Scientists redesign bacteria to tackle the antibiotic resistance crisis

Probiotic bacteria can be engineered to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs by releasing chemicals that kill them.

In 1945, almost two decades after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, he warned that as antibiotics use grows, they may lose their efficiency. He was prescient—the first case of penicillin resistance was reported two years later. Back then, not many people paid attention to Fleming’s warning. After all, the “golden era” of the antibiotics age had just began. By the 1950s, three new antibiotics derived from soil bacteria — streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline — could cure infectious diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, meningitis and typhoid fever, among others.

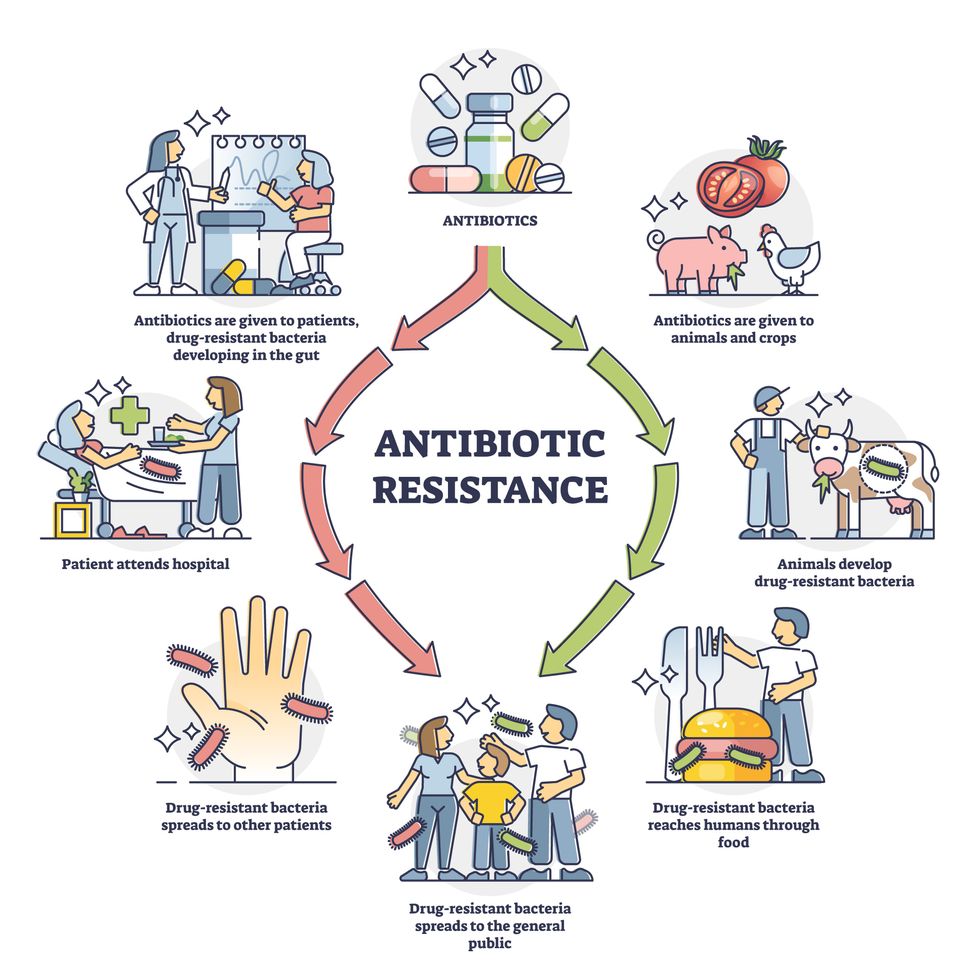

Today, these antibiotics and many of their successors developed through the 1980s are gradually losing their effectiveness. The extensive overuse and misuse of antibiotics led to the rise of drug resistance. The livestock sector buys around 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. every year. Farmers feed cows and chickens low doses of antibiotics to prevent infections and fatten up the animals, which eventually causes resistant bacterial strains to evolve. If manure from cattle is used on fields, the soil and vegetables can get contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Another major factor is doctors overprescribing antibiotics to humans, particularly in low-income countries. Between 2000 to 2018, the global rates of human antibiotic consumption shot up by 46 percent.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring a promising avenue: the use of synthetic biology to engineer new bacteria that may work better than antibiotics. The need continues to grow, as a Lancet study linked antibiotic resistance to over 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria. The western sub-Saharan Africa region had the highest death rate (27.3 people per 100,000).

Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

To make it worse, our remedy pipelines are drying up. Out of the 18 biggest pharmaceutical companies, 15 abandoned antibiotic development by 2013. According to the AMR Action Fund, venture capital has remained indifferent towards biotech start-ups developing new antibiotics. In 2019, at least two antibiotic start-ups filed for bankruptcy. As of December 2020, there were 43 new antibiotics in clinical development. But because they are based on previously known molecules, scientists say they are inadequate for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria. Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

The rise of synthetic biology

To circumvent this dire future, scientists have been working on alternative solutions using synthetic biology tools, meaning genetically modifying good bacteria to fight the bad ones.

From the time life evolved on earth around 3.8 billion years ago, bacteria have engaged in biological warfare. They constantly strategize new methods to combat each other by synthesizing toxic proteins that kill competition.

For example, Escherichia coli produces bacteriocins or toxins to kill other strains of E.coli that attempt to colonize the same habitat. Microbes like E.coli (which are not all pathogenic) are also naturally present in the human microbiome. The human microbiome harbors up to 100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells. The majority of them are beneficial organisms residing in the gut at different compositions.

The chemicals that these “good bacteria” produce do not pose any health risks to us, but can be toxic to other bacteria, particularly to human pathogens. For the last three decades, scientists have been manipulating bacteria’s biological warfare tactics to our collective advantage.

In the late 1990s, researchers drew inspiration from electrical and computing engineering principles that involve constructing digital circuits to control devices. In certain ways, every cell in living organisms works like a tiny computer. The cell receives messages in the form of biochemical molecules that cling on to its surface. Those messages get processed within the cells through a series of complex molecular interactions.

Synthetic biologists can harness these living cells’ information processing skills and use them to construct genetic circuits that perform specific instructions—for example, secrete a toxin that kills pathogenic bacteria. “Any synthetic genetic circuit is merely a piece of information that hangs around in the bacteria’s cytoplasm,” explains José Rubén Morones-Ramírez, a professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico. Then the ribosome, which synthesizes proteins in the cell, processes that new information, making the compounds scientists want bacteria to make. “The genetic circuit remains separated from the living cell’s DNA,” Morones-Ramírez explains. When the engineered bacteria replicates, the genetic circuit doesn’t become part of its genome.

Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut.

In 2000, Boston-based researchers constructed an E.coli with a genetic switch that toggled between turning genes on and off two. Later, they built some safety checks into their bacteria. “To prevent unintentional or deleterious consequences, in 2009, we built a safety switch in the engineered bacteria’s genetic circuit that gets triggered after it gets exposed to a pathogen," says James Collins, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and faculty member at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “After getting rid of the pathogen, the engineered bacteria is designed to switch off and leave the patient's body.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics causes resistant strains to evolve

Adobe Stock

Seek and destroy

As the field of synthetic biology developed, scientists began using engineered bacteria to tackle superbugs. They first focused on Vibrio cholerae, which in the 19th and 20th century caused cholera pandemics in India, China, the Middle East, Europe, and Americas. Like many other bacteria, V. cholerae communicate with each other via quorum sensing, a process in which the microorganisms release different signaling molecules, to convey messages to its brethren. Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut. When untreated, cholera has a mortality rate of 25 to 50 percent and outbreaks frequently occur in developing countries, especially during floods and droughts.

Sometimes, however, V. cholerae makes mistakes. In 2008, researchers at Cornell University observed that when quorum sensing V. cholerae accidentally released high concentrations of a signaling molecule called CAI-1, it had a counterproductive effect—the pathogen couldn’t colonize the gut.

So the group, led by John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering, developed a novel strategy to combat V. cholerae. They genetically engineered E.coli to eavesdrop on V. cholerae communication networks and equipped it with the ability to release the CAI-1 molecules. That interfered with V. cholerae progress. Two years later, the Cornell team showed that V. cholerae-infected mice treated with engineered E.coli had a 92 percent survival rate.

These findings inspired researchers to sic the good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi onto the drug-resistant ones.

Three years later in 2011, Singapore-based scientists engineered E.coli to detect and destroy Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an often drug-resistant pathogen that causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. Once the genetically engineered E.coli found its target through its quorum sensing molecules, it then released a peptide, that could eradicate 99 percent of P. aeruginosa cells in a test-tube experiment. The team outlined their work in a Molecular Systems Biology study.

“At the time, we knew that we were entering new, uncharted territory,” says lead author Matthew Chang, an associate professor and synthetic biologist at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the study. “To date, we are still in the process of trying to understand how long these microbes stay in our bodies and how they might continue to evolve.”

More teams followed the same path. In a 2013 study, MIT researchers also genetically engineered E.coli to detect P. aeruginosa via the pathogen’s quorum-sensing molecules. It then destroyed the pathogen by secreting a lab-made toxin.

Probiotics that fight

A year later in 2014, a Nature study found that the abundance of Ruminococcus obeum, a probiotic bacteria naturally occurring in the human microbiome, interrupts and reduces V.cholerae’s colonization— by detecting the pathogen’s quorum sensing molecules. The natural accumulation of R. obeum in Bangladeshi adults helped them recover from cholera despite living in an area with frequent outbreaks.

The findings from 2008 to 2014 inspired Collins and his team to delve into how good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi can attack drug-resistant bacteria. In 2018, Collins and his team developed the engineered probiotic strategy. They tweaked a bacteria commonly found in yogurt called Lactococcus lactis to treat cholera.

Engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut. --José Rubén Morones-Ramírez.

More scientists followed with more experiments. So far, researchers have engineered various probiotic organisms to fight pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (leading cause of skin, tissue, bone, joint and blood infections) and Clostridium perfringens (which causes watery diarrhea) in test-tube and animal experiments. In 2020, Russian scientists engineered a probiotic called Pichia pastoris to produce an enzyme called lysostaphin that eradicated S. aureus in vitro. Another 2020 study from China used an engineered probiotic bacteria Lactobacilli casei as a vaccine to prevent C. perfringens infection in rabbits.

In a study last year, Ramírez’s group at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, engineered E. coli to detect quorum-sensing molecules from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA, a notorious superbug. The E. coli then releases a bacteriocin that kills MRSA. “An antibiotic is just a molecule that is not intelligent,” says Ramírez. “On the other hand, engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut.”

Collins and Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, found that engineered E. coli can help treat other conditions—such as phenylketonuria, a rare metabolic disorder, that causes the build-up of an amino acid phenylalanine. Their start-up Synlogic aims to commercialize the technology, and has completed a phase 2 clinical trial.

Circumventing the challenges

The bacteria-engineering technique is not without pitfalls. One major challenge is that beneficial gut bacteria produce their own quorum-sensing molecules that can be similar to those that pathogens secrete. If an engineered bacteria’s biosensor is not specific enough, it will be ineffective.

Another concern is whether engineered bacteria might mutate after entering the gut. “As with any technology, there are risks where bad actors could have the capability to engineer a microbe to act quite nastily,” says Collins of MIT. But Collins and Ramírez both insist that the chances of the engineered bacteria mutating on its own are virtually non-existent. “It is extremely unlikely for the engineered bacteria to mutate,” Ramírez says. “Coaxing a living cell to do anything on command is immensely challenging. Usually, the greater risk is that the engineered bacteria entirely lose its functionality.”

However, the biggest challenge is bringing the curative bacteria to consumers. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in antibiotics or their alternatives because it’s less profitable than developing new medicines for non-infectious diseases. Unlike the more chronic conditions like diabetes or cancer that require long-term medications, infectious diseases are usually treated much quicker. Running clinical trials are expensive and antibiotic-alternatives aren’t lucrative enough.

“Unfortunately, new medications for antibiotic resistant infections have been pushed to the bottom of the field,” says Lu of MIT. “It's not because the technology does not work. This is more of a market issue. Because clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the only solution is that governments will need to fund them.” Lu stresses that societies must lobby to change how the modern healthcare industry works. “The whole world needs better treatments for antibiotic resistance.”

New Options Are Emerging in the Search for Better Birth Control

A decade ago, Elizabeth Summers' options for birth control suddenly narrowed. Doctors diagnosed her with Factor V Leiden, a rare genetic disorder, after discovering blood clots in her lungs. The condition increases the risk of clotting, so physicians told Summers to stay away from the pill and other hormone-laden contraceptives. "Modern medicine has generally failed to provide me with an effective and convenient option," she says.

But new birth control options are emerging for women like Summers. These alternatives promise to provide more choices to women who can't ingest hormones or don't want to suffer their unpleasant side effects.

These new products have their own pros and cons. Still, doctors are welcoming new contraceptives following a long drought in innovation. "It's been a long time since we've had something new in the world of contraception," says Heather Irobunda, an obstetrician and gynecologist at NYC Health and Hospitals.

On social media, Irobunda often fields questions about one of these new options, a lubricating gel called Phexxi. San Diego-based Evofem, the company behind Phexxi, has been advertising the product on Hulu and Instagram after the gel was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in May 2020. The company's trendy ads target women who feel like condoms diminish the mood, but who also don't want to mess with an IUD or hormones.

Here's how it works: Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex. The gel regulates vaginal pH — essentially, the acidity levels — in a range that's inhospitable to sperm. It sounds a lot like spermicide, which is also placed in the vagina prior to sex to prevent pregnancy. But spermicide can damage the vagina's cell walls, which can increase the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

"Not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option."

Phexxi isn't without side effects either. The most common one is vaginal burning, according to a late-stage trial. It's also possible to develop a urinary tract infection while using the product. That same study found that during typical use, Phexxi is about 86 percent effective at preventing pregnancy. The efficacy rate is comparable to condoms but lower than birth control pills (91 percent) and significantly lower than an IUD (99 percent).

Phexxi – which comes in a pack of 12 – represents a tiny but growing part of the birth control market. Pharmacies dispensed more than 14,800 packs from April through June this year, a 65 percent increase over the previous quarter, according to data from Evofem.

"We've been able to demonstrate that not only is innovation needed, but women want a non-hormonal option," says Saundra Pelletier, Evofem's CEO.

Beyond contraception, the company is carrying out late-stage tests to gauge Phexxi's effectiveness at preventing the sexually transmitted infections chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Phexxi is inserted via a tampon-like device up to an hour before sex.

Phexxi

A New Pill

The first birth control pill arrived in 1960, combining the hormones estrogen and progestin to stop sperm from joining with an egg, giving women control over their fertility. Subsequent formulations sought to ease side effects, by way of lower amounts of estrogen. But some women still experience headaches and nausea – or more serious complications like blood clots. On social media, women recently noted that birth control pills are much more likely to cause blood clots than Johnson & Johnson's COVID-19 vaccine that was briefly paused to evaluate the risk of clots in women under age 50. What will it take, they wondered, for safer birth control?

Mithra Pharmaceuticals of Belgium sought to create a gentler pill. In April, the FDA approved Mithra's Nextstellis, which includes a naturally occurring estrogen, the first new estrogen in the U.S. in 50 years. Nextstellis selectively acts on tissues lining the uterus, while other birth control pills have a broader target.

A Phase 3 trial showed a 98 percent efficacy rate. Andrew London, an obstetrician and gynecologist, who practices at several Maryland hospitals, says the results are in line with some other birth control pills. But, he added, early studies indicate that Nextstellis has a lower risk of blood clotting, along with other potential benefits, which additional clinical testing must confirm.

"It's not going to be worse than any other pill. We're hoping it's going to be significantly better," says London.

The estrogen in Nexstellis, called estetrol, was skipped over by the pharmaceutical industry after its discovery in the 1960s. Estetrol circulates between the mother and fetus during pregnancy. Decades later, researchers took a new look, after figuring out how to synthesize estetrol in a lab, as well as produce estetrol from plants.

"That allowed us to really start to investigate the properties and do all this stuff you have to do for any new drug," says Michele Gordon, vice president of marketing in women's health at Mayne Pharma, which licensed Nextstellis.

Bonnie Douglas, who followed the development of Nextstellis as part of a search for better birth control, recently switched to the product. "So far, it's much more tolerable," says Douglas. Previously, the Midwesterner was so desperate to find a contraceptive with fewer side effects that she turned to an online pharmacy to obtain a different birth control pill that had been approved in Canada but not in the U.S.

Contraceptive Access

Even if a contraceptive lands FDA approval, access poses a barrier. Getting insurers to cover new contraceptives can be difficult. For the uninsured, state and federal programs can help, and companies should keep prices in a reasonable range, while offering assistance programs. So says Kelly Blanchard, president of the nonprofit Ibis Reproductive Health. "For innovation to have impact, you want to reach as many folks as possible," she says.

In addition, companies developing new contraceptives have struggled to attract venture capital. That's changing, though.

In 2015, Sabrina Johnson founded DARÉ Bioscience around the idea of women's health. She estimated the company would be fully funded in six months, based on her track record in biotech and the demand for novel products.

But it's been difficult to get male investors interested in backing new contraceptives. It took Johnson two and a half years to raise the needed funds, via a reverse merger that took the company public. "There was so much education that was necessary," Johnson says, adding: "The landscape has changed considerably."

Johnson says she would like to think DARÉ had something to do with the shift, along with companies like Organon, a spinout of pharma company Merck that's focused on reproductive health. In surveying the fertility landscape, DARÉ saw limited non-hormonal options. On-demand options – like condoms – can detract from the moment. Copper IUDs must be inserted by a doctor and removed if a woman wants to return to fertility, and this method can have onerous side effects.

So, DARÉ created Ovaprene, a hormone-free device that's designed to be inserted into the vagina monthly by the user. The mesh product acts as a barrier, while releasing a chemical that immobilizes sperm. In an early study, the company reported that Ovaprene prevented almost all sperm from entering the cervical canal. The results, DARÉ believes, indicate high efficacy.

A late-stage study, slated to kick off next year, will be the true judge. Should Ovaprene eventually win regulatory approval, drug giant Bayer will handle commercializing the device.

Other new forms of birth control in development are further out, and that's assuming they perform well in clinical trials. Among them: a once-a-month birth control pill, along with a male version of the birth control pill. The latter is often brought up among women who say it's high time that men take a more proactive role in birth control.

For Summers, her search for a safe and convenient birth control continues. She tried Phexxi, which caused irritation. Still, she's excited that a non-hormonal option now exists. "I'm sure it will work for others," she says.

Scientists Are Growing an Edible Cholera Vaccine in Rice

The world's attention has been focused on the coronavirus crisis but Yemen, Bangladesh and many others countries in Asia and Africa are also in the grips of another pandemic: cholera. The current cholera pandemic first emerged in the 1970s and has devastated many communities in low-income countries. Each year, cholera is responsible for an estimated 1.3 million to 4 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths worldwide.

Immunologist Hiroshi Kiyono and his team at the University of Tokyo hope they can be part of the solution: They're making a cholera vaccine out of rice.

"It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot."

Cholera is caused by eating food or drinking water that's contaminated by the feces of a person infected with the cholera bacteria, Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria produces the cholera toxin in the intestines, leading to vomiting, diarrhea and severe dehydration. Cholera can kill within hours of infection if it if's not treated quickly.

Current cholera vaccines are mainly oral. The most common oral are given in two doses and are made out of animal or insect cells that are infected with killed or weakened cholera bacteria. Dukoral also includes cells infected with CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. Scientists grow cells containing the cholera bacteria and the CTB in bioreactors, large tanks in which conditions can be carefully controlled.

These cholera vaccines offer moderate protection but it wears off relatively quickly. Cold storage can also be an issue. The most common oral vaccines can be stored at room temperature but only for 14 days.

"Current vaccines confer around 60% efficacy over five years post-vaccination," says Lucy Breakwell, who leads the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's cholera work within Global Immunization Division. Given the limited protection, refrigeration issue, and the fact that current oral vaccines require two disease, delivery of cholera vaccines in a campaign or emergency setting can be challenging. "There is a need to develop and test new vaccines to improve public health response to cholera outbreaks."

A New Kind of Vaccine

Kiyono and scientists at Tokyo University are creating a new, plant-based cholera vaccine dubbed MucoRice-CTB. The researchers genetically modify rice so that it contains CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. The rice is crushed into a powder, mixed with saline solution and then drunk. The digestive tract is lined with mucosal membranes which contain the mucosal immune system. The mucosal immune system gets trained to recognize the cholera toxin as the rice passes through the intestines.

The cholera toxin has two main parts: the A subunit, which is harmful, and the B subunit, also known as CTB, which is nontoxic but allows the cholera bacteria to attach to gut cells. By inducing CTB-specific antibodies, "we might be able to block the binding of the vaccine toxin to gut cells, leading to the prevention of the toxin causing diarrhea," Kiyono says.

Kiyono studies the immune responses that occur at mucosal membranes across the body. He chose to focus on cholera because he wanted to replicate the way traditional vaccines work to get mucosal membranes in the digestive tract to produce an immune response. The difference is that his team is creating a food-based vaccine to induce this immune response. They are also solely focusing on getting the vaccine to induce antibodies for the cholera toxin. Since the cholera toxin is responsible for bacteria sticking to gut cells, the hope is that they can stop this process by producing antibodies for the cholera toxin. Current cholera vaccines target the cholera bacteria or both the bacteria and the toxin.

David Pascual, an expert in infectious diseases and immunology at the University of Florida, thinks that the MucoRice vaccine has huge promise. "I truly believe that the development of a food-based vaccine can be effective. CTB has a natural affinity for sampling cells in the gut to adhere, be processed, and then stimulate our immune system, he says. "In addition to vaccinating the gut, MucoRice has the potential to touch other mucosal surfaces in the mouth, which can help generate an immune response locally in the mouth and distally in the gut."

Cost Effectiveness

Kiyono says the MucoRice vaccine is much cheaper to produce than a traditional vaccine. Current vaccines need expensive bioreactors to grow cell cultures under very controlled, sterile conditions. This makes them expensive to manufacture, as different types of cell cultures need to be grown in separate buildings to avoid any chance of contamination. MucoRice doesn't require such an expensive manufacturing process because the rice plants themselves act as bioreactors.

The MucoRice vaccine also doesn't require the high cost of cold storage. It can be stored at room temperature for up to three years unlike traditional vaccines. "Plant-based vaccine development platforms present an exciting tool to reduce vaccine manufacturing costs, expand vaccine shelf life, and remove refrigeration requirements, all of which are factors that can limit vaccine supply and accessibility," Breakwell says.

Kathleen Hefferon, a microbiologist at Cornell University agrees. "It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot," she says. "The fact that it is made in rice means the vaccine can be stored for long periods on the shelf, without losing its activity."

A plant-based vaccine may even be able to address vaccine hesitancy, which has become a growing problem in recent years. Hefferon suggests that "using well-known food plants may serve to reduce the anxiety of some vaccine hesitant people."

Challenges of Plant Vaccines

Despite their advantages, no plant-based vaccines have been commercialized for human use. There are a number of reasons for this, ranging from the potential for too much variation in plants to the lack of facilities large enough to grow crops that comply with good manufacturing practices. Several plant vaccines for diseases like HIV and COVID-19 are in development, but they're still in early stages.

In developing the MucoRice vaccine, scientists at the University of Tokyo have tried to overcome some of the problems with plant vaccines. They've created a closed facility where they can grow rice plants directly in nutrient-rich water rather than soil. This ensures they can grow crops all year round in a space that satisfies regulations. There's also less chance for variation since the environment is tightly controlled.

Clinical Trials and Beyond

After successfully growing rice plants containing the vaccine, the team carried out their first clinical trial. It was completed early this year. Thirty participants received a placebo and 30 received the vaccine. They were all Japanese men between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. 60 percent produced antibodies against the cholera toxin with no side effects. It was a promising result. However, there are still some issues Kiyono's team need to address.

The vaccine may not provide enough protection on its own. The antigen in any vaccine is the substance it contains to induce an immune response. For the MucoRice vaccine, the antigen is not the cholera bacteria itself but the cholera toxin the bacteria produces.

"The development of the antigen in rice is innovative," says David Sack, a professor at John Hopkins University and expert in cholera vaccine development. "But antibodies against only the toxin have not been very protective. The major protective antigen is thought to be the LPS." LPS, or lipopolysaccharide, is a component of the outer wall of the cholera bacteria that plays an important role in eliciting an immune response.

The Japanese team is considering getting the rice to also express the O antigen, a core part of the LPS. Further investigation and clinical trials will look into improving the vaccine's efficacy.

Beyond cholera, Kiyono hopes that the vaccine platform could one day be used to make cost-effective vaccines for other pathogens, such as norovirus or coronavirus.

"We believe the MucoRice system may become a new generation of vaccine production, storage, and delivery system."