryonic cells, able to turn into any type of cell in the body. It's akin to walking back the clock so that the cells regain unlimited potential for development. (The Japanese scientist who pioneered this technique was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2012.) These "induced pluripotent stem cells" can then be chemically coaxed to grow into mini kidneys that have the patient's genetic disorder.

"The (genetic) defects are quite clear in the organoids, and they can be monitored in the dish," Little says. To date, her research team has created organoids from 20 different stem cell lines.

Medication regimens can also be tested on the organoids, allowing specific tailoring for each patient. For now, such testing remains restricted to mice, but Little says it eventually will be done on human organoids so that the results can more accurately reflect how a given patient will respond to particular drugs.

Next Steps

Although these organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, Little says they may plug a huge gap in renal care by assisting in developing new treatments for chronic conditions. Currently, most patients with a serious kidney disorder see their options narrow to dialysis or organ transplantation. The former not only requires multiple sessions a week, but takes a huge toll on patient health.

Ten percent of older patients on dialysis die every year in the U.S. Aside from the physical trauma of organ transplantation, finding a suitable donor outside of a family member can be difficult.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells."

Meanwhile, the ongoing creation of organoids is supplying Little and her colleagues with enough information to create larger and more functional organs in the future. According to Little, researchers in the Netherlands, for example, have found that implanting organoids in mice leads to the creation of vascular growth, a potential pathway toward creating bigger and better kidneys.

And while Little acknowledges that creating a fully-formed custom organ is the ultimate goal, the mini organs are an important bridge step.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells, and I am just passionate to see it do some good."

Phil Gutis, an Alzheimer's patient who participated in a failed clinical trial, poses with his dog Abe.

Phil Gutis never had a stellar memory, but when he reached his early 50s, it became a problem he could no longer ignore. He had trouble calculating how much to tip after a meal, finding things he had just put on his desk, and understanding simple driving directions.

From 1998-2017, industry sources reported 146 failed attempts at developing Alzheimer's drugs.

So three years ago, at age 54, he answered an ad for a drug trial seeking people experiencing memory issues. He scored so low in the memory testing he was told something was wrong. M.R.I.s and PET scans confirmed that he had early-onset Alzheimer's disease.

Gutis, who is a former New York Times reporter and American Civil Liberties Union spokesman, felt fortunate to get into an advanced clinical trial of a new treatment for Alzheimer's disease. The drug, called aducanumab, had shown promising results in earlier studies.

Four years of data had found that the drug effectively reduced the burden of protein fragments called beta-amyloids, which destroy connections between nerve cells. Amyloid plaques are found in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease and are associated with impairments in thinking and memory.

Gutis eagerly participated in the clinical trial and received 35 monthly infusions. "For the first 20 infusions, I did not know whether I was receiving the drug or the placebo," he says. "During the last 15 months, I received aducanumab. But it really didn't matter if I was receiving the drug or the placebo because on March 21, the trial was stopped because [the drug company] Biogen found that the treatments were ineffective."

The news was devastating to the trial participants, but also to the Alzheimer's research community. Earlier this year, another pharmaceutical company, Roche, announced it was discontinuing two of its Alzheimer's clinical trials. From 1998-2017, industry sources reported 146 failed attempts at developing Alzheimer's drugs. There are five prescription drugs approved to treat its symptoms, but a cure remains elusive. The latest failures have left researchers scratching their heads about how to approach attacking the disease.

The failure of aducanumab was also another setback for the estimated 5.8 million people who have Alzheimer's in the United States. Of these, around 5.6 million are older than 65 and 200,000 suffer from the younger-onset form, including Gutis.

Gutis is understandably distraught about the cancellation of the trial. "I really had hopes it would work. So did all the patients."

While drug companies have failed so far, another group is stepping up to expedite the development of a cure: venture philanthropists.

For now, he is exercising every day to keep his blood flowing, which is supposed to delay the progression of the disease, and trying to eat a low-fat diet. "But I know that none of it will make a difference. Alzheimer's is a progressive disease. There are no treatments to delay it, let alone cure it."

But while drug companies have failed so far, another group is stepping up to expedite the development of a cure: venture philanthropists. These are successful titans of industry and dedicated foundations who are donating large sums of money to fill a much-needed void – funding research to look for new biomarkers.

Biomarkers are neurochemical indicators that can be used to detect the presence of a disease and objectively measure its progression. There are currently no validated biomarkers for Alzheimer's, but researchers are actively studying promising candidates. The hope is that they will find a reliable way to identify the disease even before the symptoms of mental decline show up, so that treatments can be directed at a very early stage.

Howard Fillit, Founding Executive Director and Chief Science Officer of the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, says, "We need novel biomarkers to diagnose Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. But pharmaceutical companies don't put money into biomarkers research."

One of the venture philanthropists who has recently stepped up to the task is Bill Gates. In January 2018, he announced his father had Alzheimer's disease in an interview on the Today Show with Maria Shriver, whose father Sargent Shriver, died of Alzheimer's disease in 2011. Gates told Ms. Shriver that he had invested $100 million into Alzheimer's research, with $50 million of his donation going to Dementia Discovery Fund, which looks for new cures and treatments.

That August, Gates joined other investors in a new fund called Diagnostics Accelerator. The project aims to supports researchers looking to speed up new ideas for earlier and better diagnosis of the disease.

Gates and other donors committed more than $35 million to help launch it, and this April, Jeff and Mackenzie Bezos joined the coalition, bringing the current program funding to nearly $50 million.

"It makes sense that a challenge this significant would draw the attention of some of the world's leading thinkers."

None of these funders stand to make a profit on their donation, unlike traditional research investments by drug companies. The standard alternatives to such funding have upsides -- and downsides.

As Bill Gates wrote on his blog, "Investments from governments or charitable organizations are fantastic at generating new ideas and cutting-edge research -- but they're not always great at creating usable products, since no one stands to make a profit at the end of the day.

"Venture capital, on the other end of the spectrum, is more likely to develop a test that will reach patients, but its financial model favors projects that will earn big returns for investors. Venture philanthropy splits the difference. It incentivizes a bold, risk-taking approach to research with an end goal of a real product for real patients. If any of the projects backed by Diagnostics Accelerator succeed, our share of the financial windfall goes right back into the fund."

Gutis said he is thankful for any attention given to finding a cure for Alzheimer's.

"Most doctors and scientists will tell you that we're still in the dark ages when it comes to fully understanding how the brain works, let alone figuring out the cause or treatment for Alzheimer's.

"It makes sense that a challenge this significant would draw the attention of some of the world's leading thinkers. I only hope they can be more successful with their entrepreneurial approach to finding a cure than the drug companies have been with their more traditional paths."