How Leqembi became the biggest news in Alzheimer’s disease in 40 years, and what comes next

Betsy Groves, 73, with her granddaughter. Groves learned in 2021 that she has Alzheimer's disease. She hopes to take Leqembi, a drug approved by the FDA last week.

A few months ago, Betsy Groves traveled less than a mile from her home in Cambridge, Mass. to give a talk to a bunch of scientists. The scientists, who worked for the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai, wanted to know how she lived her life, how she thought about her future, and what it was like when a doctor’s appointment in 2021 gave her the worst possible news. Groves, 73, has Alzheimer’s disease. She caught it early, through a lumbar puncture that showed evidence of amyloid, an Alzheimer’s hallmark, in her cerebrospinal fluid. As a way of dealing with her diagnosis, she joined the Alzheimer’s Association’s National Early-Stage Advisory Board, which helped her shift into seeing her diagnosis as something she could use to help others.

After her talk, Groves stayed for lunch with the scientists, who were eager to put a face to their work. Biogen and Eisai were about to release the first drug to successfully combat Alzheimer’s in 40 years of experimental disaster. Their drug, which is known by the scientific name lecanemab and the marketing name Leqembi, was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last Friday, Jan. 6, after a study in 1,800 people showed that it reduced cognitive decline by 27 percent over 18 months.

It is no exaggeration to say that this result is a huge deal. The field of Alzheimer’s drug development has been absolutely littered with failures. Almost everything researchers have tried has tanked in clinical trials. “Most of the things that we've done have proven not to be effective, and it's not because we haven’t been taking a ton of shots at goal,” says Anton Porsteinsson, director of the University of Rochester Alzheimer's Disease Care, Research, and Education Program, who worked on the lecanemab trial. “I think it's fair to say you don't survive in this field unless you're an eternal optimist.”

As far back as 1984, a cure looked like it was within reach: Scientists discovered that the sticky plaques that develop in the brains of those who have Alzheimer’s are made up of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. Buildup of beta-amyloid seemed to be sufficient to disrupt communication between, and eventually kill, memory cells. If that was true, then the cure should be straightforward: Stop the buildup of beta-amyloid; stop the Alzheimer’s disease.

It wasn’t so simple. Over the next 38 years, hundreds of drugs designed either to interfere with the production of abnormal amyloid or to clear it from the brain flamed out in trials. It got so bad that neuroscience drug divisions at major pharmaceutical companies (AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, GSK, Amgen) closed one by one, leaving the field to smaller, scrappier companies, like Cambridge-based Biogen and Tokyo-based Eisai. Some scientists began to dismiss the amyloid hypothesis altogether: If this protein fragment was so important to the disease, why didn’t ridding the brain of it do anything for patients? There was another abnormal protein that showed up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, called tau. Some researchers defected to the tau camp, or came to believe the proteins caused damage in combination.

The situation came to a head in 2021, when the FDA granted provisional approval to a drug called aducanumab, marketed as Aduhelm, against the advice of its own advisory council. The approval was based on proof that Aduhelm reduced beta-amyloid in the brain, even though one research trial showed it had no effect on people’s symptoms or daily life. Aduhelm could also cause serious side effects, like brain swelling and amyloid related imaging abnormalities (known as ARIA, these are basically micro-bleeds that appear on MRI scans). Without a clear benefit to memory loss that would make these risks worth it, Medicare refused to pay for Aduhelm among the general population. Two congressional committees launched an investigation into the drug’s approval, citing corporate greed, lapses in protocol, and an unjustifiably high price. (Aduhelm was also produced by the pharmaceutical company Biogen.)

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world.

So far, Leqembi is like Aduhelm in that it has been given accelerated approval only for its ability to remove amyloid from the brain. Both are monoclonal antibodies that direct the immune system to attack and clear dysfunctional beta-amyloid. The difference is that, while that’s all Aduhelm was ever shown to do, Leqembi’s makers have already asked the FDA to give it full approval – a decision that would increase the likelihood that Medicare will cover it – based on data that show it also improves Alzheimer’s sufferer’s lives. Leqembi targets a different type of amyloid, a soluble version called “protofibrils,” and that appears to change the effect. “It can give individuals and their families three, six months longer to be participating in daily life and living independently,” says Claire Sexton, PhD, senior director of scientific programs & outreach for the Alzheimer's Association. “These types of changes matter for individuals and for their families.”

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. It does not halt or reverse the disease, and people do not get better. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world. It has “a rather small effect,” wrote NIH Alzheimer’s researcher Madhav Thambisetty, MD, PhD, in an email to Leaps.org. “It is unclear how meaningful this difference will be to patients, and it is unlikely that this level of difference will be obvious to a patient (or their caregivers).” Another issue is cost: Leqembi will become available to patients later this month, but Eisai is setting the price at $26,500 per year, meaning that very few patients will be able to afford it unless Medicare chooses to reimburse them for it.

The same side effects that plagued Aduhelm are common in Leqembi treatment as well. In many patients, amyloid doesn’t just accumulate around neurons, it also forms deposits in the walls of blood vessels. Blood vessels that are shot through with amyloid are more brittle. If you infuse a drug that targets amyloid, brittle blood vessels in the brain can develop leakage that results in swelling or bleeds. Most of these come with no symptoms, and are only seen during testing, which is why they are called “imaging abnormalities.” But in situations where patients have multiple diseases or are prescribed incompatible drugs, they can be serious enough to cause death. The three deaths reported from Leqembi treatment (so far) are enough to make Thambisetty wonder “how well the drug may be tolerated in real world clinical practice where patients are likely to be sicker and have multiple other medical conditions in contrast to carefully selected patients in clinical trials.”

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval.

Still, there are reasons to be excited. A successful Alzheimer’s drug can pave the way for combination studies, in which patients try a known effective drug alongside newer, more experimental ones; or preventative studies, which take place years before symptoms occur. It also represents enormous strides in researchers’ understanding of the disease. For example, drug dosages have increased massively—in some cases quadrupling—from the early days of Alzheimer’s research. And patient selection for studies has changed drastically as well. Doctors now know that you’ve got to catch the disease early, through PET-scans or CSF tests for amyloid, if you want any chance of changing its course.

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval. His lab already uses blood tests for different types of amyloid, for different types of tau, and for measures of neuroinflammation, neural damage, and synaptic health, but commercially available versions from companies like C2N, Quest, and Fuji Rebio are likely to hit the market in the next couple of years. “[They are] going to transform the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease,” Porsteinsson says. “If someone is experiencing memory problems, their physicians will be able to order a blood test that will tell us if this is the result of changes in your brain due to Alzheimer's disease. It will ultimately make it much easier to identify people at a very early stage of the disease, where they are most likely to benefit from treatment.”

Learn more about new blood tests to detect Alzheimer's

Early detection can help patients for more philosophical reasons as well. Betsy Groves credits finding her Alzheimer’s early with giving her the space to understand and process the changes that were happening to her before they got so bad that she couldn’t. She has been able to update her legal documents and, through her role on the Advisory Group, help the Alzheimer’s Association with developing its programs and support services for people in the early stages of the disease. She still drives, and because she and her husband love to travel, they are hoping to get out of grey, rainy Cambridge and off to Texas or Arizona this spring.

Because her Alzheimer’s disease involves amyloid deposits (a “substantial portion” do not, says Claire Sexton, which is an additional complication for research), and has not yet reached an advanced stage, Groves may be a good candidate to try Leqembi. She says she’d welcome the opportunity to take it. If she can get access, Groves hopes the drug will give her more days to be fully functioning with her husband, daughters, and three grandchildren. Mostly, she avoids thinking about what the latter stages of Alzheimer’s might be like, but she knows the time will come when it will be her reality. “So whatever lecanemab can do to extend my more productive ways of engaging with relationships in the world,” she says. “I'll take that in a minute.”

A New Test Aims to Objectively Measure Pain. It Could Help Legitimate Sufferers Access the Meds They Need.

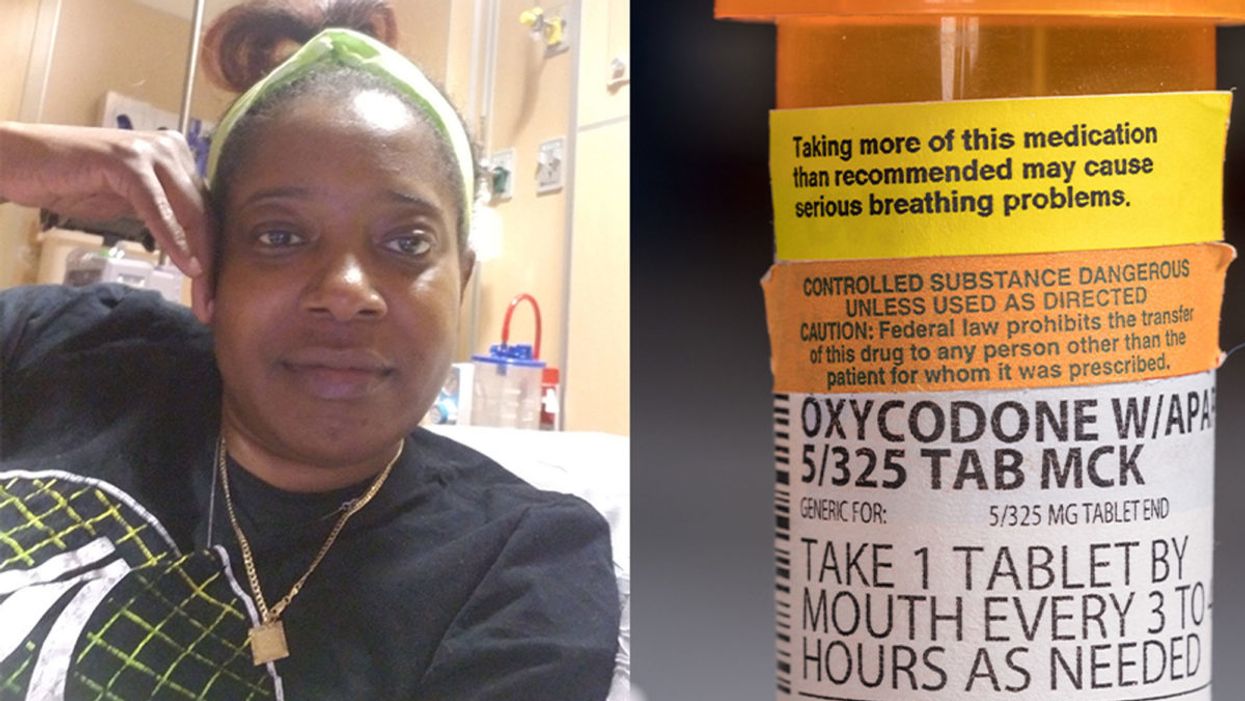

Sickle cell patient Bridgett Willkie found herself being labeled an addict when she sought an opioid prescription to control her pain.

"That throbbing you feel for the first minute after a door slams on your finger."

This is how Central Florida resident Bridgett Willkie describes the attacks of pain caused by her sickle cell anemia – a genetic blood disorder in which a patient's red blood cells become shaped like sickles and get stuck in blood vessels, thereby obstructing the flow of blood and oxygen.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was."

Willkie's lifelong battle with the condition has led to avascular necrosis in both of her shoulders, hips, knees and ankles. This means that her bone tissue is dying due to insufficient blood supply (sickle cell anemia is among the medical conditions that can decrease blood flow to one's bones).

"That adds to the pain significantly," she says. "Every time my heart beats, it hurts. And the pain moves. It follows the path of circulation. I liken it to a traffic jam in my veins."

For more than a decade, she received prescriptions for Oxycontin. Then, four years ago, her hematologist – who had been her doctor for 18 years – suffered a fatal heart attack. She says her longtime doctor's replacement lacked experience treating sickle cell patients and was uncomfortable writing her a prescription for opioids. What's more, this new doctor wanted to place her in a drug rehab facility.

"Because I refused to go, he stopped writing my scripts," she says. The ensuing three months were spent at home, detoxing. She describes the pain as unbearable. "Sometimes I just wanted to die."

One of the effects of the opioid epidemic is that many legitimate pain patients have seen their opioids significantly reduced or downright discontinued because of their doctors' fears of over-prescribing addictive medications.

"I found myself being labeled as an addict and I never was...Being treated like a drug-seeking patient is degrading and humiliating," says Willkie, who adds that when she is at the hospital, "it's exhausting arguing with the doctors...You dread them making their rounds because every day they come in talking about weaning you off your meds."

Situations such as these are fraught with tension between patients and doctors, who must remain wary about the risk of over-prescribing powerful and addictive medications. Adding to the complexity is that it can be very difficult to reliably assess a patient's level of physical pain.

However, this difficulty may soon decline, as Indiana University School of Medicine researchers, led by Dr. Alexander B. Niculescu, have reportedly devised a way to objectively assess physical pain by analyzing biomarkers in a patient's blood sample. The results of a study involving more than 300 participants were published earlier this year in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Niculescu – who is both a professor of psychiatry and medical neuroscience at the IU School of Medicine – explains that, when someone is in severe physical pain, a blood sample will show biomarkers related to intracellular adhesion and cell-signaling mechanisms. He adds that some of these biomarkers "have prior convergent evidence from animal or human studies for involvement in pain."

Aside from reliably measuring pain severity, Niculescu says blood biomarkers can measure the degree of one's response to treatment and also assess the risk of future recurrences of pain. He believes this new method's greatest benefit, however, might be the ability to identify a number of non-opioid medications that a particular patient is likely to respond to, based on his or her biomarker profile.

Clearly, such a method could be a gamechanger for pain patients and the professionals who treat them. As of yet, health workers have been forced to make crucial decisions based on their clinical impressions of patients; such impressions are invariably subjective. A method that enables people to prove the extent of their pain could remove the stigma that many legitimate pain patients face when seeking to obtain their needed medicine. It would also improve their chances of receiving sufficient treatment.

Niculescu says it's "theoretically possible" that there are some conditions which, despite being severe, might not reveal themselves through his testing method. But he also says that, "even if the same molecular markers that are involved in the pain process are not reflected in the blood, there are other indirect markers that should reflect the distress."

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years.

Willkie says she would welcome a reliable pain assessment method. Well-aware that she is not alone in her plight, she has more than 500 Facebook friends with sickle cell disease, and she says that "all of their opioid meds have been restricted or cut" as a result of the opioid crisis. Some now feel compelled to find their opioids "on the streets." She says she personally has never obtained opioids this way. Instead, she relies on marijuana to mitigate her pain.

Niculescu expects his testing method will be available to the medical community at large within one to three years: "It takes a while for things to translate from a lab setting to a commercial testing arena."

In the meantime, for Willkie and other patients, "we have to convince doctors and nurses that we're in pain."

Some people can eat red meat without negative health consequences, which may be due to variability between people's gut microbes.

In different countries' national dietary guidelines, red meats (beef, pork, and lamb) are often confined to a very small corner. Swedish officials, for example, advise the population to "eat less red and processed meat". Experts in Greece recommend consuming no more than four servings of red meat — not per week, but per month.

"Humans 100% rely on the microbes to digest this food."

Yet somehow, the matter is far from settled. Quibbles over the scientific evidence emerge on a regular basis — as in a recent BMJ article titled, "No need to cut red meat, say new guidelines." News headlines lately have declared that limiting red meat may be "bad advice," while carnivore diet enthusiasts boast about the weight loss and good health they've achieved on an all-meat diet. The wildly successful plant-based burgers? To them, a gimmick. The burger wars are on.

Nutrition science would seem the best place to look for answers on the health effects of specific foods. And on one hand, the science is rather clear: in large populations, people who eat more red meat tend to have more health problems, including cardiovascular disease, colorectal cancer, and other conditions. But this sort of correlational evidence fails to settle the matter once and for all; many who look closely at these studies cite methodological shortcomings and a low certainty of evidence.

Some scientists, meanwhile, are trying to cut through the noise by increasing their focus on the mechanisms: exactly how red meat is digested and the step-by-step of how this affects human health. And curiously, as these lines of evidence emerge, several of them center around gut microbes as active participants in red meat's ultimate effects on human health.

Dr. Stanley Hazen, researcher and medical director of preventive cardiology at Cleveland Clinic, was one of the first to zero in on gut microorganisms as possible contributors to the health effects of red meat. In looking for chemical compounds in the blood that could predict the future development of cardiovascular disease, his lab identified a molecule called trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). Little by little, he and his colleagues began to gather both human and animal evidence that TMAO played a role in causing heart disease.

Naturally, they tried to figure out where the TMAO came from. Hazen says, "We found that animal products, and especially red meat, were a dietary source that, [along with] gut microbes, would generate this product that leads to heart disease development." They observed that the gut microbes were essential for making TMAO out of dietary compounds (like red meat) that contained its precursor, trimethylamine (TMA).

So in linking red meat to cardiovascular disease through TMAO, the surprising conclusion, says Hazen, was that, "Without a doubt, [the microbes] are the most important aspect of the whole pathway."

"I think it's just a matter of time [before] we will have therapeutic interventions that actually target our gut microbes, just like the way we take drugs that lower cholesterol levels."

Other researchers have taken an interest in different red-meat-associated health problems, like colorectal cancer and the inflammation that accompanies it. This was the mechanistic link tackled by the lab of professor Karsten Zengler of the UC San Diego Departments of Pediatrics and Bioengineering—and it also led straight back to the gut microbes.

Zengler and colleagues recently published a paper in Nature Microbiology that focused on the effects of a red meat carbohydrate (or sugar) called Neu5Gc.

He explains, "If you eat animal proteins in your diet… the bound sugars in your diet are cleaved off in your gut and they get recycled. Your own cells will not recognize between the foreign sugars and your own sugars, because they look almost identical." The unsuspecting human cells then take up these foreign sugars — spurring antibody production and creating inflammation.

Zengler showed, however, that gut bacteria use enzymes to cleave off the sugar during digestion, stopping the inflammation and rendering the sugar harmless. "There's no enzyme in the human body that can cleave this [sugar] off. Humans 100% rely on the microbes to digest this food," he says.

Both researchers are quick to caution that the health effects of diet are complex. Other work indicates, for example, that while intake of red meat can affect TMAO levels, so can intake of fish and seafood. But these new lines of evidence could help explain why some people, ironically, seem to be in perfect health despite eating a lot of red meat: their ideal frequency of meat consumption may depend on their existing community of gut microbes.

"It helps explain what accounts for inter-person variability," Hazen says.

These emerging mechanisms reinforce overall why it's prudent to limit red meat, just as the nutritional guidelines advised in the first place. But both Hazen and Zengler predict that interventions to buffer the effects of too many ribeyes may be just around the corner.

Zengler says, "Our idea is that you basically can help your own digestive system detoxify these inflammatory compounds in meat, if you continue eating red meat or you want to eat a high amount of red meat." A possibly strategy, he says, is to use specific pre- or probiotics to cultivate an inflammation-reducing gut microbial community.

Hazen foresees the emergence of drugs that act not on the human, but on the human's gut microorganisms. "I think it's just a matter of time [before] we will have therapeutic interventions that actually target our gut microbes, just like the way we take drugs that lower cholesterol levels."

He adds, "It's a matter of 'stay tuned', I think."