An Astounding Treatment at an Astounding Price: Who Gets to Benefit?

Tony and Kelly Mantoan, with their boys Teddy and Fulton, who both suffer from SMA, a genetic disorder that makes walking, swallowing, and breathing progressively difficult.

Kelly Mantoan was nursing her newborn son, Teddy, in the NICU in a Philadelphia hospital when her doctor came in and silently laid a hand on her shoulder. Immediately, Kelly knew what the gesture meant and started to sob: Teddy, like his one-year-old brother, Fulton, had just tested positive for a neuromuscular condition called spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).

The boys were 8 and 10 when Kelly heard about an experimental new treatment, still being tested in clinical trials, called Spinraza.

"We knew that [SMA] was a genetic disorder, and we knew that we had a 1 in 4 chance of Teddy having SMA," Mantoan recalls. But the idea of having two children with the same severe disability seemed too unfair for Kelly and her husband, Tony, to imagine. "We had lots of well-meaning friends tell us, well, God won't do this to you twice," she says. Except that He, or a cruel trick of nature, had.

In part, the boys' diagnoses were so devastating because there was little that could be done at the time, back in 2009 and 2010, when the boys were diagnosed. Affecting an estimated 1 in 11,000 babies, SMA is a degenerative disease in which the body is deficient in survival motor neuron (SMN) protein, thanks to a genetic mutation or absence of the body's SNM1 gene. So muscles that control voluntary movement – such as walking, breathing, and swallowing – weaken and eventually cease to function altogether.

Babies diagnosed with SMA Type 1 rarely live past toddlerhood, while people diagnosed with SMA Types 2, 3, and 4 can live into adulthood, usually with assistance like ventilators and feeding tubes. Shortly after birth, both Teddy Mantoan and his brother, Fulton, were diagnosed with SMA Type 2.

The boys were 8 and 10 when Kelly heard about an experimental new treatment, still being tested in clinical trials, called Spinraza. Up until then, physical therapy was the only sanctioned treatment for SMA, and Kelly enrolled both her boys in weekly sessions to preserve some of their muscle strength as the disease marched forward. But Spinraza – a grueling regimen of lumbar punctures and injections designed to stimulate a backup survival motor neuron gene to produce more SMN protein – offered new hope.

In clinical trials, after just a few doses of Spinraza, babies with SMA Type 1 began meeting normal developmental milestones – holding up their heads, rolling over, and sitting up. In other trials, Spinraza treatment delayed the need for permanent ventilation, while patients on the placebo arm continued to lose function, and several died. Spinraza was such a success, and so well tolerated among patients, that clinical trials ended early and the drug was fast-tracked for FDA approval in 2016. In January 2017, when Kelly got the call that Fulton and Teddy had been approved by the hospital to start Spinraza infusions, Kelly dropped to her knees in the middle of the kitchen and screamed.

Spinraza, manufactured by Biogen, has been hailed as revolutionary, but it's also not without drawbacks: Priced per injection, just one dose of Spinraza costs $125,000, making it one of the most expensive drugs on the global market. What's worse, treatment requires a "loading dose" of four injections over a four-week period, and then periodic injections every four months, indefinitely. For the first year of treatment, Spinraza treatment costs $750,000 – and then $375,000 for every year thereafter.

Last week, a competitive treatment for SMA Type 1 manufactured by Novartis burst onto the market. The new treatment, called Zolgensma, is a one-time gene therapy intended to be given to infants and is currently priced at $2.125 million, or $425,000 annually for five years, making it the most expensive drug in the world. Like Spinraza, Zolgensma is currently raising challenging questions about how insurers and government payers like Medicaid will be able to afford these treatments without bankrupting an already-strained health care system.

To Biogen's credit, the company provides financial aid for Spinraza patients with private insurance who pay co-pays for treatment, as well as for those who have been denied by Medicaid and Medicare. But getting insurance companies to agree to pay for Spinraza can often be an ordeal in itself. Although Fulton and Teddy Mantoan were approved for treatment over two years ago, a lengthy insurance battle delayed treatment for another eight months – time that, for some SMA patients, can mean a significant loss of muscular function.

Kelly didn't notice anything in either boy – positive or negative – for the first few months of Spinraza injections. But one day in November 2017, as Teddy was lowered off his school bus in his wheelchair, he turned to say goodbye to his friends and "dab," – a dance move where one's arms are extended briefly across the chest and in the air. Normally, Teddy would dab by throwing his arms up in the air with momentum, striking a pose quickly before they fell down limp at his sides. But that day, Teddy held his arms rigid in the air. His classmates, along with Kelly, were stunned. "Teddy, look at your arms!" Kelly remembers shrieking. "You're holding them up – you're dabbing!"

Teddy and Fulton Mantoan, who both suffer from spinal muscular atrophy, have seen life-changing results from Spinraza.

(Courtesy of Kelly Mantoan)

Not long after Teddy's dab, the Mantoans started seeing changes in Fulton as well. "With Fulton, we realized suddenly that he was no longer choking on his food during meals," Kelly said. "Almost every meal we'd have to stop and have him take a sip of water and make him slow down and take small bites so he wouldn't choke. But then we realized we hadn't had to do that in a long time. The nurses at school were like, 'it's not an issue anymore.'"

For the Mantoans, this was an enormous relief: Less choking meant less chance of aspiration pneumonia, a leading cause of death for people with SMA Types 1 and 2.

While Spinraza has been life-changing for the Mantoans, it remains painfully out of reach for many others. Thanks to Spinraza's enormous price tag, the threshold for who gets to use it is incredibly high: Adult and pediatric patients, particularly those with state-sponsored insurance, have reported multiple insurance denials, lengthy appeals processes, and endless bureaucracy from insurance and hospitals alike that stand in the way of treatment.

Kate Saldana, a 21-year-old woman with Type 2 SMA, is one of the many adult patients who have been lobbying for the drug. Saldana, who uses a ventilator 20 hours each day, says that Medicaid denied her Spinraza treatments because they mistakenly believed that she used a ventilator full-time. Saldana is currently in the process of appealing their decision, but knows she is fighting an uphill battle.

Kate Saldana, who suffers from Type 2 SMA, has been fighting unsuccessfully for Medicaid to cover Spinraza.

(Courtesy of Saldana)

"Originally, the treatments were studied and created for infants and children," Saldana said in an e-mail. "There is a plethora of data to support the effectiveness of Spinraza in those groups, but in adults it has not been studied as much. That makes it more difficult for insurance to approve it, because they are not sure if it will be as beneficial."

Saldana has been pursuing treatment unsuccessfully since last August – but others, like Kimberly Hill, a 32-year-old with SMA Type 2, have been waiting even longer. Hill, who lives in Oklahoma, has been fighting for treatment since Spinraza went on the U.S. market in December 2016. Because her mobility is limited to the use of her left thumb, Hill is eager to try anything that will enable her to keep working and finish a Master's degree in Fire and Emergency Management.

"Obviously, my family and I were elated with the approval of Spinraza," Hill said in an e-mail. "We thought I would finally have the chance to get a little stronger and healthier." But with Medicare and Medicaid, coverage and eligibility varies wildly by state. Earlier this year, Medicaid approved Spinraza for adult patients only if a clawback clause was attached to the approval, meaning that under certain conditions the Medicaid funds would need to be paid back. Because of the clawback clause, hospitals have been reluctant to take on Spinraza treatments, effectively barring adult Medicaid patients from accessing the drug altogether.

Hill's hospital is currently in negotiations with Medicaid to move forward with Spinraza treatment, but in the meantime, Hill is in limbo. "We keep being told there is nothing we can do, and we are devastated," Hill said.

"I felt extremely sad and honestly a bit forgotten, like adults [with SMA] don't matter."

Between Spinraza and its new competitor, Zolgensma, some are speculating that insurers will start to favor Zolgensma coverage instead, since the treatment is shorter and ultimately cheaper than Spinraza in the long term. But for some adults with SMA who can't access Spinraza and who don't qualify for Zolgensma treatment, the issue of what insurers will cover is moot.

"I was so excited when I heard that Zolgensma was approved by the FDA," said Annie Wilson, an adult SMA patient from Alameda, Calif. who has been fighting for Spinraza since 2017. "When I became aware that it was only being offered to children, I felt extremely sad and honestly a bit forgotten, like adults [with SMA] don't matter."

According to information from a Biogen representative, more than 7500 people worldwide have been treated with Spinraza to date, one third of whom are adults.

While Spinraza has been revolutionary for thousands of patients, it's unclear how many more lives state agencies and insurance companies will allow it to save.

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

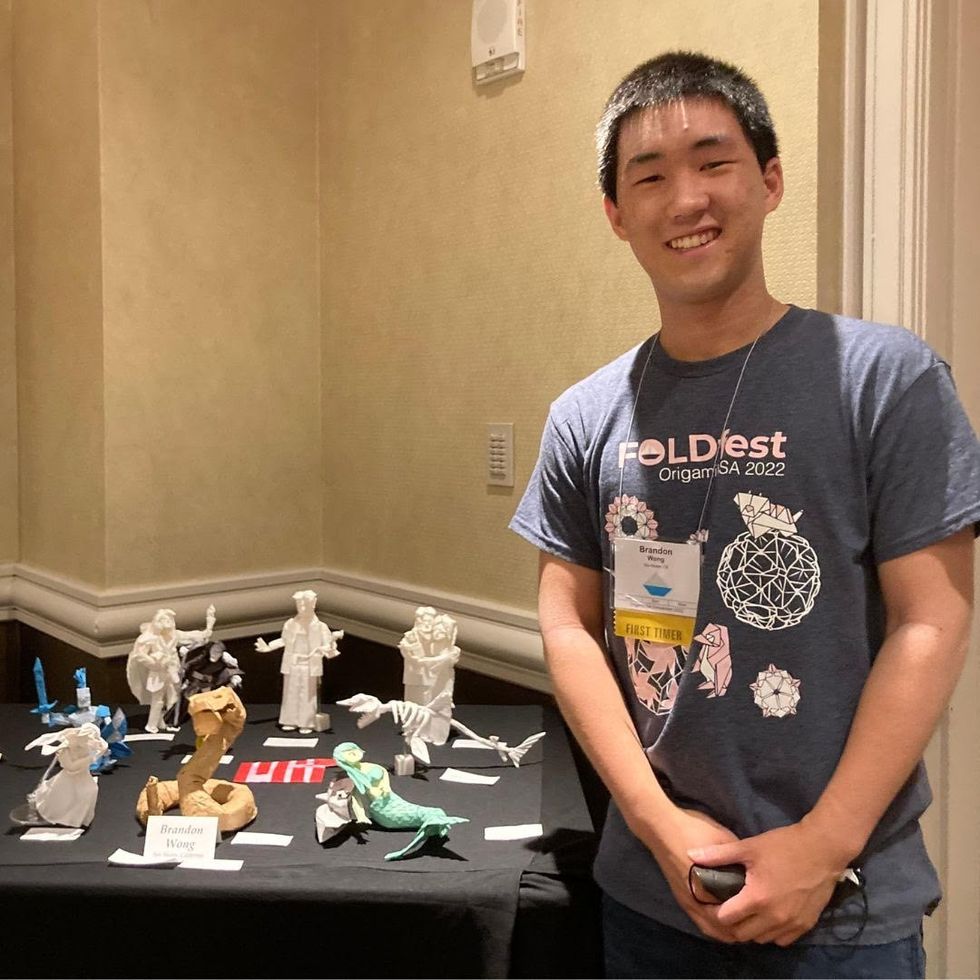

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”