Scientists redesign bacteria to tackle the antibiotic resistance crisis

Probiotic bacteria can be engineered to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs by releasing chemicals that kill them.

In 1945, almost two decades after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, he warned that as antibiotics use grows, they may lose their efficiency. He was prescient—the first case of penicillin resistance was reported two years later. Back then, not many people paid attention to Fleming’s warning. After all, the “golden era” of the antibiotics age had just began. By the 1950s, three new antibiotics derived from soil bacteria — streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline — could cure infectious diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, meningitis and typhoid fever, among others.

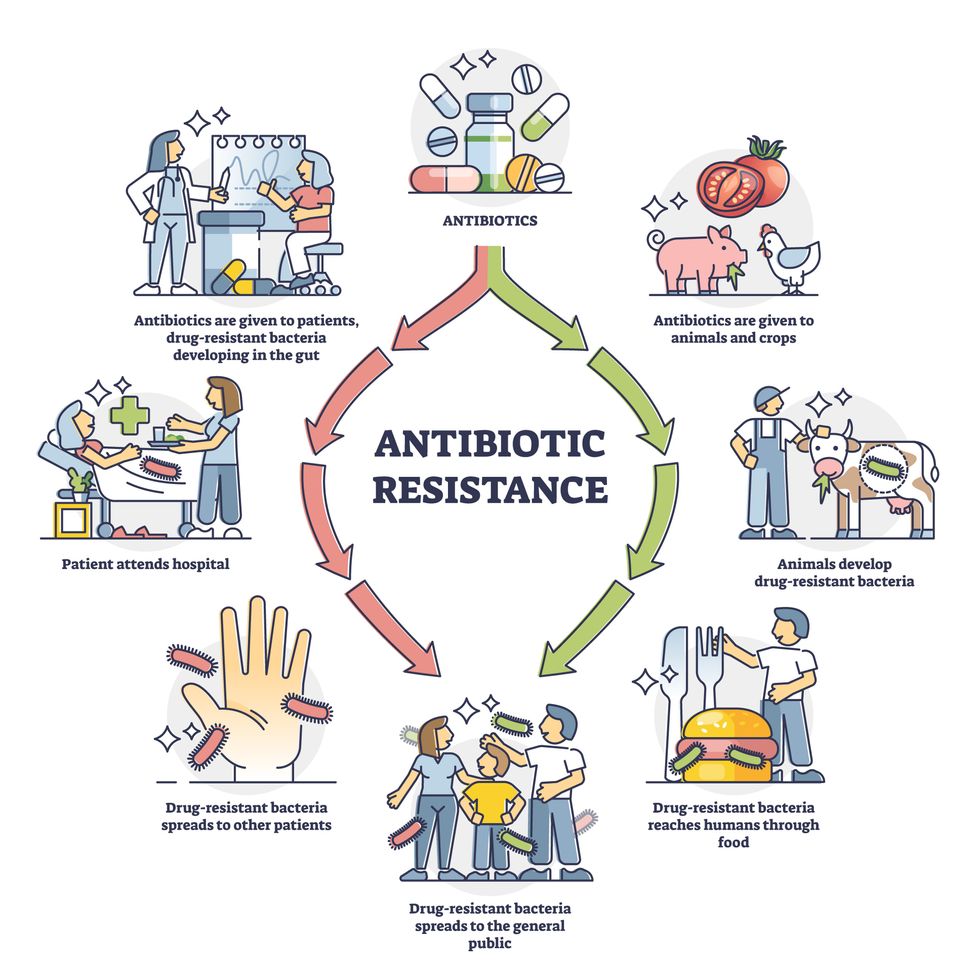

Today, these antibiotics and many of their successors developed through the 1980s are gradually losing their effectiveness. The extensive overuse and misuse of antibiotics led to the rise of drug resistance. The livestock sector buys around 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. every year. Farmers feed cows and chickens low doses of antibiotics to prevent infections and fatten up the animals, which eventually causes resistant bacterial strains to evolve. If manure from cattle is used on fields, the soil and vegetables can get contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Another major factor is doctors overprescribing antibiotics to humans, particularly in low-income countries. Between 2000 to 2018, the global rates of human antibiotic consumption shot up by 46 percent.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring a promising avenue: the use of synthetic biology to engineer new bacteria that may work better than antibiotics. The need continues to grow, as a Lancet study linked antibiotic resistance to over 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria. The western sub-Saharan Africa region had the highest death rate (27.3 people per 100,000).

Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

To make it worse, our remedy pipelines are drying up. Out of the 18 biggest pharmaceutical companies, 15 abandoned antibiotic development by 2013. According to the AMR Action Fund, venture capital has remained indifferent towards biotech start-ups developing new antibiotics. In 2019, at least two antibiotic start-ups filed for bankruptcy. As of December 2020, there were 43 new antibiotics in clinical development. But because they are based on previously known molecules, scientists say they are inadequate for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria. Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

The rise of synthetic biology

To circumvent this dire future, scientists have been working on alternative solutions using synthetic biology tools, meaning genetically modifying good bacteria to fight the bad ones.

From the time life evolved on earth around 3.8 billion years ago, bacteria have engaged in biological warfare. They constantly strategize new methods to combat each other by synthesizing toxic proteins that kill competition.

For example, Escherichia coli produces bacteriocins or toxins to kill other strains of E.coli that attempt to colonize the same habitat. Microbes like E.coli (which are not all pathogenic) are also naturally present in the human microbiome. The human microbiome harbors up to 100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells. The majority of them are beneficial organisms residing in the gut at different compositions.

The chemicals that these “good bacteria” produce do not pose any health risks to us, but can be toxic to other bacteria, particularly to human pathogens. For the last three decades, scientists have been manipulating bacteria’s biological warfare tactics to our collective advantage.

In the late 1990s, researchers drew inspiration from electrical and computing engineering principles that involve constructing digital circuits to control devices. In certain ways, every cell in living organisms works like a tiny computer. The cell receives messages in the form of biochemical molecules that cling on to its surface. Those messages get processed within the cells through a series of complex molecular interactions.

Synthetic biologists can harness these living cells’ information processing skills and use them to construct genetic circuits that perform specific instructions—for example, secrete a toxin that kills pathogenic bacteria. “Any synthetic genetic circuit is merely a piece of information that hangs around in the bacteria’s cytoplasm,” explains José Rubén Morones-Ramírez, a professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico. Then the ribosome, which synthesizes proteins in the cell, processes that new information, making the compounds scientists want bacteria to make. “The genetic circuit remains separated from the living cell’s DNA,” Morones-Ramírez explains. When the engineered bacteria replicates, the genetic circuit doesn’t become part of its genome.

Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut.

In 2000, Boston-based researchers constructed an E.coli with a genetic switch that toggled between turning genes on and off two. Later, they built some safety checks into their bacteria. “To prevent unintentional or deleterious consequences, in 2009, we built a safety switch in the engineered bacteria’s genetic circuit that gets triggered after it gets exposed to a pathogen," says James Collins, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and faculty member at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “After getting rid of the pathogen, the engineered bacteria is designed to switch off and leave the patient's body.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics causes resistant strains to evolve

Adobe Stock

Seek and destroy

As the field of synthetic biology developed, scientists began using engineered bacteria to tackle superbugs. They first focused on Vibrio cholerae, which in the 19th and 20th century caused cholera pandemics in India, China, the Middle East, Europe, and Americas. Like many other bacteria, V. cholerae communicate with each other via quorum sensing, a process in which the microorganisms release different signaling molecules, to convey messages to its brethren. Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut. When untreated, cholera has a mortality rate of 25 to 50 percent and outbreaks frequently occur in developing countries, especially during floods and droughts.

Sometimes, however, V. cholerae makes mistakes. In 2008, researchers at Cornell University observed that when quorum sensing V. cholerae accidentally released high concentrations of a signaling molecule called CAI-1, it had a counterproductive effect—the pathogen couldn’t colonize the gut.

So the group, led by John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering, developed a novel strategy to combat V. cholerae. They genetically engineered E.coli to eavesdrop on V. cholerae communication networks and equipped it with the ability to release the CAI-1 molecules. That interfered with V. cholerae progress. Two years later, the Cornell team showed that V. cholerae-infected mice treated with engineered E.coli had a 92 percent survival rate.

These findings inspired researchers to sic the good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi onto the drug-resistant ones.

Three years later in 2011, Singapore-based scientists engineered E.coli to detect and destroy Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an often drug-resistant pathogen that causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. Once the genetically engineered E.coli found its target through its quorum sensing molecules, it then released a peptide, that could eradicate 99 percent of P. aeruginosa cells in a test-tube experiment. The team outlined their work in a Molecular Systems Biology study.

“At the time, we knew that we were entering new, uncharted territory,” says lead author Matthew Chang, an associate professor and synthetic biologist at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the study. “To date, we are still in the process of trying to understand how long these microbes stay in our bodies and how they might continue to evolve.”

More teams followed the same path. In a 2013 study, MIT researchers also genetically engineered E.coli to detect P. aeruginosa via the pathogen’s quorum-sensing molecules. It then destroyed the pathogen by secreting a lab-made toxin.

Probiotics that fight

A year later in 2014, a Nature study found that the abundance of Ruminococcus obeum, a probiotic bacteria naturally occurring in the human microbiome, interrupts and reduces V.cholerae’s colonization— by detecting the pathogen’s quorum sensing molecules. The natural accumulation of R. obeum in Bangladeshi adults helped them recover from cholera despite living in an area with frequent outbreaks.

The findings from 2008 to 2014 inspired Collins and his team to delve into how good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi can attack drug-resistant bacteria. In 2018, Collins and his team developed the engineered probiotic strategy. They tweaked a bacteria commonly found in yogurt called Lactococcus lactis to treat cholera.

Engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut. --José Rubén Morones-Ramírez.

More scientists followed with more experiments. So far, researchers have engineered various probiotic organisms to fight pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (leading cause of skin, tissue, bone, joint and blood infections) and Clostridium perfringens (which causes watery diarrhea) in test-tube and animal experiments. In 2020, Russian scientists engineered a probiotic called Pichia pastoris to produce an enzyme called lysostaphin that eradicated S. aureus in vitro. Another 2020 study from China used an engineered probiotic bacteria Lactobacilli casei as a vaccine to prevent C. perfringens infection in rabbits.

In a study last year, Ramírez’s group at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, engineered E. coli to detect quorum-sensing molecules from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA, a notorious superbug. The E. coli then releases a bacteriocin that kills MRSA. “An antibiotic is just a molecule that is not intelligent,” says Ramírez. “On the other hand, engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut.”

Collins and Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, found that engineered E. coli can help treat other conditions—such as phenylketonuria, a rare metabolic disorder, that causes the build-up of an amino acid phenylalanine. Their start-up Synlogic aims to commercialize the technology, and has completed a phase 2 clinical trial.

Circumventing the challenges

The bacteria-engineering technique is not without pitfalls. One major challenge is that beneficial gut bacteria produce their own quorum-sensing molecules that can be similar to those that pathogens secrete. If an engineered bacteria’s biosensor is not specific enough, it will be ineffective.

Another concern is whether engineered bacteria might mutate after entering the gut. “As with any technology, there are risks where bad actors could have the capability to engineer a microbe to act quite nastily,” says Collins of MIT. But Collins and Ramírez both insist that the chances of the engineered bacteria mutating on its own are virtually non-existent. “It is extremely unlikely for the engineered bacteria to mutate,” Ramírez says. “Coaxing a living cell to do anything on command is immensely challenging. Usually, the greater risk is that the engineered bacteria entirely lose its functionality.”

However, the biggest challenge is bringing the curative bacteria to consumers. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in antibiotics or their alternatives because it’s less profitable than developing new medicines for non-infectious diseases. Unlike the more chronic conditions like diabetes or cancer that require long-term medications, infectious diseases are usually treated much quicker. Running clinical trials are expensive and antibiotic-alternatives aren’t lucrative enough.

“Unfortunately, new medications for antibiotic resistant infections have been pushed to the bottom of the field,” says Lu of MIT. “It's not because the technology does not work. This is more of a market issue. Because clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the only solution is that governments will need to fund them.” Lu stresses that societies must lobby to change how the modern healthcare industry works. “The whole world needs better treatments for antibiotic resistance.”

An implant, combined with the glasses and tiny video camera modeled in this photo, could improve the eyesight of millions of people with degenerative eye diseases in the coming years.

For millions of people with macular degeneration, treatment options are slim. The disease causes loss of central vision, which allows us to see straight ahead, and is highly dependent on age, with people over 75 at approximately 30% risk of developing the disorder. The BrightFocus Foundation estimates 11 million people in the U.S. currently have one of three forms of the disease.

Recently, ophthalmologists including Daniel Palanker at Stanford University published research showing advances in the PRIMA retinal implant, which could help people with advanced, age-related macular degeneration regain some of their sight. In a feasibility study, five patients had a pixelated chip implanted behind the retina, and three were able to see using their remaining peripheral vision and—thanks to the implant—their partially restored central vision at the same time.

Should people with macular degeneration be excited about these results?

“Every week, if not every day, patients come to me with this question because it's devastating when they lose their central vision,” says retinal surgeon Lynn Huang. About 40% of her patients have macular degeneration. Huang tells them that these implants, along with new medications and stem cell therapies, could be useful in the coming years.

“The goal here is to replace the missing photoreceptors with photovoltaic pixels, basically like little solar panels,” Palanker says.

That implant, a pixelated chip, works together with a tiny video camera on a specially designed pair of eyeglasses, which can be adjusted for each patient’s prescription. The video camera relays processed images to the chip, which electrically stimulates inner retinal neurons. These neurons, in turn, relay information to the brain’s visual cortex through the optic nerve. The chip restores patients’ central sight, but not completely. The artificial vision is basically monochromatic (whitish-yellowish) and fairly blurry; patients were still legally blind even after the implant, except when using a zoom function on the camera, but those with proper chip placement could make out large letters.

“The goal here is to replace the missing photoreceptors with photovoltaic pixels, basically like little solar panels,” Palanker says. These pixels, located on the implanted chip, convert light into pulsed electrical currents that stimulate retinal neurons. In time, Palanker hopes to improve the chips, resulting in bigger boosts to visual acuity.

The pixelated chips are surgically implanted during a process Palanker admits is still “a surgical learning curve.” In the study, three chips were implanted correctly, one was placed incorrectly, and another patient’s chip moved after the procedure; he did not follow post-surgical recommendations. One patient passed away during the study for unrelated reasons.

University of Maryland retinal specialist Kenneth Taubenslag, who was not involved in the study, said that subretinal surgeries have become less common in recent years, but expects implants to spur improvements in these techniques. “I think as people get more experience, [they’ll] probably get more reliable placement of the implant,” he said, pointing out that even the patient with the misplaced chip was able to gain some light perception, if not the same visual acuity as other patients.

Retinal implants have come under scrutiny lately. IEEE Spectrum reported that Second Sight, manufacturer of the Argus II implant used for people with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disease that causes vision loss, would no longer support the product. After selling hundreds of the implants at $150,000 apiece, company leaders announced they’d “decided to pursue an orderly wind down” of Second Sight in March 2020 in the wake of financial issues. Last month, the company announced a merger, shifting its focus to a new retinal implant, raising questions for patients who have Argus II implants.

Retinal surgeon Eugene de Juan of the University of California, San Francisco, was involved with early studies of the Argus implants, though his participation ended over a decade ago, before the device was marketed by Second Sight. He says he would consider recommending future implants to patients with macular degeneration, given the promise of the technology and the lack of other alternatives.

“I tell my patients that this is an area of active research and development, and it's getting better and better, so let's not give up hope,” de Juan says. He believes cautious optimism for Palanker’s implant is appropriate: “It's not the first, it's not the only, but it's a good approach with a good team.”

How dozens of men across Alaska (and their dogs) teamed up to save one town from a deadly outbreak

In 1925, health officials in Alaska came up with a creative solution to save a remote fishing town from a deadly disease outbreak.

During the winter of 1924, Curtis Welch – the only doctor in Nome, a remote fishing town in northwest Alaska – started noticing something strange. More and more, the children of Nome were coming to his office with sore throats.

Initially, Welch dismissed the cases as tonsillitis or some run-of-the-mill virus – but when more kids started getting sick, with some even dying, he grew alarmed. It wasn’t until early 1925, after a three-year-old boy died just two weeks after becoming ill, that Welch realized that his worst suspicions were true. The boy – and dozens of other children in town – were infected with diphtheria.

A DEADLY BACTERIA

Diphtheria is nearly nonexistent and almost unheard of in industrialized countries today. But less than a century ago, diphtheria was a household name – one that struck fear in the heart of every parent, as it was extremely contagious and particularly deadly for children.

Diphtheria – a bacterial infection – is an ugly disease. When it strikes, the bacteria eats away at the healthy tissues in a patient’s respiratory tract, leaving behind a thick, gray membrane of dead tissue that covers the patient's nose, throat, and tonsils. Not only does this membrane make it very difficult for the patient to breathe and swallow, but as the bacteria spreads through the bloodstream, it causes serious harm to the heart and kidneys. It sometimes also results in nerve damage and paralysis. Even with treatment, diphtheria kills around 10 percent of people it infects. Young children, as well as adults over the age of 60, are especially at risk.

Welch didn’t suspect diphtheria at first. He knew the illness was incredibly contagious and reasoned that many more people would be sick – specifically, the family members of the children who had died – if there truly was an outbreak. Nevertheless, the symptoms, along with the growing number of deaths, were unmistakable. By 1925 Welch knew for certain that diphtheria had come to Nome.

In desperation, Welch tried treating an infected seven-year-old girl with some expired antitoxin – but she died just a few hours after he administered it.

AN INACCESSIBLE CURE

A vaccine for diphtheria wouldn’t be widely available until the mid-1930s and early 1940s – so an outbreak of the disease meant that each of the 10,000 inhabitants of Nome were all at serious risk.

One option was to use something called an antitoxin – a serum consisting of anti-diphtheria antibodies – to treat the patients. However, the town’s reserve of diphtheria antitoxin had expired. Welch had ordered a replacement shipment of antitoxin the previous summer – but the shipping port that was set to deliver the serum had been closed due to ice, and no new antitoxin would arrive before spring of 1925. In desperation, Welch tried treating an infected seven-year-old girl with some expired antitoxin – but she died just a few hours after he administered it.

Welch radioed for help to all the major towns in Alaska as well as the US Public Health Service in Washington, DC. His telegram read: An outbreak of diphtheria is almost inevitable here. I am in urgent need of one million units of diphtheria antitoxin. Mail is the only form of transportation.

FOUR-LEGGED HEROES

When the Alaskan Board of Health learned about the outbreak, the men rushed to devise a plan to get antitoxin to Nome. Dropping the serum in by airplane was impossible, as the available planes were unsuitable for flying during Alaska’s severe winter weather, where temperatures were routinely as cold as -50 degrees Fahrenheit.

In late January 1925, roughly 30,000 units of antitoxin were located in an Anchorage hospital and immediately delivered by train to a nearby city, Nenana, en route to Nome. Nenana was the furthest city that was reachable by rail – but unfortunately it was still more than 600 miles outside of Nome, with no transportation to make the delivery. Meanwhile, Welch had confirmed 20 total cases of diphtheria, with dozens more at high risk. Diphtheria was known for wiping out entire communities, and the entire town of Nome was in danger of suffering the same fate.

It was Mark Summer, the Board of Health superintendent, who suggested something unorthodox: Using a relay team of sled-racing dogs to deliver the antitoxin serum from Nenana to Nome. The Board quickly voted to accept Summer’s idea and set up a plan: The thousands of units of antitoxin serum would be passed along from team to team at different towns along the mail route from Nenana to Nome. When it reached a town called Nulato, a famed dogsled racer named Leonhard Seppala and his experienced team of huskies would take the serum more than 90 miles over the ice of Norton Sound, the longest and most treacherous part of the journey. Past the sound, the serum would change hands several times more before arriving in Nome.

Between January 27 and 31, the serum passed through roughly a dozen drivers and their dog sled teams, each of them carrying the serum between 20 and 50 miles to the next destination. Though each leg of the trip took less than a day, the sub-zero temperatures – sometimes as low as -85 degrees – meant that every driver and dog risked their lives. When the first driver, Bill Shannon, arrived at his checkpoint in Tolovana on January 28th, his nose was black with frostbite, and three of his dogs had died. The driver who relieved Bill Shannon, named Edgar Kalland, needed the owner of a local roadhouse to pour hot water over his hands to free them from the sled’s metal handlebar. Two more dogs from another relay team died before the serum was passed to Seppala at a town called Ungalik.

THE FINAL STRETCHES

Seppala and his team raced across the ice of the Norton Sound in the dead of night on January 31, with wind chill temperatures nearing an astonishing -90 degrees. The team traveled 84 miles in a single day before stopping to rest – and once rested, they set off again in the middle of the night through a raging winter storm. The team made it across the ice, as well as a 5,000-foot ascent up Little McKinley Mountain, to pass the serum to another driver in record time. The serum was now just 78 miles from Nome, and the death toll in town had reached 28.

The serum reached Gunnar Kaasen and his team of dogs on February 1st. Balto, Kaasen’s lead dog, guided the team heroically through a winter storm that was so severe Kaasen later reported not being able to see the dogs that were just a few feet ahead of him.

Visibility was so poor, in fact, that Kaasen ran his sled two miles past the relay point before noticing – and not wanting to lose a minute, he decided to forge on ahead rather than doubling back to deliver the serum to another driver. As they continued through the storm, the hurricane-force winds ripped past Kaasen’s sled at one point and toppled the sled – and the serum – overboard. The cylinder containing the antitoxin was left buried in the snow – and Kaasen tore off his gloves and dug through the tundra to locate it. Though it resulted in a bad case of frostbite, Kaasen eventually found the cylinder and kept driving.

Kaasen arrived at the next relay point on February 2nd, hours ahead of schedule. When he got there, however, he found the relay driver of the next team asleep. Kaasen took a risk and decided not to wake him, fearing that time would be wasted with the next driver readying his team. Kaasen, Balto, and the rest of the team forged on, driving another 25 miles before finally reaching Nome just before six in the morning. Eyewitnesses described Kaasen pulling up to the town’s bank and stumbling to the front of the sled. There, he collapsed in exhaustion, telling onlookers that Balto was “a damn fine dog.”

A LIVING LEGACY

Just a few hours after Balto’s heroic arrival in Nome, the serum had been thawed and was ready to administer to the patients with diphtheria. Amazingly, the relay team managed to complete the entire journey in just 127 hours – a world record at the time – without one serum vial damaged or destroyed. The serum shipment that arrived by dogsled – along with additional serum deliveries that followed in the next several weeks – were successful in stopping the outbreak in its tracks.

Balto and several other dogs – including Togo, the lead dog on Seppala’s team – were celebrated as local heroes after the race. Balto died in 1933, while the last of the human serum runners died in 1999 – but their legacy lives on: In early 2021, an all-female team of healthcare workers made the news by braving the Alaskan winter to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to people in rural North Alaska, traveling by bobsled and snowmobile – a heroic journey, and one that would have been unthinkable had Balto, Togo, and the 1925 sled runners not first paved the way.