Anti-Aging Pioneer Aubrey de Grey: “People in Middle Age Now Have a Fair Chance”

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Aubrey de Grey at the World Stem Cell Summit in Miami on January 25, 2018.

Aging is not a mystery, says famed researcher Dr. Aubrey de Grey, perhaps the world's foremost advocate of the provocative view that medical technology will one day allow humans to control the aging process and live healthily into our hundreds—or even thousands.

"The cultural attitudes toward all of this are going to be completely turned upside down by sufficiently promising results in the lab, in mice."

He likens aging to a car wearing down over time; as the body operates normally, it accumulates damage which can be tolerated for a while, but eventually sends us into steep decline. The most promising way to escape this biological reality, he says, is to repair the damage as needed with precise scientific tools.

The bad news is that doing this groundbreaking research takes a long time and a lot of money, which has not always been readily available, in part due to a cultural phenomenon he terms "the pro-aging trance." Cultural attitudes have long been fatalistic about the inevitability of aging; many people balk at the seemingly implausible prospect of indefinite longevity.

But the good news for de Grey—and those who are cheering him on—is that his view is becoming less radical these days. Both the academic and private sectors are racing to tackle aging; his own SENS Research Foundation, for one, has spun out into five different companies. Defeating aging, he says, "is not just a future industry; it's an industry now that will be both profitable and extremely good for your health."

De Grey sat down with Editor-in-Chief Kira Peikoff at the World Stem Cell Summit in Miami to give LeapsMag the latest scoop on his work. Here is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Since your book Ending Aging was published a decade ago, scientific breakthroughs in stem cell research, genome editing, and other fields have taken the world by storm. Which of these have most affected your research?

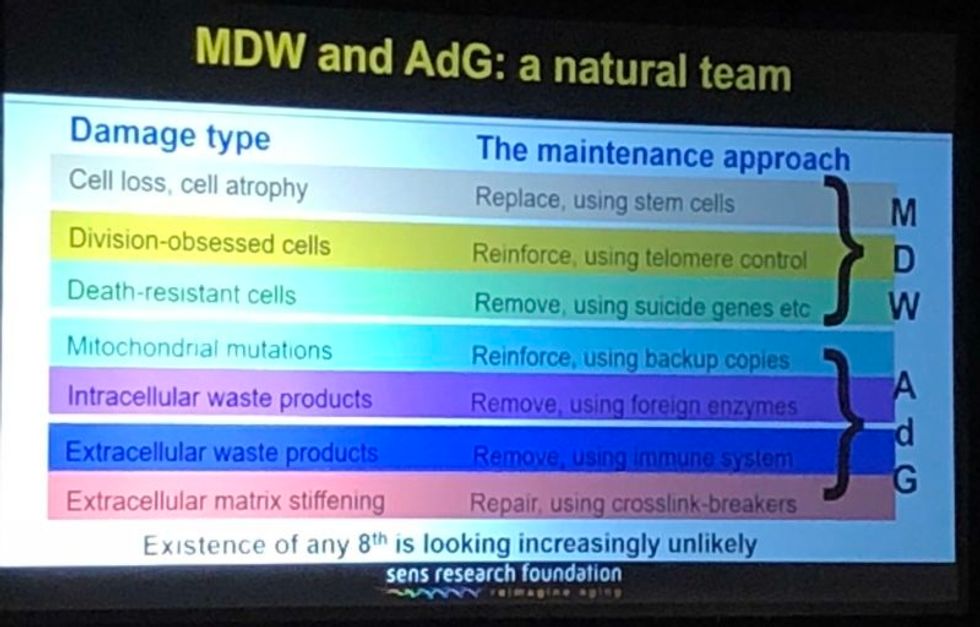

They have all affected it a lot in one way, and hardly at all in another way. They have speeded it up--facilitated short cuts, ways to get where we're already trying to go. What they have not done is identified any fundamental changes to the overall strategy. In the book, we described the seven major types of damage, and particular ways of going about fixing each of them, and that hasn't changed.

"Repair at the microscopic level, one would be able to expect to do without surgery, just by injecting the right kind of stem cells."

Has any breakthrough specifically made the biggest impact?

It's not just the obvious things, like iPS (induced pluripotent stem cells) and CRISPR (a precise tool for editing genes). It's also the more esoteric things that applied specifically to certain of our areas, but most people don't really know about them. For example, the identification of how to control something called co-translational mitochondrial protein import.

How much of the future of anti-aging treatments will involve regeneration of old tissue, or wholesale growth of new organs?

The more large-scale ones, regenerating whole new organs, are probably only going to play a role in the short-term and will be phased out relatively rapidly, simply because, in order to be useful, one has to employ surgery, which is really invasive. We'll want to try to get around that, but it seems quite likely that in the very early stages, the techniques we have for repairing things at the molecular and cellular level in situ will be insufficiently comprehensive, and so we will need to do the more sledgehammer approach of building a whole new organ and sticking it in.

Every time you are in a position where you're replacing an organ, you have the option, in principle, of repairing the organ, without replacing it. And repair at the microscopic level, one would be able to expect to do without surgery, just by injecting the right kind of stem cells or whatever. That would be something one would expect to be able to apply to someone much closer to death's door and much more safely in general, and probably much more cheaply. One would expect that subsequent generations of these therapies would move in that direction.

Your foundation is working on an initiative requiring $50 million in funding—

Well, if we had $50 million per year in funding, we could go about three times faster than we are on $5 million per year.

And you're looking at a 2021 timeframe to start human trials?

That's approximate. Remember, because we accumulate in the body so many different types of damage, that means we have many different types of therapy to repair that damage. And of course, each of those types has to be developed independently. It's very much a divide and conquer therapy. The therapies interact with each other to some extent; the repair of one type of damage may slow down the creation of another type of damage, but still that's how it's going to be.

And some of these therapies are much easier to implement than others. The easier components of what we need to do are already in clinical trials—stem cell therapies especially, and immunotherapy against amyloid in the brain, for example. Even in phase III clinical trials in some cases. So when I talk about a timeframe like 2021, or early 20s shall we say, I'm really talking about the most difficult components.

What recent strides are you most excited about?

Looking back over the past couple of years, I'm particularly proud of the successes we've had in the very most difficult areas. If you go through the 7 components of SENS, there are two that have absolutely been stuck in a rut and have gotten nowhere for 15 to 20 years, and we basically fixed that in both cases. We published two years ago in Science magazine that essentially showed a way forward against the stiffening of the extracellular matrix, which is responsible for things like wrinkles and hypertension. And then a year ago, we published a real breakthrough paper with regard to placing copies of the mitochondria DNA in the nuclear DNA modified in such a way that they still work, which is an idea that had been around for 30 years; everyone had given up on it, some a long time ago, and we basically revived it.

A slide presented by Aubrey de Grey, referencing his collaboration with Mike West at AgeX, showing the 7 types of damage that he believes must be repaired to end aging.

(Courtesy Kira Peikoff)

That's exciting. What do you think are the biggest barriers to defeating aging today: the technological challenges, the regulatory framework, the cost, or the cultural attitude of the "pro-aging" trance?

One can't really address those independently of each other. The technological side is one thing; it's hard, but we know where we're going, we've got a plan. The other ones are very intertwined with each other. A lot of people are inclined to say, the regulatory hurdle will be completely insurmountable, plus people don't recognize aging as a disease, so it's going to be a complete nonstarter. I think that's nonsense. And the reason is because the cultural attitudes toward all of this are going to be completely turned upside down before we have to worry about the regulatory hurdles. In other words, they're going to be turned upside down by sufficiently promising results in the lab, in mice. Once we get to be able to rejuvenate actually old mice really well so they live substantially longer than they otherwise would have done, in a healthy state, everyone's going to know about it and everyone's going to demand – it's not going to be possible to get re-elected unless you have a manifesto commitment to turn the FDA completely upside down and make sure this happens without any kind of regulatory obstacle.

I've been struggling away all these years trying to bring little bits of money in the door, and the reason I have is because of the skepticism as to regards whether this could actually work, combined with the pro-aging trance, which is a product of the skepticism – people not wanting to get their hopes up, so finding excuses about aging being a blessing in disguise, so they don't have to think about it. All of that will literally disintegrate pretty much overnight when we have the right kind of sufficiently impressive progress in the lab. Therefore, the availability of money will also [open up]. It's already cracking: we're already seeing the beginnings of the actual rejuvenation biotechnology industry that I've been talking about with a twinkle in my eye for some years.

"For humans, a 50-50 chance would be twenty years at this point, and there's a 10 percent chance that we won't get there for a hundred years."

Why do you think the culture is starting to shift?

There's no one thing yet. There will be that tipping point I mentioned, perhaps five years from now when we get a real breakthrough, decisive results in mice that make it simply impossible to carry on being fatalistic about all this. Prior to that, what we're already seeing is the impact of sheer old-school repeat advertising—me going out there, banging away and saying the same fucking thing again and again, and nobody saying anything that persuasively knocks me down. … And it's also the fact that we are making incremental amounts of progress, not just ourselves, but the scientific community generally. It has become incrementally more plausible that what I say might be true.

I'm sure you hate getting the timeline question, but if we're five years away from this breakthrough in mice, it's hard to resist asking—how far is that in terms of a human cure?

When I give any kind of timeframes, the only real care I have to take is to emphasize the variance. In this case I think we have got a 50-50 chance of getting to that tipping point in mice within five years from now, certainly it could be 10 or 15 years if we get unlucky. Similarly, for humans, a 50-50 chance would be twenty years at this point, and there's a 10 percent chance that we won't get there for a hundred years.

"I don't get people coming to me saying, well I don't think medicine for the elderly should be done because if it worked it would be a bad thing. People like to ignore this contradiction."

What would you tell skeptical people are the biggest benefits of a very long-lived population?

Any question about the longevity of people is the wrong question. Because the longevity that people fixate about so much will only ever occur as a side effect of health. However long ago you were born or however recently, if you're sick, you're likely to die fairly soon unless we can stop you being sick. Whereas if you're healthy, you're not. So if we do as well as we think we can do in terms of keeping people healthy and youthful however long ago they were born, then the side effect in terms of longevity and life expectancy is likely to be very large. But it's still a side effect, so the way that people actually ought to be—in fact have a requirement to be—thinking, is about whether they want people to be healthy.

Now I don't get people coming to me saying, well I don't think medicine for the elderly should be done because if it worked it would be a bad thing. People like to ignore this contradiction, they like to sweep it under the carpet and say, oh yeah, aging is totally a good thing.

People will never actually admit to the fact that what they are fundamentally saying is medicine for the elderly, if it actually works, would be bad, but still that is what they are saying.

Shifting gears a bit, I'm curious to find out which other radical visionaries in science and tech today you most admire?

Fair question. One is Mike West. I have the great privilege that I now work for him part-time with Age X. I have looked up to him very much for the past ten years, because what he did over the past 20 years starting with Geron is unimaginable today. He was working in an environment where I would not have dreamt of the possibility of getting any private money, any actual investment, in something that far out, that far ahead of its time, and he did it, again and again. It's insane what he managed to do.

What about someone like Elon Musk?

Sure, he's another one. He is totally impervious to the caution and criticism and conservatism that pervades humanity, and he's getting on making these bloody self-driving cars, space tourism, and so on, making them happen. He's thinking just the way I'm thinking really.

"You can just choose how frequently and how thoroughly you repair the damage. And you can make a different choice next time."

You famously said ten years ago that you think the first person to live to 1000 is already alive. Do you think that's still the case?

Definitely, yeah. I can't see how it could not be. Again, it's a probabilistic thing. I said there's at least a 10 percent chance that we won't get to what I call Longevity Escape Velocity for 100 years and if that's true, then the statement about 1000 years being alive already is not going to be the case. But for sure, I believe that the beneficiaries of what we may as well call SENS 1.0, the point where we get to LEV, those people are exceptionally unlikely ever to suffer from any kind of ill health correlated with their age. Because we will never fall below Longevity Escape Velocity once we attain it.

Could someone who was just born today expect—

I would say people in middle age now have a fair chance. Remember – a 50/50 chance of getting to LEV within 20 years, and when you get there, you don't just stay at biologically 70 or 80, you are rejuvenated back to biologically 30 or 40 and you stay there, so your risk of death each year is not related to how long ago you were born, it's the same as a young adult. Today, that's less than 1 in 1000 per year, and that number is going to go down as we get self-driving cars and all that, so actually 1000 is a very conservative number.

So you would be able to choose what age you wanted to go back to?

Oh sure, of course, it's just like a car. What you're doing is you're repairing damage, and the damage is still being created by the body's metabolism, so you can just choose how frequently and how thoroughly you repair the damage. And you can make a different choice next time.

What would be your perfect age?

I have no idea. That's something I don't have an opinion about, because I could change it whenever I like.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

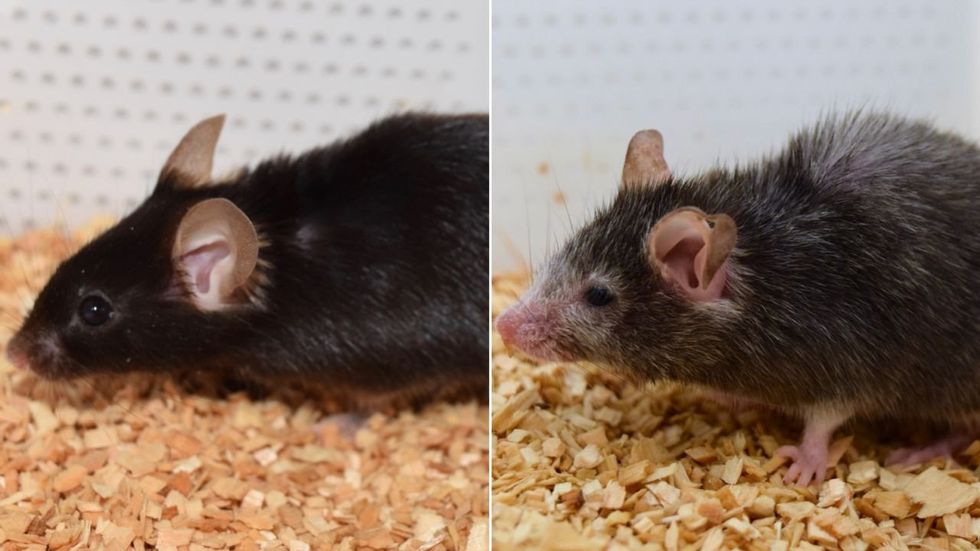

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School