How Leqembi became the biggest news in Alzheimer’s disease in 40 years, and what comes next

Betsy Groves, 73, with her granddaughter. Groves learned in 2021 that she has Alzheimer's disease. She hopes to take Leqembi, a drug approved by the FDA last week.

A few months ago, Betsy Groves traveled less than a mile from her home in Cambridge, Mass. to give a talk to a bunch of scientists. The scientists, who worked for the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai, wanted to know how she lived her life, how she thought about her future, and what it was like when a doctor’s appointment in 2021 gave her the worst possible news. Groves, 73, has Alzheimer’s disease. She caught it early, through a lumbar puncture that showed evidence of amyloid, an Alzheimer’s hallmark, in her cerebrospinal fluid. As a way of dealing with her diagnosis, she joined the Alzheimer’s Association’s National Early-Stage Advisory Board, which helped her shift into seeing her diagnosis as something she could use to help others.

After her talk, Groves stayed for lunch with the scientists, who were eager to put a face to their work. Biogen and Eisai were about to release the first drug to successfully combat Alzheimer’s in 40 years of experimental disaster. Their drug, which is known by the scientific name lecanemab and the marketing name Leqembi, was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last Friday, Jan. 6, after a study in 1,800 people showed that it reduced cognitive decline by 27 percent over 18 months.

It is no exaggeration to say that this result is a huge deal. The field of Alzheimer’s drug development has been absolutely littered with failures. Almost everything researchers have tried has tanked in clinical trials. “Most of the things that we've done have proven not to be effective, and it's not because we haven’t been taking a ton of shots at goal,” says Anton Porsteinsson, director of the University of Rochester Alzheimer's Disease Care, Research, and Education Program, who worked on the lecanemab trial. “I think it's fair to say you don't survive in this field unless you're an eternal optimist.”

As far back as 1984, a cure looked like it was within reach: Scientists discovered that the sticky plaques that develop in the brains of those who have Alzheimer’s are made up of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. Buildup of beta-amyloid seemed to be sufficient to disrupt communication between, and eventually kill, memory cells. If that was true, then the cure should be straightforward: Stop the buildup of beta-amyloid; stop the Alzheimer’s disease.

It wasn’t so simple. Over the next 38 years, hundreds of drugs designed either to interfere with the production of abnormal amyloid or to clear it from the brain flamed out in trials. It got so bad that neuroscience drug divisions at major pharmaceutical companies (AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, GSK, Amgen) closed one by one, leaving the field to smaller, scrappier companies, like Cambridge-based Biogen and Tokyo-based Eisai. Some scientists began to dismiss the amyloid hypothesis altogether: If this protein fragment was so important to the disease, why didn’t ridding the brain of it do anything for patients? There was another abnormal protein that showed up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, called tau. Some researchers defected to the tau camp, or came to believe the proteins caused damage in combination.

The situation came to a head in 2021, when the FDA granted provisional approval to a drug called aducanumab, marketed as Aduhelm, against the advice of its own advisory council. The approval was based on proof that Aduhelm reduced beta-amyloid in the brain, even though one research trial showed it had no effect on people’s symptoms or daily life. Aduhelm could also cause serious side effects, like brain swelling and amyloid related imaging abnormalities (known as ARIA, these are basically micro-bleeds that appear on MRI scans). Without a clear benefit to memory loss that would make these risks worth it, Medicare refused to pay for Aduhelm among the general population. Two congressional committees launched an investigation into the drug’s approval, citing corporate greed, lapses in protocol, and an unjustifiably high price. (Aduhelm was also produced by the pharmaceutical company Biogen.)

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world.

So far, Leqembi is like Aduhelm in that it has been given accelerated approval only for its ability to remove amyloid from the brain. Both are monoclonal antibodies that direct the immune system to attack and clear dysfunctional beta-amyloid. The difference is that, while that’s all Aduhelm was ever shown to do, Leqembi’s makers have already asked the FDA to give it full approval – a decision that would increase the likelihood that Medicare will cover it – based on data that show it also improves Alzheimer’s sufferer’s lives. Leqembi targets a different type of amyloid, a soluble version called “protofibrils,” and that appears to change the effect. “It can give individuals and their families three, six months longer to be participating in daily life and living independently,” says Claire Sexton, PhD, senior director of scientific programs & outreach for the Alzheimer's Association. “These types of changes matter for individuals and for their families.”

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. It does not halt or reverse the disease, and people do not get better. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world. It has “a rather small effect,” wrote NIH Alzheimer’s researcher Madhav Thambisetty, MD, PhD, in an email to Leaps.org. “It is unclear how meaningful this difference will be to patients, and it is unlikely that this level of difference will be obvious to a patient (or their caregivers).” Another issue is cost: Leqembi will become available to patients later this month, but Eisai is setting the price at $26,500 per year, meaning that very few patients will be able to afford it unless Medicare chooses to reimburse them for it.

The same side effects that plagued Aduhelm are common in Leqembi treatment as well. In many patients, amyloid doesn’t just accumulate around neurons, it also forms deposits in the walls of blood vessels. Blood vessels that are shot through with amyloid are more brittle. If you infuse a drug that targets amyloid, brittle blood vessels in the brain can develop leakage that results in swelling or bleeds. Most of these come with no symptoms, and are only seen during testing, which is why they are called “imaging abnormalities.” But in situations where patients have multiple diseases or are prescribed incompatible drugs, they can be serious enough to cause death. The three deaths reported from Leqembi treatment (so far) are enough to make Thambisetty wonder “how well the drug may be tolerated in real world clinical practice where patients are likely to be sicker and have multiple other medical conditions in contrast to carefully selected patients in clinical trials.”

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval.

Still, there are reasons to be excited. A successful Alzheimer’s drug can pave the way for combination studies, in which patients try a known effective drug alongside newer, more experimental ones; or preventative studies, which take place years before symptoms occur. It also represents enormous strides in researchers’ understanding of the disease. For example, drug dosages have increased massively—in some cases quadrupling—from the early days of Alzheimer’s research. And patient selection for studies has changed drastically as well. Doctors now know that you’ve got to catch the disease early, through PET-scans or CSF tests for amyloid, if you want any chance of changing its course.

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval. His lab already uses blood tests for different types of amyloid, for different types of tau, and for measures of neuroinflammation, neural damage, and synaptic health, but commercially available versions from companies like C2N, Quest, and Fuji Rebio are likely to hit the market in the next couple of years. “[They are] going to transform the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease,” Porsteinsson says. “If someone is experiencing memory problems, their physicians will be able to order a blood test that will tell us if this is the result of changes in your brain due to Alzheimer's disease. It will ultimately make it much easier to identify people at a very early stage of the disease, where they are most likely to benefit from treatment.”

Learn more about new blood tests to detect Alzheimer's

Early detection can help patients for more philosophical reasons as well. Betsy Groves credits finding her Alzheimer’s early with giving her the space to understand and process the changes that were happening to her before they got so bad that she couldn’t. She has been able to update her legal documents and, through her role on the Advisory Group, help the Alzheimer’s Association with developing its programs and support services for people in the early stages of the disease. She still drives, and because she and her husband love to travel, they are hoping to get out of grey, rainy Cambridge and off to Texas or Arizona this spring.

Because her Alzheimer’s disease involves amyloid deposits (a “substantial portion” do not, says Claire Sexton, which is an additional complication for research), and has not yet reached an advanced stage, Groves may be a good candidate to try Leqembi. She says she’d welcome the opportunity to take it. If she can get access, Groves hopes the drug will give her more days to be fully functioning with her husband, daughters, and three grandchildren. Mostly, she avoids thinking about what the latter stages of Alzheimer’s might be like, but she knows the time will come when it will be her reality. “So whatever lecanemab can do to extend my more productive ways of engaging with relationships in the world,” she says. “I'll take that in a minute.”

A Futuristic Suicide Machine Aims to End the Stigma of Assisted Dying

A prototype of the Sarco is currently on display at Venice Design.

Bob Dent ended his life in Perth, Australia in 1996 after multiple surgeries to treat terminal prostate cancer had left him mostly bedridden and in agony.

Although Dent and his immediate family believed it was the right thing to do, the physician who assisted in his suicide – and had pushed for Australia's Northern Territory to legalize the practice the prior year – was deeply shaken.

"You climb in, you are going somewhere, you are leaving, and you are saying goodbye."

"When you get to know someone pretty well, and they set a date to have lunch with you and then have them die at 2 p.m., it's hard to forget," recalls Philip Nitschke.

Nitschke remembers being highly anxious that the device he designed – which released a fatal dose of Nembutal into a patient's bloodstream after they answered a series of questions on a laptop computer to confirm consent – wouldn't work. He was so alarmed by the prospect he recalls his shirt being soaked through with perspiration.

Known as a "Deliverance Machine," it was comprised of the computer, attached by a sheet of wiring to an attache case containing an apparatus for delivering the Nembutal. Although gray, squat and grimly businesslike, it was vastly more sophisticated than Jack Kevorkian's Thanatron – a tangle of tubes, hooks and vials redolent of frontier dentistry.

The Deliverance Machine did work – for Dent and three other patients of Nitschke. However, it remained far from reassuring. "It's not a very comfortable feeling, having a little suitcase and going around to people," he says. "I felt a little like an executioner."

The furor caused in part by Nitschke's work led to Australia's federal government banning physician-assisted suicide in 1997. Nitschke went on to co-found Exit International, one of the foremost assisted suicide advocacy groups, and relocated to the Netherlands.

Exit International recently introduced its most ambitious initiative to date. It's called the Sarco — essentially the Eames lounger of suicide machines. A prototype is currently on display at Venice Design, an adjunct to the Biennale.

Sheathed in a soothing blue coating, the Sarco prototype contains a window and pivots on a pedestal to allow viewing by friends and family. Its close quarters means the opening of a small canister of liquid nitrogen would cause quick and painless asphyxiation. Patrons with second thoughts can press a button to cancel the process.

"The sleek and colorful death-pod looks like it is about to whisk you away to a new territory, or that it just landed after being launched from a Star Trek federation ship," says Charles C. Camosy, associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University in New York City, in an email. Camosy, who has profound misgivings about such a device, was not being complimentary.

Nitschke's goal is to de-medicalize assisted suicide, as liquid nitrogen is readily available. But he suggests employing a futuristic design will also move debate on the issue forward.

"You pick the time...have the party and people come around. You climb in, you are going somewhere, you are leaving, and you are saying goodbye," he says. "It lends itself to a sense of occasion."

Assisted suicide is spreading in developed countries, but very slowly. It was legalized again in Australia just last June, but only in one of its six states. It is legal throughout Canada and in nine U.S. states.

Although the process is outlawed throughout much of Europe, nations permitting it have taken a liberal approach. Euthanasia — where death may be instigated by an assenting physician at a patient's request — is legal in both Belgium and the Netherlands. A terminal illness is not required; a severe disability or a condition causing profound misery may suffice.

Only Switzerland permits suicide with non-physician assistance regardless of an individual's medical condition. David Goodall, a 104-year Australian scientist, traveled 8,000 miles to Basel last year to die with Exit International's assistance. Goodall was in good health for his age and his mind was needle sharp; at a news conference the day before he passed, he thoughtfully answered questions and sang Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" from memory. He simply believed he had lived long enough and wanted to avoid a diminishing quality of life.

"Dying is not a medical process, and if you've decided to do this through rational [decision-making], you should not have to get permission from the medical profession," Nitschke says.

However, the deathstyle aspirations of the Sarco bely the fact obtaining one will not be as simple as swiping a credit card. To create a legal firewall, anyone wishing to obtain a Sarco would have to purchase the plans, print the device themselves — it requires a high-end industrial printer to do so — then assemble it. As with the Deliverance device, the end user must be able to answer computer-generated questions designed by a Swiss psychiatrist to determine if they are making a rational decision. The process concludes with the transmission of a four-digit code to make the Sarco operational.

As with many cutting-edge designs, the path to a working prototype has been nettlesome. Plans for a printed window have been abandoned. How it will be obtained by end users remains unclear. There have also been complications in creating an AI-based algorithm underlying the user questions to reliably determine if the individual is of sound mind.

While Nitschke believes the Sarco will be deployed in Switzerland for the first time sometime next year, it will almost certainly be a subject of immense controversy. The Hastings Center, one of the world's major bioethics organizations and a leader on end-of-life decision-making, flatly refused to comment on the Sarco.

Camosy strongly condemns it. He notes since U.S. life expectancy is actually shortening — with despair-driven suicide playing a role — efforts must be marshaled to mitigate the trend. To him, the Sarco sends an utterly wrong message.

"It is diabolical that we would create machines to make it easier for people to kill themselves."

"Most people who request help in killing themselves don't do so because they are in intense, unbearable pain," he observes. "They do it because the culture in which they live has made them feel like a burden. This culture has told them they only have value if they are able to be 'productive' and 'contribute to society.'" He adds that the large majority of disability activists have been against assisted suicide and euthanasia because it is imperative to their movement that a stigma remain in place.

"It is diabolical that we would create machines to make it easier for people to kill themselves," Camosy concludes. "And anyone with even a single progressive bone in their body should resist this disturbingly morbid profit-making venture with everything they have."

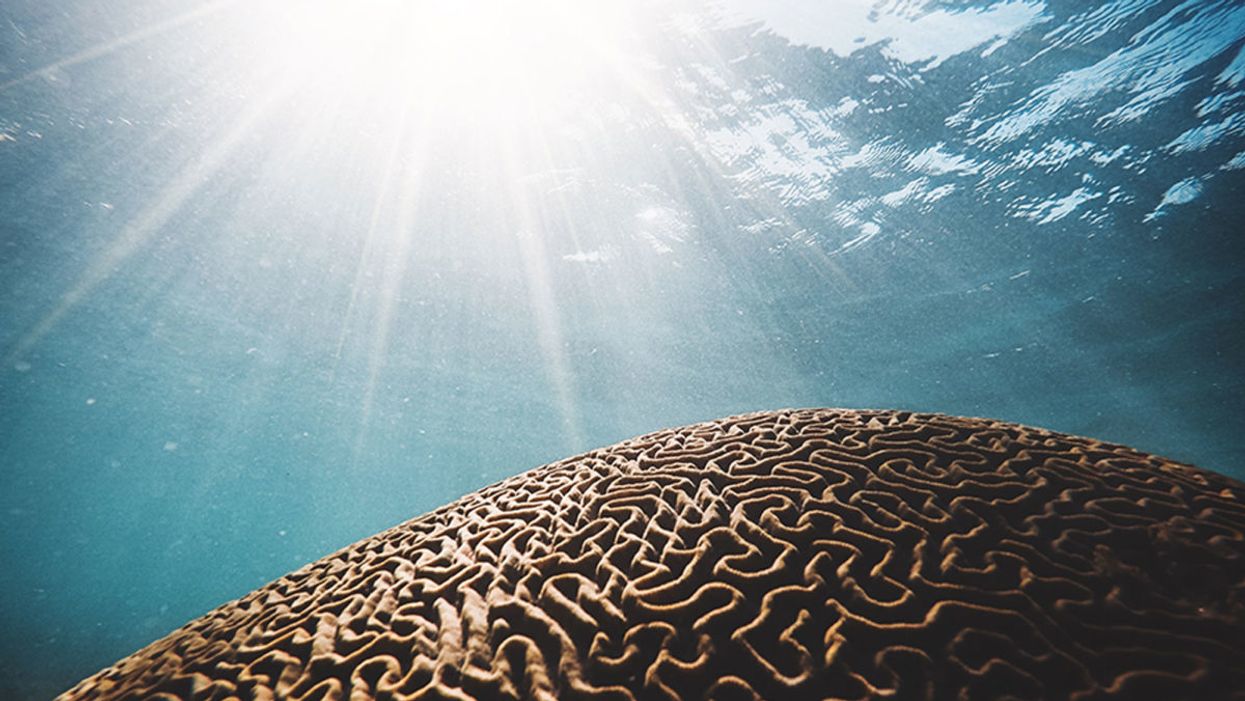

Biologists are Growing Mini-Brains. What If They Become Conscious?

Brain coral metaphorically represents the concept of growing organoids in a dish that may eventually attain consciousness--if scientists can first determine what that means.

Few images are more uncanny than that of a brain without a body, fully sentient but afloat in sterile isolation. Such specters have spooked the speculatively-minded since the seventeenth century, when René Descartes declared, "I think, therefore I am."

Since August 29, 2019, the prospect of a bodiless but functional brain has begun to seem far less fantastical.

In Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), the French penseur spins a chilling thought experiment: he imagines "having no hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses," but being tricked by a demon into believing he has all these things, and a world to go with them. A disembodied brain itself becomes a demon in the classic young-adult novel A Wrinkle in Time (1962), using mind control to subjugate a planet called Camazotz. In the sci-fi blockbuster The Matrix (1999), most of humanity endures something like Descartes' nightmare—kept in womblike pods by their computer overlords, who fill the captives' brains with a synthetized reality while tapping their metabolic energy as a power source.

Since August 29, 2019, however, the prospect of a bodiless but functional brain has begun to seem far less fantastical. On that date, researchers at the University of California, San Diego published a study in the journal Cell Stem Cell, reporting the detection of brainwaves in cerebral organoids—pea-size "mini-brains" grown in the lab. Such organoids had emitted random electrical impulses in the past, but not these complex, synchronized oscillations. "There are some of my colleagues who say, 'No, these things will never be conscious,'" lead researcher Alysson Muotri, a Brazilian-born biologist, told The New York Times. "Now I'm not so sure."

Alysson Muotri has no qualms about his creations attaining consciousness as a side effect of advancing medical breakthroughs.

(Credit: ZELMAN STUDIOS)

Muotri's findings—and his avowed ambition to push them further—brought new urgency to simmering concerns over the implications of brain organoid research. "The closer we come to his goal," said Christof Koch, chief scientist and president of the Allen Brain Institute in Seattle, "the more likely we will get a brain that is capable of sentience and feeling pain, agony, and distress." At the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, researchers from the Green Neuroscience Laboratory in San Diego called for a partial moratorium, warning that the field was "perilously close to crossing this ethical Rubicon and may have already done so."

Yet experts are far from a consensus on whether brain organoids can become conscious, whether that development would necessarily be dreadful—or even how to tell if it has occurred.

So how worried do we need to be?

***

An organoid is a miniaturized, simplified version of an organ, cultured from various types of stem cells. Scientists first learned to make them in the 1980s, and have since turned out mini-hearts, lungs, kidneys, intestines, thyroids, and retinas, among other wonders. These creations can be used for everything from observation of basic biological processes to testing the effects of gene variants, pathogens, or medications. They enable researchers to run experiments that might be less accurate using animal models and unethical or impractical using actual humans. And because organoids are three-dimensional, they can yield insights into structural, developmental, and other matters that an ordinary cell culture could never provide.

In 2006, Japanese biologist Shinya Yamanaka developed a mix of proteins that turned skin cells into "pluripotent" stem cells, which could subsequently be transformed into neurons, muscle cells, or blood cells. (He later won a Nobel Prize for his efforts.) Developmental biologist Madeline Lancaster, then a post-doctoral student at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna, adapted that technique to grow the first brain organoids in 2013. Other researchers soon followed suit, cultivating specialized mini-brains to study disorders ranging from microcephaly to schizophrenia.

Muotri, now a youthful 45-year-old, was among the boldest of these pioneers. His team revealed the process by which Zika virus causes brain damage, and showed that sofosbuvir, a drug previously approved for hepatitis C, protected organoids from infection. He persuaded NASA to fly his organoids to the International Space Station, where they're being used to trace the impact of microgravity on neurodevelopment. He grew brain organoids using cells implanted with Neanderthal genes, and found that their wiring differed from organoids with modern DNA.

Like the latter experiment, Muotri's brainwave breakthrough emerged from a longtime obsession with neuroarchaeology. "I wanted to figure out how the human brain became unique," he told me in a phone interview. "Compared to other species, we are very social. So I looked for conditions where the social brain doesn't function well, and that led me to autism." He began investigating how gene variants associated with severe forms of the disorder affected neural networks in brain organoids.

Tinkering with chemical cocktails, Muotri and his colleagues were able to keep their organoids alive far longer than earlier versions, and to culture more diverse types of brain cells. One team member, Priscilla Negraes, devised a way to measure the mini-brains' electrical activity, by planting them in a tray lined with electrodes. By four months, the researchers found to their astonishment, normal organoids (but not those with an autism gene) emitted bursts of synchronized firing, separated by 20-second silences. At nine months, the organoids were producing up to 300,000 spikes per minute, across a range of frequencies.

He shared his vision for "brain farms," which would grow organoids en masse for drug development or tissue transplants.

When the team used an artificial intelligence system to compare these patterns with EEGs of gestating fetuses, the program found them to be nearly identical at each stage of development. As many scientists noted when the news broke, that didn't mean the organoids were conscious. (Their chaotic bursts bore little resemblance to the orderly rhythms of waking adult brains.) But to some observers, it suggested that they might be approaching the borderline.

***

Shortly after Muotri's team published their findings, I attended a conference at UCSD on the ethical questions they raised. The scientist, in jeans and a sky-blue shirt, spoke rhapsodically of brain organoids' potential to solve scientific mysteries and lead to new medical treatments. He showed video of a spider-like robot connected to an organoid through a computer interface. The machine responded to different brainwave patterns by walking or stopping—the first stage, Muotri hoped, in teaching organoids to communicate with the outside world. He described his plans to develop organoids with multiple brain regions, and to hook them up to retinal organoids so they could "see." He shared his vision for "brain farms," which would grow organoids en masse for drug development or tissue transplants.

Muotri holds a spider-like robot that can connect to an organoid through a computer interface.

(Credit: ROLAND LIZARONDO/KPBS)

Yet Muotri also stressed the current limitations of the technology. His organoids contain approximately 2 million neurons, compared to about 200 million in a rat's brain and 86 billion in an adult human's. They consist only of a cerebral cortex, and lack many of a real brain's cell types. Because researchers haven't yet found a way to give organoids blood vessels, moreover, nutrients can't penetrate their inner recesses—a severe constraint on their growth.

Another panelist strongly downplayed the imminence of any Rubicon. Patricia Churchland, an eminent philosopher of neuroscience, cited research suggesting that in mammals, networked connections between the cortex and the thalamus are a minimum requirement for consciousness. "It may be a blessing that you don't have the enabling conditions," she said, "because then you don't have the ethical issues."

Christof Koch, for his part, sounded much less apprehensive than the Times had made him seem. He noted that science lacks a definition of consciousness, beyond an organism's sense of its own existence—"the fact that it feels like something to be you or me." As to the competing notions of how the phenomenon arises, he explained, he prefers one known as Integrated Information Theory, developed by neuroscientist Giulio Tononi. IIT considers consciousness to be a quality intrinsic to systems that reach a certain level of complexity, integration, and causal power (the ability for present actions to determine future states). By that standard, Koch doubted that brain organoids had stepped over the threshold.

One way to tell, he said, might be to use the "zap and zip" test invented by Tononi and his colleague Marcello Massimini in the early 2000s to determine whether patients are conscious in the medical sense. This technique zaps the brain with a pulse of magnetic energy, using a coil held to the scalp. As loops of neural impulses cascade through the cerebral circuitry, an EEG records the firing patterns. In a waking brain, the feedback is highly complex—neither totally predictable nor totally random. In other states, such as sleep, coma, or anesthesia, the rhythms are simpler. Applying an algorithm commonly used for computer "zip" files, the researchers devised a scale that allowed them to correctly diagnose most patients who were minimally conscious or in a vegetative state.

If scientists could find a way to apply "zap and zip" to brain organoids, Koch ventured, it should be possible to rank their degree of awareness on a similar scale. And if it turned out that an organoid was conscious, he added, our ethical calculations should strive to minimize suffering, and avoid it where possible—just as we now do, or ought to, with animal subjects. (Muotri, I later learned, was already contemplating sensors that would signal when organoids were likely in distress.)

During the question-and-answer period, an audience member pressed Churchland about how her views might change if the "enabling conditions" for consciousness in brain organoids were to arise. "My feeling is, we'll answer that when we get there," she said. "That's an unsatisfying answer, but it's because I don't know. Maybe they're totally happy hanging out in a dish! Maybe that's the way to be."

***

Muotri himself admits to no qualms about his creations attaining consciousness, whether sooner or later. "I think we should try to replicate the model as close as possible to the human brain," he told me after the conference. "And if that involves having a human consciousness, we should go in that direction." Still, he said, if strong evidence of sentience does arise, "we should pause and discuss among ourselves what to do."

"The field is moving so rapidly, you blink your eyes and another advance has occurred."

Churchland figures it will be at least a decade before anyone reaches the crossroads. "That's partly because the thalamus has a very complex architecture," she said. It might be possible to mimic that architecture in the lab, she added, "but I tend to think it's not going to be a piece of cake."

If anything worries Churchland about brain organoids, in fact, it's that Muotri's visionary claims for their potential could set off a backlash among those who find them unacceptably spooky. "Alysson has done brilliant work, and he's wonderfully charismatic and charming," she said. "But then there's that guy back there who doesn't think it's exciting; he thinks you're the Devil incarnate. You're playing into the hands of people who are going to shut you down."

Koch, however, is more willing to indulge Muotri's dreams. "Ten years ago," he said, "nobody would have believed you can take a stem cell and get an entire retina out of it. It's absolutely frigging amazing. So who am I to say the same thing can't be true for the thalamus or the cortex? The field is moving so rapidly, you blink your eyes and another advance has occurred."

The point, he went on, is not to build a Cartesian thought experiment—or a Matrix-style dystopia—but to vanquish some of humankind's most terrifying foes. "You know, my dad passed away of Parkinson's. I had a twin daughter; she passed away of sudden death syndrome. One of my best friends killed herself; she was schizophrenic. We want to eliminate all these terrible things, and that requires experimentation. We just have to go into it with open eyes."